Why Do People Like True Crime? A Statistical Analysis

Exploring the appeal of true crime podcasts and docuseries.

Intro: True Crime in Iowa

On June 9th, 1912, eight bodies were discovered at a farmhouse in Villisca, Iowa. The attack victims had been savagely assaulted with an axe, and the crime scene exhibited several curious details, such as a piece of bacon placed beside the abandoned murder weapon and sheets draped over every mirror in the house.

The shocking nature of these murders attracted hundreds of curious onlookers to the Villisca farmhouse, with dozens of bystanders simply entering the crime scene for a self-guided tour. Legend has it that some trespassers took fragments of the victims' bones to save as macabre momentos. Ultimately, the crime scene was heavily contaminated by these intruders, disrupting the investigation and preventing law enforcement from ever catching and convicting the perpetrator.

These events are widely known as "The Villisca Axe Murders," a century-old mystery that now serves as fodder for true crime media (and, I guess, this essay). Today, if you want to learn about the Villisca tragedy, you can listen to accounts of the incident on podcasts like Lore, Morbid, and Wicked and Grim, or watch televised investigations on shows like Ghost Adventures, Scariest Places on Earth, and Most Terrifying Places in America. Who knows, by the time you finish reading this, another episode may have been added to the ever-growing canon of Villisca murder lore.

The roots of modern true crime media can be traced to a 15-month content explosion in 2014 and 2015, which saw the release of Serial, The Jinx, and Making a Murderer. The crossover success of these projects has cemented this once-niche subgenre as a staple of popular culture. Since then, there has been no shortage of true crime content, with podcasters and streaming executives producing an endless parade of real-life mystery media to capture the collective fascination and fear of audiences everywhere.

So today, we'll delve into the motivations and instinctual drives underlying true crime consumption. We'll explore the deep-seated curiosities that attract viewers to these morbid accounts and the primal urges that drove a group of early 20th-century Iowans to invade a crime scene (and allegedly collect souvenirs).

Reason One: Morbid Curiosity and Mystery

Is it ethical for a home security company to publish a report on true crime (that serves as some sort of sales tactic)? I don't know. Does sharing research conducted by this home security company somehow entangle me within the true-crime-industrial-complex? Quite possibly, but I don't care.

In 2023, security company Vivint conducted a sprawling survey on the appeal and effects of true crime media. Vivint surveyed over 1,000 self-identifying true crime fans to understand their affinity for stories of real-life criminality. The most common reasons cited were:

Curiosity: 73% of respondents

Entertainment: 46% of respondents

Mystery: 45% of respondents

My first question about this statistic concerns the 54% of respondents who didn't highlight "entertainment" as a primary motivator, even though podcasts, streaming shows, and documentaries all qualify as entertainment. What is true crime if not entertainment?

My second question concerns the vaguely defined motivations described as "curiosity" and "mystery": What are these instinctual drives, and how has true crime tapped into these urges? The answer lies in a field of study known as "morbid curiosity," which explores humanity's fascination with the perverse and macabre.

Behavioral scientist Coltan Scrivner has dedicated his career to studying the deep-seated impulses underlying the consumption of horror and true crime. If you've ever wondered why people love The Texas Chainsaw Massacre or binge-watched Netflix's Dahmer series, his research is a good starting point.

Scrivner ultimately segments morbid curiosity into four distinct archetypes:

Mind: involves an interest in understanding the psychological aspects of morbid phenomena.

Body: a fascination with the physical aspects of death, injury, and the grotesque.

Supernatural: a desire to explore and understand paranormal occurrences beyond our natural world.

Violence: interest in witnessing or learning about acts of physical aggression and brutality.

Once defining these personas, Scrivner conducted survey research to identify sentiments unique to each form of morbid curiosity. Unsurprisingly, motivations tied to "mind" morbid curiosity are closely linked to characteristics of the true crime genre:

Scrivner further defined these archetypes by quantifying distinct personality traits associated with each pathology. Those demonstrating morbid curiosity of the mind enjoyed "getting in the head" of the disturbed, driven by thrill-seeking, overt social curiosity, and desensitization to "disgusting" stimuli.

True crime series like Making a Murderer and The Jinx tap into our primal fascinations with unusual pathologies. What does John Wayne Gacy dressing up as a clown say about his psychology (and murderous behavior)? How did The Zodiac create his cipher, and why was he intent on communicating with the press? These questions captivate those with a strong sense of morbid curiosity.

But it's more than the presence of the macabre that entices true crime consumption—it's also the narrative intrigue and joys of a good mystery.

A 2024 YouGov survey of 1,000 Americans identified the primary motivations for true crime consumption to be "interest in mystery," "watching cases being solved," and "interest in psychology."

To say there was a string of five unsolved murders in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s is hardly enthralling. But what if these crimes can be attributed to an anonymous serial killer (The Zodiac) who taunts the police and has his own cryptic language? Now that's a fun little mystery.

In fact, the enduring myth of an unsolved murder is a common hallmark of true crime appeal. A 2022 Reddit poll with over 7,500 responses ranked Jack the Ripper and The Zodiac as the top two candidates for "most famous serial killer in history"—in both cases, the identity of these figures will remain forever unknown.

Indeed, there is something profoundly intriguing about the combination of the morbid and the unknowable (especially when presented as a six-episode Netflix docuseries).

Reason Two: The Perceived Societal Good of True Crime

The popularity of modern true crime is heavily indebted to the considerable real-world impact of early breakout hits like Making a Murderer and Serial. Consider the case of Adnan Syed, the subject of Serial's first season. The unprecedented popularity of this podcast led to significant media attention and renewed legal efforts, eventually resulting in Syed's conviction being overturned in 2022. A measly little podcast had single-handedly corrected an injustice.

Cases like the vindication of Adnan Syed, where a high-profile docuseries corrects a miscarriage of justice, have imbued the true crime genre with a heightened sense of importance and urgency. True crime isn't merely entertainment—this content can (conceivably) change lives and serve as a check on the judicial branch.

In both a 2024 YouGov poll and a 2023 Vivint survey, numerous respondents highlighted the real-world utility of true crime when asked about the genre's cultural impact.

In many ways, the perceived societal importance of true crime mirrors that of news media. Watching MSNBC or Fox News is often associated with a sense of civic duty and a desire "to be informed." This may explain why 54% of true crime fans in the Vivint survey do not view the genre as "entertainment."

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Reason Three: The Unique Gender Dynamics Behind True Crime's Popularity

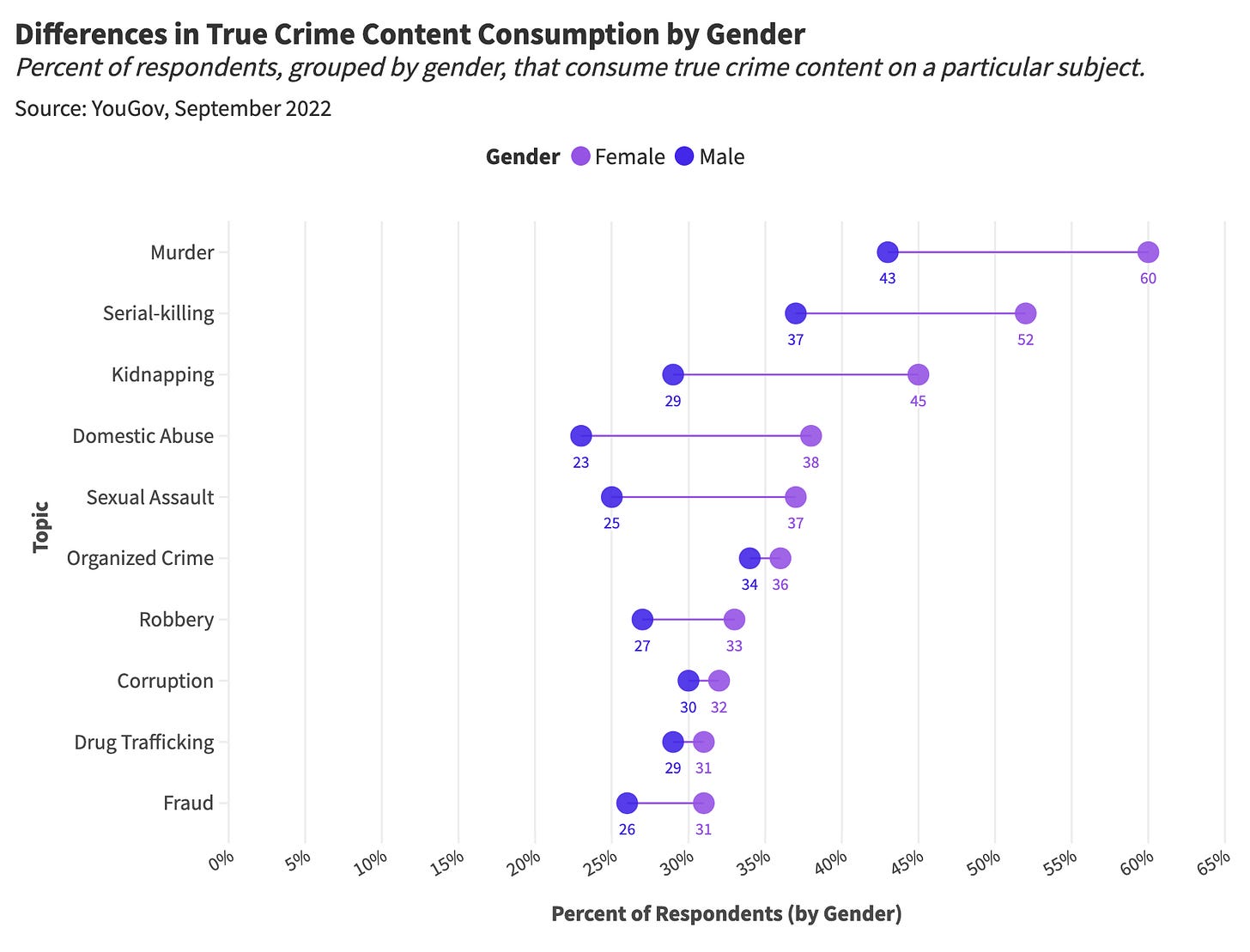

Numerous true crime studies find the genre to be overwhelmingly popular amongst women. A 2022 YouGov survey found that women were significantly more likely than men to consume crime-oriented podcasts and docuseries, demonstrating heightened interest across all types of criminal acts (which is a weird way to segment content).

Inevitably, this begs the question of why: what makes these stories more appealing to female audiences?

To better understand the genre's appeal amongst women, researchers at The University of Illinois adjusted the marketing message of various crime books and asked participants to choose between reading options emphasizing distinct characteristics. Ultimately, women were more likely to select stories that advertised escape tactics, delved into a killer's psychology, and had a female victim.

Rather than draw sweeping conclusions from this research, I'm left with a series of questions:

Do people identify with the victims depicted in these stories (to the point where they seek out the content)?

Are viewers utilizing this media as a form of vicarious preparation?

Why do numerous survey respondents cite true crime as a motivating factor for increased "vigilance" and "safety consciousness?"

This collection of data points reinforces the idea that true crime offers perceived value beyond entertainment. These same curiosities and anxieties might also explain why a home security company would publish true crime research (to promote their product indirectly).

Reason Four: The Marriage of Mass Media and True Crime

Those who enjoy true crime consume this content with great frequency. A 2024 YouGov poll found that 30% of Americans engage with true crime content every week, and 41% engage with crime-oriented content every month.

That's remarkable engagement for a streaming property or podcast, especially considering the low production costs associated with this type of programming (compared to, say, Masters of the Air and its $250M price tag).

And where do people consume true crime? On Netflix and YouTube, mostly—though we find some degree of consumption across every major streaming service and digital platform.

In response, streamers have doubled down on nonfiction crime content, padding their libraries with documentaries and docuseries about real-life criminality (with the exception of Disney+, which caters to children).

The genre's supply and demand dynamics seem to exist in a virtuous cycle—the more true crime content is produced, the more demand increases. Perhaps the genre will just expand infinitely, avoiding cultural overexposure and backlash reminiscent of "Marvel superhero fatigue" and "Star Wars exhaustion." Maybe there is no limit to an economic opportunity fueled by morbid curiosity.

Final Thoughts: 50 Years of Morbid Curiosity

A recent cover of People Magazine celebrated "50 Years of True Crime Stories," adorned with pictures of the genre's most renowned figures—JonBenét Ramsey, Gypsy Rose Blanchard, Elizabeth Smart, and (somewhat surprisingly) Tupac. One interpretation of this magazine cover frames true crime as a recent phenomenon—that these captivating stories didn't exist before the early 1980s.

Obviously, this is not true. People have been getting murdered in sensational ways for centuries, and these stories have always generated exceptional news coverage and public interest. What's novel about the last "50 years of true crime stories" is how these tales have been adapted and embraced by fledgling media formats—initially championed by cable TV, then the 24-hour news cycles, then tabloid journalism, then social media, then podcasts, and, eventually, achieving their final form as a six-part streaming docuseries. With each shift in entertainment media, true crime has become increasingly entrenched in mainstream culture, continuously recalibrated to be more compelling (and addictive).

Through trial and error, content creators have come to understand our inherent fascination with morbidity and have tailored their stories to satisfy these primal urges. These networks, streamers, and podcast studios satisfy our primordial fascinations with mystery and the macabre—the very impulses that spawned mass trespassing at the Villisca farmhouse crime scene.

The true crime genre has evolved into a standardized commodity, employing a systematic approach to depictions of real-life tragedy. And guess what? We love it; the more sensational, the better. And it's nobody's fault because they're just giving us what we want. At least now, nobody has to sully a farmhouse crime scene to get their fix.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

I asked my wife, who watches true crime content on a seemingly daily basis, why she likes it. At first the best she could say is that it's interesting, but then she said there was something about it having really happened that appeals to her. When I asked why she doesn't watch documentaries about other exciting things that happened, she was again unsure.

She said it may be in part because historical documentaries are too similar to what you had to learn in school, whereas true crime is more lurid, and something that isn't taught, so there's no "doing homework" feeling to it. She also mentioned that she tends to avoid the older, "true crime from the 1800s!" content, and gravitates towards modern crimes.

She also said she especially likes the "wife kills husband" stories, but I didn't press her for thoughts on why that's the case.

As some who has gone through spells over the last ten years of listening to every true crime podcast under the sun - the gnarlier the better - I think it comes down to some strange comfort in knowing just how low humanity can go. Maybe comfort is the wrong word, it's hard to put a finger on.