Which Songs Are Frequently Featured in Film and Television? A Statistical Analysis

Which songs have become staples of film and television?

This analysis was conducted using data from Chartmetric, a platform that aggregates music data from streaming services and analytics providers. I highly recommend their blog, How Music Charts, which offers a variety of insightful data-centric music analyses.

Intro: "The Song Played During Hollywood Sex Scenes"

The first time I heard Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On" was in a TV show. The second time I heard "Let's Get It On" was also in a TV show, and the third time I heard this track was, once again, during a TV show. For the first 13 years of my life, I knew Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On"—which Rolling Stone ranks as the 168th greatest song of all time—as "the music they play during Hollywood sex scenes." The song's on-screen appearance typically followed a well-worn formula: two characters share a first kiss while "Let's Get It On" gently fades in, thus setting the mood for a tastefully restrained sex scene.

It wasn't until I became an active music consumer that I finally listened to "Let's Get It On" in earnest. As silly as it sounds, I had never envisioned this tune running longer than 30 seconds. Nor had I imagined that shows were leveraging the song's preexisting association with sex (independent of its use in popular media) as cinematic shorthand.

When a song becomes a staple of film and television—like "Let's Get It On"—it often takes on new life as an audio meme, repeatedly used by filmmakers to heighten a scene's emotional impact or highlight pivotal story developments. Consider the following assortment of tracks commonly featured in popular entertainment and the story beats that accompany their deployment:

"This Is How We Do It" often plays in the background of scenes depicting debauchery or partygoing.

"Tubthumping" accompanies sequences where characters smash things or fight—or both.

"Fix You" was essentially hand-crafted for the end of every Grey's Anatomy episode and shows doing their best Grey's Anatomy impersonation.

This repetitive usage fosters a well-worn repertoire of audio tropes, drawing on an audience's familiarity with every other time that track has been used in popular entertainment.

So today, we'll explore the songs frequently featured in film and television and how their usage fosters cultural discovery for younger listeners.

Which Songs Are Frequently Featured in Film and Television?

"At Last" was originally composed for the 1941 movie musical Sun Valley Serenade. Despite reaching number two on the Pop Billboard charts, the 1942 re-recording of this song and the movie Sun Valley Serenade have faded from collective memory.

In 1960, Etta James recorded a now-iconic version of "At Last," distinguished by ethereal orchestration and soulful vocals. Few songs capture the heady magic of falling in love as vividly as "At Last," making it a beloved choice for first dances and a recurring staple of film and television.

The Etta James cover of "At Last" has been invoked in so many films that it practically forms its own cinematic language:

Our main character sees someone attractive; it's love at first sight.

The scene uses slow motion, close-ups, and overhead lighting to make this newfound love appear angelic.

Then the main character snaps out of their trance, often in dramatic fashion, and the object of their desire walks away, completely unaware of our protagonist's existence.

End scene.

James' cover belongs to a select canon of songs repeatedly referenced in Hollywood productions.

To see how often "At Last" and other iconic songs appear in popular entertainment, we'll examine media citation data from Chartmetric and Tunefinder. Chartmetric aggregates music data from various streaming platforms and analytics providers, and they've generously contributed the Tunefinder data used in this analysis.

According to our Chartmetric data, Etta James' "At Last" has appeared in ~49 movies and TV shows since 1970—that's a lot of slow motion.

Much like "At Last," the rest of these tunes have longstanding associations with common storytelling tropes:

Hedonism, Partying, and Dancing: "This is How We Do It," "Push It," and "September."

Falling in Love, Dating, and Sex: "At Last," "Fade Into You," "Let's Get it On," and "Escape (Piña Colada Song)."

Getting Knocked Down and Getting Back Up Again: "Tubthumping."

Ham-fisted Emotional Manipulation: "Fix You."

If all this reads as reductive, well, that's the point.

There is often a gap between a filmmaker's intention and the audience's perception. Quality storytelling ensures viewers grasp narrative developments and remain attuned to the story's intended emotional valence. Using a widely known tune is an effective (perhaps lazy) shortcut to bridge this gap, bolstering comprehension through sonic familiarity. If a filmmaker plays "Fix You," then melodrama will ensue for the next four minutes and fifty-five seconds.

An excessive reliance on popular music as storytelling shorthand can inspire cynicism (especially when Coldplay is involved). After 40 TV show needle drops, a beloved tune begins to play like a photocopy of a photocopy.

But there is also an upside to this referential usage, as popular entertainment is one of the most effective modes for song discovery. Each "At Last" slow-motion sequence introduces Etta James to a new crop of listeners, keeping her music relevant across generations.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

How Movies and TV Facilitate Song Discovery

Discovering music is hard—and only gets harder with age. A once-effortless phenomenon becomes a labor of love, as music is no longer found through sheer osmosis. For those eager to spark the discovery process, one ever-present question persists: where will you find the next great song?

In a 2021 YouGov poll, 33% of respondents cited "Movies & TV Shows" as a consistent medium for song discovery.

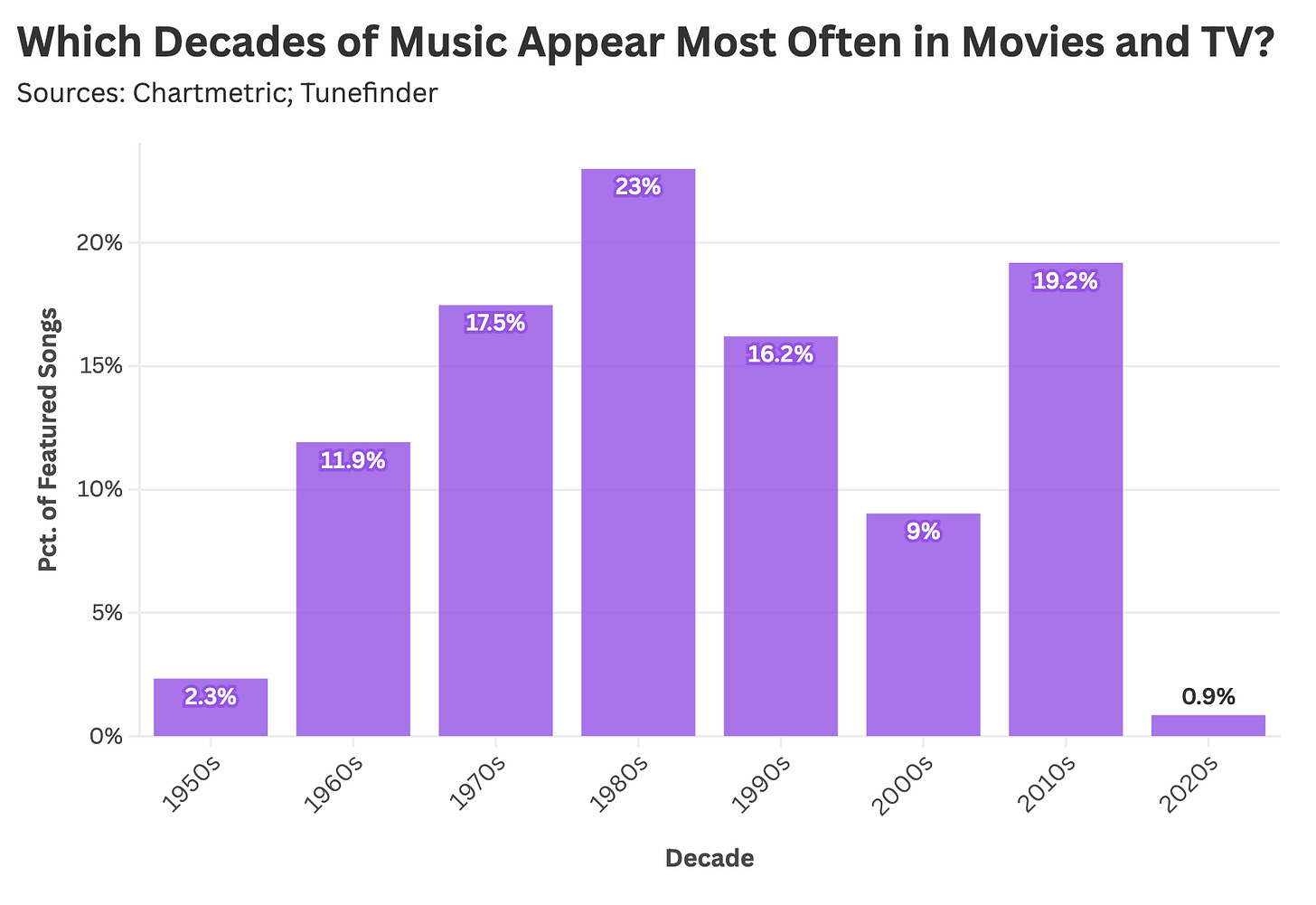

And what type of music is this audience being served? Mostly pop and rock classics. According to Chartmetric data, popular media most commonly features tracks from the 1970s, 1980s, and 2010s.

I don't know why content creators neglect the 2000s, though it's tempting to generalize about an entire decade's worth of music (maybe the 2000s stink?!).

An intriguing dimension of these audio tropes concerns the fluidity of cultural touchpoints. Are directors leveraging the music of their youth, meaning we'll always be listening to songs that came out 30 years ago, or will this canon of audio memes revolve around a fixed set of standards? My best guess—quite uncontroversially—is that it's probably a bit of both.

No matter how these songs are chosen, the outcome remains the same: many listeners would never discover these works if not for their inclusion in popular entertainment.

Consider the use of Kate Bush's "Running Up That Hill" in Stranger Things season four. Two things are notable about the mass rediscovery of this song:

Kate Bush saw an immediate spike in listenership following her appearance in Stranger Things: this is old news and was covered ad nauseam in 2022.

Kate Bush listenership remained elevated following this initial uptick: nearly three years later, streaming activity for Kate Bush remains well above its pre-2022 baseline. A new generation of listeners discovered Kate Bush, and many continued consuming her music years after Stranger Things season four.

We see similar streaming patterns surrounding Nirvana's "Something in the Way," which was prominently featured in 2021's The Batman. Mass exposure produced a sizable streaming spike, followed by elevated activity after the initial shock had subsided.

These songs went viral without social media and found enduring fandom in the process.

Final Thoughts: Context is Key

According to spreading activation theory, humans organize and interpret knowledge through interconnected semantic networks, which means a single stimulus—like a musical cue or familiar chorus—can spark a rich web of related thoughts and emotions. Every listen evokes memories of all the times we've heard that song before (or at least the most memorable occasions).

For example, whenever I hear James Blunt's "You're Beautiful," I become overwhelmed with anxiety. Why, you ask?

Well, I grew up in a community with a sizeable Jewish population, so my 13th year of life was spent frequenting Bar Mitzvahs. During this particular period of Bar Mitzvah parties, "You're Beautiful" was every DJ's go-to slow dance song. Weekend after weekend, I was left scrambling for slow dance partners—soundtracked to this song.

This godforsaken tune features a 30-second instrumental intro before James Blunt starts singing—thus igniting a frantic game of musical chairs to secure a dance partner. If unsuccessful, you would be relegated to the sidelines, watching your friends slow dance without you. For most, this tune is about someone being beautiful, but to me, it's about the humiliations of puberty.

The context surrounding our consumption of a song can shape our perception of that tune—even if this interpretation contradicts the song's intention. Recently, I listened to the "Piña Colada Song" in its entirety for the first time—a song that made our list of frequently featured tracks. This tune is a fixture of film and television, though I knew little beyond its Piña Colada-centric chorus. It's just a simple song about falling in love while drinking Piña Coladas—or so I thought (based on Hollywood tropes).

Well, it turns out this song tells a perplexing story about a failing marriage:

A man disillusioned with his relationship decides to engage in some light adultery.

He responds to a newspaper ad from someone seeking a romantic partner who likes Piña Coladas.

Turns out the narrator's wife wrote this ad because she is both frustrated with their marriage AND likes Piña Coladas.

They sort of "yada yada" the story's ending, but apparently, everything turns out fine.

Never in a million years would I have guessed that a song I first heard in Shrek was about a couple whose relationship is saved by their desire to cheat on one another and their failure to do so properly.

There are almost two entirely different Piña Colada songs:

The Piña Colada song meme: This 20-second hook is about finding a soulmate whose individuality is defined by their predilection for Piña Coladas (and getting caught in the rain).

The full Piña Colada song: A bizarro love tune about an idiot who is a lousy husband and failed adulterer (as is his wife).

Even more surprising is how the meme has kept its source material relevant despite their contradictory interpretations.

Sometimes, it only takes twenty seconds of musical magic to render a song perpetually relevant—even when listeners overlook a tune's artistic depth and reduce these works to "the sex scene song," "the Piña Colada love song," or "that Bar Mitzvah staple that ruined my 13th year of life."

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

I loved reading this post--just like your other ones!

What about short excerpts of classical music pieces? I think I've heard bits of Vivaldi's Four Seasons, Beethoven's 5th and 9th symphonies, Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture and his Swan Lake, Pachelbel's Canon, Schubert's Ava Maria, Puccini's Nessun Dorma, and so on a zillion times in movies, TV shows, and commercials. Is it just my imagination?

The Baba O'Riley erasure in this post is deafening.