Why Don't Americans Care About Formula 1? A Statistical Analysis.

How Formula 1 failed in America, and how it's turning things around.

Intro: Too Fail to Big.

The 2005 American Grand Prix was an unmitigated disaster. At the start of the race, all twenty cars lined up on the grid, but following an initial formation lap, fourteen teams pulled off the road and retired their vehicles in protest of poor track conditions, leaving six drivers to finish the contest.

Fans were livid. Boos cascaded throughout the stadium as disgruntled spectators threw beer cans on the track. By lap 10, many of the estimated 100,000 attendees left the grandstands, with thousands demanding refunds. Police were eventually called in to keep the peace.

The 2005 grand prix was another epic fail in America's fraught relationship with Formula 1. Year after year and disappointment after disappointment, one of the world's largest sports eluded traction in the US market. And then, improbably, a docuseries changed everything.

Netflix's Drive to Survive premiered in 2019 to considerable acclaim, with nearly 300,000 first-week viewers. The docudrama provides exclusive access to the emotional rollercoaster life of Formula 1 drivers and executives. Since the show's premiere, US F1 fandom has increased a remarkable 33%, with more than half of converts crediting Drive to Survive as the impetus for their newfound interest. I guess art can change the world.

But why did adoption take so long in the first place? Formula 1 is a global juggernaut, with an estimated 445 million viewers worldwide, and yet American audiences largely ignored F1 for the first seventy years of its history. What slowed Formula 1's stateside expansion?

Methodology: What Slowed American Formula 1 Adoption?

Our goal is to provide a quantitative explanation for Formula 1's sluggish growth in the US market, pre- Drive to Survive.

Analysis Questions:

We'll examine several theories surrounding F1's struggle to court American audiences, including:

A long history of American Grand Prix disasters.

Lack of long-running American F1 racing events (and tradition).

Adverse impacts of global time difference.

Oversaturation of sports content in the US.

Minimal American representation in Formula 1.

Dataset Used:

Reason 1: Too Many American Grand Prix Disasters.

Formula 1 has utilized 76 tracks in its 72-year history. Some circuits stand the test of time (Monaco, Monza, etc.), while others last for one inglorious year (we’ll discuss these in more detail). And, for whatever reason, Americans excel in crafting short-lived circuits of above-average treachery. When we look at driver did-not-finish (DNF) rates by country, the US stands as a clear leader:

Unsurprisingly, five of the fifteen tracks with the highest recorded DNF rates are US-based. Historically, the average Formula 1 grand prix DNF rate stands at 30%. By comparison, our high-drama courses feature retirement rates above 50%:

The Dallas Grand Prix, which holds the honor of highest DNF rate, boasts this woeful synopsis on its Wikipedia page:

The event was conceived as a way to demonstrate Dallas' status as a "world-class city" and overcame 100 °F (38 °C) heat, a disintegrating track surface and weekend-long rumors of its cancellation...[The course] was bubbling before qualifying, and after a few laps, it began to break apart.

You never want to see the words "bubbling," "disintegrating," and "track surface" near one another. Consequently, the Dallas circuit lasted one year.

And then we have the Sebring International Raceway, which hosted the 1959 United States Grand Prix. The course was built on a former Air Force base and used a mixture of runways and tarmac service roads, which led to large bumps when transitioning between surfaces. The race report recounts:

The bumpy surface of Sebring, particularly where tarmac met concrete, meant that the cars were being given significant punishment. The poor design left seven of eighteen cars in contention with nineteen laps in the race.

Remember, these notable failures are in addition to the 2005 grand prix disaster — so it's a long-running lineage of American catastrophes. And as if the inadequate racing conditions weren't enough, many American Grand Prix events suffered poor attendance and were thus financially disastrous. Moreover, these races spawned a fanship death spiral: one-off races of poor execution that led to inadequate attendance at future races.

Reason 2: No Long-Running F1 American Tradition.

Monte Carlo held the first Monaco Grand Prix on April 14, 1929. The picturesque street circuit quickly became Formula 1's most iconic event. Year after year, F1 devotees and cosmopolitan millionaires invade the small seaside city-state to enjoy trackside yachts and high-intensity street racing. The Monaco Grand Prix is Formula 1 tradition at its finest.

Continuity spawns positive externalities for all members of the Formula 1 ecosystem, as a country's annual grand prix serves as F1's most effective form of localized marketing (i.e. a Hungary-based race will galvanize and grow the Hungarian fan base). So, to what extent has America failed to capture these network effects?

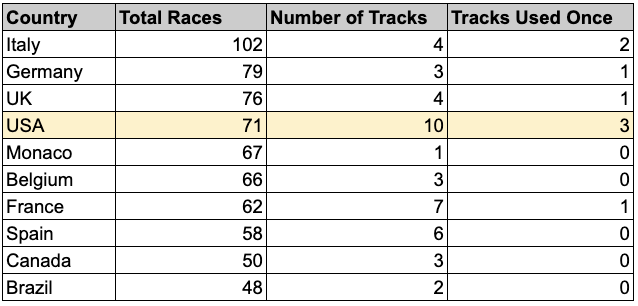

Well, the United States holds the record for most Formula 1 venues since 1950, but that's not a good thing:

Historically, the US has hosted 71 Formula 1 races, a noteworthy triumph given the country’s longstanding circuit struggles. However, this feat has been accomplished across ten tracks (a clear-cut outlier), three of which were one-and-done circuits (also a record). Said otherwise, America's F1 tournament occurs annually, but its discontinuity is an outlier relative to other countries, as the event ping-ponged around the US.

And sure, modern TV syndication may mitigate the deleterious effects of ever-changing grand prix locations, but F1 lacked prominent broadcasting reach before the days of advanced cable and streaming (which constitutes the majority of its history). Thus, attending a nearby grand prix was the sole option for American F1 fans.

And let's say you were lucky enough to score tickets to a grand prix within reasonable travel distance — you may have paid to see a race track disintegrate or Formula 1 drivers protest en masse.

Reason 3: Global Time Difference.

Formula 1 advertises itself as the world's most global sport, and they're right. The 2022 season featured tracks in 21 countries across five continents, which sounds like a logistical nightmare — drivers must exist in a perpetual state of jetlag.

Unfortunately, global reach comes at the expense of temporal continuity, as weekly race times fluctuate wildly. Consider the March 27th and April 9th races from this past season, the first in Saudi Arabia with a start time of 10 am PST and the latter in Australia with a 10 pm PST kickoff.

When we look at the distribution of grand prix start times for the 2022 season, we find a calendar unwelcoming to US audiences:

Americans typically watch sports at night, except for football which commands its own special day. And sure, perhaps east-coasters will stomach a 9 am grand prix, but the timing grows increasingly undesirable as you move westward. Of course, you could tape the race, but a spoiler-laden push notification, text message, or ESPN update can instantaneously ruin your viewing experience.

Reason 4: Oversaturation of Sports Content.

Outside the US, Formula 1 competes with a small set of high-powered leagues in the battle for fan mindshare (English Premier League, La Liga, India's cricket league, etc.). In contrast, American viewership pits Formula 1 against numerous direct rivals like Nascar and IndyCar and a bevy of indirect competition from the NBA, NFL, NHL, MLB, and more.

In mid-2022, motorsports (F1, Nascar, IndyCar) were estimated to be the tenth most-followed sport in the US:

And Formula 1's slice of that pie is even smaller, as the league sits third in American motorsport fanship, roughly even with IndyCar and significantly behind Nascar:

There is only so much time to watch sports, yet content is ever-proliferating. And sure, Drive to Survive may have propelled the league from relative obscurity, but many competing sports organizations are working with Netflix to develop their own docudramas. The ATP and WTA tennis tours released Break Point earlier this year, and the PGA tour is releasing Full Swing on February 15. American sports leagues are desperately searching for their own Drive to Survive bump.

It appears we live in a golden age of sports content — especially for tell-all sports-centric docuseries.

Reason 5: Lack of American F1 Drivers.

In 2002, the Houston Rockets drafted Yao Ming, making him the first Chinese basketball player in NBA history. A 7′ 6″ giant with a goofy personality, Yao became an instant media sensation, ushering the world's largest country into NBA fandom. In Yao's rookie season, the NBA began offering All-Star ballots in Mandarin to globalize voter participation. Despite an up-and-down rookie year, Chinese natives powered Yao to the second-highest vote total (1,286,324) behind only Kobe Bryant (1,474,386).

Since then, the NBA's Chinese business has grown to 500 million fans and accounts for nearly $5 billion in annualized revenues. Unsurprisingly, Yao's illustrious career and cultural ambassadorship receive significant credit for popularizing the NBA in China.

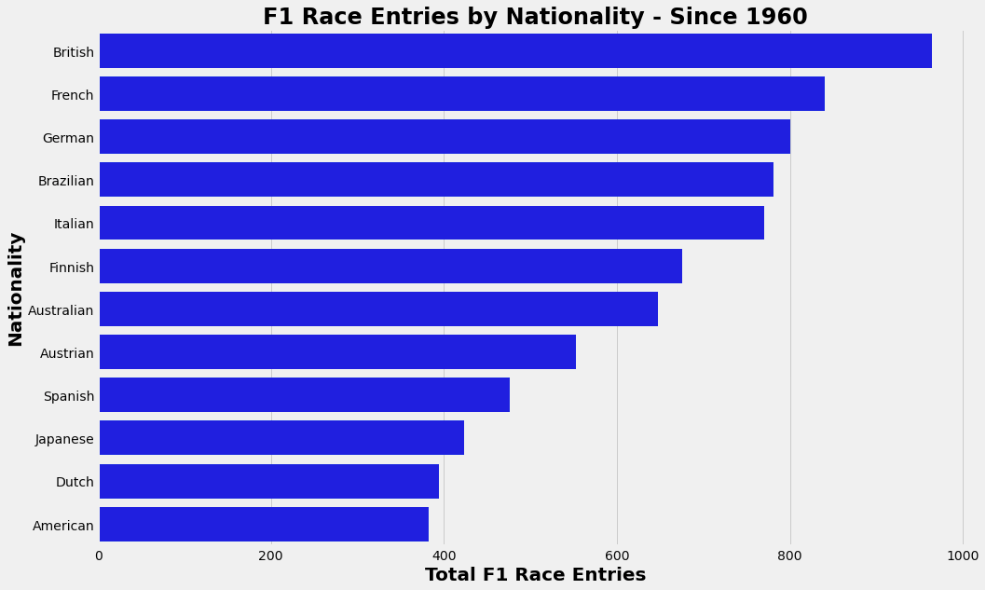

So does the US have such an ambassador in Formula 1? In short, no. There have been 33 American Formula 1 drivers since 1960. During that span, US-born racers competed in 338 races, the twelfth-highest amongst all countries, though disappointing given America’s massive population:

Furthermore, American driver careers are notoriously short, as most F1 entrants occurred in the 60s and 70s when motorists could participate in Formula 1 events on an ad hoc basis. Unfortunately, these short stints yielded poor results, with many careers lasting one to two races. In fact, only 19 American racers have competed in 10 or more contests.

As a result, the average American F1 driver participates in 11 grand prix events — 32 races below the global average and third worst amongst all nations:

So, if you, a curious American, woke up at 6 am PST to follow a Formula 1 race, you were highly unlikely to see a US-born racer, or at least one with meaningful career prospects.

Final Thoughts: Will Formula 1 Cross the Chasm?

In the business school classic Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore argues that product adoption occurs through the phased acquisition of various consumer cohorts:

According to Moore, the most challenging step is transitioning between "visionaries" (early adopters) and "pragmatists" (early majority of users) — this stage represents the titular "chasm." According to Moore, each cohort maintains differing expectations, and thus companies should adjust their product positioning, marketing, and distribution to the needs and expectations of their current acquisition cohort.

So where does Formula 1's courtship of American audiences sit in Moore's framework? Probably somewhere in the chasm.

At present, racing enthusiasts and trendsetters constitute most of F1's American viewership. For those not inherently interested in motorsports, watching Formula 1 carries cultural cache — as if you dug through your grandmother's old things and found a nifty scarf. So here's this complex global sport with a storied history and high net-worth fanbase that Americans have wholly ignored for over seventy years — what fodder for cocktail parties. Drive to Survive has made Formula 1 hip, cultivating a formidable pack of early adopters.

But can the sport cross the chasm? Maybe. There have been productive strides over the last decade — with three US races slated for the 2023 season, an $80M ESPN broadcasting deal, and continued production of Drive to Survive. And yet significant structural issues prevent American viewers from readily embracing Formula 1 — a highly saturated sports market, lack of American F1 racing talent, major time differences, and F1 rule complexities. Bridging the chasm will be difficult.

But before we look too far into the future, let's return to the 2005 American Grand Prix — an indelible disaster to mark fifty years of failed market expansion. So much has changed since “the worst race of all time." F1's US operations no longer trigger spontaneous driver protests, crumbling race tracks, weaponized beer cans, or police dispatches — it's been a remarkable turnaround.

America’s relationship with Formula 1 has come so far in such a short period of time; one can't help but wonder where it will go.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Really interesting analysis. I had no idea the US had been involved so much in F1 at all — and in such disastrous ways. Great read.