Why Do People Like Horror Films? A Statistical Analysis

Exploring the unique appeal of scary movies.

Intro: Why Would People Watch This?

My wife and I recently watched Denis Villeneuve's Prisoners, a visceral, often gory, thriller that could best be described as a nihilistic nail-biter with some horror elements. The film tells the story of two young girls who are abducted in broad daylight and the frenzied (and quite violent) efforts undertaken to rescue them.

We decided to watch this film based on several glowing recommendations:

One friend said it was their all-time favorite movie.

A recommender hailed Prisoners as one of the best thrillers in recent memory.

One family member took comfort in the film and had watched it three times.

My wife was excited: would this be a joyous thrill ride like The Fugitive or The Town?

And here is where Prisoners' "horror elements" come into play; the movie is a 2.5-hour tension-fest marked by carnage, home invasions, violent abductions, and the abuse of minors. I love this film, though I must stress that it is a doozy.

Caught off guard by this unrelenting three-hour nightmare, my wife eventually asked to turn the film off. And let me tell you, she was pissed. But she wasn't pissed at the movie; rather, she was baffled by those who had recommended the movie.

"Why do people like this?" she kept repeating to herself. "How could someone watch this multiple times?"

Her frustrations got me thinking about the nature of horror fandom. Sure, Prisoners is not a true horror movie, but what causes people to gravitate toward disturbing content (like Prisoners)? Why do people like horror?

So today, we'll investigate the rise of horror films, the distinctive motivations behind horror fandom, and the types of people who cherish these movies.

The Rise of A Divisive Genre

In 1932, Tod Browning's Freaks was met with unrivaled disgust, receiving arguably the worst audience reaction of any movie to date. Freaks tells the story of a conniving trapeze artist who joins a group of carnival sideshow performers in order to seduce and murder a dwarf within the troupe. The production employed several carnival performers with real-life disabilities, a casting coup that shocked moviegoers of the 1930s, especially when the so-called "freaks" enact their revenge in the film's final act.

The reactions to this film could best be described as "bonkers":

During the movie's initial screening, there were reports of audience members fainting and screaming, with nearly half of attendees "sprinting" to the exits.

A woman claimed to have suffered a miscarriage after watching the film, allegedly due to the shock—she would later sue MGM and the filmmaker.

Freaks was banned in the UK, even after the studio removed 30 minutes from the film's 90-minute runtime. MGM eventually pulled Freaks out of circulation entirely.

Ultimately, Freaks was ahead of its time—and would later be rediscovered—a horror classic that arrived well before the genre rose to mainstream prominence in the 1980s. In many ways, the Freaks debacle is a microcosm of horror's unique status within the film landscape, a distinctive storytelling format capable of generating both revulsion and excitement.

Unsurprisingly, a 2022 YouGov poll of 1,000 Americans found horror to be the most divisive movie genre by a significant margin—garnering a unique mixture of love and hatred from respondents.

And yet, despite this pronounced animosity, horror films have come to represent a sizable share of Hollywood productions, while Westerns, Musicals, and War movies have largely faded away.

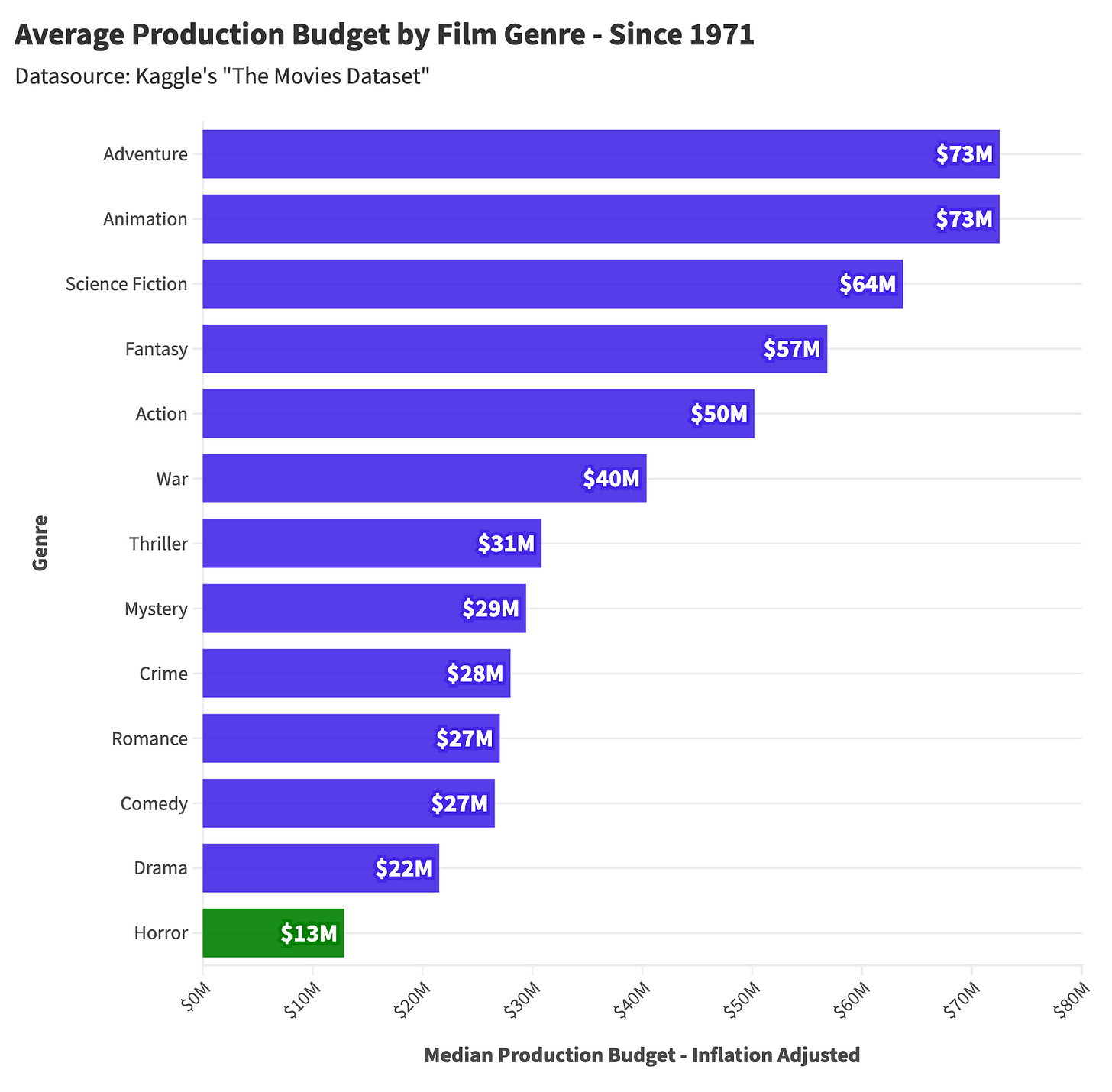

Horror movies command significantly smaller budgets than the average film, with adventure, Sci-Fi, and animation projects typically receiving five times the funding of scary movies. As such, horror films don't have to achieve blockbuster grosses to turn a profit.

Better still, when it comes to scary movies, there is little correlation between a project's critical acclaim and box office performance. Horror films come with a loyal built-in audience, much like superhero franchises or Star Wars spin-offs—this fandom will reliably show up to theaters, often agnostic of quality. When we bucket movies by average user review, sorting films into quality quartiles, horror flicks enjoy strong returns for low-scoring projects and outstanding returns for acclaimed works—significantly outperforming other genres.

A bad horror movie makes for a good investment, while a decent drama will likely lose money for its producers.

Scary movies are one of the few “sure things” in a film industry marked by ever-declining ticket sales—a phenomenon largely driven by the genre’s unique fanbase. At the same time, this fact begs a deeper question: what makes someone a horror fan? What does it mean to love this distinct and highly divisive genre?

Why Do People Love Horror Films?

2022's Skinamarink is one of the most divisive movies of the 21st century. A micro-budget box office success, Skinamarink is a slow-moving atmospheric nightmare about two children waking up in the middle of the night to find their father missing and all the windows and doors of their house vanished. Some people hail this movie as a masterful exercise in lo-fi dread, while others consider this the worst moviegoing experience of their life, with virtually no middle ground.

Ultimately, the buzz surrounding Skinamarink propelled the project to $2.1M in ticket sales against a $15k budget (for a 13,900% return on investment). And while Skinamarink is a dramatic example of horror's polarizing effect, it's an apt window into moviegoer bifurcation—people either love or hate this genre.

Scientists have discovered substantial differences in how various personality types process scary movies. In one study, researchers tracked how "fear-avoidant" and "fear-approaching" personalities felt before and after a horror film. Both fear-avoiders and fear-approachers saw an equal uptick in negative emotions as a result of their exposure to a disturbing movie.

Yet only the fear-approaching group saw a rise in positive sentiment following their scary movie experience.

Those predisposed to horror (the fear-approaching) experience fear like everyone else, but they internalize this sensation differently. A positive reaction to a scary movie occurs when that film stimulates a viewer's optimal fear threshold (which, for some, is no fear).

In a 2022 study of haunted house attendees, researchers found an inverted U-shape relationship between fear and enjoyment—illuminating a so-called "fear sweet spot" for fright-seekers.

You can envision fear-approachers easily dwelling within this sweet spot and fear-avoiders sitting at the far ends of this spectrum. This relationship matches my own experiences with the horror genre:

Not Scared Enough: A few years ago, I watched Evil Dead 2, a horror classic, and I was both not scared and not entertained. Apologies to those who love this film.

Too Scared: When I was 13, I watched The Grudge and couldn't sleep for three days. I found this experience to be equally unenjoyable.

This Goldilocks conundrum has defined my relationship with scary movies: I am either too scared or not scared enough. I am what scientists have termed a "white knuckler," a persona averse to fear exposure.

University of Chicago researcher Coltan Scrivner, a leading expert on the science of horror, true crime, and morbid curiosity, has conducted extensive research on the appeal of horror, finding that viewers mostly fit into three distinct groups: adrenaline junkies, white knucklers, and dark copers.

Adrenaline Junkie: Adrenaline junkies desire novel, complex, and intense experiences. Adrenaline junkies tend to upregulate their arousal by immersing themselves more in the experience.

The White Knuckler: White Knucklers are genuinely afraid of scary movies and do not necessarily enjoy the suspenseful aspects of these films. Unlike adrenaline junkies, who try to maximize their arousal, white knucklers tend to downregulate.

The Dark Coper: This group uses horror to cope with various aspects of their lives. Many dark copers report using scary movies to deal with feelings of anxiety.

Scrivner and his team sorted research participants into these groups and then asked them why they enjoyed horror movies. The results indicated unique motivations and takeaways for each fan typology.

Scrivner's research also found that these archetypes uniquely process and contextualize these scary experiences, with some reporting mood improvements while others felt a sense of self-discovery or self-learning.

Adrenaline junkies derive a mood boost from fear-inducing experiences, while white knucklers rationalize these occasions as an opportunity for personal growth and learning. Dark copers find meaning in fright for a wide range of reasons—a testament to this bizarrely nebulous persona. I can safely say that I do not qualify as a dark coper.

Ultimately, horror fandom is not defined by a single personality type. Instead, the genre appeals to numerous cohorts, each with a distinctive relationship to this storytelling format.

As I dug into the research on white knucklers and dark copers, I couldn't help but wonder what brings someone to this point. How does one become an adrenaline junkie? What factors draw someone into the horror genre and lend themselves to these typologies?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Who Likes Horror Movies?

There are a handful of movie genres with strong associations to a single audience demographic. Romantic comedies often skew toward female audiences, while action may best appeal to male viewers. And then there's horror, a genre whose audience cannot be encapsulated through a pithy observation. My logic for horror fandom has always been circular: horror fans love horror movies (quite profound, I know). So who are these devotees?

A 2022 YouGov survey of 1,000 Americans asked respondents to indicate whether they "loved," "liked," or "hated" scary movies and then analyzed these responses across various demographics. Looking at the cohorts with the highest "love" rates, we find disproportionately high approval from those with a high school degree or less and viewers in the 30- to 44-year-old age range.

Truthfully, I always thought horror skewed younger, so these findings are somewhat surprising. Perhaps scary movies are a preferred escape from early adulthood and the perils of middle age (though that's just my best guess). The association with education tracks, so far as film snobs are openly contemptuous of the genre. Well, guess what, film snobs—if you want to keep seeing original stories in theaters you may want to change your opinion. Horror is here to stay; other genres and budget ranges are slowly dying.

Demographical information is a good starting point for parsing horror fandom, though it's ultimately a crude heuristic—people are more than their age, education, and gender (you heard it here first!). What personality traits draw someone to horror? Do people develop an affinity for the genre through exposure, or is this preference part of their nature?

A 2020 study by UPenn and Cambridge researchers explored the association between the Big Five personality traits and genre selection, analyzing how these characteristics correlate with story preference. Those who indexed heavily on neuroticism were likelier to consume scary movies, while other traits were associated with lower levels of horror viewership.

It was at this point that I became confused. Wouldn't someone who skews "neurotic" want to avoid frights and torments? Wouldn't this person be better off watching Sleepless in Seattle or Dazed and Confused on a loop? Surely, this finding had to be a mistake.

But, alas, I was wrong, as this association has been replicated across numerous analyses. A 2007 study explored the relationship between consumer mood and video store selections, identifying significant correlations between certain mindsets and genre choice. Researchers found that those who identified as "nervous" were more likely to select a horror film.

Further qualitative research indicates that individuals with heightened anxiety may gravitate toward horror films as a way of confronting and controlling their fear in a safe environment. Coltan Scrivener and his colleagues at the University of Chicago suggest that horror fans often exhibit greater psychological resilience during times of stress, possibly due to their engagement with fictional threats as a means of preparation (even if this "preparation" is unintentional).

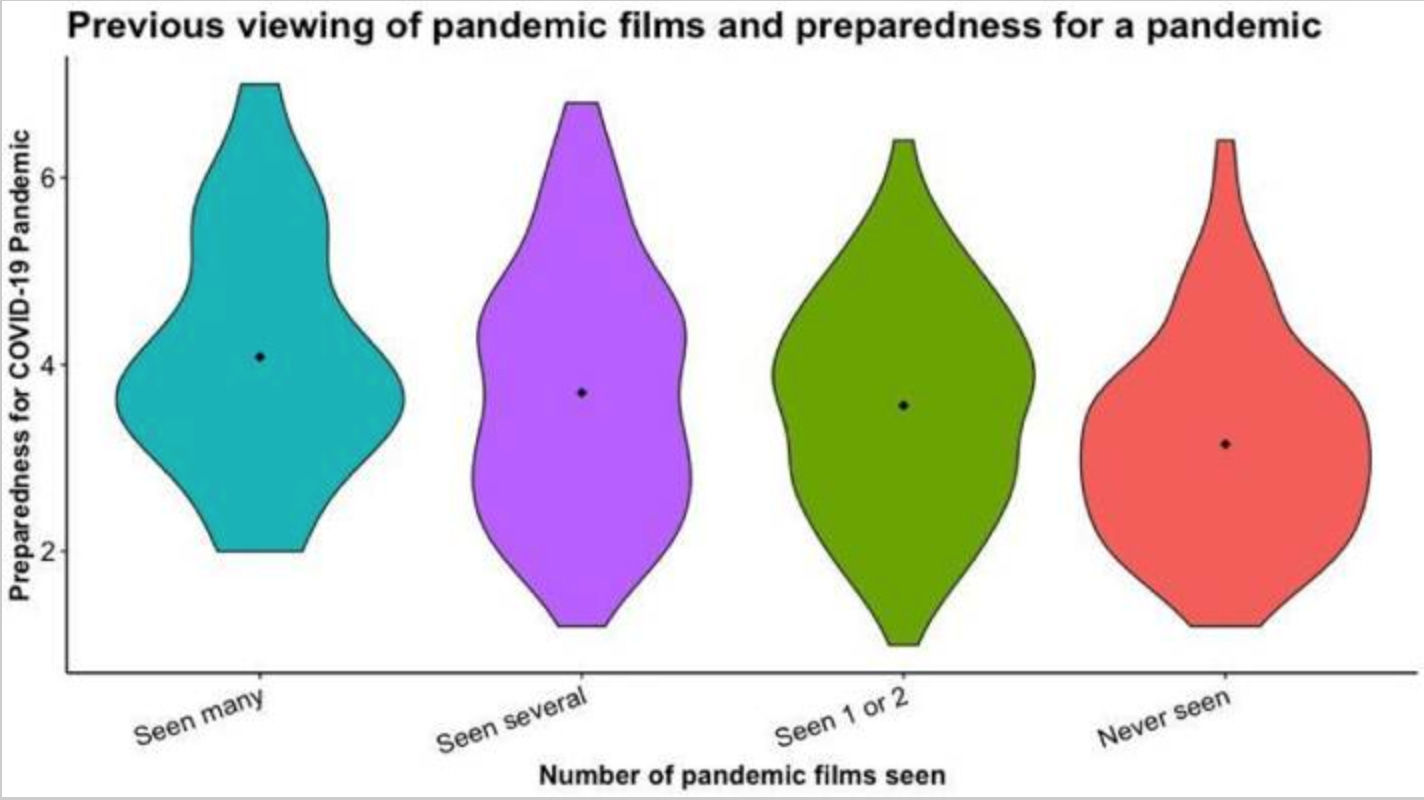

A 2020 analysis by Scrivner and Aarhus University's Recreational Fear Lab found a strong link between a subject's horror fandom and their ability to cope with the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who identified as consumers of horror films or demonstrated "morbid curiosity" had higher levels of positive resilience and preparedness in tandem with low levels of psychological distress.

The study also found a positive relationship between the quantity of pandemic-oriented content consumed pre-COVID-19 and a participant's mental preparedness.

These people were inadvertently training themselves for a global catastrophe, growing their resilience through repeat viewings of Saw II, Contagion, and Hereditary. Meanwhile, I was watching Lady Bird and Call Me By Your Name, reveling in coming-of-age angst and nuanced dramatic tension. Needless to say, I would score quite low for any marker of pandemic preparedness.

Sure, there is an empirical utility to deliberate fear exposure, but that doesn't mean I can change my content preferences overnight. I simply never enjoyed horror movies and continue to have a bad time whenever I return to the genre. Is one’s affinity for fright a function of nature or nurture? When and how do people cultivate their relationship with the genre?

YouGov polling indicates that those with horror-loving parents are three times more likely to enjoy the genre, while those with horror-loving partners are twice as likely to consume scary movies.

Maybe someone's desire for fright stems from biology, or perhaps this preference is passed down through family rituals, with sons and daughters re-watching Halloween and Scream with their parents. Most likely, it's a combination of the two, a characteristic perpetuated through tradition and genetics.

While other families were bonding over horror films like Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street, my dad and I were watching Field of Dreams for the fifth time, silently weeping—a pastime that (once again) did little to prepare me for the pandemic.

Final Thoughts: Dreams of Horror Fandom

When I was twelve, I made the mistake of watching The Ring. For those who haven't seen The Ring, consider yourself lucky because this movie is absolutely terrifying. The basic premise involves a killer videotape that, if watched, will lead to your grisly death precisely seven days later. I was both frightened by the visceral experience of watching this movie and then tormented by the prospect of dying seven days after its viewing.

For six days after watching The Ring, I couldn't sleep and frequently woke up to check for murderous ghosts and ghouls. If this sounds a bit melodramatic, that's because it was—I was twelve years old and unconditioned to scary movies. On my seventh day post-Ring I made my mom sit beside me all night, convinced she would protect me from videotape-induced-death.

Alas, I did not die, but the experience left me scarred. Did a single two-hour movie just ruin seven days of my life (seven days I would never be able to get back)? It was at this moment that I swore off the horror genre. Never again would I request babysitting from my own parents—this genre was dead to me.

And yet, years later, I wish I had responded differently to this experience—I wish I enjoyed horror movies. Horror is one of the few exceptions to a modern film landscape devoid of original storytelling and cinematic experimentation. This genre commands multiple standalone streaming services and film festivals, and there are indie studios like A24 and Blumhouse that dedicate more than 50% of their production slate to horror concepts. Unfortunately, this inspiring creative output is irrelevant to me because I am a white knuckler whose parents dislike horror films. Perhaps I can actively cultivate an appreciation for the genre—a 31-year-old fear-avoider who defied the odds to develop a fondness for movies like Scream VI and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. What a success story that would be.

If you like the horror genre, congratulations—you can continue frequenting theaters whilst forging a meaningful bond with the content you consume (be it a cathartic release or a pleasant adrenaline spike). Meanwhile, I'll be stuck watching premium mediocre retread like Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire, trying to convince myself that I had a great time at the movies.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

Dark copers of the world... watch The Invisible Man, with Elizabeth Moss. Last movie I watched in a theater before lockdown began, wouldn't have had it any other way -- for statistically valid reasons, I now know!

Just read this with interest. I have loved horror films for as long as I can remember. I definitely fit the adrenaline junkie category and am definitely not neurotic. I wouldn’t say I was particularly exposed to the genre growing up although I guess my dad did watch some horror and I was aware of that in a peripheral sort of way so maybe that had an effect. My daughter also loves horror but I think she is more of a dark coper. We also both love disaster movies and I wonder if the two genres fulfil the same need.