Why Do People Hate Nickelback So Much? A Statistical Analysis.

Fact-checking an internet phenomenon.

Intro: People Do Not Like Nickelback.

How does one explain Nickelback? And how does one explain the band's remarkable second life as a meme? Well, for starters, Nickelback is a post-grunge Canadian rock band that enjoyed great commercial success during the 2000s and is often on the receiving end of substantial internet hostility. The band has sold over 50 million albums worldwide, making them the 101st most successful music act of all time. And yet, hatred abounds.

In 2012, Buzzfeed ranked the band's hit single "Rockstar" as #2 on their list of "30 Of The Worst Songs Ever Written" (a quality piece of journalism). In 2013, Rolling Stone readers voted Nickelback the second worst band of the 90s (after Creed). And in 2019, Variety ran an article claiming that Imagine Dragons had finally supplanted Nickelback as the worst band of all time (as if there is some long-running scoreboard).

Sure, the media dislikes Nickelback, but such hatred is confined to the digital realm, right? Not so. On November 3, 2011, the NFL announced the Canadian group as its marquee act for the league's Thanksgiving halftime show. NFL viewers were displeased, particularly Detroit fans forced to watch the show live. Frustrated Michiganders quickly drafted an online petition to replace Nickelback. From the petition:

This game is nationally televised, do we really want the rest of the US to associate Detroit with Nickelback? Detroit is home to so many great musicians and they chose Nickelback?!?!?! Does anyone even like Nickelback?

The petition obtained 55,199 signatures but failed to prevent a lukewarm Nickelback halftime performance. The show went on as the band's set saw widespread boos cascading throughout the stadium. Nickelback hatred had spread to the physical world.

Since then, the myth of Nickelback's awfulness has only grown through gifs, worst-of polls, clickbait articles, comedian punchlines, youtube mashups, and every other conceivable internet medium. But why is Nickelback the internet's punching bag of choice, and what led to such a high degree of collective animosity? Is there a quantifiable explanation for all of this Nickelback hatred?

Hypothesis 1: Nickelback is Overplayed.

What does it mean to be overplayed? In theory, music consumption should function like any market — the public's desire to hear a music act (demand) dictates the prevalence of that music act (supply). So, in the case of Nickelback, what explains the perceived disequilibrium of supply and demand?

Overexposure, or at least widespread claims of overexposure, likely results from a gap between acclaim (critical or consumer) and commercial success. Album sales typically inform public syndication (radio, bars, clubs, etc.), making the music unavoidable, while praise (from a large contingent or a handful of elites) monopolizes internet discourse, thus propagating critiques of these unavoidable songs.

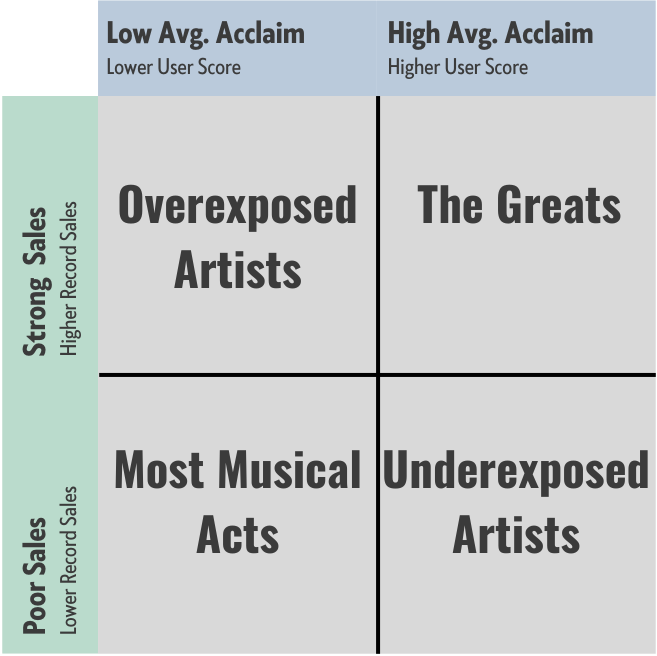

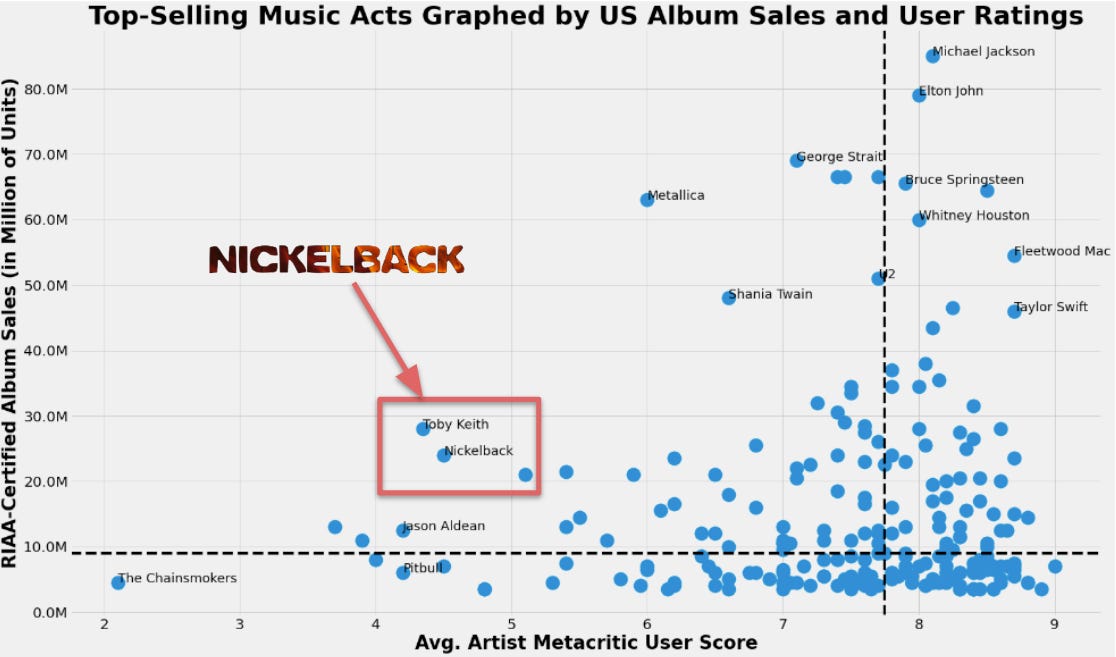

Our analysis will utilize US-based album sales as a proxy for commercial success and Metacritic user ratings as a marker of consumer acclaim. The resulting combination of factors produces a two-by-two grid of critical and commercial acclaim:

When we graph artists above 3M in album sales, Nickelback stands as a clear-cut outlier in the "overexposure" quadrant, along with several marquee country music acts:

Nickelback's low user scoring doesn't mean they are universally despised — unless an army of Russian bots is responsible for +20M in album sales. Instead, there is likely a sizable contingent of vigilant music consumers who strongly disapprove of Nickelback and cannot evade their songs.

That said, Nickelback's status as overplayed may be a relic of music's pre-streaming era. In the 90s and 2000s, music videos and radio served as the preeminent media formats for music discovery. Music publishers largely controlled these mediums, monopolizing airtime to steer consumers toward their desired acts (like Creed or Nickelback).

Spotify and streaming would eventually disrupt music distribution as consumers gained control over their discovery experience. Suddenly, music lovers could indulge in niche genres, curate a playlist, and avoid an undesirable artist, free from the tyranny of industry marketing and a potential Nickelback successor.

Hypothesis 2: Nickelback Music is Repetitive.

In 2017, Karl Puschmann of the New Zealand Herald listened to all 89 Nickelback songs to better comprehend the band's unique reputation. In recapping his project, Puschman highlights Nickelback's repetitiveness as a critical feature of the band's distinctive "sonic torture”:

“Having now listened to every one of their songs - including the new one - I can authoritatively state that Nickelback have 89 different titles for three songs. Predominantly they stick to a mid-tempo rock chug that they occasionally speed up or slow down.”

Puschman isn't alone in this opinion, as numerous youtube videos delight in layering Nickelback songs atop one another to highlight the band's repetitiveness. But many artists utilize a signature sound throughout their discography, so is Nickelback special in its lack of variety?

I utilized Spotify's music attribute dataset to investigate composition uniformity across Nickelback's 18 hit songs. Spotify parses audio features like tempo, loudness, key, and danceability from every track on its platform. Using this data, we'll calculate variance across an artist's catalog of hits for each of Spotify's 13 attributes and then rank musicians by average variance.

For example, consider a set of three artists, Bruce Springsteen, Abba, and Katy Perry, where we compare variance for song energy and danceability:

When we run this analysis on artists with 10+ Billboard hits and utilize Spotify’s entire feature set, we find Nickelback within the top 10 of low-variability music acts, falling just behind a handful of country music stars (a polarizing genre in its own right):

We can then graph our variability rankings against record sales, similar to the two-by-two approach used for critical acclaim:

Unsurprisingly, Nickelback places in the high-sales, low-variability quadrant:

Does this mean Bruce Springsteen and Fleetwood Mac (also high sales, low variability) should receive universal scorn? No. Instead, the combination of ubiquity and uniformity would exacerbate existing frustrations with an artist's music. So, if someone is predisposed to dislike Nickelback, Springsteen, or George Strait, then heavily-played songs of similar composition will increasingly enrage that listener. Consider it more fuel in a growing fire of Nickelback animosity.

Hypothesis 3: Liberal Bias May Contribute to Nickelback Bashing.

I did not set out to write an article about identity politics or the US culture wars; I just wanted to write about a band with a terrible reputation. And yet here we are.

A question continually plagued me as I traversed the deep recesses of Nickelback internet hatred: sure, the band is repetitive, and a large digital population expresses extreme hostility toward their songs, but who is buying these albums? What explains the enormous gap between fantastic record sales and hyper-critical media coverage? Unfortunately, geopolitics may play a role.

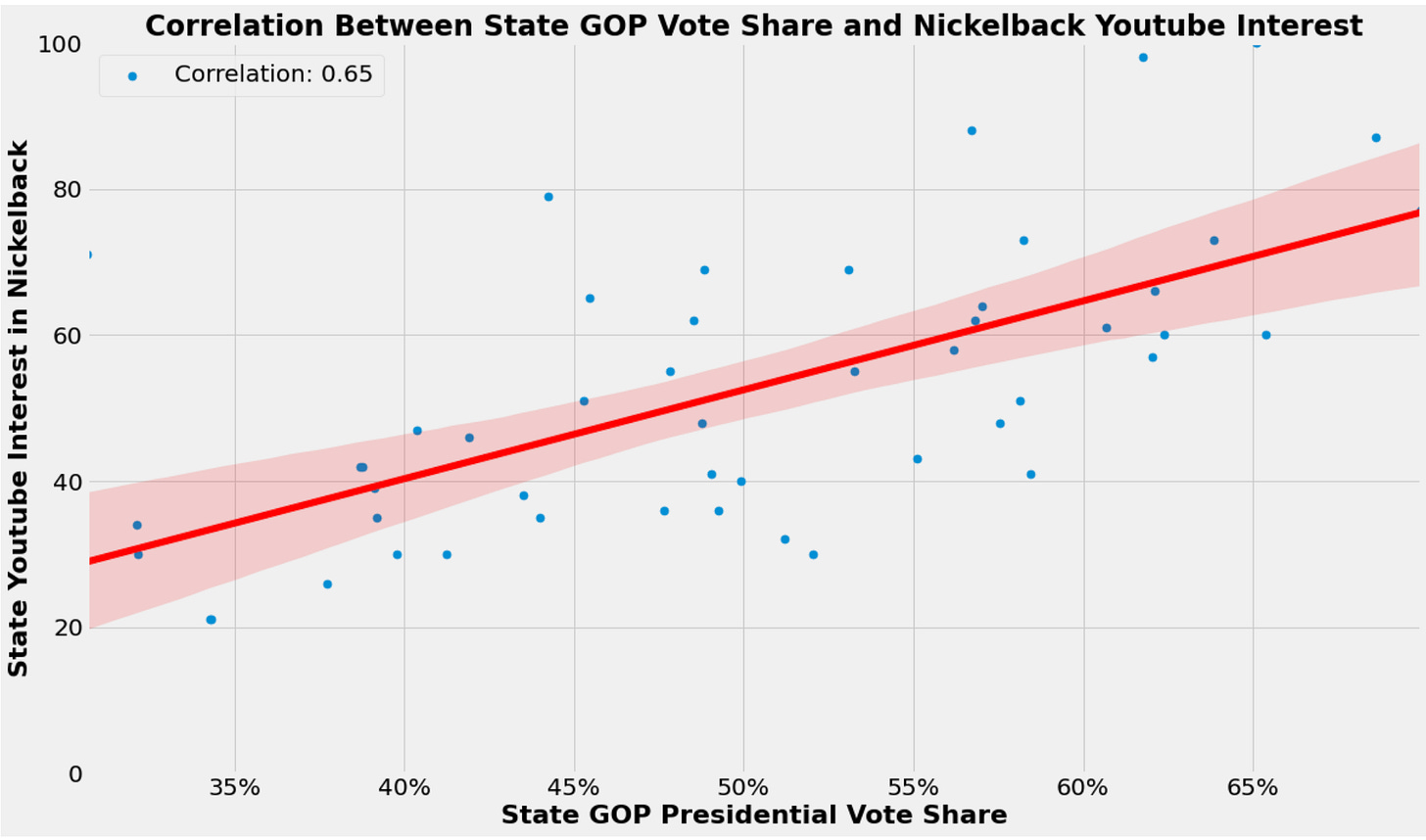

While investigating Nickelback google search data, I noticed a pattern in the band's youtube search interest — query volume ranks highest in right-leaning states:

When we graph our youtube search data against state GOP vote share from the 2020 presidential election, we find a strong correlation between Nickelback interest and Republican voter margin:

Does this mean Nickelback is the victim of a leftist plot to blackball their music? Doubtful — that would take a lot of organization for no gain or discernible purpose. More likely, Nickelback may be less appealing to liberals who happen to dominate prominent news outlets.

The band is consistently labeled post-grunge with a tinge of country music influence, and all our previously investigated metrics group Nickelback amongst country music stars like George Strait, Luke Bryan, and Jason Aldean. So maybe this Canadian rock band somehow elicits the allure (and polarizing effects) of country music while operating under the banner of grunge? If true, that's a highly nuanced form of commercial appeal for a band accused of overwhelming simplicity.

Hypothesis 4: Nickelback Is The Victim of Unlucky Publicity.

Nickelback consistently receives unenviable publicity originating from events outside their control. One such episode involves a once-ubiquitous TV advertisement for a long-forgotten comedy show.

Tough Crowd With Colin Quinn premiered on Comedy Central in late 2002. The program featured a panel of guest comedians discussing current affairs. On a now-infamous episode, the Tough Crowd panel examined a study linking popular music and violence, to which comedian Brian Posehn joked: "No one talks about the studies which show that bad music makes people violent. Like, Nickelback makes me wanna kill Nickelback."

The quip was not particularly memorable, but Comedy Central included the joke in a long-running advertisement for Tough Crowd. And this promo ran a lot.

In a 2022 interview, Nickelback frontman Chad Kroeger pinpointed the Colin Quinn ad as a turning point for the band's reputation:

"They took [that joke], they put it in a commercial for that one show. And that played on Comedy Central for six months straight, this Nickelback joke. That starts this whole thing going. That's where it really started, at that one moment."

To understand the scale of the Tough Crowd ad, I sized the promo's potential audience exposure over the entirety of its run. We can produce an estimate of viewer impressions by combining assumptions of Comedy Central viewership, promo airings per day, and length of the promotional campaign:

There is no data source for daily ad frequency or campaign length; as such, we can craft a sensitivity chart based on a range of outcomes:

According to our calculations, the Tough Crowd ad could have generated anywhere between 1,086,233,379 and 4,344,933,514 impressions, assuming a six to twelve-month run and 12 to 24 airings a day. I guess one well-marketed joke can do serious damage.

But the Colin Quinn promo was one of many incidents of wide-reaching negative publicity. Examining search queries for "Nickelback Hate," we find the term exploded into the zeitgeist in late 2011:

According to Google data, November 2011 serves as a tipping point for Nickelback hostility, with minimal internet traffic before this period and a constant stream of searches following this time. So what happened? Well, the Detroit Lions Thanksgiving halftime show is what happened.

Perhaps this event formalized disparate or long-dormant Nickelback grievances. Suddenly, it was fashionable to dunk on Nickelback. All the long-running frustrations — the overplayed music, the repetitiveness, the cultural divide, some unique priming from a Comedy Central commercial — crystallized in a highly-public spectacle of Nickelback bashing. The Nickelback meme had gone mainstream.

Final Thoughts: Nickelback, The Meme.

Biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term "meme" in his 1976 bestseller The Selfish Gene. Dawkins describes a meme as something that "conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation." Dawkins would further elaborate on his meme construct by framing the spread of cultural beliefs in Darwinian terms:

"Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain, via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation."

According to Dawkins, ideas replicate and spread in a process reminiscent of natural selection. Some ideas take root and survive, while others lose mind share over time. So what explains the longevity of Nickelback as a meme? Nickelback's commercial career peaked in the late 2000s, yet their cultural relevance has grown over time.

Nickelback's mimetic staying power doesn't arise from any one idea but rather an amalgamation of spirited grievances. The band is a Rorschach test for everything you find wrong with modern music — you see what you want to dislike.

To some, Nickelback signifies the pitfalls of over-commercialized music or a diluted capitalistic rendering of Kurt Cobain's once-promising grunge movement. To some, Nickelback's success stems from those on the opposite end of a geopolitical divide. And to some, Nickelback is simply internet shorthand for bad.

Nickelback is an incredibly successful idea — at the expense of the band itself.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

The graph for Hypothesis 3 seems to be largely a function of the fact that Nickelback is from Alberta, and is popular in nearby states.