Which Decade(s) Saw the Greatest Change in Popular Music? A Statistical Analysis

Which decades saw the greatest shifts in mainstream music?

Intro: What is New Music Missing?

In a recent Q&A with the music newsletter New Bands For Old Heads, I was asked a rather mundane question that partially shattered my sense of self:

"Has any new music caught your attention recently (in a good way)? Or is it mostly off-putting? Why? What is new music missing for you?"

I've been in a music rut for the past five years, so my initial reaction was one of overwhelming crankiness (spiritually, using caps-lock):

I DON'T "GET" NEW MUSIC—IT'S ALL AI SLOP!

¡I DON'T UNDERSTAND CHAPPELL ROAN'S COSTUMES!

MUSIC WAS BETTER IN THE 1990s AND 2000s (despite Nickelback and Creed making the Billboard charts a combined 36 times)!!!

Thankfully, I caught myself before responding like an Amazon product reviewer or Nextdoor busybody. Still, my impulse toward cultural NIMBYism led me to reflect on how popular music has evolved in tandem with my personal development.

Just a few years ago, I embraced new works; now, my attitude toward Top 40 could best be described as "remarkably grouchy." Part of this shift can be attributed to cognitive development, as human "open-eardness" naturally wanes with age. Yet an equally significant factor lies in the ever-changing nature of music itself. Year after year, music mutates, with newfangled stylistic variations supplanting yesterday's novelties.

So today, we'll explore the decades that saw the greatest shifts in music design, examine how quickly the zeitgeist changes, and identify the genres that spurred these paradigmatic evolutions.

Which Decade(s) Saw the Greatest Change in Popular Music?

Our analysis will track changes in song composition for mainstream music over the last seven decades. We'll define popular tracks as works listed on The Billboard Hot 100 and utilize Spotify's database of song attributes to identify shifts in music design.

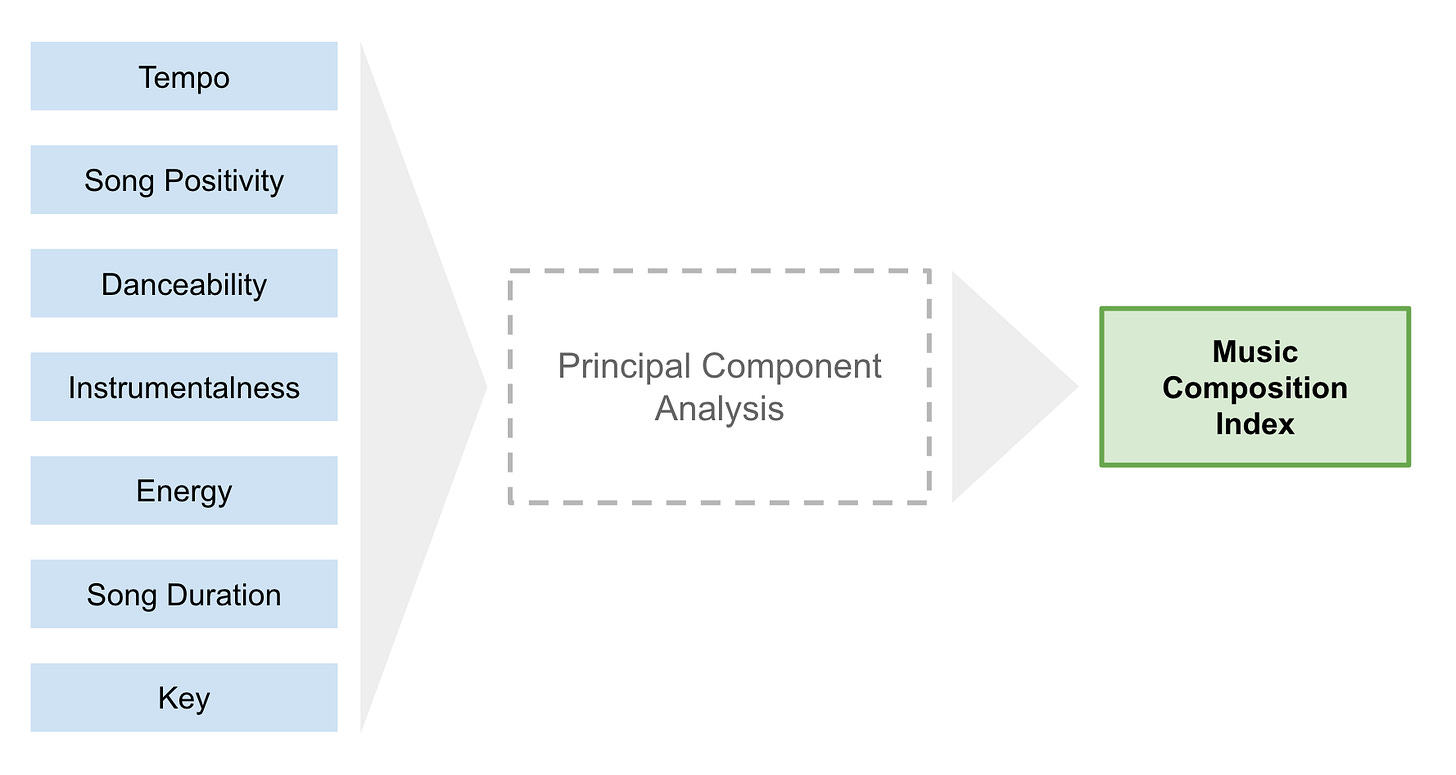

We'll use a statistical technique known as principal component analysis to condense twelve Spotify song variables—such as tempo, danceability, song duration, positivity, and instrumentalness—into a single figure, which we'll call our “Music Composition Index.” For each Billboard-charting track, we’ll produce an index score that ranges from 0 to 100.

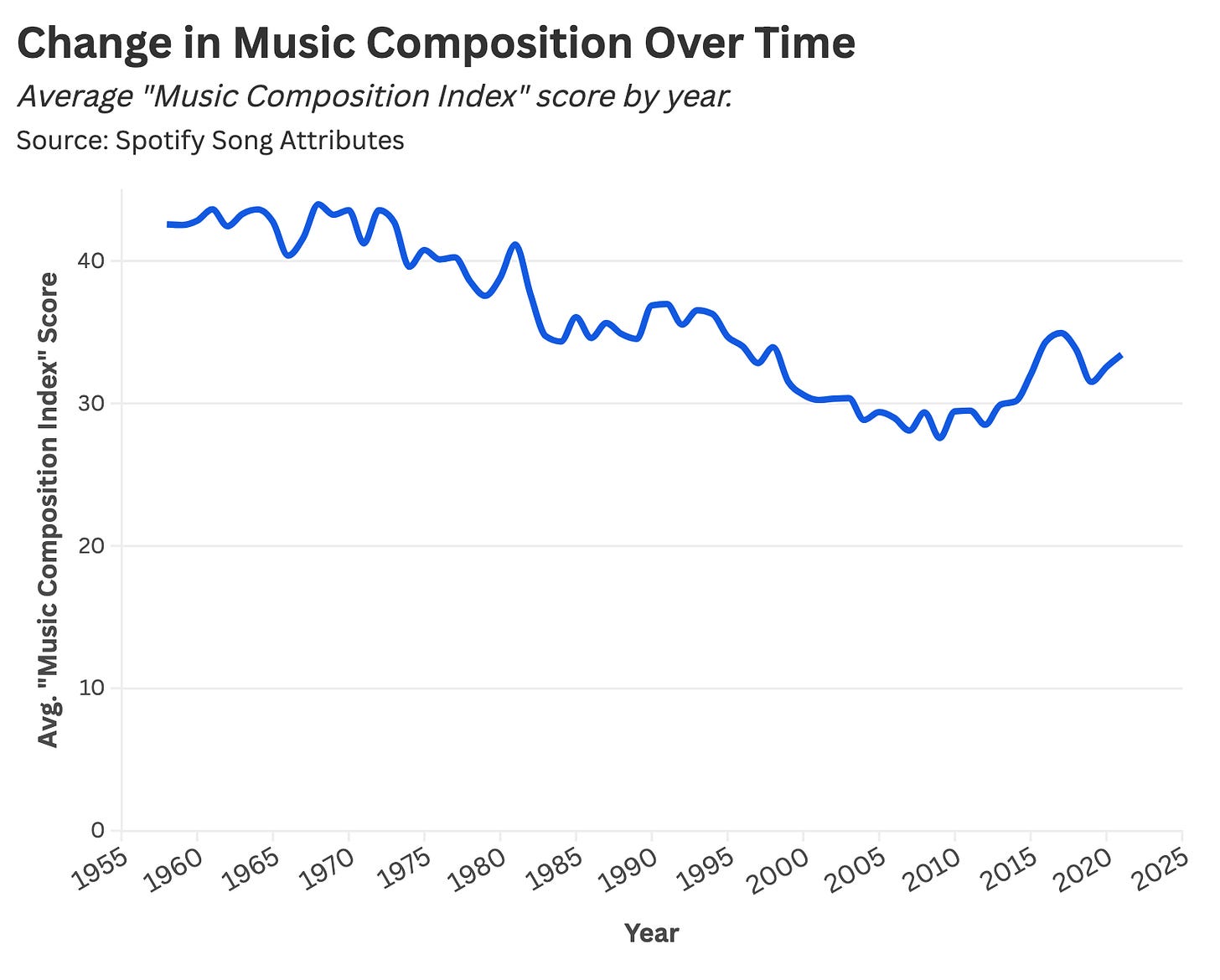

We'll then calculate the average Music Composition Index for a given year or decade, using these figures to identify shifts in sonic design. Think of these averages like the S&P 500: the index number itself isn't inherently meaningful, but its movement relative to previous periods reveals significant changes in music style.

When we chart annual averages for our Composition Index, we observe the subtle evolution of Billboard-charting works, marked by periods of pronounced transformation in the early 1980s and 2000s.

To better illustrate Top 40's continuous evolution, we can calculate how our index metric changes, in percentage terms, from one year to the next.

According to this relative change statistic, music composition shifts by a modest 0.4% yearly, interspersed with periods of notable evolution.

At first glance, a 0.4% change may seem negligible. However, compounded over a decade, these subtle shifts and pronounced swings can result in a 5% to 15% difference in song composition—significantly reshaping musical positivity, energy, lyrical complexity, runtime, and other Top 40 conventions. Consider the 1950s, for example, which began with polished, chart-topping pop standards by Nat King Cole and Tony Bennett and ended with frenzied rock & roll hits from artists like Bill Haley and Elvis Presley—a seismic realignment in just ten years (that's two Olympics-worth of time!). So, if you've encountered new (or old) music and thought, "WHAT IS THIS?" know that's just sonic Darwinism at work.

Our relationship with music is further complicated by periods of rapid stylistic upheaval—most notably during the 1980s and 2000s—when mainstream tastes underwent a dramatic transformation. Each of these eras marked the emergence of new subgenres and influential pop icons: the 1980s gave rise to artists like Madonna, Hall & Oates, and Journey, while the 2000s spotlighted Rascal Flatts, Usher, Eminem, Taylor Swift, Toby Keith, and Beyoncé.

By examining the artists who defined these decades, we can begin to unravel the industry dynamics that reshaped the Billboard charts. Ultimately, rapid evolutions in song composition were driven by a select group of fast-emerging genres, accompanied by the simultaneous decline of well-worn styles. This proverbial changing of the guard permanently redefined Billboard's Top 100 for decades to come.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

The Rise and Fall of Once-Beloved Genres

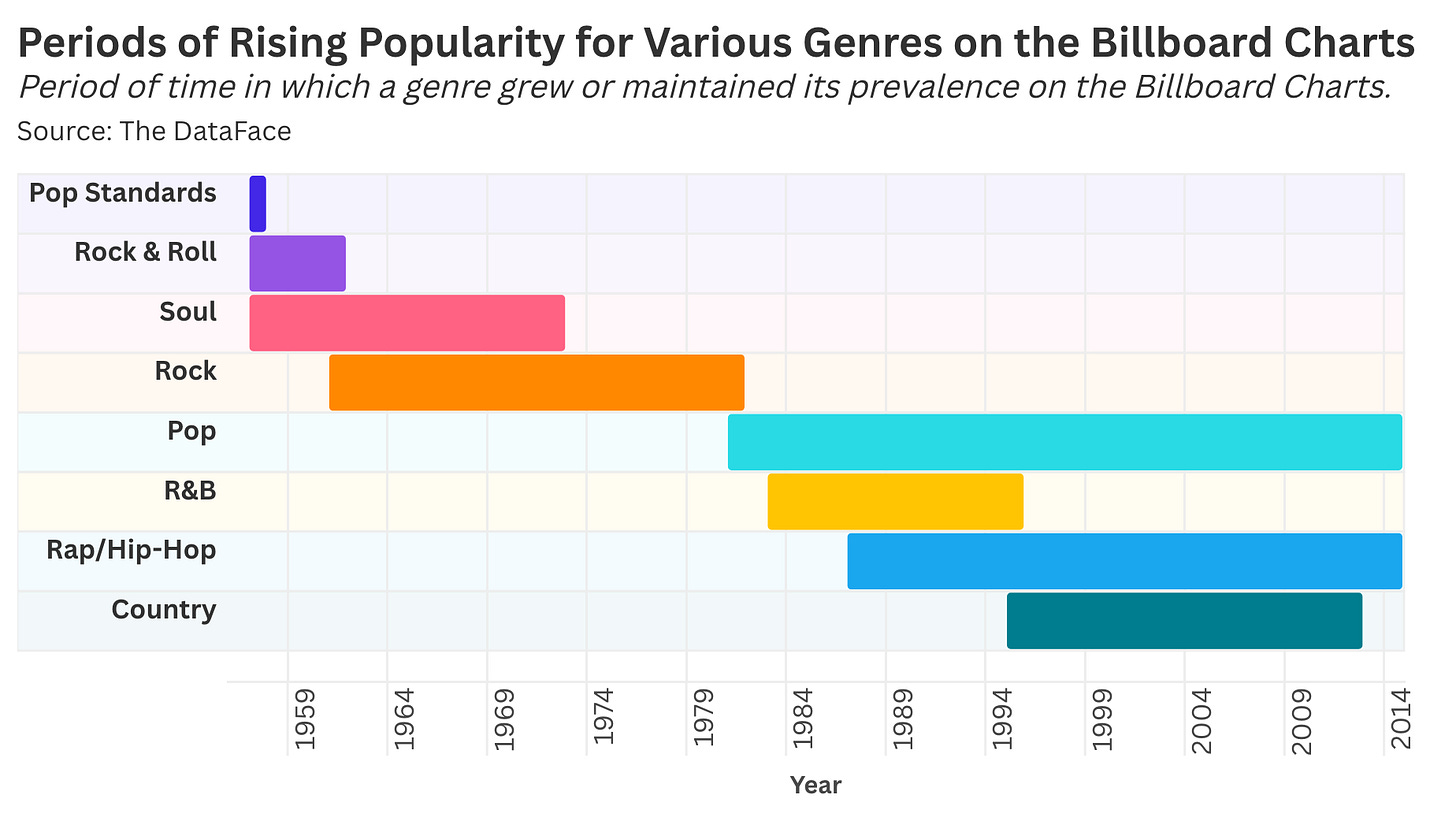

Genre popularity is cyclical, with new styles continually emerging and receding from the mainstream. When we track the prevalence of various formats in the Billboard Top 100, we observe a handful of metaphorical "baton passes" from one fashionable format to the next: the nebulously named "pop standard" is replaced by rock and soul, which are later replaced by a combination of pop, rap, hip-hop, and country.

In short, the music landscape of the late twentieth century is defined by the monocultural dominance and dramatic collapse of rock. In the 1980s, rock accounted for nearly 60% of songs in the Billboard Top 100; by the 2000s, this figure had fallen to 8%.

Rock's precipitous decline can be attributed to numerous factors, chief among them the genre's creative stagnation during the late 1970s and early 1980s. This era was marked by commercial overexposure and widespread imitation, exemplified by glam bands such as Poison, Mötley Crüe, and Bon Jovi—whose flashy yet formulaic style came to symbolize the format's demise.

This period of cultural inertia opened the door for other musical formats. When we chart each genre's rise (the period when its share of the Top 100 was growing), we see the 1980s mark the end of rock's cultural dominance and the start of unprecedented growth for several genres—such as pop, hip-hop, and country—that now shape our contemporary landscape.

The stylistic realignment of Top 40 during the 1980s can be traced to two rapidly adopted innovations:

The Rise of Synths and Drum Machines: The introduction of synthesizers and drum machines shifted pop music toward electronic instrumentals, giving rise to ascendant (sub)genres like new wave, synth-pop, and hip-hop. Artists like Madonna, Michael Jackson, Duran Duran, New Order, Prince, and Eurythmics capitalized on these new technologies to merge traditional pop and rock with electronically produced instrumentation.

Rap, Hip-Hop, and the Preeminence of Lyrics: Hip-hop and rap originated in the Bronx during the 1970s, evolving from DJs delivering spoken rhymes over looped breakbeats. The genre quickly gained recognition for its rhythmic intensity and lyrical sophistication.

The swift adoption of these music stylings marked the end of rock's dominance, first capturing popular imagination in the 1980s and then fueling the genre's obsolescence in the 2000s.

Being a music listener during this twenty-year span meant experiencing a radical transformation in popular music. Someone coming of age in 1977 encountered a wildly different sonic landscape than teens in 1985, 1991, or 2003. Here, we see the maddening interplay between musical identity and ceaseless cultural evolution: listeners often gravitate toward the hits of their youth, embracing music from a five- to ten-year window. If your teenage years fell in the 1970s, you're probably drawn to classic rock; if you belong to Gen X, your musical preferences likely lean toward a blend of grunge and pop.

Twenty years from now, Gen Alpha will lament how Gen Beta(?) embraces an entirely foreign subgenre that formed as a newfangled fusion of pop, rap, and country—and so the cycle of never-ending Top 40 evolution continues. No one is immune from sonic Darwinism.

Final Thoughts: From Chuck Berry to Nickelback

Music history is defined by a series of epochal shifts, where clusters of stylistic innovation give rise to new genres and movements. Just as genetic mutations become dominant in a gene pool, musical innovations can spread and evolve, reshaping mainstream culture.

Our made-up-yet-totally-awesome Music Composition Index further illustrates this iterative development process, underscoring how music design follows a distinctly linear path. Rather than chaotically leaping between disparate genres, Top 40 is forever evolving, with artists blending new elements and established styles.

The downside of this persistent sonic advancement is that pop culture is forever unmoored: what was once Chuck Berry gave way to The Beatles and Led Zeppelin, which birthed Journey and Mötley Crüe, which precipitated a countercultural response from Nirvana and Pearl Jam, which birthed watered down imitation in the form of Nickelback and Creed. If you got reverse-Back-to-the-Future-d from the 1950s to the 2000s, you'd be greatly disappointed that Chuck Berry's pioneering "Johnny B. Goode" somehow spawned Nickelback and Creed (within a few degrees of separation).

Sure, it's lamentable that music's relentless evolution places Imagine Dragons and Hanson in the same lineage as The Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin. Yet consider the counterfactual—an alternate universe where music never changes, new styles never emerge, and everything remains predictably the same. In this static, pleasantly Orwellian culture, no one would feel left behind. Thirteen-year-olds would share the music tastes of their parents, who would mimic the affinities of their parents—and not a single person would find themselves bewildered by incomprehensible Top 40.

The unintended consequence of this overwhelmingly egalitarian world is that being a teenager would stink. The thrill of adolescent identity formation would be non-existent if everyone liked the same things and culture stood perfectly still. Your bedroom walls would be lined with hand-me-down posters from your parents—who inherited these same posters from your grandparents.

Nobody likes feeling out of touch, nor do we relish seeing rock's subversive vitality morph into acts like Creed and Imagine Dragons—but that's the price we pay for music's constant evolution and its outsized significance during our formative years.

You might not understand Chappell Roan's music or outfits, but you can take comfort in knowing this: someone, somewhere, feels a little more special because they "get" Chappell Roan, and you don't.

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Fascinating. One obvious point: The platforms for finding new music have changed even more dramatically than the music itself. Elvis and the Beatles found their audiences through network television and AM radio stations. 📻 All that seems quaint as vaudeville today.

as somebody who pretty much doesn't listen to any top 40, and rarely knows what's in it (save for a handful of accidental crossovers into my universe), it's always fascinating to see these kinds of analyses because rock is still so prevalent in my own listening patterns and recommendations. i have no beef with top 40; it's just funny to get these reminders about how far removed i am from the real world sometimes.