When Do TV Shows "Jump the Shark"? A Statistical Analysis.

What season does a TV series become unwatchable?

Intro: Bad Television and “Jumping the Shark”.

Happy Days was among the most popular shows of the late 70s and early 80s. The series offered a nostalgic portrait of America's golden years (post-war 1950s) and introduced audiences to "The Fonz," an iconic character described as "the essence of cool." The series was a massive success as its fourth, fifth, and sixth seasons finished top-5 in annual viewership. And then the show went downhill. Year after year, Happy Days' ratings declined until its eleventh and final season placed 63rd, with viewership numbers nearly 1/3 of its peak seasons. So what happened?

Jon Hein, an American radio personality and early internet webmaster, studied Happy Days' decline to locate the show's quality inflection point. Hein and his roommate zeroed in on season 5, episode 3, as the onset of Happy Day's demise. In this particular episode, the characters visit Los Angeles, where a water-skiing Fonzie answers a challenge to (literally) jump over a shark. The stunt was seen as an attempt to generate elevated attention in a way completely unrelated to the series' central storyline.

Hein later created the now-defunct JumpTheShark.com, curating an ongoing list of fallen television shows and his arguments for the moments each series "jumped the shark." Over the years, the idiom "jumped the shark" has grown in prevalence and broadly signifies the point a popular or critically acclaimed television show begins its inevitable decline in quality.

There's great excitement in discovering a new television show. Week after week, we can enjoy the familiar comforts of characters, story, and setting that are reliably entertaining — until it all goes south. Whether it's Game of Thrones' inglorious final season, House of Cards when they crudely jettisoned Kevin Spacey's character (for good reason), or How I Met Your Mother's extremely unsatisfying finale — we've all felt the pain of a once-loved show betraying itself. Sometimes shows lose their mojo because of casting changes or radical shifts in narrative; other times series simply go stale.

There is an expectation that most long-running shows will degrade in quality over time. With each returning season, the likelihood of jumping the shark grows. So is there a predictable point when shows begin their inevitable decline? Should all series quit after a pre-specified number of episodes? Can there be too much of a good thing when it comes to television?

Methodology: When Do Shows Typically Jump the Shark?

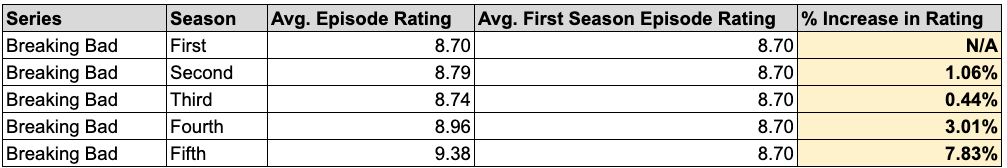

Our goal is to identify patterns in industry-wide series quality by tracking rating fluctuations over time. We'll utilize IMDB user reviews as our marker for episode caliber and map acclaim by comparing a series' first season average to subsequent season scores. As an example, here is what our methodology produces for Breaking Bad:

Breaking Bad's ratings slowly improve relative to their first season baseline, with the fifth season yielding a noticeable jump in viewer appraisal. We can thus infer that Breaking Bad does not jump the shark.

Or take the American version of The Office:

The Office's ratings exceed its first-season scores until Steve Carrell leaves the show at the end of season seven. The resulting drop-off is a clear-cut inflection point for series quality (as judged by fans).

We will perform this same analysis for individual series and then examine global quality trends by season number.

Dataset:

The Internet Movie Database (IMDB) is the de facto online hub for film and television, providing visitors with a comprehensive encyclopedia of entertainment knowledge. IMDB also boasts a massive library of user-generated content, as consumers evaluate various media through free-form text reviews and star ratings.

IMDB operates with tremendous scale as the 63rd most visited site on the internet, averaging nearly 500M in monthly internet traffic. To provide an example of content depth, Better Call Saul (the 34th-ranked TV series on the site) holds 531,000 user ratings — nearly the population of Wyoming.

IMDB's television library is (quite honestly) too exhaustive, with details for nearly every known television production worldwide since TV’s inception. Therefore, to narrow scope and ensure familiarity with noteworthy data points, we'll focus on US-based television shows that ran three seasons or longer and sit in the top 5% of IMDB rating counts, a total of 550 TV shows.

Analysis Overview:

Our analysis will address the following questions:

On average, which season do long-running TV shows begin to perform worse than their first season?

What shows featured the heaviest degradation in season ratings relative to their first season?

Which series showcased the most significant ratings improvement compared to their first season?

Have there been changes in the quality and frequency of long-running TV shows?

When do TV Shows Begin to Perform Worse than their First Season?

Simply getting a show on the air is a herculean accomplishment. Based on reports from the Writers Guild of America (WGA), roughly 50,000 film and television screenplays are written annually (which doesn't include scripts written by non-WGA members). A meaningful percentage of the aforementioned 50,000+ scripts are developed for television, and around 500 of these shows are eventually produced. Pretty crazy, right? Well, the struggle continues. On average, 30 to 50% of premiere series are renewed for a second season. And what if you aspire for a fifth, sixth, or seventh season? Well, those odds are equally ludicrous.

At a certain point, a series loses the creative and commercial momentum that propelled it through entertainment's daunting production funnel. And it appears this momentum typically slows around season six:

When averaged, show acclaim follows a discernible arc, with ratings peaking in season two and declining with every subsequent season. Perhaps TV series should be capped at five seasons.

What Shows Declined the Most?

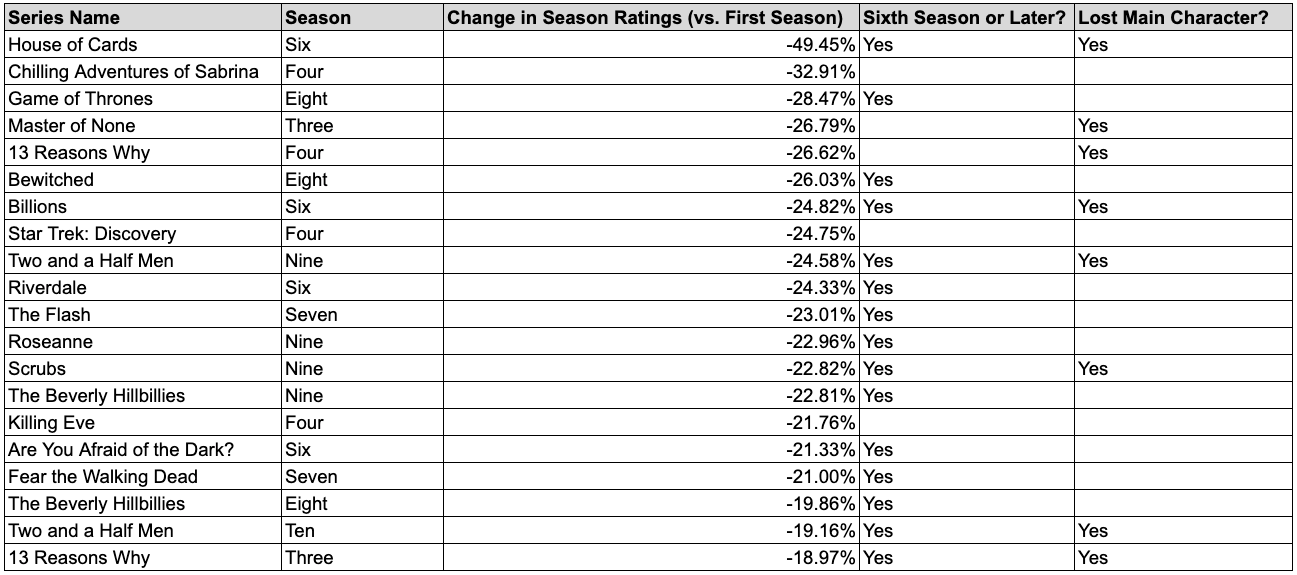

Anyone who watched House of Cards will know that Kevin Spacey's Frank Underwood dominated much of the show's screen time, often serving as series narrator in addition to its leading figure. Given the immediacy and extent of Kevin Spacey's cancellation, the show could not facilitate a suitable narrative for his departure. Instead, Spacey's absence was relegated to a clunky throwaway line about Underwood's assassination. As a result, viewers slogged through an entire season of House of Cards without the person most responsible for the house of cards. Watching season six of Netflix's hyper-cynical depiction of Washingtonian politics was painful — and it appears IMDB users agree.

We can spot two overwhelming trends in our list of markedly inferior seasons. First, 75% of poor performers occur season six or later. Second, many subpar seasons follow the departure of a series lead. Who wants to watch Two and a Half Men without Charlie Sheen, Scrubs without Zach Braff, House of Cards without Spacey, or 13 Reasons Why absent the character who made the list of 13 reasons? The answer is fewer people.

What Shows Improved the Most?

Some shows take a while to find their footing. Our list of series with quality improvements throughout their run features comedy and sci-fi shows with faulty first seasons. Parks and Rec, which headlines this list, was nearly canceled following its initial season and underwent a substantial overhaul in tone and character development between seasons one and two. Likewise, Seinfield, often considered the greatest sitcom of all time, struggled to find an audience in its first three seasons. Seinfeld's fourth season saw a jump in viewership following an Emmy nomination for Best Comedy, a handful of now-classic episodes (The Contest, among them), and a new time slot behind Cheers.

Maybe comedy and fantasy series take a while to establish themselves and find audiences. Or maybe viewers possess greater loyalty to a high-quality show from these genres. Or maybe both.

Sixth Season Quality and Frequency over Time.

So how has quality changed in a world of ever-proliferating television? Are more TV series jumping the shark? Looking at shows in the top 10% of IMDB rating counts (1450 series), we can track the quantity and acclaim of sixth seasons over time:

Since the early 2000s, there has been a surge in series running at least six seasons, which makes sense because there is more TV. From the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, sixth-season ratings improved, followed by a trend break around 2017. So what happened? My best guess: the streaming wars went into overdrive.

The list of channels producing original content grows by the day: NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, TBS, FX, The CW, Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, HBOMax, Prime Video, Peacock, Paramount Plus, Apple+, Cinemax, EPIX, Showtime, Starz, The Roku Channel, and Vudu, to name a few. Over the past few years, many of these platforms expanded content creation efforts, leaving us with an ever-increasing roster of shows that are diluting overall content quality. Unfortunately, the entertainment industry can only produce so much television (and consume so much of our time) before acclaim hits diminishing returns.

Final Thoughts: Is There an "Enough?"

Many years ago, famous authors Joseph Heller (Catch-22) and Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse Five) were at a party given by a billionaire on Shelter Island.

Observing the billionaire's gaudy affluence, Vonnegut remarked, "Joe, how does it make you feel to know that our host only yesterday may have made more money than your novel Catch-22 has earned in its entire history?"

"I've got something he can never have," replied Heller.

"What on earth could that be, Joe?" said Vonnegut.

"The knowledge that I've got enough," said Heller.

Humans struggle with conceptualizing "enough." There was once a time when resources were scarce (long before TV), but now we live in an age of abundance, armed with primordial instincts to covet and accumulate. So we eat as if we’re preparing for a long winter, we fixate on the stock market (and other instances of "number go up"), and we produce television content until that content has thoroughly (and quite painfully) jumped the shark. Growth maximization is our de facto mindset.

It's rare when shows exit on top. Nevertheless, certain series are often labeled as finishing "too soon." Breaking Bad, The Wire, Fleabag, Bojack Horseman, The Office (U.K. version), Atlanta, Watchmen, Broad City, and Schitt's Creek are examples of series given this designation. Many of these productions ended of their volition and on their own terms. But imagine if these shows had run four more seasons. Would Breaking Bad still be a perfectly-packaged masterpiece in its hypothetical ninth season? And would we still cherish Phoebe Waller-Bridge's Fleabag following a steep decline in season seven ratings? Probably not.

So, where does TV quality go from here? There isn't some insidious plot to tarnish television quality; TV executives are rational actors responding to incentives. The streaming wars will be won by the platform that can maximize time consumption in a highly cost-efficient manner. Launching a new television series carries risk. Development and production require intensive capital investment without knowledge of viewer reception. What would you pick if you were a TV exec and had a choice between season nine of Breaking Bad or developing an unknown commodity? Maybe Walter White left the show in season seven, but people still seem to watch, so why not? As the streaming wars continue, increasing dollar share will go toward cost-efficient content production, like reality TV, low-cost documentaries, and long-running narrative series with established bases.

Advances in media distribution have fostered a Cambrian explosion in television content. And, sure, more series will jump the shark, but increasing volume will also spawn a proliferation of high-quality shows — and I guess that's more than "enough."

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

The opposite of "jumping the shark" is called "growing the beard", after the observation that Season 3 of Star Trek: The Next Generation was noticeably better than the first two, and it was also the first season in which Riker had a beard.

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/GrowingTheBeard

13 reasons why shows up twice in the first chart with different values. Odd.