The Rise, Fall, and (Slight) Rise of DVDs. A Statistical Analysis

The death and second life of physical media.

Intro: The Death of Physical Media

The past year has been a disastrous one for physical media and a confusing one for me personally, marked by a series of ominous milestones:

DVD Sales Decline for the Sixteenth Straight Year: In the first half of 2023, physical media sales in the U.S. decreased to $754 million, down from $1.05 billion during the same period in 2022.

Netflix Ends its DVD Rental Service: On September 29, 2023, Netflix mailed its final DVD, marking an end to its 25 years of physical media renting.

Best Buy Ends DVD Sales: In October of 2023, Best Buy announced that it was discontinuing DVD and Blu-ray sales both in-store and online starting in early 2024.

I Decide to Start Collecting DVDs: In November of this year, I informed my wife that I wanted to begin collecting DVDs, to which she responded, "Why?"

There was once a time when people would buy movies twice, once at theaters and a second time for home viewing. Consumers could own their favorite films, and studios made tons of money servicing this demand. But over the past twenty years, physical media has declined to near-extinction as streaming evolved into the predominant mode of home entertainment.

And yet, recently, DVDs have experienced a minor revival, less as an enduring consumer good and more as a symbol of self-expression. If that sounds hokey or illogical, it's because it is. People (myself included) have chosen to forego convenience and economic practicality in order to fulfill an emotional desire, and so far, I am loving it.

So today, we'll explore the rise and fall of physical media, the changing economics of movie ownership, and the minor resurgence of a dying technology.

The Rise and Fall of Physical Media

Fifty years ago, you couldn't watch movies at home (apart from whatever played on cable television). Let's say you actively wanted to see Citizen Kane or take in Alfred Hitchcock's entire filmography; well, you couldn't. You'd accept the ephemeral nature of movie consumption and think, "I guess I may never see my favorite film again; what a bummer."

The late 1970s saw the introduction of VHS, giving way to a fledgling home entertainment industry that empowered consumers to choose and own their favorite content.

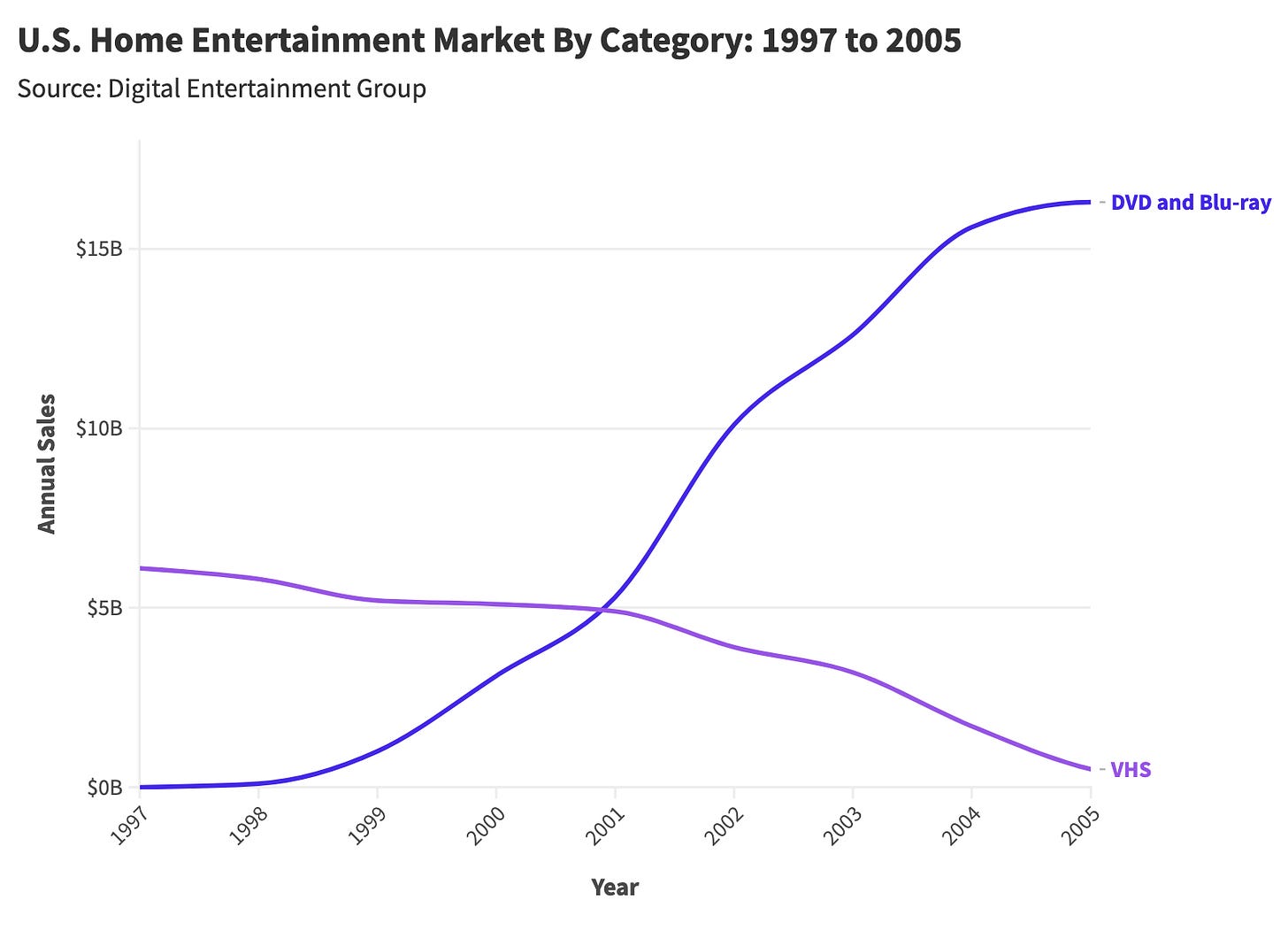

The late 1990s brought DVDs, which offered higher video quality and interactive features. Discs swiftly overtook videotape as the go-to format for home entertainment, with DVD sales peaking at $16 billion in 2005.

Physical media was a cash cow for movie studios, who could sell the same film to the same consumer multiple times. Let's say you loved The Lion King in a world before streaming, and you also wanted your children to be able to watch The Lion King. You may be giving Disney money for a movie ticket, a VHS purchase, a DVD purchase, and a Blu-ray purchase. That's at least $50 of Lion King spending.

Many films enjoyed active second lives on DVD and VHS, with popular titles bringing in over $500M of revenue for Hollywood studios (and this figure isn't even inflation-adjusted).

If these numbers seem too good to be true, it's because they were.

In January of 2007, Netflix launched its streaming service, providing consumers with an expansive selection of film and TV programming with virtually no friction. Movie watching was no longer bound by physical constraints, and a treasure trove of content was yours for a measly $5 a month. DVD sales plummeted as streaming subscriptions, digital rentals, and digital purchases grew to a combined ~$35B in annual sales.

Consumers didn't have to settle for video rental stores or cable re-runs of Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives; consumers could watch something remarkable whenever they pleased. Thus began the era of Peak TV, as numerous streaming platforms entered the market while content production and consumption increased exponentially.

Suddenly, the idea of owning your favorite films became impractical. Let's say I want to buy every movie from my Letterboxd list of 100 all-time favorites: I can buy these titles in physical format, or I can rent and stream them whenever I want. Assuming I watch each of these films two more times before I die, it will cost me significantly more to build a DVD collection while also taking up a non-trivial amount of space in my apartment.

To collect DVDs is to embark upon a path of financial inconvenience. The economic reality is that streaming is cheaper, provides greater selection, and offers minimal friction—it is the superior format for most consumers.

The discontinuation of Best Buy and Netflix's DVD programs was broadly seen as a death knell for physical media. Slate lamented, "The Death of Netflix DVD Marks the Loss of Something Even Bigger," and The Hollywood reporter wrote a eulogy for the era of physical media. And just like that, DVDs were an anachronism, a tool rendered wholly unfashionable by technological progress, much like 8-tracks, BlackBerrys, floppy disks, and pagers.

And yet, physical media lives. While the retail demand for movie collecting has diminished, DVDs still prosper in a smaller, niche secondary market, much like stamps, coins, and baseball cards.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

The Second Life of DVDs

The past three years have been tough for movie enthusiasts. Moviegoing suffered greatly during the pandemic and has been slow to recover. Stories previously produced for the big screen are more likely to be adapted into eight-episode series. Content is unlimited, yet these cultural products have no physical manifestation, floating around within the streaming ether. In short, it's been a weird time for the movies.

In response, cinephiles have flocked to the internet and looked to the past. Letterboxd, a social network for cinema nerds, offered film lovers a digital community for sharing and cataloging works, delivering an at-home substitute for the social experience of moviegoing. At the same time, many film nerds seemingly rejected the ubiquity and amorphousness of streaming, favoring the tangible ownership of DVD collecting.

In recent years, online communities centered on physical media have experienced substantial membership growth, with Reddit groups dedicated to DVD ownership gaining hundreds of thousands of new members.

These communities allow hobbyists to connect over a passion outside the mainstream, offering tips for finding and purchasing titles, as well as a forum for showcasing DVD collections.

The collapse of DVD sales channels has rendered physical media a collector's pursuit. Online searches featuring "DVD for Sale" spiked in mid-October after Best Buy and Netflix disowned their physical media operations, as purchasers began scouring the internet for other markets.

eBay, the world’s largest platform for trading memorabilia, has significantly benefited from retail's abandonment of physical media. A recent report from Self on "The Best Items to Sell on eBay in 2023" found DVD and Blu-ray to be the third-highest selling category on the site.

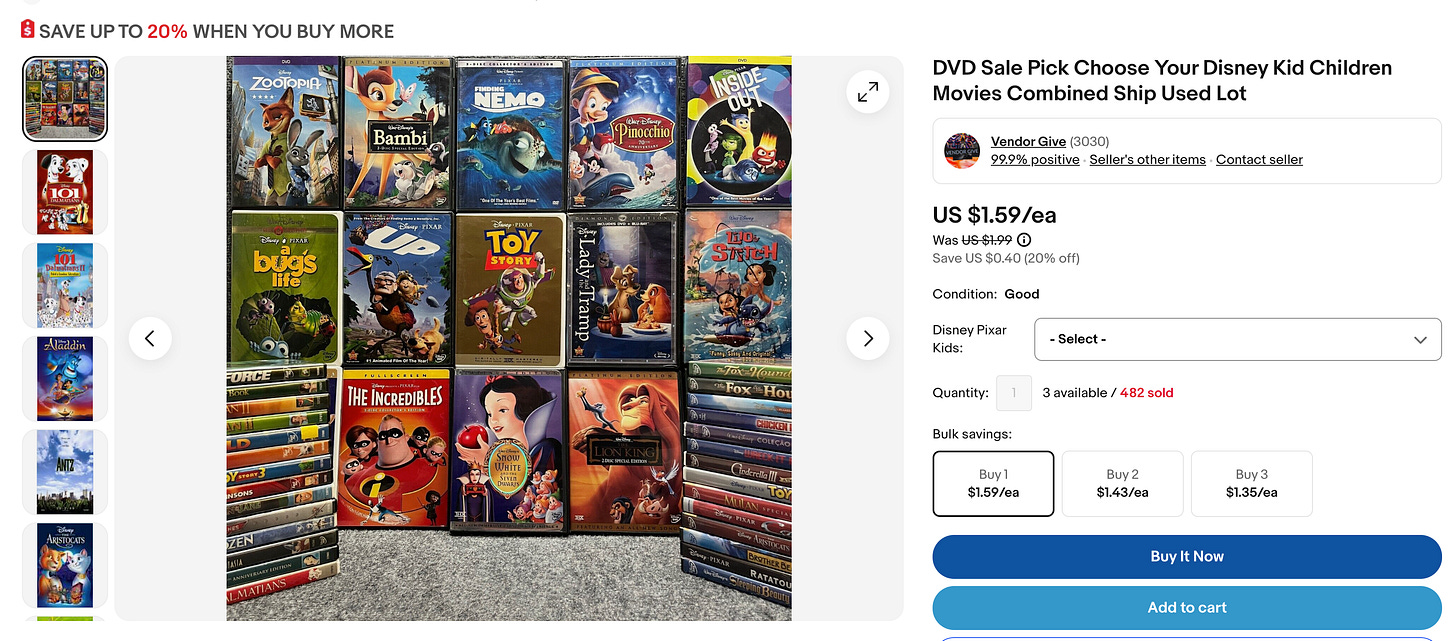

eBay's DVD listings constitute a bizarre market bifurcated into two distinctive product offerings. One listing type features sellers indiscriminately offloading boxfuls of Blu-rays for less than $2 a disc.

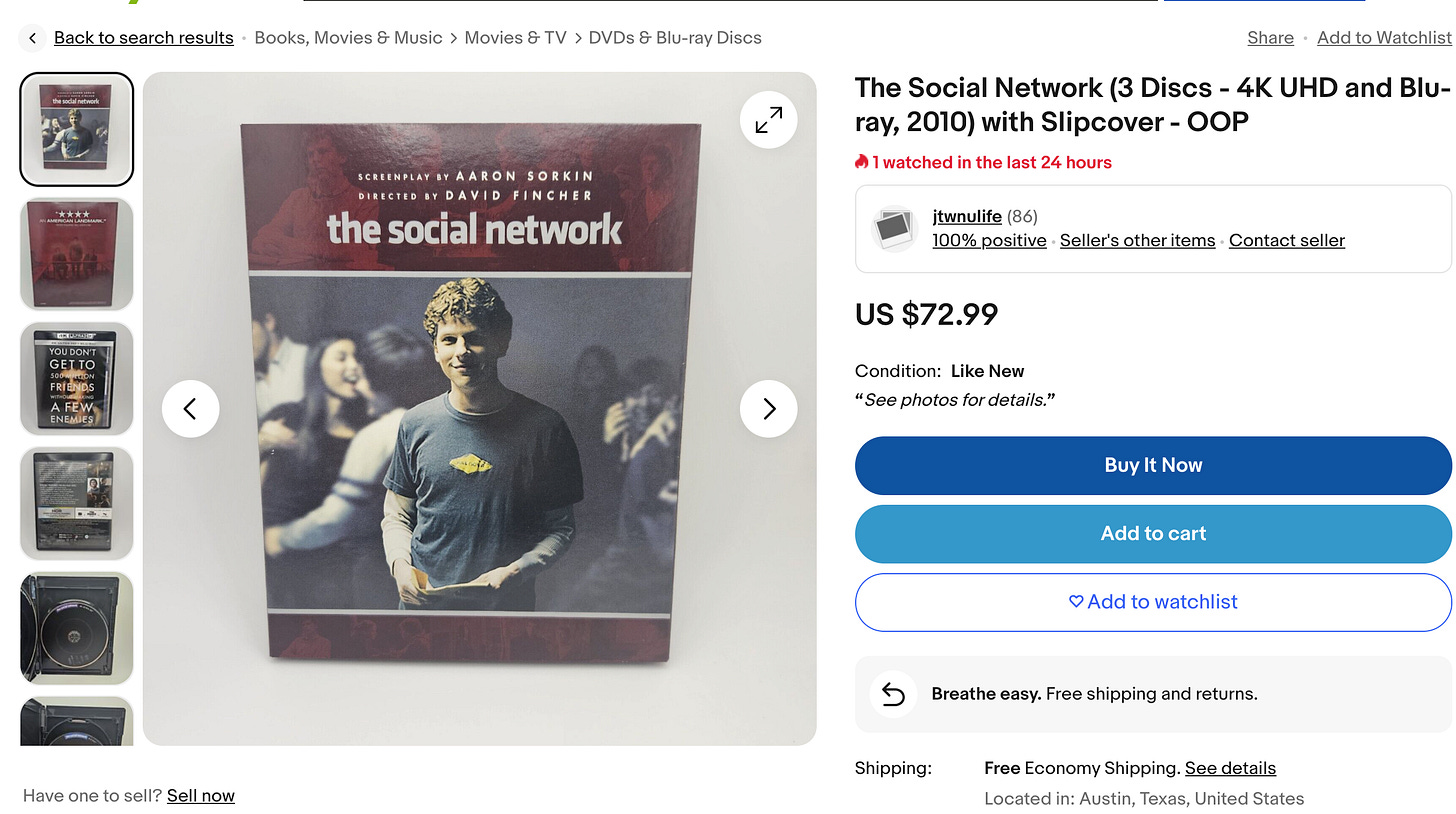

On the other end of the spectrum is an upscale market for collectors interested in high-quality cases (slipcovers, beautiful artwork, steel casing, etc.) of movies mastered in 4k, like this copy of The Social Network, which I really want to buy.

Unfortunately, this collectible is priced at $73(!!!), which is equivalent to around 5.5 Chipotle burritos, and is, therefore, too much to spend on a dying media format (or is it?).

Herein lies the perpetual dilemma of this absurd hobby. On the one hand, I want to own this aesthetically-pleasing physical representation of my all-time favorite movie. On the other hand, I could rent this film 18 times if I didn't buy this DVD. Should I indulge myself or be a rational actor? And why am I doing this in the first place?

Final Thoughts: The Irrational High of Collecting

The other week, I found a Blu-Ray of Inception for $2.99 at a record store. "What a steal!" I thought. After completing my purchase, I nearly ran out of the shop, fearing the cashier would realize some sort of pricing error.

Standing outside the record store, holding my prize, I couldn't help but rejoice. "What idiots would price this so low," I snickered to myself. I was smitten. And then, standing there, holding a relic of a dying technology, I realized that it was I who may have been the idiot. $2.99 was a fair price for something most people consider junk. It was at this point that I got a bit sad.

But then I took the movie home, and I watched it. There was something inexplicably wonderful about watching a film that I owned. I love knowing that the movie is physically inside my apartment, and I enjoy looking at my DVD collection—marveling at the cases for prolonged periods of time (like Gollum from Lord of The Rings).

That said, I am deeply conflicted about this newfound hobby. I write articles where I rigorously quantify things, and this collector’s pursuit is quantifiably foolish.

I do not believe:

That my favorite movies will disappear from streaming services.

That I am single-handedly preserving film history, as Guillermo Del Toro has suggested.

That DVDs offer better video or audio quality, and if they did, I'm not sure I'd care that much.

That streaming is terrible and will eventually fade away.

That other people should do this.

I have one reason for collecting physical media:

Movies have been a big part of my life, and I want to own the things I love in material form.

At times, I feel as though I'm an eight-year-old collecting Pokémon cards, questing for a holographic Charizard. Forming an emotional attachment to a piece of cardboard or DVD case is a bizarre thing, but is it wrong? I don't think so. Perhaps it's best to suspend my cynicism, to stop quantifying everything ad nauseam, and simply enjoy the thrill of caring about something.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Besides the psychological pleasures of ownership I think there are some films worth buying for practical reasons...they may be retroactively edited by new corporate owners to align with modern shibboleths, or they may disappear and be hard to find later, or only be available with ads on janky streaming services. I buy Peter Greenaway films for that reason. Always interesting to me too that the director’s commentary, always touted as a benefit of DVDs, died quietly in the age of streaming. Seems not too many folk want those extra features.

I'm right there with you. It feels great. I've been buying used CDs and Blu-rays of music and movies I love so I can OWN them again. Nostalgic. Both Blu-rays and CDs also provide really great quality. And some movies and music ARE disappearing from streaming services. It feels great to own the physical items. It's fun to look at the cases.