When Did "Rock" Become "Classic Rock"? A Statistical Analysis

When—and why—did "rock" become "classic rock"?

Intro: When Did Mötley Crüe Become Classic Rock?

I first grasped the strangeness of the term “classic rock” while listening to a pop-punk song. In 2004, Bowling for Soup topped the charts with “1985,” a track about a frustrated housewife nostalgically longing for her Reagan-era youth.

During the song’s bridge, our protagonist laments cultural change: “She hates time, make it stop. When did Mötley Crüe become classic rock?” It was at this moment that I—a teenager—first understood the peculiarity of genre:

Apparently, there was a band called Mötley Crüe.

This motley crew was initially classified as one genre—rock—before being reclassified as “classic rock.”

Contrary to my longstanding belief, “classic rock” was not etched into the Ten Commandments—it was a contemporary radio format, likely devised by someone in public relations.

As an adolescent, I never considered that rock had not always been “classic.” Yet the term’s cultural ubiquity raises questions about when—and by what process—this genre rebrand occurred. To answer (and broaden) Bowling for Soup’s throwaway-lyric-turned-age-old question: when did Mötley Crüe (and The Beatles and Bruce Springsteen and The Who and so many other artists) become classic rock?

So today, we’ll trace the rise of the genre known as “classic rock,” examine how the term entered popular culture, and determine which artists headline the classic rock music canon.

When Did “Rock” Become “Classic”?

The tale of classic rock begins where many cultural myths do: with advertising revenue.

In the late 1970s, several rock radio stations realized their core audience was aging out of youth-oriented Top 40 programming. These diehard listeners—largely affluent Baby Boomers entering their peak earning years—were more attractive to advertisers than younger audiences with limited disposable income.

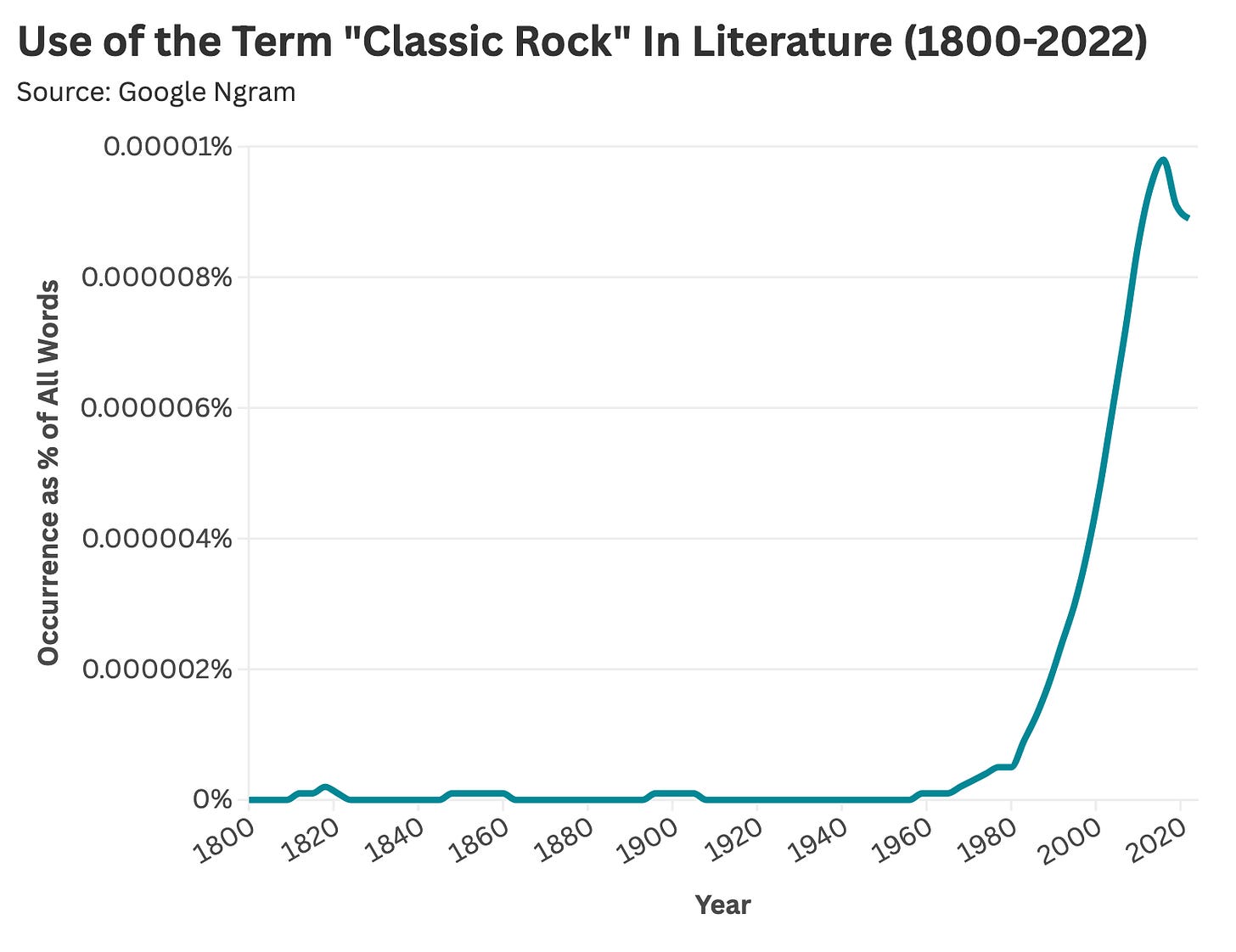

Literary references, as tracked by Google Ngram data, indicate that the term “classic rock” first appeared during this period, then spread rapidly beginning in the early 1980s.

These references emerged in response to changes in radio programming, documenting—and ultimately consecrating—the genre’s rebrand. As a result, use of the term “classic rock” trails a widespread shift toward the format itself. This raises a natural follow-up question: can we pinpoint the precise moment (or moments) when radio programming catalyzed that transition?

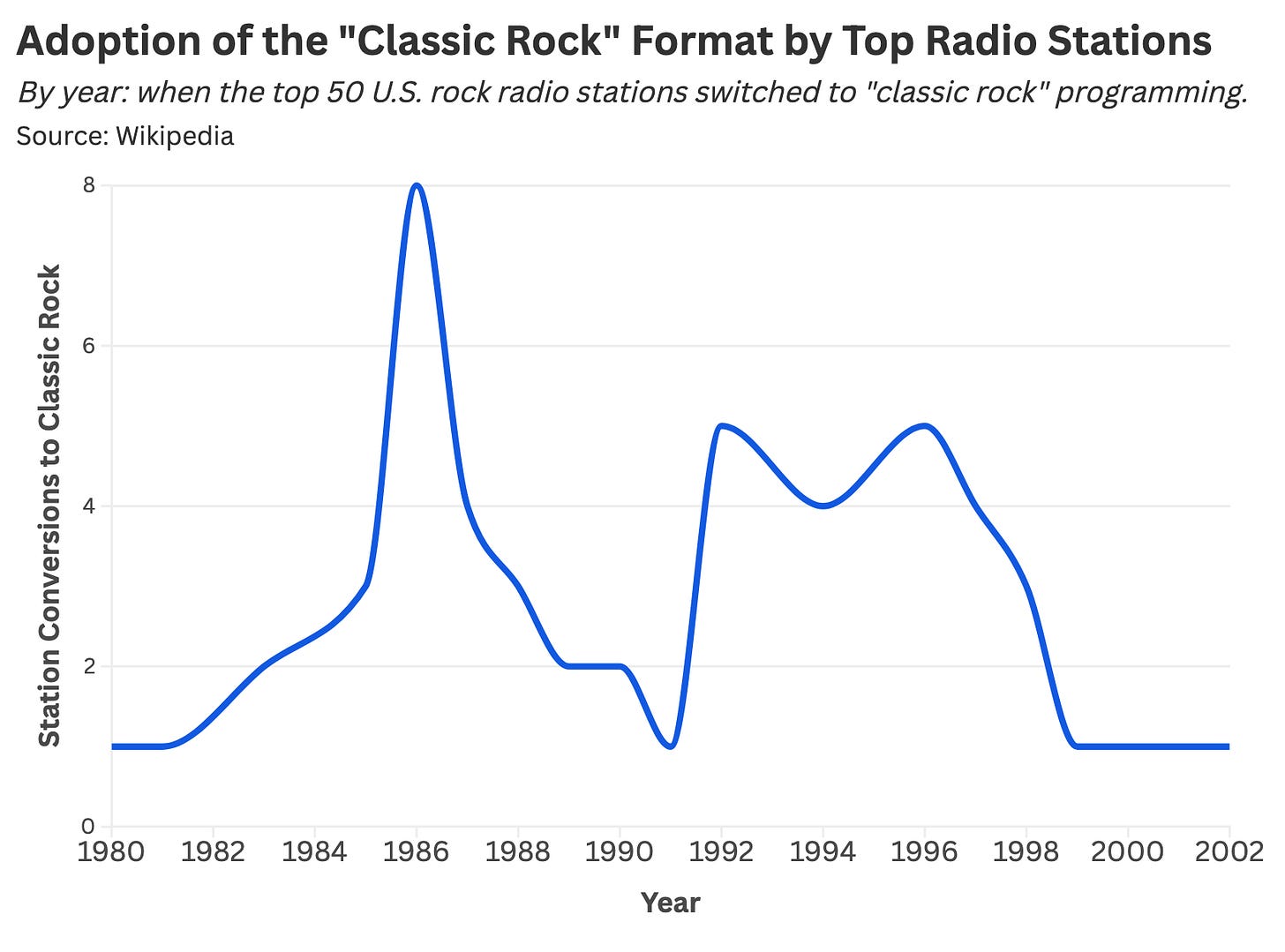

To locate the end of “rock” (sans “classic”), we’ll investigate when radio stations began adopting the classic rock format. In researching this piece, I was struck by the abruptness of these format transitions: a Top 40 station would go dark—sometimes for a single minute, sometimes for several days—and later relaunch as a “classic rock” station with entirely different programming. If someone took a week off from this frequency, they might return to something completely unrecognizable.

For most analyses, I rely on clean, well-structured datasets that are easy to analyze. This was not one of those cases. No, for this data, I had to go to Wikipedia, read through (surprisingly thorough) histories of the 50 largest classic rock stations in the United States, and manually record when these outlets changed their programming.

According to these Wiki histories, there are two concentrated periods when channels rapidly switched to classic rock: the mid-1980s and mid-1990s.

Each of these paradigm shifts was driven by changing industry economics:

The mid-1980s: The rise of classic rock programming reflected radio’s myopic focus on aging Baby Boomers, the growing mainstream dominance of pop and hip-hop, and MTV’s increasing monopoly over youth culture. Early in the decade, rock peaked on the Billboard charts, accounting for 61% of hit songs in 1983; by 1991, that share had fallen to 30%. For many stations, switching to classic rock was a pragmatic adaptation—a simpler alternative to chasing new musical trends.

The mid-1990s: The Clinton years saw mass consolidation across the radio industry, culminating in the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Corporations like Clear Channel Communications (now iHeartRadio) began buying up local stations and subsequently prioritizing low-risk, highly profitable formats. Classic rock delivered a reliable 35–54 demographic with proven advertising potential and lower programming costs. At the same time, nascent rock subgenres (like grunge) fragmented, and younger listeners began drifting away from terrestrial radio.

Rock’s rebrand can be understood as the product of two mutually reinforcing phenomena: commercialization and canonization. The commercialization process is relatively straightforward—radio stations packaged a familiar catalog of songs for a lucrative nostalgia-oriented audience. Canonization, however, is far more slippery. How do you draw the line on what qualifies as “classic”? Is Nirvana classic rock? What about Nickelback? And is this collection of artists constantly changing, or frozen in time as of 1986?

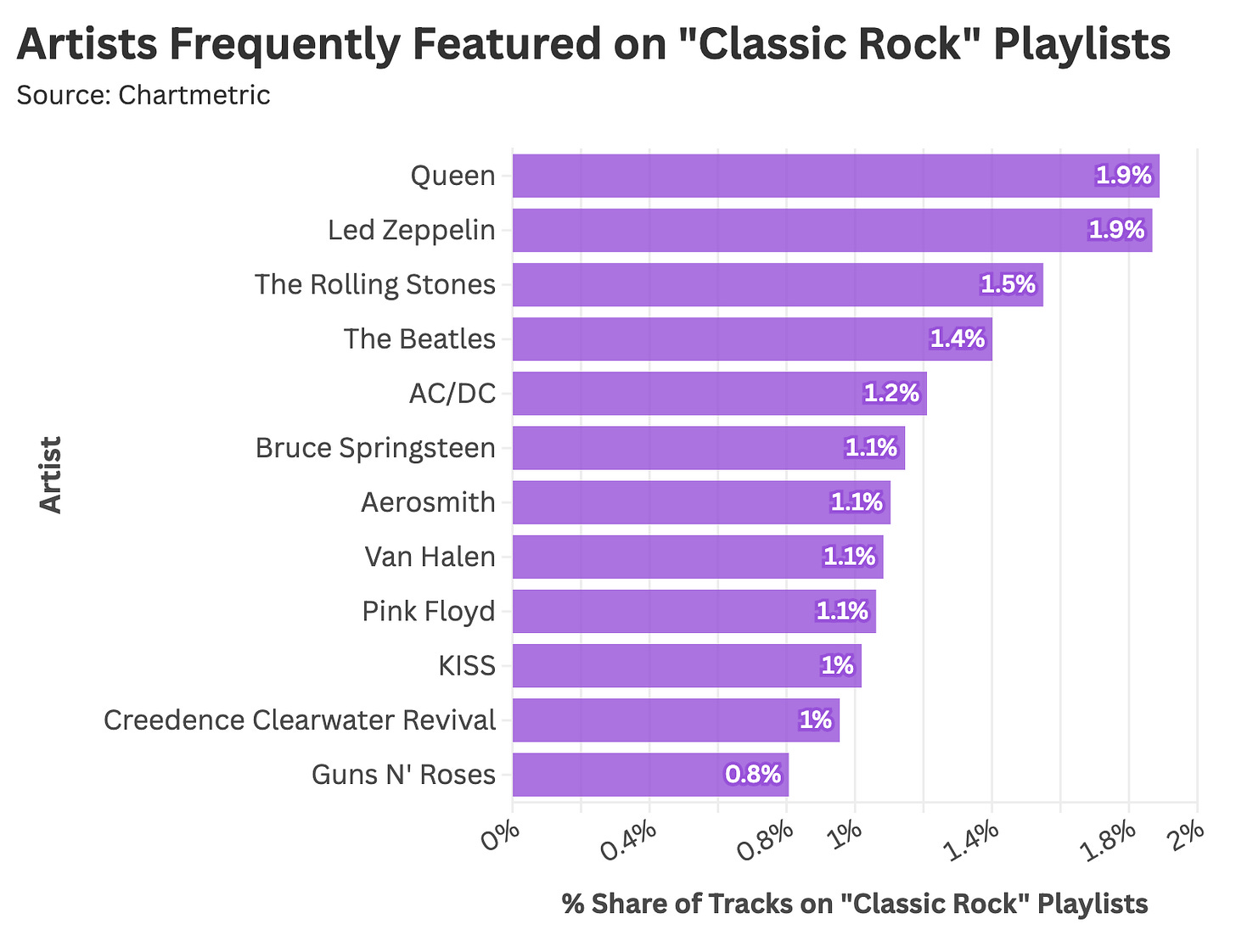

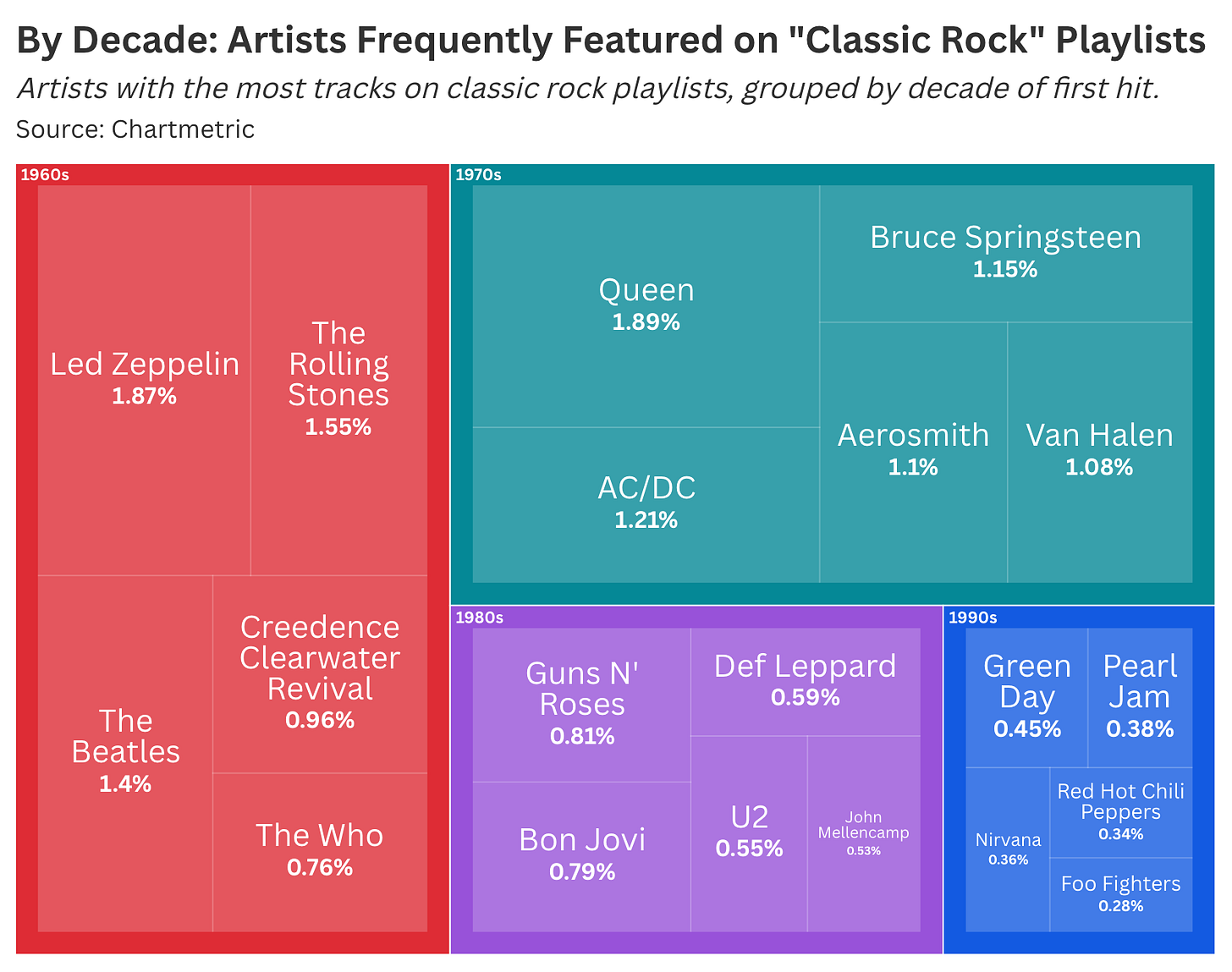

Our modern “classic rock” canon is surprisingly fluid. On Spotify’s 20 most-followed classic rock playlists, mid-century bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones appear alongside artists whose biggest hits came in the late 1980s and 1990s, such as Guns N’ Roses and Aerosmith.

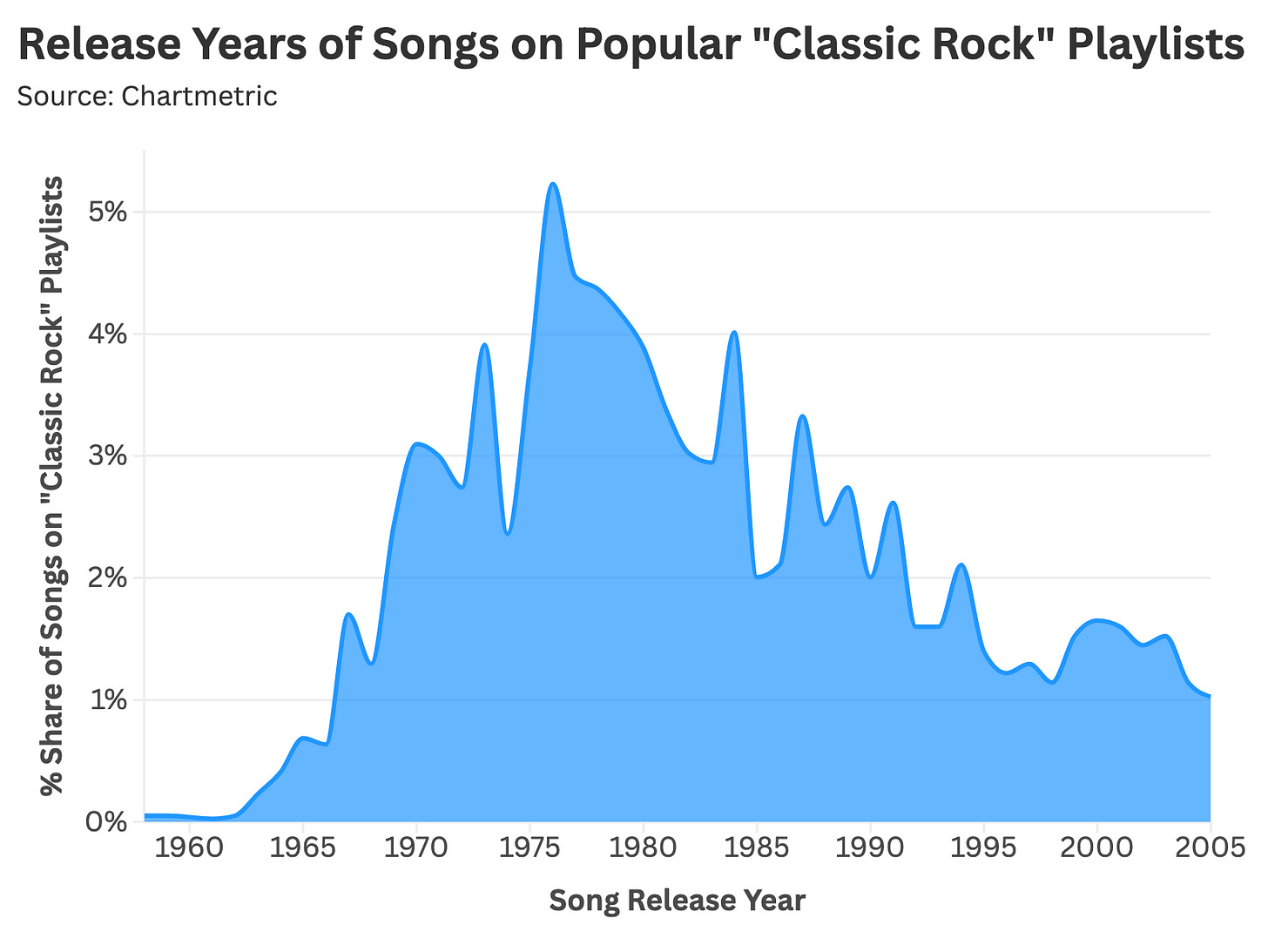

Looking at the release years of tracks on these playlists, the format peaks in the late 1970s, with a long tail extending into the mid-2000s.

Like most things forged through decentralized consensus, the boundaries of classic rock are fuzzy. Its canon is assembled less through formal criteria than by an imprecise blend of chronology and sonic similarity.

When we examine which artists appear most frequently on popular “classic rock” playlists, and group those acts by the decade of their first hit, we find contemporary bands like U2, Green Day, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers—artists with canonical “classic rock” songs released in the 1990s and 2000s.

Bands that broke through before the turn of the century—such as Green Day and Red Hot Chili Peppers—remain eligible for “classic rock” status even when many of their defining hits arrived in the 21st century. These artists emerged during a liminal period when the genre’s criteria were fluid, allowing their work to be retroactively absorbed into the canon long after its introduction. By the mid-2000s, however, that pipeline had effectively stalled. Terrestrial radio’s cultural relevance waned, rock bands stopped reaching the Billboard charts, and conditions that once enabled new entrants into the classic rock canon dissipated. Absent new inductees, the format calcified—and, in the process, became truly classic.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: Decisions Behind Closed Doors

Throughout my research for this piece, I was struck by a single nagging thought experiment: if rock music had been popularized through streaming services rather than radio, would the canonization of “classic rock” have been necessary? If The Beatles and Queen were first consumed via Spotify and iTunes, would rock have required a rebrand?

Prior to my analysis (and extensive Wiki reading), I assumed that rock’s reclassification was organic. I envisioned the term “classic rock” emerging from chaotic debate among affable music nerds—litigated on early internet message boards and in the pages of Rolling Stone or Pitchfork. Instead, what I found was a deliberate realignment engineered by music executives chasing an ephemeral advertising demographic. Like many entertainment industry decisions, it was a small (mostly male) group of executives quietly deciding the future of popular culture behind closed doors.

Stranger still, this rebrand was designed around economic incentives that have since eroded. Radio is no longer the default distribution channel for popular music, rendering advertising demography obsolete. Today’s music industry revolves around subscriptions and live performance. On streaming, music can simply exist—without having to be optimally packaged for a single, hyper-valuable consumer cohort.

Which brings us back to Bowling for Soup’s nostalgic quandary: when, exactly, did Mötley Crüe become classic rock? The answer is twofold—first in 1986, and then definitively during a concentrated wave of industry realignment between 1995 and 1998. And if the song’s protagonist were to ask a hypothetical follow-up question—like “why did this have to happen?”—the answer would be exceedingly simple: advertising revenue.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

This was a fun read. I wonder though how much of the classic rock rebranding came from stations deciding not to use the original word to market their station -- "the oldies station" -- because of Boomers' fear of aging. I remember in the 1990s the oldies stations (which played 1950s and 1960s hits, with lots of Buddy Holly, Beatles, and doo-wop) changing into "classic rock" and adding the early 1970s to the rotation. Now they were no longer old - they were "classic"!

Interesting read. I wonder why there's no such thing as "classic hip hop", "classic R&B", or "classic country". It would be interesting to see if older songs in those genres have lower radio play/streaming.