What Are the Best "Bad" Movies? A Statistical Analysis

The best of the "worst" movies ever made.

Intro: A Subpar Five-Star Masterpiece

This past weekend, I saw One Battle After Another, a buzzy prestige film that is indeed worth the hype (or at least 85% of the hype). As I went to log the movie on Letterboxd, I noticed something rather unfortunate among my last five reviews:

I awarded One Battle After Another—a virtuosic masterpiece and presumptive Best Picture winner—four and a half stars (out of five).

Two weeks earlier, I gave Scary Movie 3 a perfect five-star rating.

You can probably tell from context clues that Scary Movie 3 neither qualifies as a virtuosic masterpiece nor was it a Best Picture contender. There is, however, a running gag in this film where aliens urinate out of their index fingers.

My apologies to the film bros who’ve seen One Battle After Another four times and are pathologically compelled to describe their Blu-ray collection to strangers. That said, I stand by my five-star rating of a horror spoof sequel from the mid-2000s. Sure, some may write off Scary Movie 3 as “bad” or “dumb”—and they wouldn’t be wrong—but I love the film anyway. In fact, the stupidity heightens my enjoyment, which is why it was my favorite movie when I was 11 years old.

To consciously appreciate something “bad”—like an entry from the Scary Movie franchise—you have to hold two competing ideas in your mind. The first is that a film falls well short of cinematic greatness, sometimes intentionally but mostly by accident. The second is that the movie is eminently enjoyable, often as a result of these flaws. But not every lackluster film strikes the rare alchemical balance of being “so bad that it’s good.”

So today, we’ll explore the films that managed to achieve lasting cultural relevance, commercial success, and devoted fanbases—despite being widely dismissed as mediocre (or worse). We’ll then combine these criteria to create a definitive ranking of cinema’s best “bad” movies.

Bad Films with Lasting Cultural Relevance

Most subpar movies are either little-seen or widely panned before subsequently getting memory-holed. No one discusses the cultural implications of Yes Day and Ghosted, or whether Central Intelligence and The Internship reshaped commercial appetites. Odds are, you read that last sentence and were unsure whether those movies actually exist (like the film equivalent of “two truths and a lie”). Well, surprise—they’re all real and they’re all less-than-stellar.

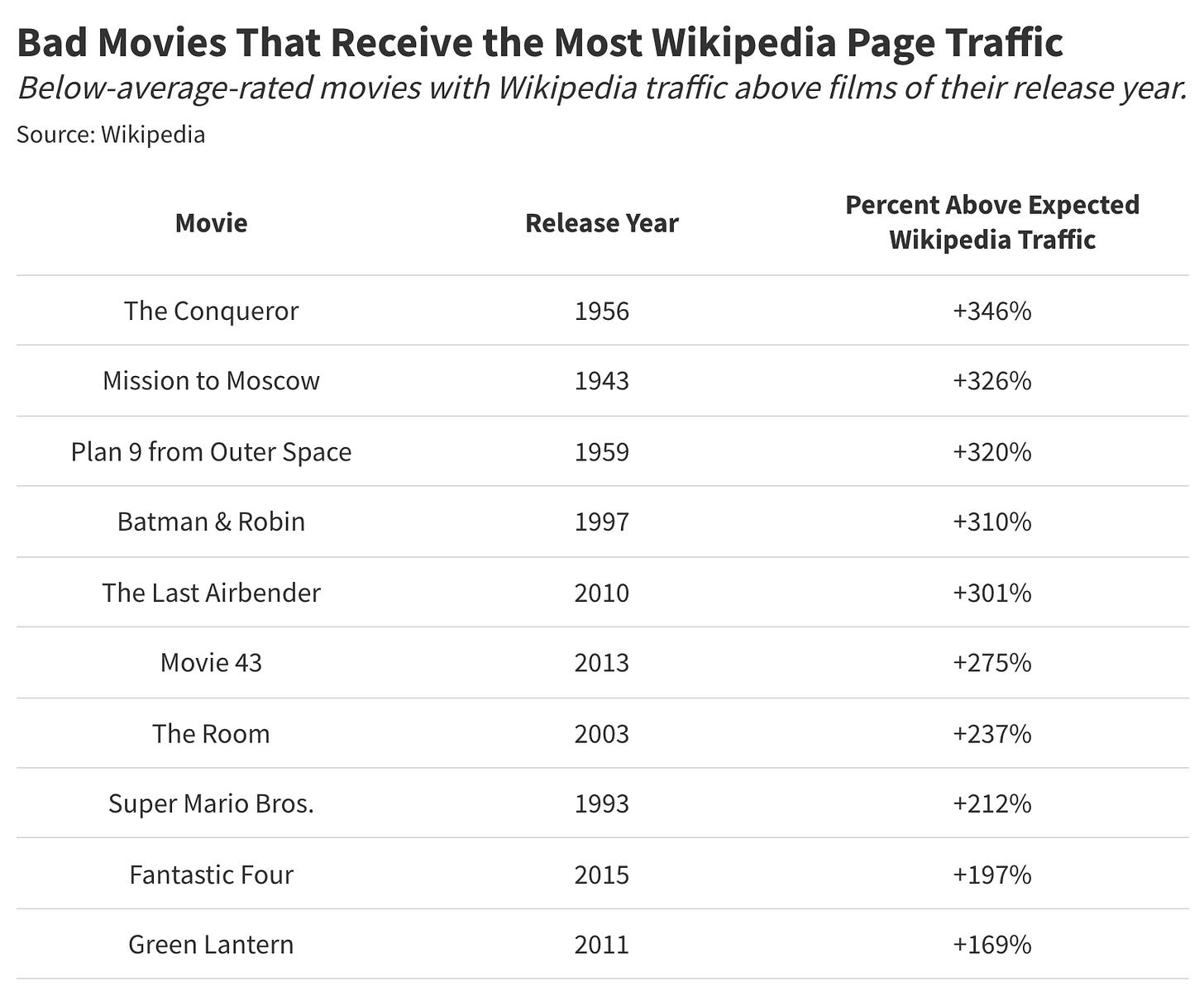

But occasionally, a second-rate film carries an outsized cultural footprint that far exceeds its artistic merit. To identify these titles, we’ll use two criteria:

Online ratings to identify poor quality: any movie with an average rating of less than 5 (out of 10) qualifies as “bad.”

Wikipedia page views as a marker of cultural endurance: we’ll compare a movie’s Wikipedia traffic to the average for films released the same year. For example, if 2016 Best Picture winner Moonlight is 250% above expected annual page views, then it’s searched significantly more than the average film from 2016.

Our resulting list of well-trafficked misfires is marked by historical oddities and films that are famously terrible.

Some observations:

Unfortunate historical events surrounding a movie: Mission to Moscow was an overtly pro-Soviet Hollywood film commissioned by the U.S. government during World War II, when the USSR was allied with the West. Needless to say, the film aged poorly—and many of those involved were later scrutinized by Congress during the Red Scare. The Conqueror was a 1956 historical epic in which white Western icon John Wayne plays Genghis Khan (seriously). The production took place downwind of an above-ground nuclear test site, which may or may not have caused 41% of the cast and crew to develop cancer later in life (a figure that qualifies as a statistical anomaly). These films are not good “bad” films so much as they are historically notable “bad” films.

“Worst movie of all time” contenders: The Room and Plan 9 from Outer Space are frequently canonized among the worst films of all time. Both movies were helmed by eccentric directors whose baffling creative decisions turned their movies into camp classics. Their legacies were further cemented by Hollywood biopics (The Disaster Artist and Ed Wood) that dramatize the production of these so-bad-they’re-good cult favorites.

Terrible Franchise Films: The 1993 Super Mario Bros. adaptation and 2015 Fantastic Four reboot were total train wrecks—films their studios would like erased from collective memory. Why? So they can sell you the same rebooted franchise a dozen more times (with slightly better quality). Sometimes, cultural amnesia is an asset—especially when you’re a movie studio that owns intellectual property.

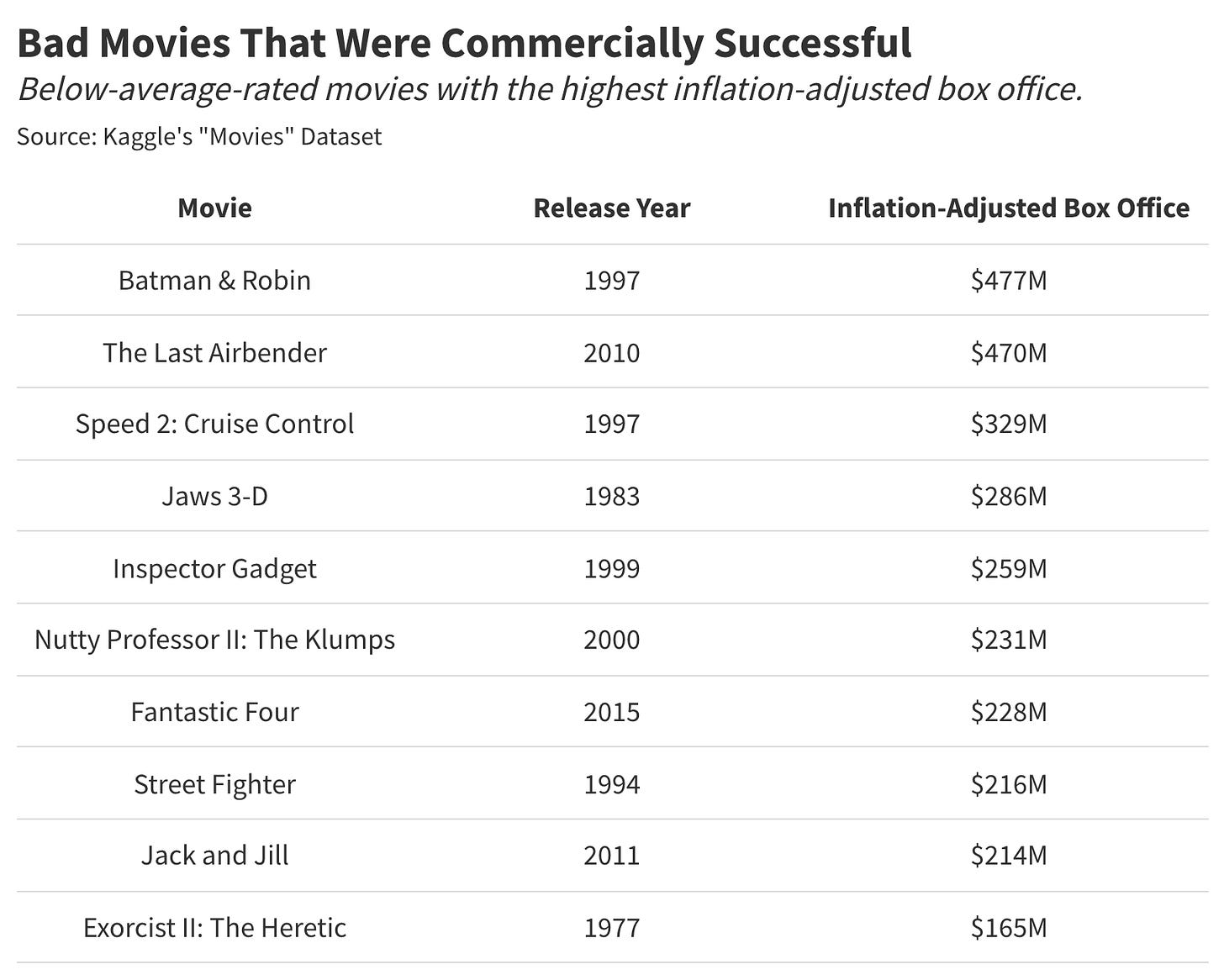

Bad Films That Made Money

My original plan was to include box office performance in our criteria—but after reviewing the data, I scrapped it. So what changed? As far as I can tell, audiences hated these movies upon release and in retrospect. No one on the internet is clamoring for a cultural reappraisal of 1999’s Inspector Gadget or Eddie Murphy’s Nutty Professor II: The Klumps.

So what’s the rationale for including films that don’t impact our final ranking? Two reasons:

The triviality of box office: Each of these movies is a reminder that financial performance does not guarantee cultural staying power. Bad films can make money in the short term, but that’s often where their legacy ends.

Comedic effect: This group is populated by silly movies that were produced, marketed, and consumed by thousands of adults. This list made me smile, and I hope you’ll smile too.

To identify poor-quality financial successes, I pulled the highest-grossing movies with an online rating below 5 (out of 10). The result is a graveyard of lucrative-yet-artistically-bankrupt stinkers.

Some observations:

Financial extortion via intellectual property (IP): Most of these movies are sequels or adaptations of existing IP. I am being willfully reductive when I say: audiences were tricked into seeing these films and were later frustrated by the exploitation of their fandom.

Jaws 3-D: This movie pitch reads like a ChatGPT hallucination, but alas, it’s real. In the summer of 1983, thousands of discerning consumers donned 3-D glasses to watch a shark get blown to smithereens (which they had already seen in earlier franchise installments, absent an extra visual dimension).

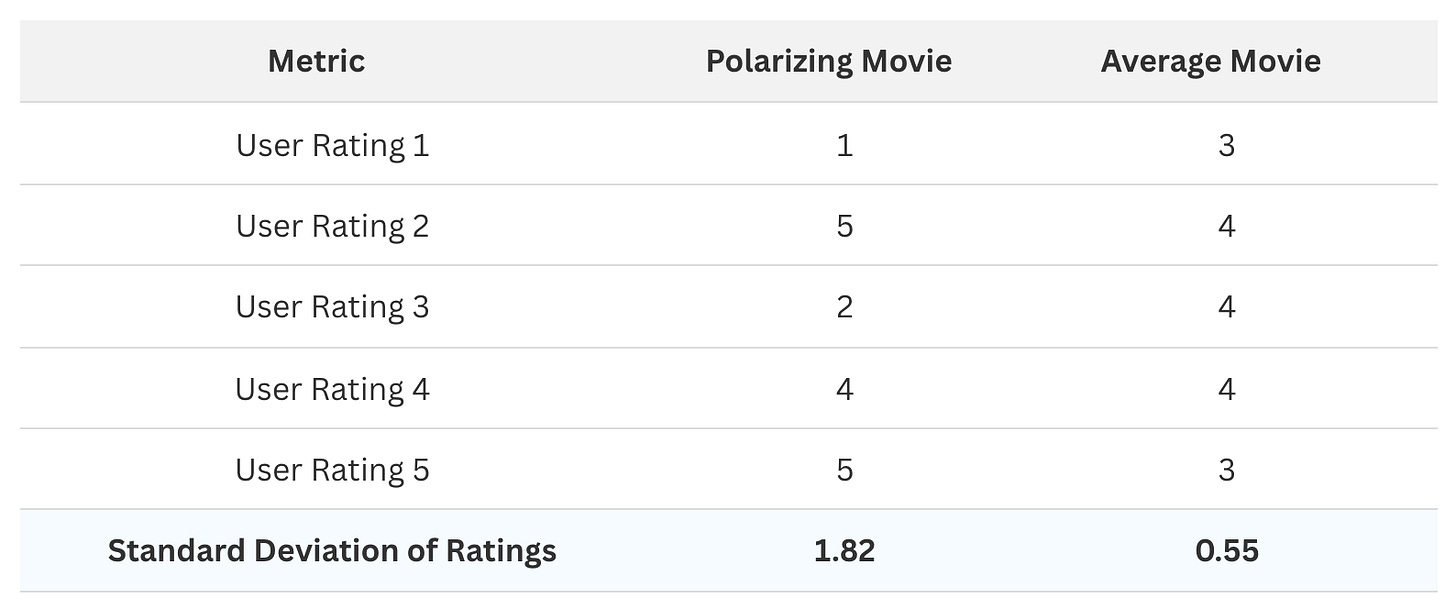

Bad Movies with Significant Online Fandoms

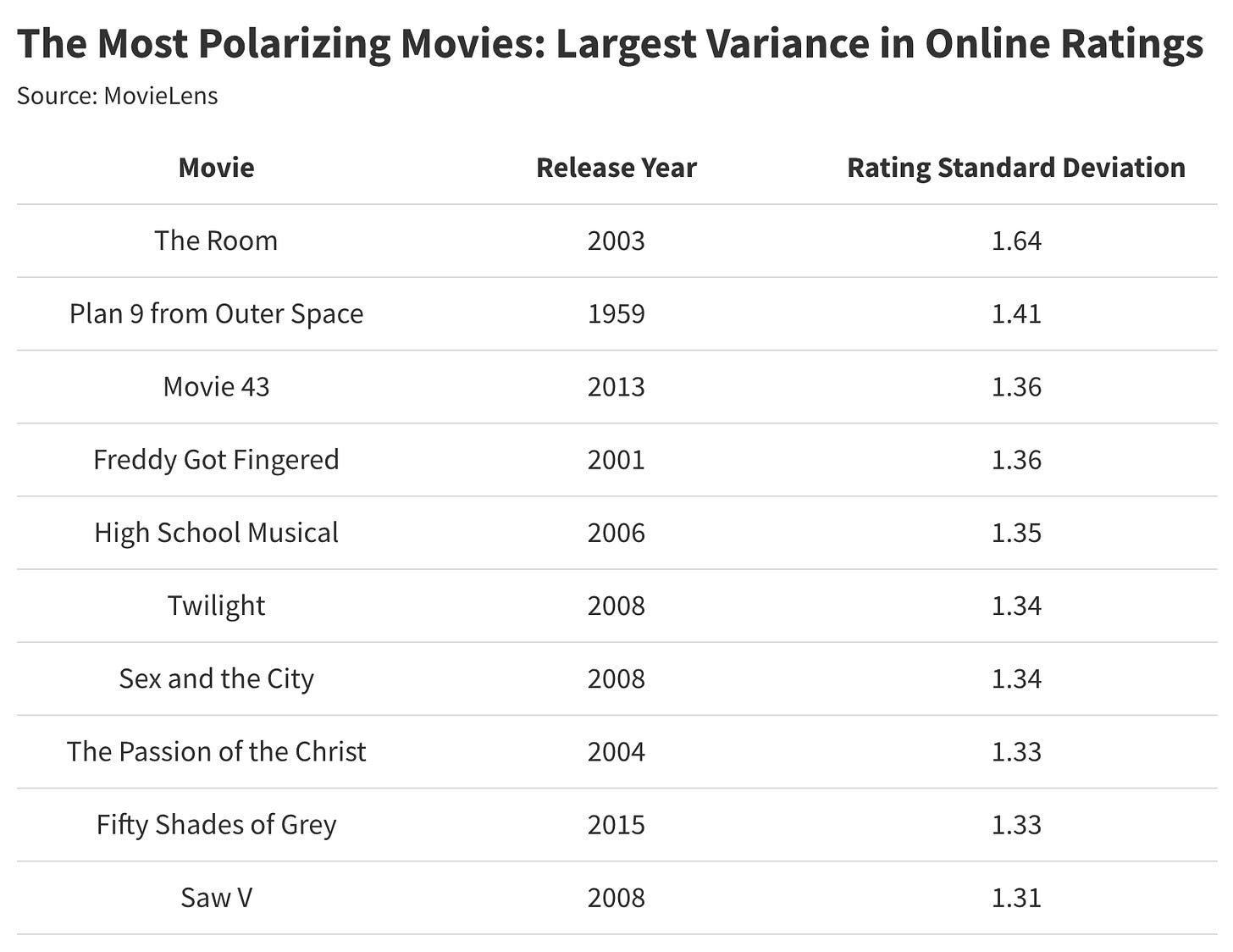

A film’s complex reputation is typically reflected in its online footprint. While some viewers dismiss a movie outright, others embrace it as a camp classic or mindless popcorn flick. This sentiment polarization is a hallmark of a beloved “bad” movie: a title is simultaneously adored and reviled. When opinions diverge, ratings tend to skew toward the extremes—fluctuating between one and five stars—whereas most film scores cluster within a narrower, more moderate range.

To quantify this divide, we’ll use the standard deviation of a film’s ratings as a proxy for critical disagreement. The calculation works like this:

The films with the greatest review variability fall into two groups: (1) celebrated camp classics and (2) blockbuster hits that triggered immediate backlash.

Some observations:

Many of these movies are made for teens and/or female audiences: Sometimes a film is so specifically targeted at a single demographic that its reception becomes bifurcated between its intended audience and those who were never meant to see it in the first place. High School Musical and Twilight spoke directly to teens, while Sex and the City and Fifty Shades of Grey were aimed at adult women. Movies don’t have to be made for everyone. I abstained from watching these films—and thus have no complaints about art that wasn’t meant for me.

Cult classics: The Room and Plan 9 from Outer Space are cult classics whose entire appeal hinges on how spectacularly bad they are. Which makes me wonder: how can anyone give these films a low star rating? You watch The Room precisely because it’s terrible—and if it delivers on this promise, that should qualify as a five-star experience. I don’t understand how someone could watch Plan 9 six decades after its release and still be shocked by its quality—though maybe I see things differently.

Gore: Saw V and The Passion of the Christ both feature graphic violence—and that’s where the similarities end. One movie is a sequel in a never-ending horror franchise that launched the “torture porn” subgenre; the other is a biblical epic that became one of the most commercially successful films of all time and kick-started an entire industry of faith-based cinema. And yet, I wasn’t allowed to see either movie when they came out—because of gore. This is, to the best of my knowledge, the first time these movies have appeared together in film theory discourse.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

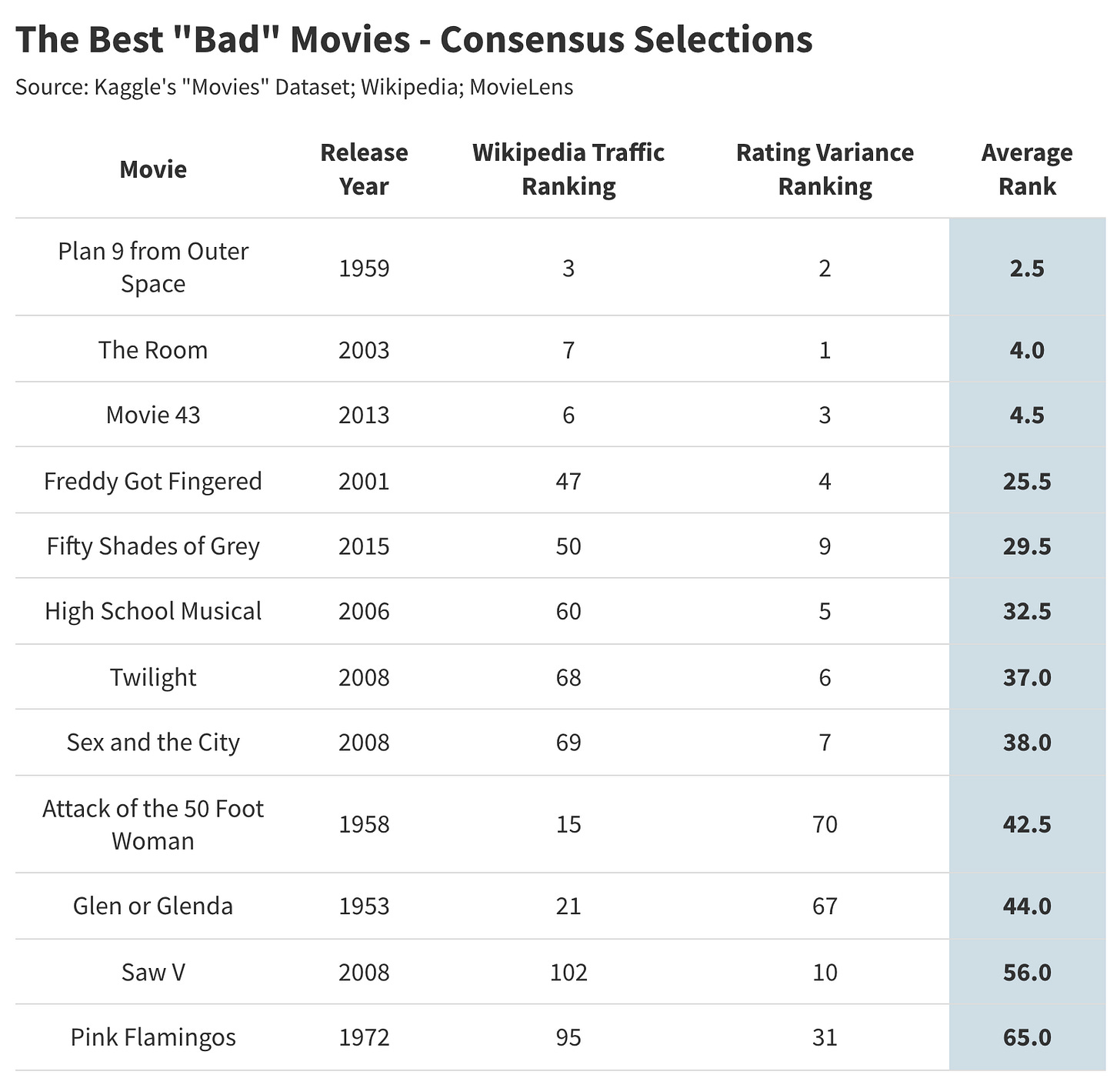

Our Final Ranking: The Best “Bad” Movies

For our final list, we’ll stack-rank films based on rating variance and Wikipedia traffic, and then average these respective rankings. As a reminder, we’ve excluded our commercial success criterion because these movies lack long-term cultural import (but are still fun to analyze).

Our final ranking favors a handful of “so-bad-they’re-good” cult classics and movies hyper-targeted at teens and female audiences.

Ed Wood—who is often dubbed “the worst director of all time”—lives up to his legend with Plan 9 from Outer Space and Glen or Glenda earning spots on our list. Tommy Wiseau, who easily qualifies as the weirdest director of all time, is similarly honored with the inclusion of his magnum opus, The Room. These men will be remembered for creating unforgettable dumpster fires—which, depending on your worldview, might be better than being forgotten.

Some titles that just missed the cut: Troll 2, Showgirls, Battlefield Earth, Batman & Robin, Gigli, and Cats.

Final Thoughts: A Window of Cultural Openness

A few years ago, I was on a Eurotrip with friends and did what any dumb American would do: I made everyone watch the 2004 raunchy comedy EuroTrip. As a kid, I loved this movie, and assumed it would somehow hold up—maybe even thrive—in this particular context. For one, EuroTrip features one of the greatest cameos in movie history: Matt Damon appears out of nowhere to lip-sync pop-punk anthem “Scotty Doesn’t Know.” The film is worth watching for this scene alone, which you can probably just find on YouTube.

Within ten minutes of starting the movie, I realized I’d made a terrible mistake. This film was aimed at American teenagers who’d never been to Europe and possessed a vague understanding of foreign cultures. The humor leans heavily on surface-level stereotypes: in the Netherlands, the punchline is “marijuana is legal, how silly!” and in England, the comedy revolves around “soccer hooligans being goofy!” Throw in a series of raunchy misadventures, and that’s pretty much the entire movie. Needless to say, the film does not resonate with Americans who are earnestly engaging with European culture.

To this day, my friends remind me of “the time I made them watch that dumb movie” while on vacation. But here’s the thing: I have no regrets. Better yet, I still think EuroTrip is hilarious—warts and all—similar to my love of Scary Movie 3. I have no shame.

Of course, the common thread between these movies—and other supposedly “bad” films I enjoy—is that I consumed them before reaching adulthood. In fact, nearly all of my debatably dumb pleasures—e.g., fantasy sports, Diners Drive-ins & Dives, collecting DVDs, Coldplay, McNuggets, and Forrest Gump—entered my life before I turned 18.

This realization raises an existentially vexing question: when did I stop enjoying “stupid” things? For those who take pride in their cultural appetites, disliking a poorly made movie is a non-issue: why would anyone appreciate inferior art? But in practice, it drastically shrinks the pool of watchable content. Now, everything I consume has to mean something. A movie must possess a Metacritic score above 70, and ideally some broader cultural relevance to justify two hours of my time, because those are the rules I’ve imposed upon myself. Somewhere along the way, my relationship to art changed.

This shift in movie-watching habits reminds me of an earlier analysis where I investigated when people stop finding new music. According to that research, a person’s “open-earedness” begins to wane in their early twenties, reducing their receptiveness to unfamiliar music styles. Prior to this point, listeners (and perhaps moviegoers) are less resistant to novelty. A thirteen-year-old doesn’t demand artistic brilliance from their music or movies; they simply absorb what’s put in front of them. That’s how Scary Movie 3 and EuroTrip made it into my personal canon. They arrived during a window of cultural openness—and despite their unmistakable stupidity, I’ll always have a soft spot for them.

Enjoying movies like Twilight, The Room, or Plan 9 from Outer Space requires holding two ideas at once: that something can be both “bad” and deeply enjoyable. Perhaps my issue is that I’ve become single-minded: only capable of appreciating virtuosic masterpieces like One Battle After Another and telling strangers about my Blu-ray collection.

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Have a publication or data product you’d like to advertise in Stat Significant? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

The NY Times is running an occasional series on "good bad" movies, with Patrick Swayze's Road House considered by those writing the series as the "best bad" movie in their opinions.

my favorite bad movie is sex and the city. so glad to see it get its bad movie flowers