Why Do People Hate Creed So Much? A Statistical Analysis

How did Creed become "The World's Most Hated Band"?

Intro: Cultural Shorthand for "Bad"

To some, Creed is a widely-known post-grunge band whose early-2000s hits like "Higher" and "One Last Breath" dominated rock radio. To many, however, Creed is cultural shorthand for a widely-known thing that everyone apparently dislikes.

Yet things weren't always so bad for Creed:

Formed in Tallahassee, Florida, in 1994, Creed scored their first Billboard hit five years later with "Higher," an omnipresent and vaguely spiritual earworm. The band would grace the Hot 100 four more times, including a number one single in 2000 with "Arms Wide Open."

In 2001, Creed reached their cultural apex with a nationally televised NFL halftime performance on Thanksgiving Day. Mere months after 9/11, the broadcast intercut footage of first responders at Ground Zero while frontman Scott Stapp sang "My Sacrifice." Today, the band sells t-shirts commemorating "The Greatest Halftime Show Ever," complete with an animated rendering of Stapp sporting angel wings. The vague implication here is that Creed was integral to the nation's post-9/11 healing. I am too young to say otherwise.

And then things started to go downhill for the band:

In 2003, disgruntled Creed fans filed a class-action lawsuit against the group following a disastrous performance where an intoxicated Scott Stapp repeatedly left the stage and slurred his lyrics beyond comprehension. A year later, Creed disbanded, citing tensions between Stapp and the other members.

In 2013, Creed topped a Rolling Stone readers' poll as the worst band of the 1990s, a result frequently cited as definitive proof of cultural inferiority.

In 2024, the band announced their much-anticipated "Summer of '99" reunion tour. A few months later, my friend Zach decided it would be fun to plan his bachelor party around a Creed performance, and so I boarded a four-hour flight to New Orleans to see a band Entertainment Weekly once called "lunkheaded kegger rock."

Upon arriving at Smoothie King Arena, I noticed two things:

This Stadium Deserves a Better Name: The Romans had "The Coliseum," and the people of New Orleans have a state-of-the-art entertainment complex named after a middling smoothie chain.

This Concert is Sold Out: An artist The Washington Post recently dubbed "The World's Most Hated Band" filled all 18,000 seats of this smoothie-centric stadium.

An obvious paradox arises: how can a band derided as "lunkheaded kegger rock" and widely labeled the worst, most hated group on planet Earth also be so popular? What accounts for the disconnect between Creed's commercial success and dismal reputation?

So today, we'll explore Creed's peculiar cultural standing, unpack the grievances leveled against this band, and examine how Creed hatred evolved into a widespread cultural meme.

Why Do People Hate Creed So Much?

People like when statistics are used as a weapon. When I tell friends and family that I am to attend a Creed concert, I am met with a unanimous response: "You have to write about this!" The expectation is that I will make a meaningful contribution to Creed-bashing discourse through data analysis.

There is a well-worn corner of the internet where music journalists attend Creed shows (ironically, of course!) to document how terrible it was, how foolish the fans are, and how enlightened they must be for recognizing the band's blatant mediocrity.

I refuse, however, to write another "Creed is terrible because they're terrible" article.

It's lazy to hate on something once its hateable reputation is common knowledge.

I had a decent time.

That said, watching this band entertain the Smoothie King faithful made clear why they've earned their reputation as the most hated band on Earth (and, by extension, the galaxy).

One of the most common questions I receive in the run-up to this concert concerns the purpose of our pilgrimage, specifically why this bachelor party is centered on Christian rock. People frequently ask whether my friend "is into Christian rock or something." Here is one of the stranger aspects of Creed's cultural legacy: they are not a Christian rock band while also not-not being a Christian rock band.

This dichotomy appears repeatedly throughout the concert: Stapp openly talks about faith in between songs (like how he applauds 3 Doors Down singer Brad Arnold for "being a man of God" and wishes him well in his battle against cancer) before launching into a tune that is vaguely but not overtly spiritual.

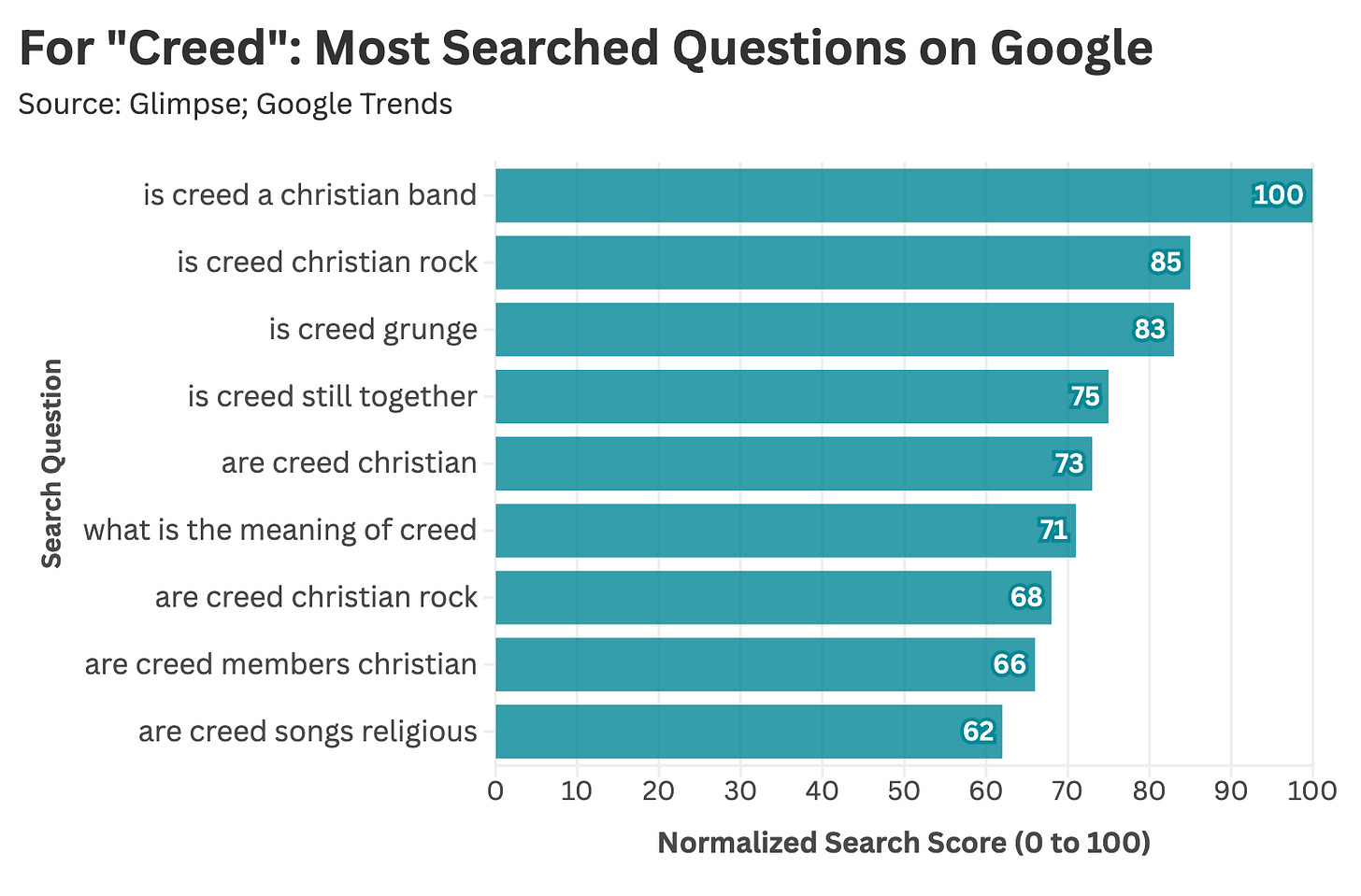

The band's religious artistry is so ambiguous that it's actually the most frequently Googled question about Creed.

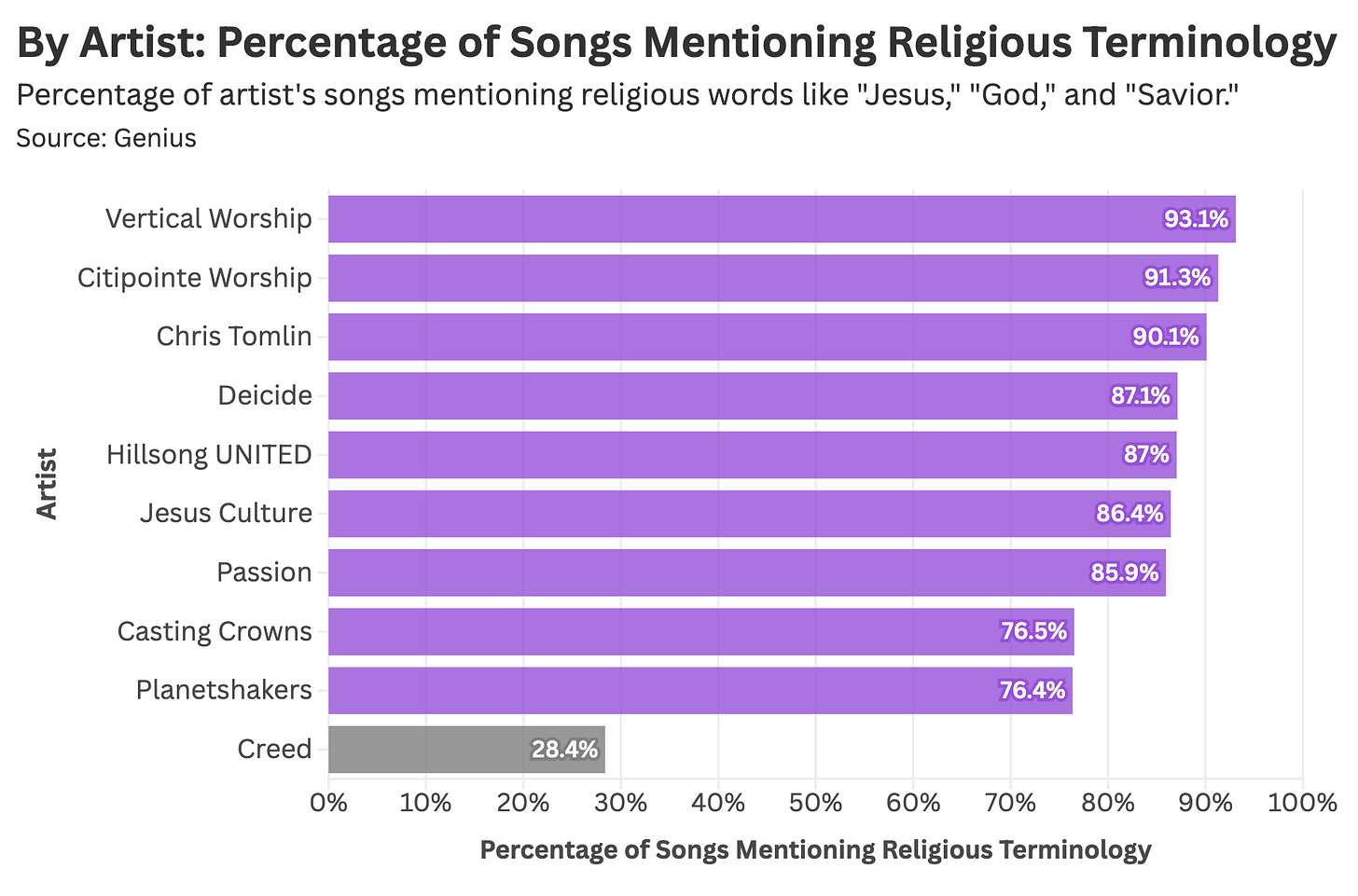

This amorphous religiosity is reflected in the band's lyrics. I searched Creed's discography for lyrical references to faith, focusing on terms like "Jesus," "God," and "Pray," and found the band's usage of these words is only slightly above average. Creed's lyrics are no more religious than those of secular artists like Bruce Springsteen, Nine Inch Nails, and Mumford & Sons, who also mention "God" and "Savior," and the band’s lyrics are significantly less religious than those of Vertical Worship and Chris Tomlin, who explicitly identify as Christian musicians.

There is nothing inherently wrong with Christian rock, and there is nothing wrong with secular music—it's the middle ground between these two, however, that seems to piss people off.

A song like "Higher" received frequent radio play in the 2000s precisely because it does not mention "God" or "Jesus." Yet this song is unmistakably about a higher power and spiritual transcendence.

Creed's furtive religiosity is one of the most common attacks leveled against the band. The rationale behind this critique assumes that Christian rock should exist within its own silo and somehow Creed has violated a separation of Church and Radio.

If I'm being perfectly honest, I did fall asleep about twenty minutes into Creed's set. This is mostly because I drank alcohol and had been in the hot New Orleans sun all day, and only partially because the band had yet to play a song I knew.

Three minutes into my slumber, the woman behind me accidentally smacks me in the back of the head. She apologizes profusely for "punching [me] in the head" and explains that she really loves this band and saw them a few days ago in South Carolina. I ask when the band will play "the hits," and she tells me they save these songs for the end.

Creed's setlist is front-loaded with tracks that sound pretty similar (to my virgin ears). Apart from the four tracks I recognize going into the concert, I struggle to tell where one song ends and another begins.

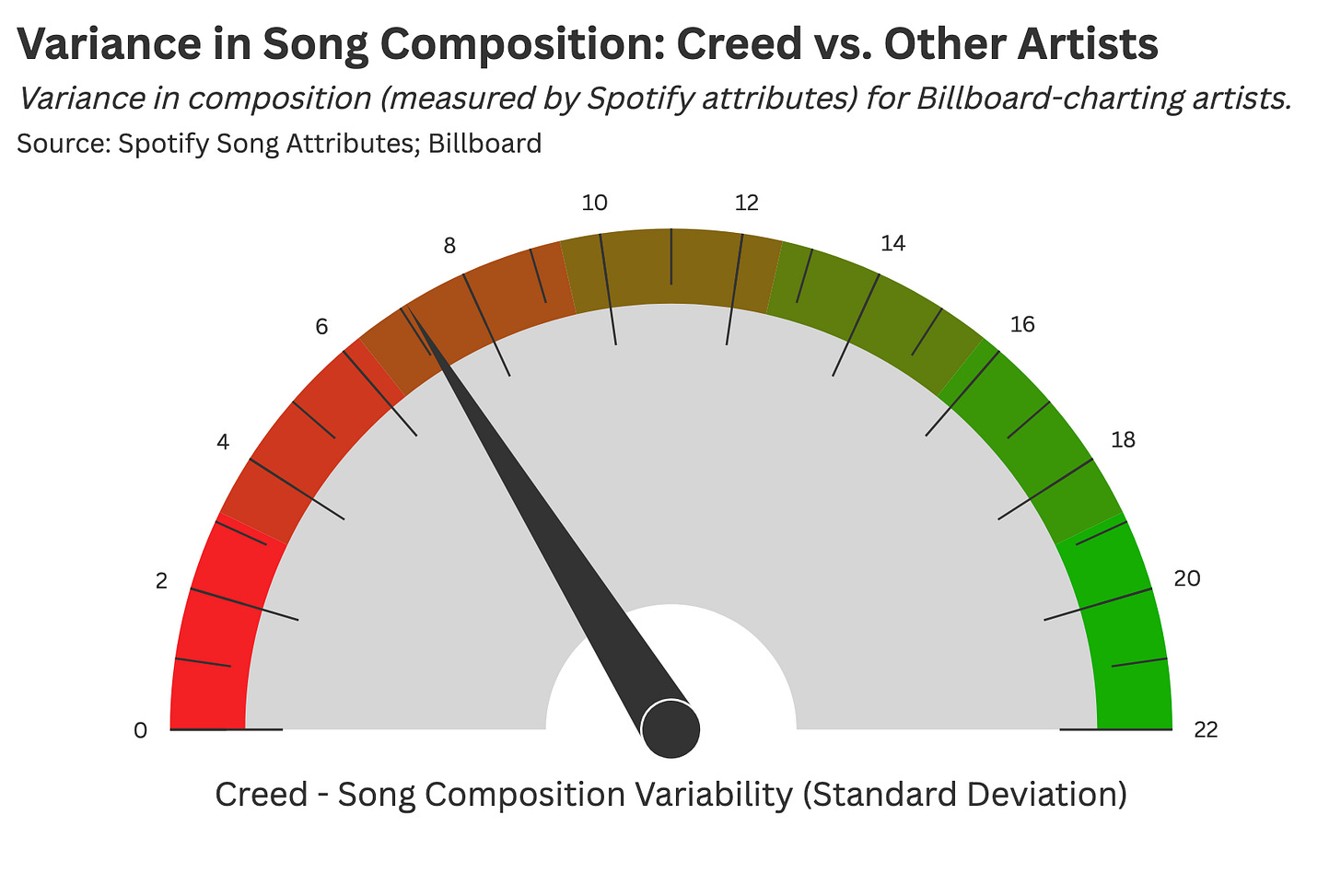

Spotify song composition data confirms my me-search, as Creed demonstrates below-average sonic variety compared to other Billboard-charting artists (though not to the point of self-parody, like Fall Out Boy or Nickelback).

There is nothing wrong with an artist's songs sounding similar. Most people become fans of a band because that act offers a cohesive sound across their body of work—and these same fans will complain if that band strays from the style that made them popular. Lack of variability only becomes a slur when someone dislikes an artist.

Bands like Creed and Nickelback rose to prominence in a pre-streaming era. If you listened to rock radio in the early 2000s, you were bound to hear songs like “One Last Breath,” “How You Remind Me,” and “Photograph.” If you thought these bands were repetitive, then excessive radio play would be all the more infuriating. Today, however, listeners can readily avoid these artists, hermetically sealed in a handcrafted streaming silo.

There's an odd resentment toward Creed for having the audacity to be played on the radio in the early 2000s, despite the band having no agency in this matter. There's a subtle insidiousness to this critique, mainly that it highlights a cultural divide underlying Creed's dueling reputations.

I typically avoid politics, religion, and using states and cities as cultural proxies, but there is no way to write about this band without touching on all three. Typically, cultural punching bags emerge from a disconnect between an artist's popularity (tangibly defined by commercial success) and their reputation as shaped by the media.

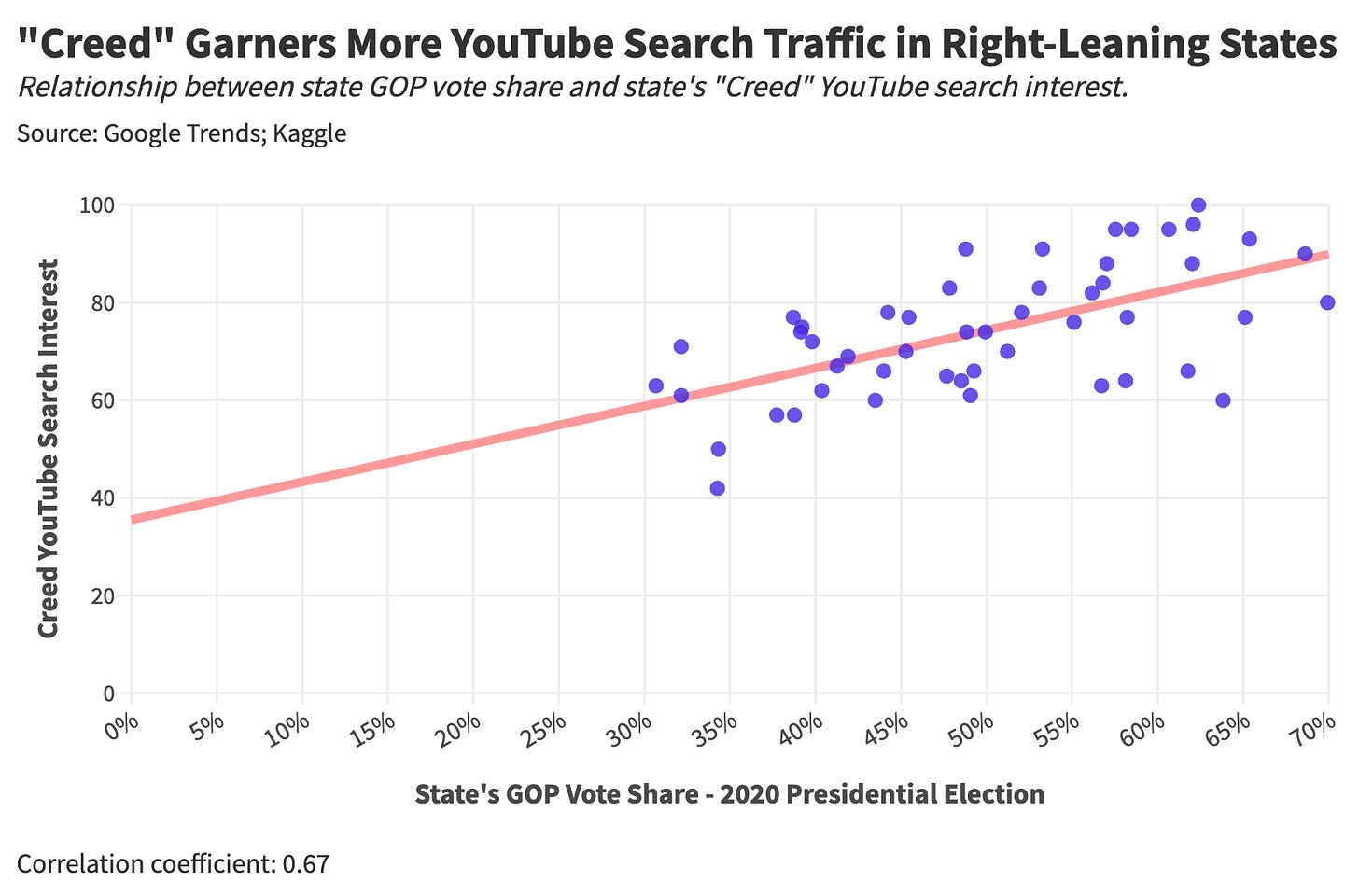

In many cases, a band or TV show is disdained by left-leaning journalists and enjoyed by those who couldn’t care less about the opinions of these journalists. Indeed, when we examine state-level YouTube search traffic for Creed, we find a strong correlation with Republican votership in the 2020 presidential election.

Creed frequently serves as a cultural avatar, shorthand for art favored by those from a different background. Washington Post writers are barred from meaningful critiques of the president, but Big Daddy Bezos has no problem with his journalists calling Creed "The World's Most Hated Band." Does this mean Creed is the victim of some leftist plot to shadow-ban their music? No. More likely, writers feel comfortable dunking on this band because they're culturally detached from Creed's fanbase.

Over time, this deluge of bad press amounts to algorithmic fact. If you Google "Worst Band," Creed appears as the top result, an outcome driven by Google indexing hundreds of articles referring to Creed as "the worst band."

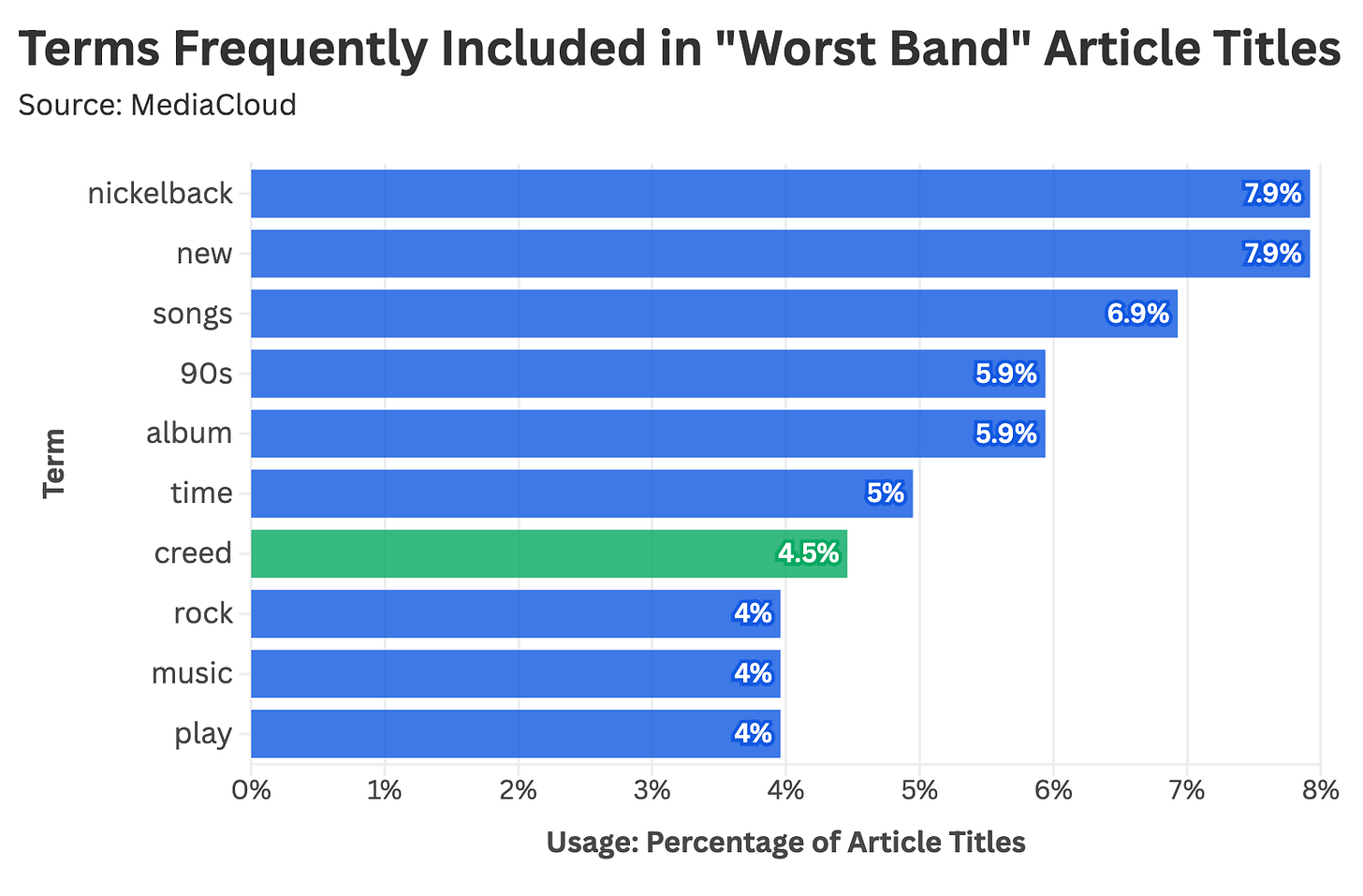

Using a tool called MediaCloud, we see that "Nickelback" and "Creed" are among the ten most common terms used in "worst band" article titles, ahead of words like "music."

According to MediaCloud data, Rolling Stone, Spin Magazine, Vice, NPR, and The New York Times contribute most frequently to these indexed search results.

Unfavorable media coverage precipitates a self-reinforcing cycle of negative press. A band becomes famous, then becomes widely-known for being famously "bad," and is subsequently immortalized (by way of meme-ery) for being a widely-known thing that "everyone" agrees is bad.

I, however, disagree with this characterization, as do 18,000 New Orleanians (which, according to Google, is what you call someone who lives in New Orleans). Sure, I fell asleep for a few minutes and got duffed in the head for my inattention, but I also had a decent time at the Creed concert.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: I Was Taken Higher

As the concert drew to a close, I was disappointed. There were four songs left, and I had yet to hear anything memorable. Fortunately, Creed saved their biggest hits for the end. In the span of twenty minutes, the band blew the roof off of Smoothie King with four indisputable bangers.

The obvious high point of this stretch was when Scott Stapp asked the audience, "Do you want to get Higher?" which had the opposite effect of a sex safe word—everyone in the arena lost their minds. As Stapp crooned the chorus to "Higher," everyone wrapped their arms around one another and sang along. I saw my friends embrace total strangers with no sense of irony. The woman behind me offered a thumbs up, confirming that they were now playing the hits, and once again apologized "for punching [me] in the head."

At this moment of peak social cohesion, I was overcome by déjà vu: this was the first song I ever downloaded on iTunes. I was nine years old and knew nothing of this band's reputation; I simply thought "Higher" was a fun song about someone's desire for verticality. If you told me this song was vaguely religious, I'm not even sure what I would have done with that information.

The grievances underlying Creed's poor reputation are learned through cultural osmosis. A nine-year-old is not preoccupied with status, religion, culture wars, or parroting the opinions of a decade-old Rolling Stone poll; a nine-year-old downloads a song he or she likes while thinking no better or worse of themselves. Only after years of being told that this band is terrible—and accepting the idea that those who enjoy their music are somehow different, and that this difference is negative—does the band's memetic legacy solidify. Eventually, the rationale behind Creed-bashing becomes circular: they're bad simply because everyone says they're bad, and that's that.

As we exit Smoothie King Arena, I have to admit that I had a good time. I buy my friend a "Greatest Halftime Show Ever" t-shirt, so he can proudly display angel Scott Stapp across his chest whenever he wants.

To some, Creed symbolizes mildly repetitive music enjoyed by those who are different; a band so famously "bad" that this judgment is seemingly self-evident. To me, however, Creed is a band that put on a decent show. As such, I will not be suing them anytime soon.

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

An interesting comparison based on the Christian/Non-Christian dichotomy is U2. They sing about God often but aren’t billed as Christian rock. People also have polarizing reactions to them too

Thoroughly enjoyed that article (as I do all the Stat Significant articles), and particularly like the final sentiment! Not a Creed fan (I don't even like "the hits") but that really doesn't matter - as you say, many people have a great time at their concerts, and that's all that matters. It's kind of comforting to know in today's increasingly separated world, thousands of people go to share a communal experience of enjoying the band they love.