What's the True Cost of NFL Injuries? A Statistical Analysis.

Do injuries dictate NFL season outcomes?

Intro: The American President and The Death Harvest of 1905.

The 1905 season was almost football's last. The Chicago Tribune referred to this particular year as "a death harvest," with collegiate and professional games resulting in 19 player deaths and 137 serious injuries.

Following the carnage of 1905, Stanford, Columbia, Northwestern, and Duke dropped football from their athletic programs, and protests mobilized in pursuit of a nationwide ban. Then the American President got involved.

Harvard threatened to drop football from its sports program, prompting Theodore Roosevelt, then President of the United States and a high-profile Harvard alum, to take great interest in the fledgling sport. Roosevelt accused Harvard of “[emasculating] football" and lobbied for rule changes to "minimize the danger" without reducing football to be "ladylike." He invited a handful of university leaders to the White House, where the body instituted a series of radical rule changes for the 1906 season.

The new regulations led to a downturn in injuries, thus salvaging the sport and its players. Teddy Roosevelt had saved football — likely at the expense of other national priorities (could you imagine if Joe Biden dropped everything he was doing to rescue Pickleball or Lacrosse?).

And while football safety has improved over time (the NFL has never been called a "death harvest"), rugged physicality continues to dominate the sport, with unpredictable absences shifting the league's competitive balance weekly. Moreover, the disorder posed by injuries is integral to some of football's greatest dramas:

Tom Brady: In 2001, quarterback Tom Brady replaced an injured Drew Bledsoe following a massive hit that left Bledsoe with a concussion, a collapsed lung, and internal bleeding. Brady excelled in the starting role and led the New England Patriots to an 11-3 record and an improbable Super Bowl victory. Brady would go on to a singular NFL career and is widely considered the greatest football player of all time.

Nick Foles: In 2018, quarterback Nick Foles took over for an injured Caron Wentz, and, similar to Brady, led the Philadelphia Eagles to an unimaginable Super Bowl championship.

These stories are intoxicating — so much so that we forget someone was hurt in the first place. We also forget that high-flying tales of underdog-replacement-turned-superstar are the exception, not the rule. For every Tom Brady, there are one hundred Not Tom Bradys:

Nathan Peterman: Nathan Peterman took over the Buffalo Bills starting quarterback position following injuries and subpar play. He threw five interceptions in the first half, tying an NFL record, and was subsequently benched.

Dan Orlovsky: Detroit Lions quarterback Dan Orlovsky assumed the starting role following a series of injuries and infamously ran out of the back of his own end zone (which is the opposite of what you want to do).

Injuries function as football’s chaos monkey — in a split second, one brutal collision can cause a player to lose their career or a team to lose its championship aspirations. So what are the quantifiable impacts of football injuries? How often do they occur, how do they shape the sport's economics, and how do they change team outcomes?

Methodology: How Do Injuries Impact the NFL?

Our goal is to examine the impact of injuries on various aspects of professional football.

Dataset:

We'll be using several datasets to craft a holistic picture of injury trends and their resulting consequences:

Analysis Questions:

What is the NFL injury rate relative to other sports? And how often are players hurt?

How much salary is paid to players absent with injury? And which type of injury (ACL, concussion, etc.) causes the most significant losses?

How do injuries impact season outcomes? And how do results vary due to the magnitude of loss (number of players, position, total salary, etc.)?

How do injuries alter the NFL's competitive landscape? And which team has been least lucky over the past eight seasons?

1. Which Sport Hurts Most?

Upon graduating college, Oklahoma's Kyler Murray was a highly-touted baseball and football prospect, earning first-round selections in both drafts. In 2022, Murray signed a five-year, $230.5 million contract extension to play football for the Arizona Cardinals, securing his future in the NFL. Murray's $46.1 million annual salary nearly surpassed the entire 2022 payroll of the Oakland Athletics — the baseball team that drafted him in 2018.

It sounds like Kyler Murray got the better deal — though it depends on how you define better. Murray suffered a torn ACL this past season, an injury that mandates major surgery and a substantial rehabilitation process. So Kyler got paid more than an entire baseball team, but he sustained a debilitating injury (one rare to baseball and common in football) with long-lasting repercussions. Much like life, picking a sport is but a series of trade-offs.

An athlete's chosen game dictates earning potential, the probability of making the pros, career longevity, and the likelihood of injury. When we look at the incidences of injury across professional sports, we find football to be the clear leader:

Football players are ~8x more likely to get injured than baseball players and ~2x more likely than hockey and basketball players. Is this surprising? Not really.

The average NFL playing career lasts 3.5 years, during which time players will likely miss 1.25 games per season due to injury and six total games throughout the course of their career:

33% of players will avoid injury their entire career, but this lucky cohort mostly consists of specialists (kickers, punters, and long snappers) and back-ups (mainly quarterbacks). Coincidentally, these positions are often mocked for their perceived frailty (it's a no-win situation). So, odds are you will get hurt if your role entails hitting or getting hit.

And when that fateful injury arrives, what will that ailment be?

Knee injuries dominate nearly 30% of all player absences, followed by a long tail of other maladies. Moreover, the long tail of injuries is spread across numerous body parts (almost every human appendage), underscoring the full-bodied sacrifice required by the sport.

So did Kyler Murray choose right? Who knows. He should, however, have enough money to buy a Stair Assist to aid with any mobility issues developed in old age.

2. The Economic Cost of NFL Injuries

Football began as an amateur sport, a proving ground for men to test their faculties and cultivate discipline. High-profile games were played amongst collegiate programs, athletic clubs, or company teams — all for free. And then Pudge Heffelfinger came along.

William "Pudge" Heffelfinger (a man with a genuinely awe-inspiring nickname) was the first athlete to play American football professionally, having been paid to play in 1892.

Heffelfinger was widely considered the best player of his day. In the late 1800s, two Pittsburgh teams enjoyed a heated rivalry, often scheming for a competitive advantage in their frenzied matches. Hilariously enough, both teams approached Pudge to participate, with the first team offering a payout of $250 (equivalent to $8,153 today) and the second team doubling that amount to $500 (equal to $16,307 today). Pudge accepted the second offer, thus completing the first known free-agent transaction in football history.

Since that time, football has grown into an economic juggernaut. The Super Bowl alone commands a $5.6M price tag per commercial for a rate of $187k per second of air time. And yet there is a cold reality to the business of football, as players incur significant damages in service of the game. As such, one has to wonder how bodily sacrifice affects the NFL's distribution of earnings.

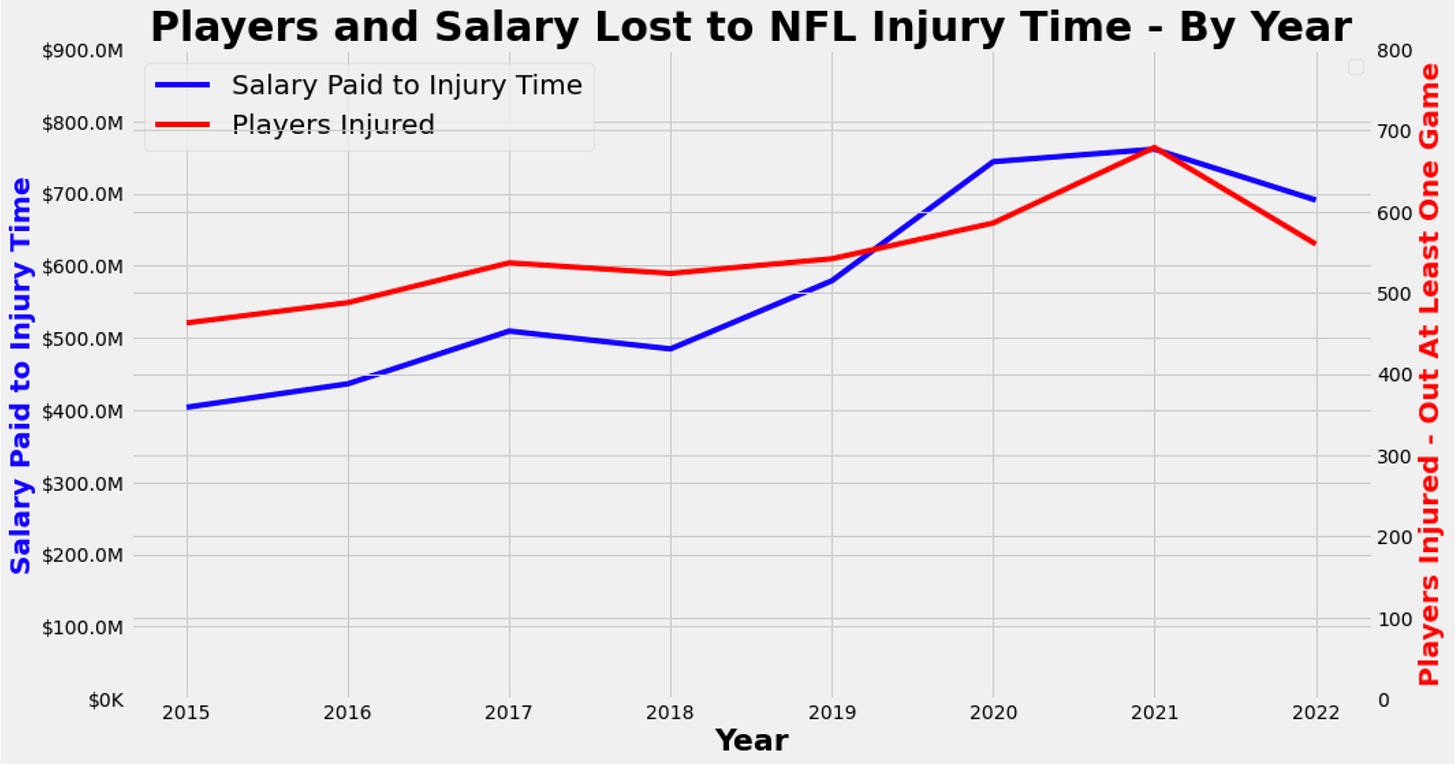

For starters, the rate of injuries and the salary paid out to players missing games has steadily increased over the last few years:

The 2022 regular season saw nearly $800M in salary paid to injured players, with over $130M lost to knee injuries alone:

Between 8% and 12% of total compensation is distributed to players missing games. Cash paid to injured players prompts a complicated debate over the economic value of these payments, as teams and players confront misaligned incentive structures.

Does the prospect of injury increase salaries, especially those of star players, or drive down pay, given the need to field a team of greater depth? And how should players be compensated when their bodies pay such a steep price?

The National Football League Players Association (NFLPA), a labor coalition representing the players, is arguably the world's most powerful union and focuses on negotiating the terms of the league's collective bargaining agreement (a profit-sharing arrangement between owners and players).

In 2021, the collective bargaining agreement allocated 48% of the league's $17.19B revenues to player compensation, a mind-boggling departure from the days of amateurism and the handshake agreement forged by Pudge Heffelfinger and the Allegheny Athletic Association.

3. Do Injuries Lead to Lost Games?

If you've ever watched a post-game interview with an NFL head coach, you'll notice the near-ubiquity with which they cite injuries as a significant factor in team performance. And they're not wrong, but every team is dealing with injuries. So are the coaches correct, or are they simply making excuses? How much do injuries impact a team's win total?

To better understand the relationship between player losses and team outcomes, I utilized our injury dataset to train a series of one-variable models to predict season win totals. In addition to forecasting, our models express the quantitative relationship between our selected variable (the magnitude of losses) and a team's resulting win differential:

As you can see, the caliber of players lost (as determined by salary) matters. Furthermore, losses compound, especially when high-salaried players miss time together.

Next, I trained a model to forecast win totals as a function of position loss (quarterback, running back, etc.). Our training data centers on players of above-median salary who missed five games or more. We can then graph variables the model deems as significant:

Some positions are more replaceable than others. Losing a quarterback serves as a dementor's kiss for a team's title hopes, as only four backup quarterbacks have ever won a Super Bowl.

On the other hand, running backs are easier to replace. Bill Belichick, the ruthlessly efficient and somewhat grouchy head coach of the New England Patriots, places minimal importance on any single running back. Instead, Bellicheck appears content moneyball-ing his way to victory, employing a stable of players to address the needs of the position collectively.

So are coaches right to complain? Yes, conditional upon the magnitude and area of loss. If they lose their quarterback and/or +$30M of payroll to injury, then statistically speaking, the coach can claim bad luck (and we can give them a participation trophy or something).

4. How Much Do Injuries Impact An NFL Season?

So we've established that players get hurt a lot, that it's terrible to lose your best players, and that running backs aren't that important (especially if you're Bill Bellicheck). But how does this manifest in a team's final record, especially when all teams incur varying degrees of injury throughout the season?

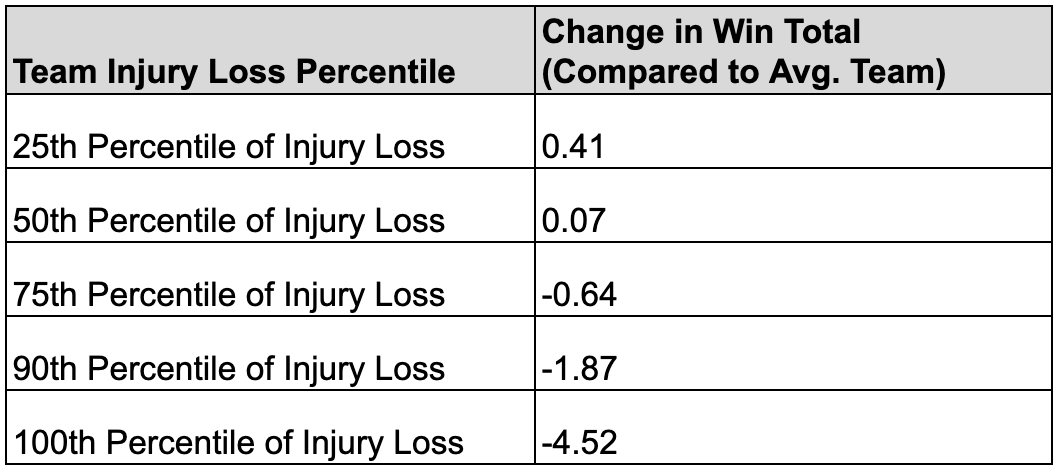

I used our full roster of variables in training a model to predict win totals for every team over the previous eight seasons. These projections produce a distribution of outcomes regarding injury impact, with results ranging from non-significant to full-on trainwreck:

Our spectrum of win total predictions is a tale of two season archetypes: 1) a majority of teams within a standard range of injuries and 2) a handful of teams with terrible luck:

For those within a standard range of injury losses (around 90% of teams): this cohort includes both high and low-quality teams, but only a tiny fraction of incremental wins/losses can be attributed to roster issues — somewhere in the range of plus-or-minus 0.5 wins.

For those with terrible luck (around 10% of teams): these franchises experienced roster turnover well outside the standard range, losing a quarterback and/or several star players, and thus experienced a significant decline in season win totals — somewhere between 2 to 4.5 incremental losses relative to the average team.

And which teams and seasons qualify as overwhelmingly unlucky? The following chart will mean little to those who do not follow the sport. Apologies. For diehard NFL fans, let this list serve as a reprieve for a tortured season you'd like to forget. It wasn't your team's fault! It was just injuries!

All our hapless NFL seasons include a significant quarterback injury, over $30M salary paid to players missing time, and ~15 to ~20 players missing five games or more. That's a lot of pain — for players and fans alike.

Final Thoughts: Are Injuries Quintessential?

In January 2023, Buffalo Bills player Damar Hamlin collapsed during a routine football play. Hamlin's heart stopped beating upon crumbling to the turf, and he was subsequently revived twice, once on the field and once on his way to the hospital. Hamlin survived and will go on to live a normal life, but the incident shook many football devotees.

NFL fans are accustomed to brutality. We've seen broken bones, torn ACLs, savage collisions, and so much more — with each injury replayed in slow motion for our viewing pleasure. And yet the Damar Hamlin incident was something different, something new. This injury was not some future clip in a youtube compilation of ferocious hits; this injury was a collective trauma for the NFL and its fanbase. Sure, it may sound dramatic, but nobody wants to watch another human being die.

And yet Hamlin's injury provokes questions regarding fan tolerance for brutality. Are we too desensitized to football's gladiator violence? Are fatalities the only unacceptable form of harm? Personally, I can't remember the last time I was shocked by a high-profile injury.

To be clear, this is not some plea to end football. I accept football will continue as a physically taxing sport. But sometimes I wonder why I like football in the first place. Why do we enjoy such a grueling sport? What makes football infinitely watchable?

Well, for one thing, it's wildly unpredictable and, therefore, wildly entertaining. Every game and every season are defined by chaotic randomness, as a single play can have significant ripple effects across the league. And what is a massive contributor to this ever-fluctuating chaos? Injuries.

Football’s awe-inspiring brutality, and the myriad injuries it spawns, are central to the game’s DNA — it's what Teddy Roosevelt sought to diminish and preserve, and somehow he managed both simultaneously. Injuries gave us Tom Brady. Injuries gave us Nathan Peterman. Injuries single-handedly wrecked the Tennessee Titans' 2022 season. And injuries will continue to make every NFL Sunday a bit more unpredictable, though it all comes at a cost.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

What period is your data from? The chart of injured teams at the end only lists teams since 2018.

Correction: Nick Foles replaced Carson Wentz