The Rise and Fall of Movie Musicals. A Statistical Analysis

What happened to movie musicals?

Intro: What Happened to Movie Musical Trailers?

In July of last year, Warner Brothers dropped the first trailer for its long-awaited Wonka musical, a dazzling two minutes of razzmatazz, ornate sets, choreographed dance, but no apparent singing. The omission of Wonka's musicality showcased an emerging trend in movie musical marketing—a sparkly advertisement sans the "musical" part. Weeks earlier, a trailer for an adaptation of Broadway's The Color Purple significantly downplayed the film's singing, flashing shots of potential song and dance numbers without a sustained depiction of theatrics. Maybe a diehard theatre-lover comprehended that Wonka and The Color Purple were musicals, but would the average moviegoer catch on?

Things got even weirder in November of this past year when a trailer for a Mean Girls musical was soundtracked by an Olivia Rodrigo tune rather than utilizing music from the movie itself. The internet erupted with confusion, with NBC News noting, "Mean Girls movie musical trailer met with confusion over lack of music," and HuffPost quipping, "Mean Girls Movie Musical Trailer Has Everything But The Music." Clearly, the makers of this trailer wanted audiences to believe that this was a Mean Girls remake—only to be surprised when Regina George broke out in song.

Is it better to trick audiences, frustrating deceived moviegoers, than accurately depict a forthcoming musical? Is this format so polarizing that it's better to lie?

Musicals used to be among Hollywood's go-to genres, as blockbuster hits like The Wizard of Oz, The Sound of Music, and Mary Poppins captivated audiences. But in recent years, the film industry has largely moved away from musicals, releasing fewer productions and obscuring the content of these projects when marketed. So today, aided by David Benkofwriter of The Broadway Maven (who provided helpful trivia for this piece), we'll explore the rise and fall of movie musicals.

The Rise of Movie Musicals

The first words ever spoken on screen were in a musical. In 1927, Warner Brothers released The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue and music, revolutionizing the movie industry and marking a shift from silent films to "talkies." The movie features entertainer Al Jolson shouting the immortal line, "You ain't heard nothing yet," before breaking into song and dance, a feat that mesmerized audiences.

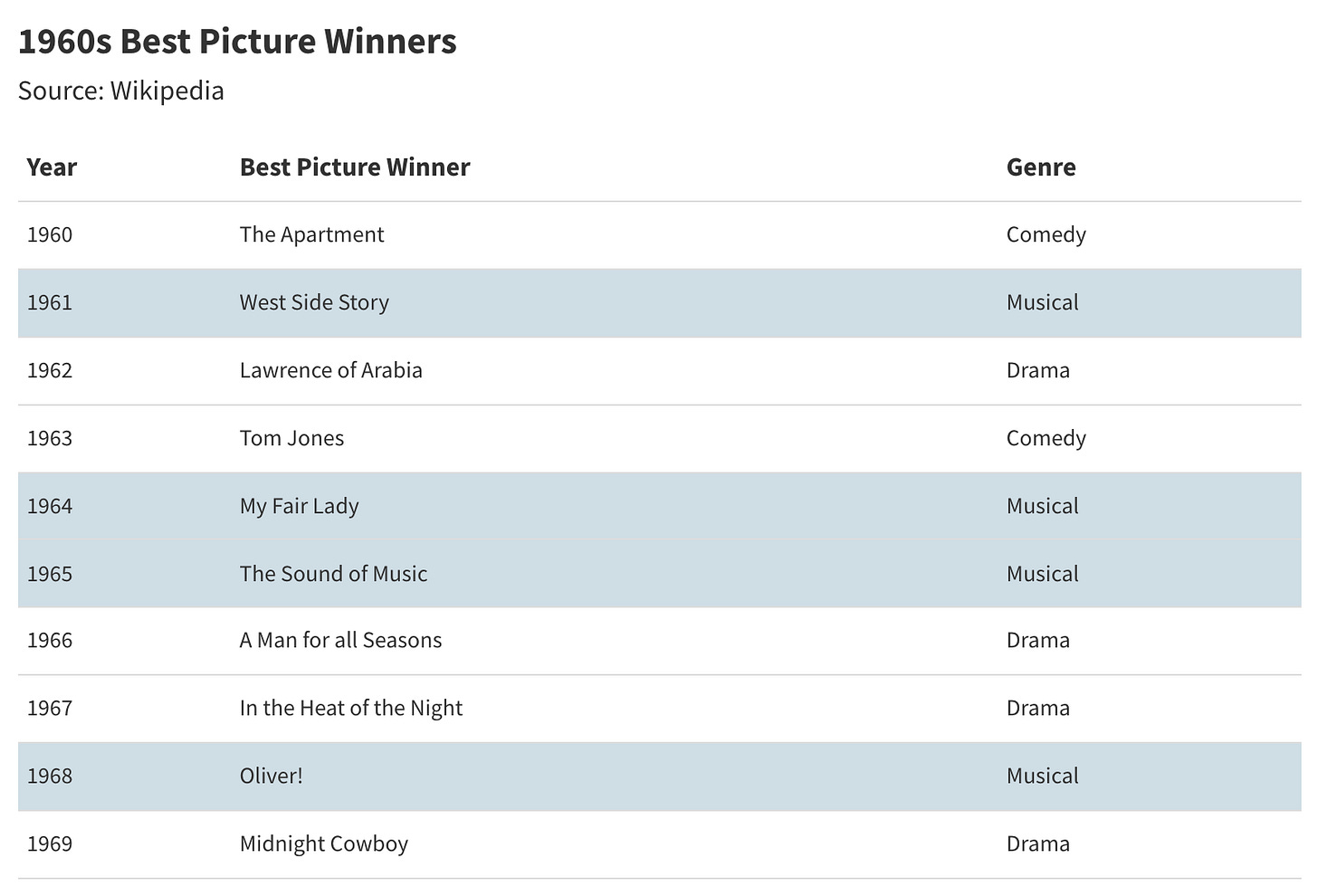

The advent of sound (and later color) made musicals a staple of early 20th-century cinema, as the genre became a prime vehicle for showcasing cutting-edge filmmaking techniques through original scores, grand sets, colorful costumes, and extravagant dance numbers. Over the next few decades, The Wizard of Oz, An American in Paris, Singin' in the Rain, and Meet Me in St. Louis would achieve massive mainstream success, elevating the commercial relevance of the genre. The format arguably peaked in the 1960s as four of the decade's Best Picture winners went to big-budget musicals.

But the success of live-action movie musicals is only half the story. In 1937, Disney, who had just shifted from animated shorts to feature-length films, incorporated original songs into its premiere picture, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The astounding success of Snow White and the popularity of its musical numbers set a precedent for Disney, as the studio continued to integrate music into its movies as a signature storytelling element.

Disney made original songs a staple of their productions, guaranteeing the genre perpetual mainstream relevance, at least in animated form. Of the top 50 grossing films of all time, 11 are movie musicals, 10 of which are Disney productions.

When we look at the most successful movie musicals of all time (live-action and animated), as measured by adjusted box office, we see periods of Disney dominance intermixed with eras marked by successful Broadway adaptations.

The 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s brought a string of megapopular animated musicals like Snow White, Cinderella, Pinocchio, and Peter Pan.

The 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s were down years for Disney, and during this time, a series of blockbuster Broadway adaptations of My Fair Lady, Grease, and The Sound of Music achieved tremendous mainstream success.

The 1990s and 2000s saw a return to form for Disney and the rise of Abba's Mamma Mia juggernaut. Over the next three decades, Disney would bring us The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin in live-action and animated formats, while Abba would bring us Mamma Mia! and Mamma Mia: Here We Go Again!

Since the 1970s, a handful of non-Disney musicals have achieved commercial and critical success. Chicago won Best Picture in 2002, La La Land won Best Picture for five awkward minutes in 2016, and Les Misérables made a lot of money despite Russell Crowe's terrible singing.

And while musicals are far from extinct, their status as a box office draw has slowly faded. Live-action works, in particular, have struggled to find their footing in a film landscape dominated by superhero fare, prestige dramas, and low-budget horror films—a far cry from the genre’s cultural preeminence in the 1950s and 1960s. Once a movie theater mainstay, the format has fallen on hard times, with few adaptations escaping Hollywood's hellish development process to reach the big screen.

Need Help with a Data Project?

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data science and data journalism consulting services. Reach out if you’d like to learn more.

Email daniel@statsignificant.com

The Decline of Movie Musicals

The latter half of the twentieth century saw a steep decline in movie musical production. Disney has maintained its yearly release of one to two animated musicals (and probably will until the end of time), while the number of live-action projects has notably declined. In the 1930s, around 10% of all films were musicals. Today, that number sits below 1%.

Musicals fell out of fashion in the 1970s and 1980s as several high-profile box office failures made studios wary of investing in the genre. The enormous success of 1965's The Sound of Music spawned a string of big-budget, lower-quality projects like Hello Dolly, Doctor Doolittle, Camelot, Xanadu, and Lost Horizon, marking the end of the format's dependability. At the same time, television offered an alternative form of musical entertainment, reducing the novelty of song and dance performances on the big screen, while American film culture shifted toward "serious" and "relevant" movies (The Deer Hunter, Taxi Driver, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, etc.), rendering musicals out of touch and old-fashioned.

Examining online ratings for movie musicals, we see a sustained drop in acclaim for films released following the 1970s.

Sure, these online reviews are being logged in the 21st century, far removed from the days of Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, and Fred Astaire. Still, this retrospective appraisal may speak to the format's ideal presentation (what people expect from the genre). When I think of live-action movie musicals, I envision The Wizard of Oz, West Side Story, and Singin' in the Rain, big-budget spectacles from Hollywood's golden age—a canon of films released between 1930 and 1970. The format, which thrived in the theatrical setting provided by studio sound stages, has struggled to adapt and remain relevant as filmmaking techniques evolved.

Modern movie musicals have had difficulty establishing their place in today's box office environment—though this is not unique to the format (as Rom-Coms and mid-budget movies have also petered out). There is an unfortunate economic reality to the viability of entire genres. Movie musicals saw massive returns in the 1960s, followed by a steep drop-off in gross through the end of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, action, family, and fantasy films began to dominate the box office, offering consistent profits for studios seeking highly lucrative blockbusters. In Hollywood, films are quantifiable products with distinctive economic profiles and differing levels of built-in appeal. Unfortunately, musicals are unable to produce the billion-dollar returns of action franchises, and they are not cheap enough to yield a modest profit, like that of low-budget horror films or prestige indie dramas.

As such, the live-action musical is stuck in a middle ground of sorts—popular enough to hit on occasion but not a standard project for risk-averse studios. Even worse, the polarizing reception of musicals further muddies Hollywood's affinity for the genre. Some people don't like Broadway, plain and simple, while others worship at the altar of Streisand and Idina Menzel (and if you don't understand who these people are, you're probably in the former bucket).

In a previous piece, I examined the factors associated with polarizing films using star ratings and online tags from a film community called MovieLens. The site allows users to rate movies on a scale of 1 to 5 and encourages viewers to tag films with details of story, cast, setting, and technique, such as "3D," "Africa," "Bill Murray," "violent," "whimsical," and more. When examining rating variance by user tag, "musical" was a storytelling characteristic associated with projects of heavily mixed acclaim.

Presumably, the genre's divisive appeal led recent trailers to downplay song and dance content. Theater lovers will seek out musicals, while others may need further convincing (or to be deceived, apparently). Sadly, producers will only invest in Broadway adaptations if they can guarantee broader appeal, like the cultural cache of ABBA or the celebrity of Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone.

Instead, live-action musicals have become a rarity, spawning a vicious cycle where the genre's scarcity leads to waning interest in the format. Over the last twenty years, online searches for "Movie Musicals" have significantly decreased, despite a spike in 2016 likely spurred by Hamilton and La La Land and a slight increase in 2021 driven by Steven Spielberg's West Side Story.

Audiences are receptive to the format, with searches increasing in response to a breakthrough hit. And yet, in the absence of future musicals emerging within the zeitgeist, appeal may continue to wane. What's left is a chicken-or-the-egg problem. The genre needs more mainstream entries to stoke interest amongst average moviegoers; however, few producers want to gamble on a musical without pre-existing moviegoer interest.

Final Thoughts: The Rise of Non-Musical Musicals

My sister is obsessed with all things Broadway, and I, being her little brother, was forced to watch everything she watched. As such, I have seen all iterations of Les Misérables, I have watched Rocky Horror Picture Show more than ten times (though I still haven't seen the ending), and I know the names of many Broadway divas. I am pro-Broadway and pro-movie musical.

On my first day of film school, we watched Singin' in the Rain on 35mm. I had never seen this movie on the big screen, and I was enthralled with Gene Kelly's acrobatic dancing, the colorful sets, and the memorable songs. When the picture finished and the lights came up, I turned to the person beside me and said, quite earnestly, "That was so cool."

My seatmate shook their head with disapproval and exclaimed, "That was so f-ing boring." This was a shock. I was raised in a house where Broadway was monoculture; I had never considered it niche.

A few weeks ago, my wife and I went to the movies and saw the now-infamous non-musical Mean Girls trailer. My wife, who does not like Broadway, was ecstatic at the notion of a Mean Girls remake. It was at this moment that I had the unfortunate pleasure of telling her that it was, in fact, a musical in disguise. Immediately, she was disappointed, "why would they do that?" she sighed.

But then something funny happened. A few weeks later, my wife told me she had changed her mind; she wanted to see the Mean Girls movie. Was this new form of movie musical marketing working? Had movie studios Trojan-horsed song and dance into the hearts and minds of average moviegoers? Maybe. As of this writing, Wonka and The Color Purple top the box office, two camouflaged musicals with encouraging returns, a promising (if not slightly confusing) sign for the format.

Musicals will never die; too many people love the genre for that to happen. Perhaps they will continue their trajectory as a small niche within the film industry. Or maybe these stories have broader appeal—provided moviegoers are not told of their content in advance.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Has there ever been a good movie musical that did not become a hit? Musicals are perhaps the most difficult kind of movie to make and most filmmakers can't pull them off. So, we often end up with bad movie musicals, which then cause critics to announce the death of the movie musical. Every year, of course, there are dozens of terrible action and horror films, but no one reacts to them by declaring the death of those genres.

Time for Cop Rock: The Movie.