Why I Started Renting DVDs Again: Quantifying a Silly Thing

Assessing my new fondness for renting DVDs, both the good and the bad.

Intro: Wait, Why?

Late last year, I began collecting DVDs. My rationale was simple: Movies have been a big part of my life, and I want to own the things I love in material form. Friends and family were sympathetic to this new hobby, with reactions like:

"Oh cool, so you're collecting them kinda like vinyl records?"

"I get that—wanting to own your favorite things."

"Owning The Dark Knight in 4k must be fun."

But as I began frequenting a local video store to build out my collection, a funny thing happened: I started renting DVDs. And then an even stranger thing happened: I developed a fondness for renting DVDs.

When I told friends and family of this new habit, their reactions were less generous:

"Wait, why?"

"Okay."

[prolonged silent confusion]

Indeed, this newfound ritual is mystifying, even to me. Renting physical media brings me great joy, but I know this practice is quantifiably foolish. As such, this new routine has led to profound introspection. Why am I doing this? What are the costs of this outdated practice, and what benefits make these drawbacks worthwhile? Am I becoming a Luddite?

So today, we'll explore the fall of video stores, gauge the downsides of renting physical media, and attempt to quantify the strangely wonderous upsides that have endeared me to this near-extinct form of commerce.

The Fall of Physical Media and Downsides of Renting

At their zenith, there was roughly one movie store for every 9,000 people in the United States—close to an average of one shop in every local jurisdiction. These stores served as the central nervous system for local film culture, providing a physical locale for cinephiles to discuss movies. These shops bred a generation of movie lovers, with several high-profile directors from the 1990s emerging as part of the "video store generation," including Quentin Tarantino, Kevin Smith, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Richard Linklater.

In 1997, Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph launched Netflix, shipping DVDs by mail and later pioneering streaming television. With Netflix, you could consume your favorite content without ever leaving the house. Fast forward to the present day—video stores are almost extinct, relics from an era when physical limitations moderated media consumption.

It's tempting to wax poetic about the loss of local movie hubs, to rue the rise of Netflix and binge culture, but this shift is not without reason. For one thing, streaming subscriptions and digital rentals offer a more affordable home entertainment solution than renting physical media.

While movies are my go-to form of media, I still enjoy high-quality prestige television (I'm only human), and thus, I pay for streaming channels in addition to my rental habit. Economists often speak of a theoretical consumer named Homo economicus—a hypothetical patron who makes the single-most rational decision with the information at their disposal. I can assure you that I am not Homo economicus. I have not picked the path of utmost rationality.

DVD rentership comes with a host of costs that may read as wildly anachronistic to older folks and downright alien to younger generations:

Per disc rental fees

Late fees

Buying a 4k region-free DVD player

Driving to and from the video store

When we factor in these additional expenses, the cost of renting physical media (while still paying for streaming channels) is significantly higher than the cost of consuming those same movies through a combination of streaming subscriptions and digital rentals.

The argument for renting physical media would be more appealing if I swore off streaming, which is something I do not intend to do.

But wait, there’s more. The downsides of renting go beyond cost, as the realities of physical inventory limit title selection. Those raised in the age of Blockbuster may recall that movie stores often didn't have the film you were looking for. Someone may be late on a return, or the shop doesn't carry that DVD, and all of a sudden you're changing your Friday night movie plans. Pretty wild, I know.

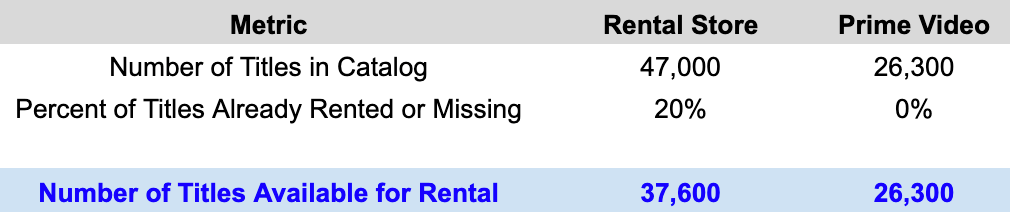

Amazon's Prime Video has over 26,300 movies available for renting and streaming. Compare this to my video store, which claims to have a library of over 47,000 titles. If we assume 20% of these DVDs are checked out or were never returned, then my local shop wins on title selection.

But not so fast. These numbers only speak to selection breadth, not availability. In fact, the movie I'm looking for is unavailable around 33% of the time—a figure that must be incomprehensible to anyone from Gen Z. Oftentimes, a delinquent renter simply never returned the disc, which means it will be out of stock for the foreseeable future. Therefore, several times a year, the friendly store clerk has the unfortunate task of informing me, "We don't have that title in stock right now."

This isn't the end of the world; I typically just select a new movie. At the same time, content scarcity is a societal ill long-eradicated by the likes of Hulu, YouTube, and Peacock. It's bizarre to embrace the finite, to willingly incur problems already solved by Silicon Valley's finest. Still, to me, it's worth it. Ultimately, it's the material nature of the renting experience that draws me to this ritual, for better or worse.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

The Wonderful Upsides of Renting Physical Media

Many hobbies facilitate social interaction and community. Cyclists bike in flocks, music lovers attend festivals, and football fans have sports bars and fantasy leagues. These pursuits can be tied to a place or group of like-minded individuals.

Films have movie theaters, but the act of moviegoing offers little chance for social interaction. You buy your tickets, sit in the dark alongside strangers, and then you depart. Afterward, you may chat about the movie with a friend, or maybe you just walk off silently into the night. In short, movies lack a physical place for community. In recent years, Letterboxd has attempted to fill this void by providing a social network for cinephiles. I love Letterboxd—it's an invaluable tool for film discovery—but virtual connection can only go so far.

And then there are the broader realities of an increasingly digitized world:

An estimated 22% of full-time employees will work from home by 2025.

According to government survey data, weekly time spent alone has increased by 20% over the last decade.

Every day, the typical human spends 6 hours and 37 minutes looking at a screen.

With each passing year, the average person becomes a bit more isolated— though we get to watch Squid Game, Love is Blind, and Mr. Beast, so it's not all bad.

Ted Gioia recently wrote a great piece on breaking free of "the dopamine cycle," replacing screen time and cheap dopamine hits with lived experience and discomfort. By happy accident, renting DVDs has enriched my week with a new outlet for non-screen human experience—adding a touch of novelty to Zoom-laden workdays.

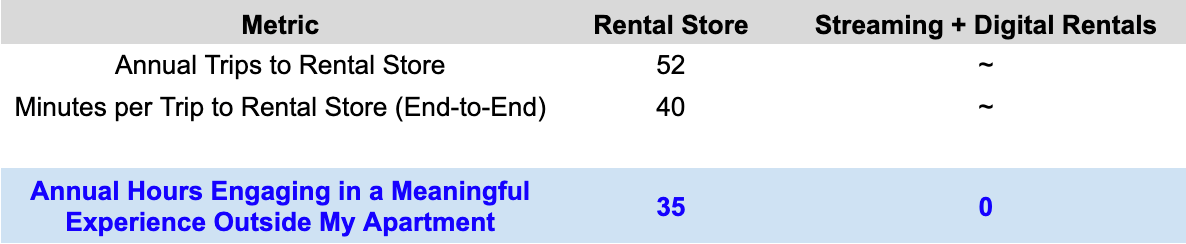

My average movie-renting pilgrimage takes around 40 minutes, end-to-end, totaling ~35 hours a year spent acquiring movies and chatting with film nerds. For me, this is a wonderful use of time.

And then there are the people at the store and the wonderfully nerdy conversations that spring from near-religious movie fandom. There is the friendly store clerk and a litany of folks who hang around the checkout counter (I have no idea if they work there, but they certainly elevate the store's ambiance). We'll typically talk about my movie selections, the directors and actors behind these pictures, and then brainstorm works related to these films. Over the course of a year, these brief chats add up to ~12 hours of in-depth conversation about my favorite thing with strangers who share this love.

Typically, this level of fandom or geekdom is reserved for Reddit message boards and Discord servers—virtual town squares where anonymous usernames bond over popular culture. Still, nothing beats a good old-fashioned in-person conversation about "whether Christopher Nolan sucks" (he doesn't), "whether Slumdog Millionaire is a good movie" (it is), or "Killers of The Flower Moon is too long" (it was).

What began as a social experiment became a weekly routine, and (as of now) I have no plans of stopping, despite its various inconveniences.

Final Thoughts: The Wonders of Friction

Recently, I subjected myself to a thought experiment: Would I enjoy my renting habit if I did so from a machine? Would I find this pursuit fulfilling if I walked over to a Redbox kiosk at a nearby grocery store, didn't talk to anyone, rented a few DVDs, and then walked home? The answer is no. When it comes to DVD renting, it's the ritual, not the end product, that I enjoy.

I do not believe:

That streaming will someday disappear, and that movie stores are primed for a major comeback.

That DVDs, Blu-rays, and 4k discs provide noticeable quality benefits (that matter to me).

That my writing on this topic should be interpreted as a virtue-signaling exercise about supporting local businesses. I have acquired a large portion of my DVD collection from Amazon and eBay, so it's hard for me to be authentically self-righteous on this point.

That DVD rentals offer a superior mode of content delivery (compared to streaming).

This new routine simply made sense for me, embracing friction in return for a sense of film community. Ultimately, I view my newfound renting ritual as a break from complacency, avoiding the creature comforts of technological progress in an effort to garner new experiences—even if it's just a passing conversation about Denis Villeneuve's filmography and the awesomeness of Dune 2. Perhaps there's some universal lesson here about rejecting ease in pursuit of connection, or maybe this is just a one-off case of a film nerd becoming a bit nerdier—perhaps it's a bit of both.

So much of my life is built around efficiency—streamlining my day-to-day in order to save the most money and time—it's nice to do something against my better judgment. With each DVD rental and its myriad inconveniences, I stray further from Homo economicus, pursuing something irrational, purposeful, and decidedly human.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

I rent most of my physical movies from the public library. They have a great selection and high availability. I started this during my undergraduate where the the university library had a great movie selection. This is a tangible moment of gratitude for your tax dollars serving you and your community.

Great article. I was thinking this morning about how the last four years felt like a detour. Things big and small, personal and systemic —relationships, workplaces and livelihoods — were broken and then rebuilt. It feels like a lot of society is finally shifting away from healing from the way life was upended during the pandemic and back to moving forward on the natural path and progression of life. Back on track from the detour. In a lot of ways — maybe the fact that it’s an election year is playing into it — this year feels like what 2020 was supposed to be. My hope is that part of this shift is people becoming less polarized and outraged, less online, the way things were when there was a Blockbuster down the street from my childhood home.

When reading the sentence referring to Reddit and Discord as “virtual town squares,” I couldn’t help but think of Twitter. I believe Elon Musk used that phrasing to describe Twitter around the time he bought it. Twitter might still be a bigger town, but Substack feels more like a town I want to live in, given its seemingly higher proportion of productive dialogue. But still, as you have found in the video stores, even the best virtual town squares pale in comparison to face-to-face interaction. It was great to read that real town squares such as your video store still exist. Hopefully, places like that are among the things we’ll go back valuing now that we’re back from the detour.