Do Most Artists Peak With Their First Album? A Statistical Analysis

Is an artist's first album usually their best?

Intro: Hootie & the Blowfish

People have strong feelings about Hootie & the Blowfish. The group’s unusual combination of fleeting success and cultural omnipresence has made them shorthand for a one-album wonder. If you’re a diehard Hootie fan, especially the Blowfish-deep-cuts, then you’ll want to skip the next two paragraphs.

Hootie & the Blowfish’s debut album, Cracked Rear View, was a generational success, selling over 21 million copies in the U.S., spending a year on the Billboard Album Charts, and producing six Top 40 singles. Songs like “Let Her Be” and “Only Wanna Be With You” became fixtures of radio rotations—so ubiquitous that DJs joked pulling Hootie off the air or leaving them on generated the same number of listener complaints.

Hootie’s second album arrived two years later and was deemed a commercial failure relative to the band’s pedigree, selling just 20% as many copies as its predecessor. Critics derided the record as “safe,” expecting a dramatic evolution of the band’s sound. In hindsight, Hootie’s much-maligned sophomore effort exemplifies the second-album trap: a follow-up judged less on its own merits than against the impossible expectations set by a debut.

There’s a well-worn saying in the music industry that “You spend your whole life making your first album, and a year making your second.” This adage offers a tidy explanation for the second-album trap while also presuming that most premieres will outshine everything that follows. Given the ubiquity of this maxim, I wanted to test whether this wisdom is quantifiably true. Is the first album always the best?

So today, we’ll examine whether artists peak with their debut, map the prototypical trajectory of pop stardom, and explore the unforgiving nature of a career in music.

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by Shortform

Learn More, Faster with Shortform’s Book Summaries

If your days are short and your reading list is long, check out Shortform.

Shortform creates concise, high-quality guides to the best non-fiction books. Think book summaries, but done well: Shortform breaks down key concepts, with additional analysis and exercises to help the insights stick.

From self-help to statistics — Shortform makes the world’s best ideas easier to access. Unlock thousands of titles for less than the price of one book.

Save $50 off an annual plan here.

Do Most Artists Peak With Their First Album?

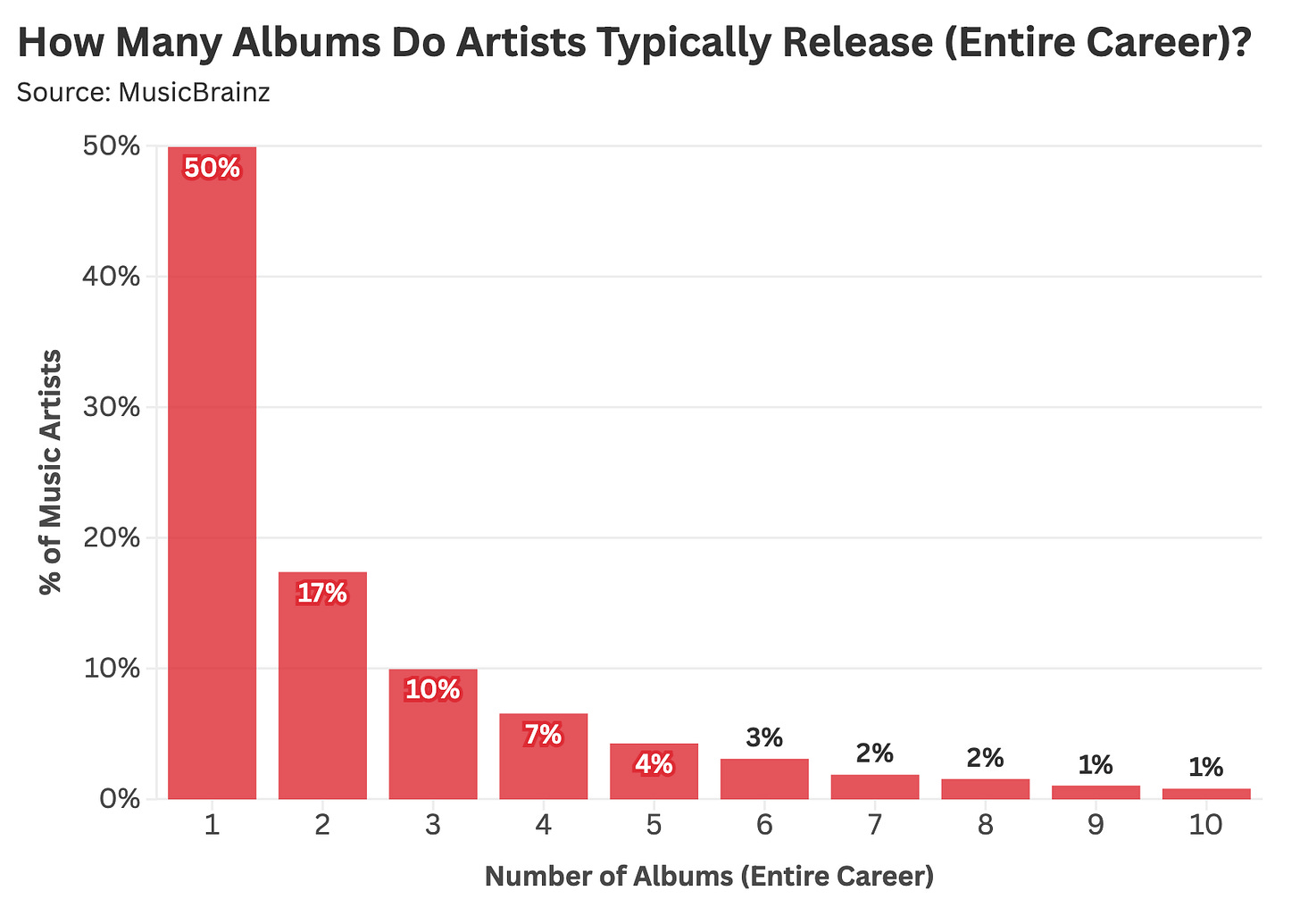

Here’s a cheeky—and decidedly annoying—answer to today’s central question: an artist’s first release is typically their best and worst album. That’s because most musicians produce one record before an early retirement.

Our dataset likely understates the prevalence of one-record careers since many debut albums lack notoriety or a durable digital footprint. As such, the question we’re answering today is slightly more nuanced: amongst artists who release multiple albums, is the first usually the best?

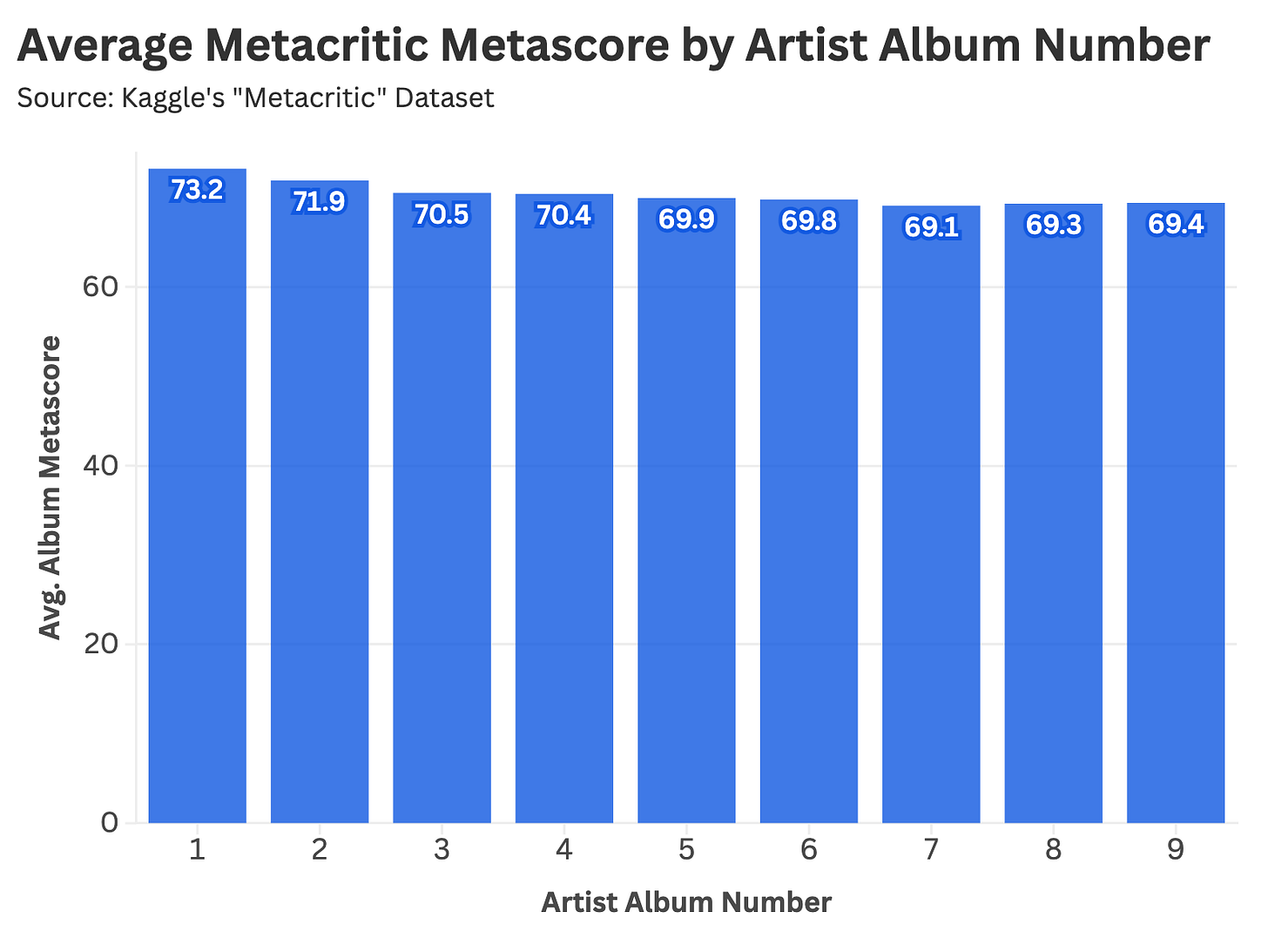

The short and simple answer to this prompt is also yes. When we look at average Metacritic Metascore by album number, we see a significant drop-off between an artist’s debut and subsequent releases.

Most music acts see declining critical acclaim with each successive record, before scores level off around their fifth album (if they make it that far).

While this answer may seem conclusive, it comes with an important caveat: artists who release more than one album are subject to survivorship bias—their debut was strong enough to justify a follow-up. Such a pattern will always inflate the value of an artist’s first release. This phenomenon led me to approach the question from a different angle altogether: how many truly great albums are debuts?

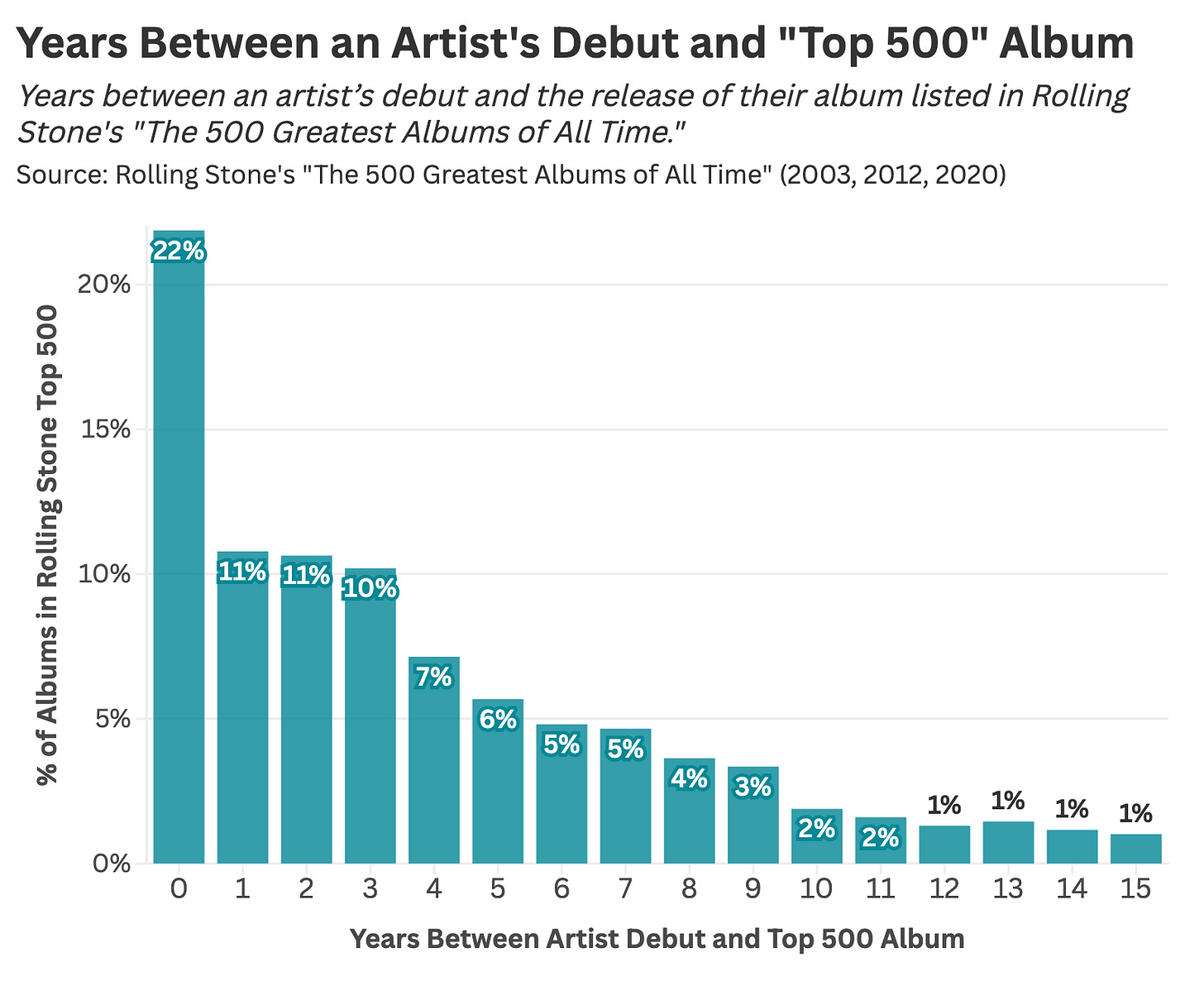

To measure the seniority of masterworks, I compiled every entry cited in Rolling Stone’s Top 500 Albums lists (spanning the 2003, 2012, and 2020 editions) and calculated the time between an artist’s debut and the release of that record.

While first albums are frequently included in Rolling Stone’s Top 500, 78% of masterpieces come after a debut.

Before we move forward, let’s recap our findings thus far:

Most artists release one album before calling it quits.

Those who earn the chance to make a follow-up often struggle to surpass their debut, precisely because their first album was good enough to justify a second—and third—record.

Artists who create generational masterpieces typically produce multiple albums before reaching their artistic peak.

Taken together, these data points raise questions about the relationship between artistic achievement and longevity. According to our Rolling Stone Top Album data, 54% of masterworks arrive within the first five years of an artist’s career, a pattern that hints at the trajectory and fragility of creative success.

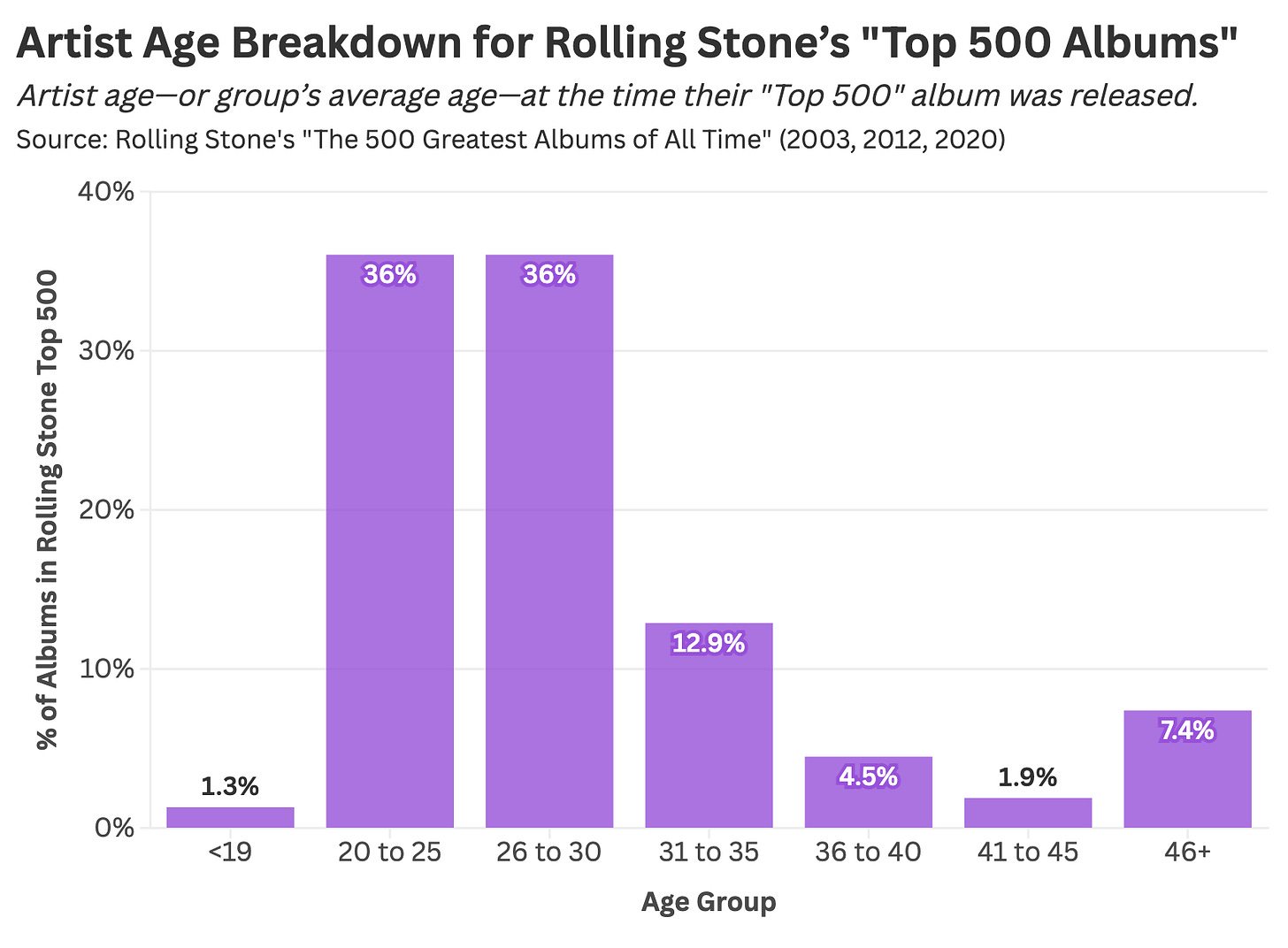

Of the combined entries on Rolling Stone’s Top 500 lists, over 70% of albums come from artists in their 20s (or groups with an average age in their 20s).

I would never seriously consider financial advice from someone in their 20s, yet when it comes to masterful music, we’re usually talking about artists in this age group.

This factoid represents a significant deviation from a career in film, where actors and directors typically “peak” in their 40s and 50s, using long-gestating career capital to produce a magnum opus.

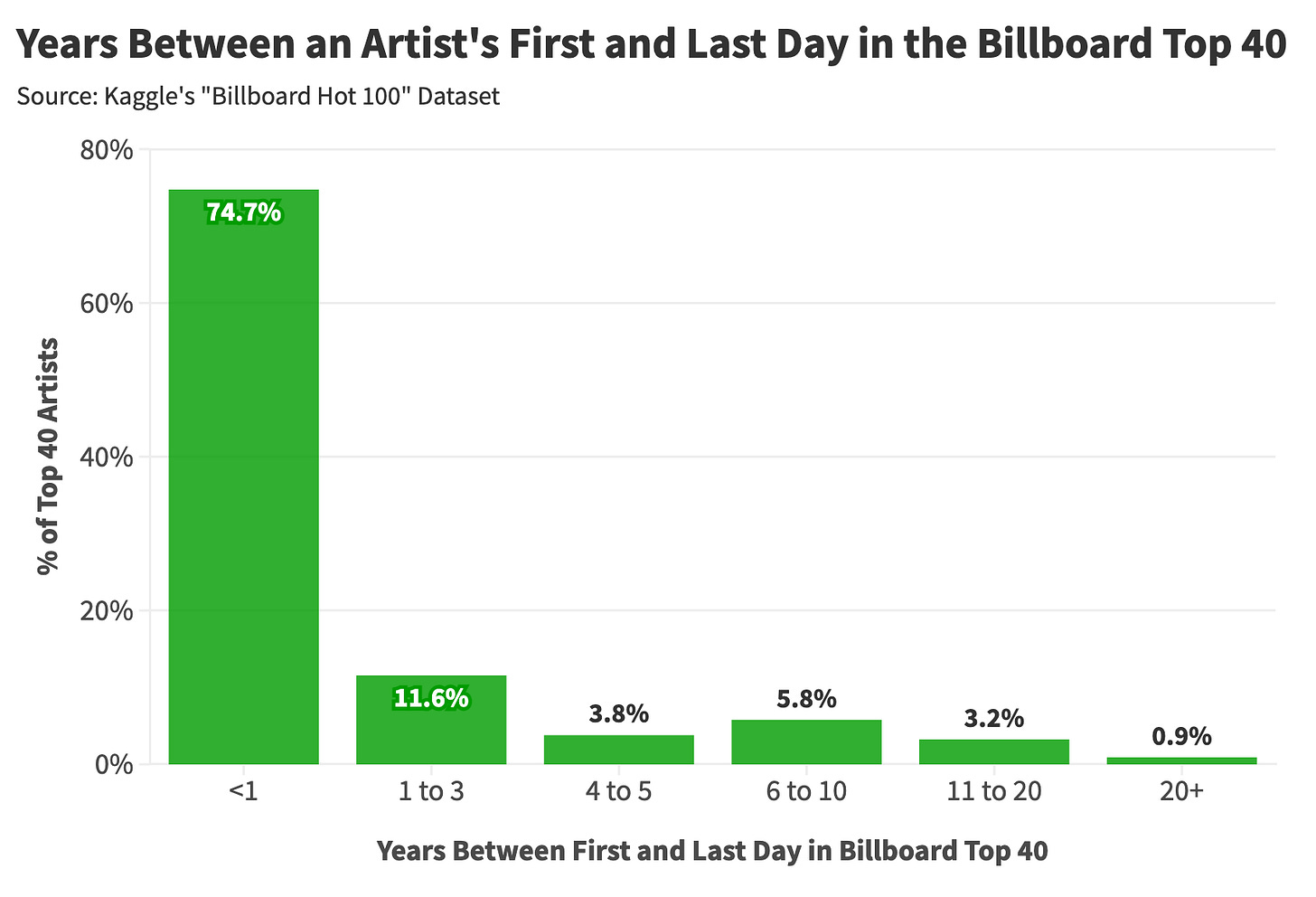

Crazier still, music acts who receive mainstream recognition usually see this acclaim dissipate just as quickly. When we examine the time between an artist’s first and last day in the Billboard Top 40, most achieve this feat for less than a year (the majority under four months).

All of these data points lead us to the same conclusion: pop music is, for the most part, a young person’s game. Whether someone is giving up after their first album, breaking into the Top 40 for the first time, or creating an all-time classic, the odds are high that they’re in their twenties—and have released only a handful of records, if any at all.

One explanation is structural: the music industry operates as a tournament-style incentive system, rewarding artists who succeed early with continued investment. But this Darwinian sorting raises a deeper question: why do artists struggle to surpass themselves as their careers progress? Is there a sociological bias against follow-up work, or is it simply difficult to produce multiple albums that resonate with rapidly changing tastes?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: What Happens When Your Favorite Band Keeps Making Music?

When I was in college, I discovered LCD Soundsystem and promptly canonized the band as my favorite artist. Approximately ten minutes after making this decision, I googled them and found out that they were retiring. After five minutes of grieving, I decided their early retirement was somewhat ideal—I could be the guy who loves a short-lived indie sweetheart. I would buy all three of their vinyls, and whenever the band came up in conversation, I’d say things like “it’s a shame, but they left us with three incredible albums.” Whoever I was talking to would nod approvingly, impressed by my mature acceptance of the band’s fleeting brilliance.

For five glorious years, I had it all figured out. Then they un-retired.

Not only did LCD Soundsystem return to touring, but the band also released a new album. And guess what? I did not like their new stuff. This left me with an extremely low-stakes existential conundrum: Can you still love a band once its legacy is no longer frozen in amber? How do you preserve the idea of an artist when they make new work that interferes with this mental model?

My oddly specific (and self-centered) relationship with LCD Soundsystem captures the opposing forces that shape an artist’s debut and the long shadow it casts over the rest of their career. When an artist emerges, we’re struck by the novelty of their sound; they stand out by offering something recognizably different. It’s at this point that a music act becomes subject to identity lock-in.

In this context, identity lock-in freezes an artist’s cultural appeal at an early, defining moment—with all future work judged against that fixed identity rather than by its own merits. With few exceptions, our relationship to a beloved music act is anchored to a narrow window in time. In my head, My Chemical Romance will always be a band of moody, goth twentysomethings, but according to an image recently displayed on Spotify, the band is subject to a linear theory of time. They are now in their forties and a little less goth.

What’s strange about this phenomenon is how tightly our expectations become bound to a name. We associate a particular sound and feeling with the words LCD Soundsystem or My Chemical Romance, and in doing so, impose those expectations on the people behind the name. Few careers illustrate this better than that of Darius Rucker. Today, Rucker is one of the best-selling country artists of the 21st century, blending traditional genre conventions with singer-songwriter sensibilities and pop polish. He was also, famously, the frontman of Hootie & the Blowfish.

By launching a solo career, Rucker escaped the gravitational pull of Hootie fandom and the expectations associated with this once-ubiquitous brand. It’s the same voice and much of the same songwriting DNA—but under a different name. Perhaps the simplest way to avoid the second-album trap is to keep making debut albums.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

I have thought about these issue for years without achieving anything like the clarity you did here. Hope you return to this topic because there are more interesting questions to ask (eg solo artists vs bands) and have a hunch the data has more secrets to reveal.

"Perhaps the simplest way to avoid the second-album trap is to keep making debut albums." Reminds me how in the comic book world, they always release a new #1 with whatever retconning reason.