What’s the “Best” Month for New Movies and Music? A Statistical Analysis

What’s the "best" month for movie and music releases?

Intro: Dump-uary

In 1992, The Silence of the Lambs swept the Academy Awards’ most prestigious categories, winning Best Picture, Director, Actor, and Actress. Somehow, a movie about a well-educated cannibal who speaks in riddles became a commercial smash and a critical darling. The Silence of the Lambs is one of just three films to have acheived the “Big Four” Oscar sweep. It’s also the only Best Picture winner in the past seven decades to have been released in January.

If that last sentence reads like a typo, I promise it isn’t. In 100 years of this glorified popularity contest, January—a month with a perfectly normal number of days—has been bizarrely underrepresented.

In fact, anyone who follows the movie release calendar knows that January has its own nickname within the film industry: Dump-uary. Traditionally, movies perceived as having lesser theatrical appeal are unceremoniously “dumped” into the first few weeks of the year, a convenient way for studios to unload low-confidence bets from their balance sheets.

Movie releases have always been governed by intense seasonality. From Dump-uary to summer blockbusters to prestige Oscar fare, conventional wisdom holds that different parts of the calendar are best suited to different kinds of films.

Hearing my favorite movie podcasters (once again) complain about this year’s Dump-uary slate got me thinking about two completely unrelated questions. First: Is this phenomenon quantifiable? And second: Does the same logic apply to the music industry? Are pop stars constrained by seasonal demand in the same way—or can musicians release albums whenever they want because nobody cares about the Grammys?

So today, we’ll explore the best months to release new movies and music, the strange seasonal rhythms of how music is consumed throughout the year, and how streaming has reshaped music’s role in our daily lives.

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by The Stat Significant Dataset Hub

Access 190+ Curated Datasets to Elevate Your Analysis

Want the data behind the deep dives? The Stat Significant Data Hub gives you access to 190+ curated datasets spanning movies, music, TV, economics, sports, and more.

New datasets are added weekly, with full archive access for Stat Significant paid subscribers. Since last week’s post, we added 11 new datasets—covering everything from global aviation accidents to Amazon product records to historical baseball statistics.

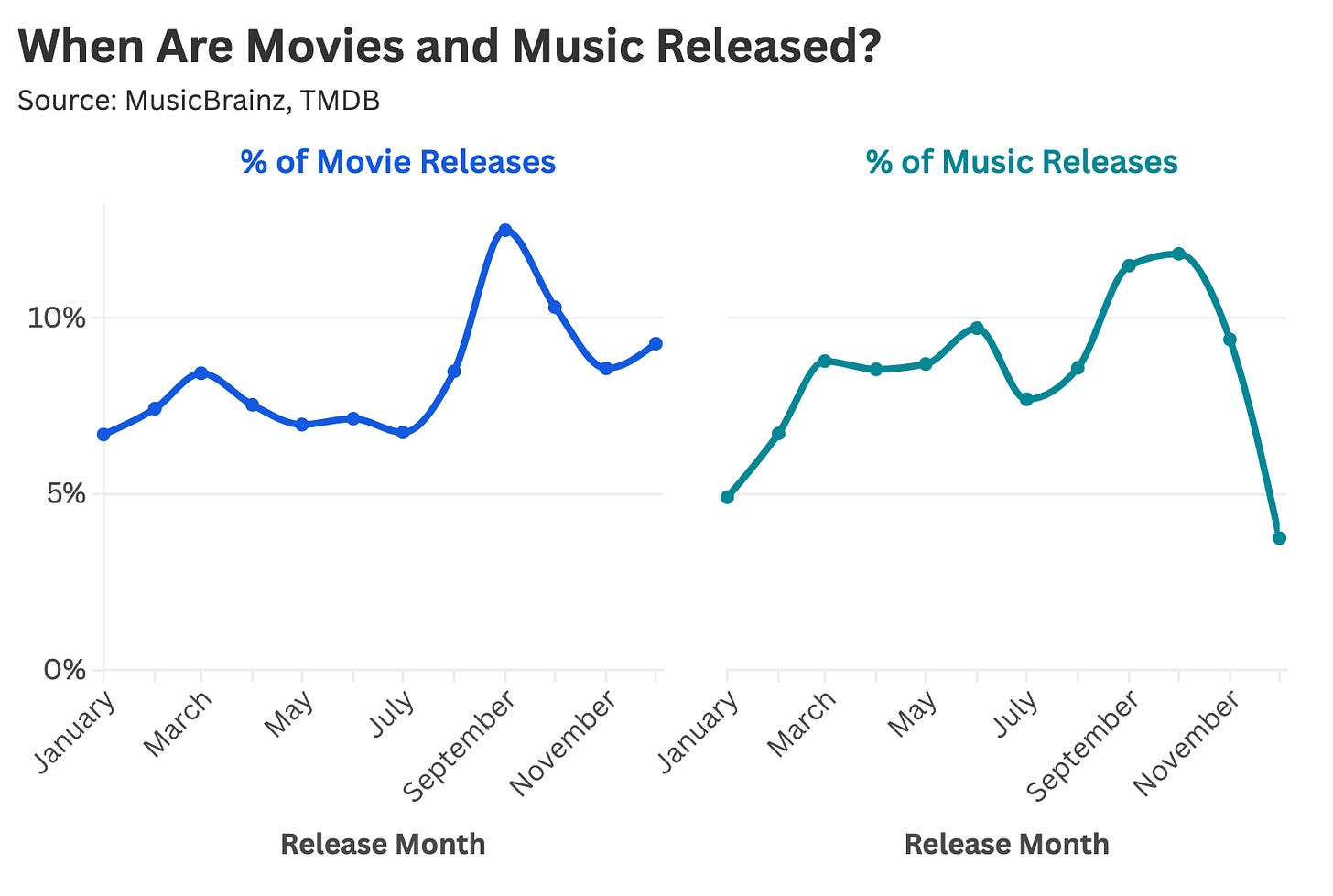

When Are Movies and Music Typically Released?

Releases tend to be weighted toward the back half of the year for both film and music. Both industries see upticks in distribution in September and October, followed by a steep drop-off in November and, for albums, in December.

This data corroborates the Dump-uary phenomenon, with January consistently posting the fewest film releases. By volume alone, it’s a bad month for da’ movies.

Part of the fun of writing this newsletter is perpetual discovery. Despite producing ~150 artisanal essays on the facts and figures underlying popular culture, I am still consistently wrong (which, depending on how you look at it, is either sad, comforting, character-building, or a combination of all three). With most analyses, I have a directional sense of which way the results will go. But not with this one. My initial findings were nowhere near expectations. Why would summer see fewer movie premieres if that’s when all the blockbusters debut? Why are fewer albums dropped in December if that’s when people buy the most stuff?

To demystify these patterns, I first dissected the film industry’s fairly intuitive release schedule before digging into the wacky world of music distribution and consumption.

The Ups and Downs of the Movie Calendar

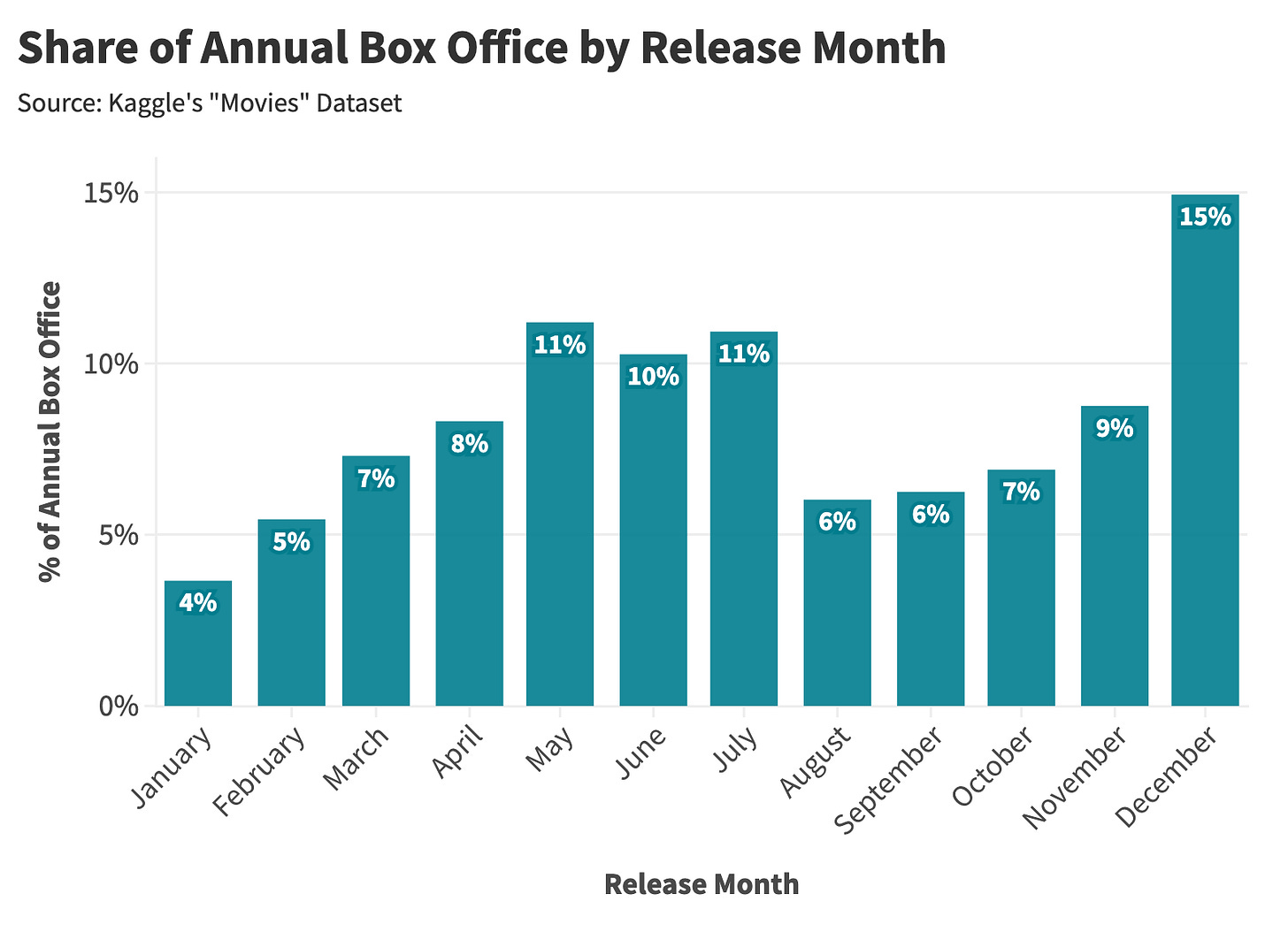

Seeing a movie requires free time. Between ever-lengthening trailers, a rogue Nicole Kidman AMC ad that is long past its cultural expiration date, and the simple fact that movies themselves keep getting longer—the time commitment is no joke. In practice, this means movie viewership, as measured by share of box office, is weighted toward the summer months and holidays when children and parents have ample time.

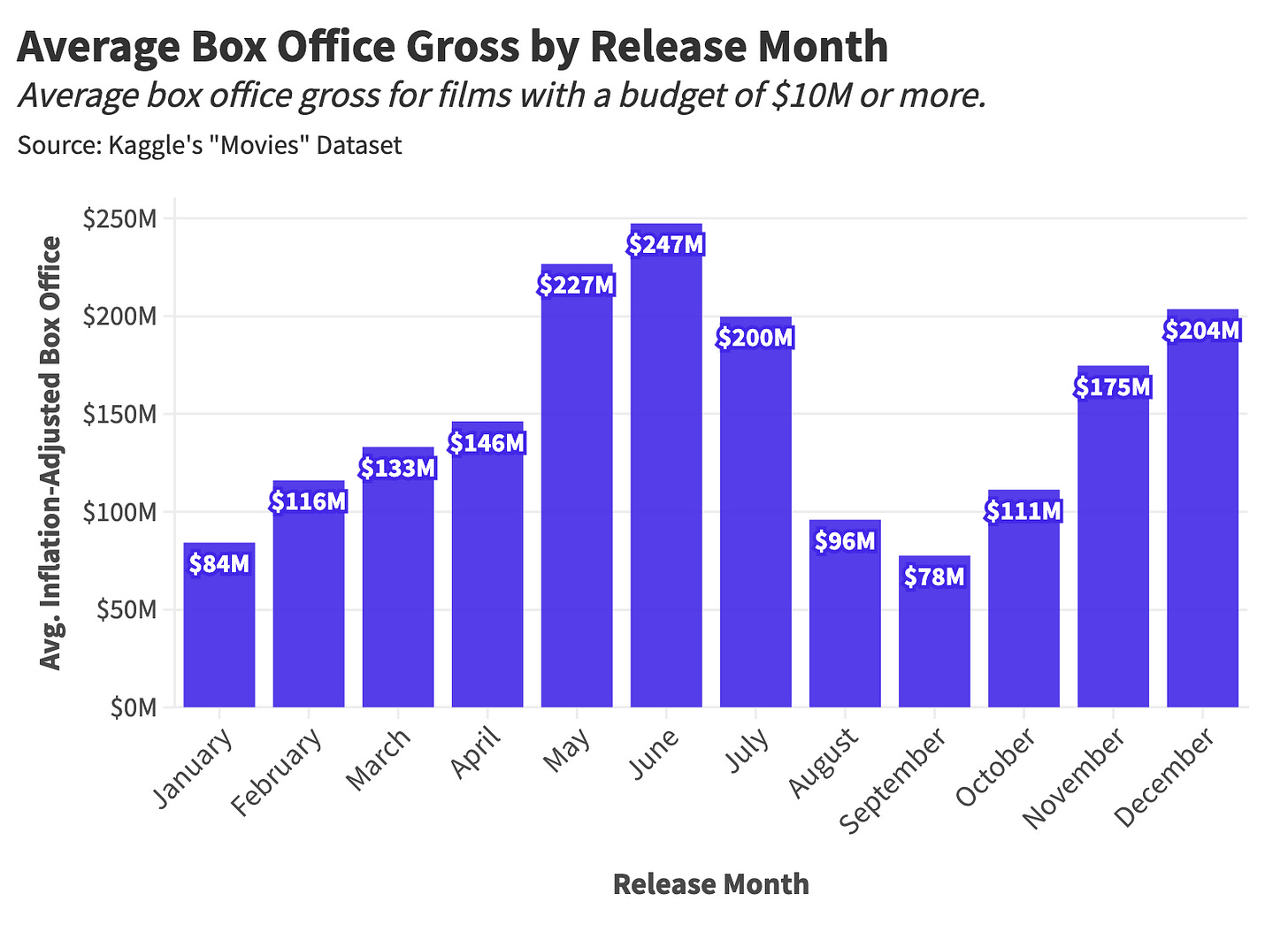

If audiences are more likely to buy tickets in the summer, why are fewer films released during this window? The answer, as is the case with all totally-awesome things in life, revolves around profit maximization. Periods with elevated total box office are also those with higher per-film grosses, as studios chase the elusive mega-billion-dollar hit.

As of this writing, Dune: Part Three and Avengers: Doomsday are scheduled to come out on the same day. Unless a Barbenheimer-esque crossover occurs, it’s likely that one of these studios will acquiesce and change release dates, allowing both movies greater runway to make lots of money. Yay money.

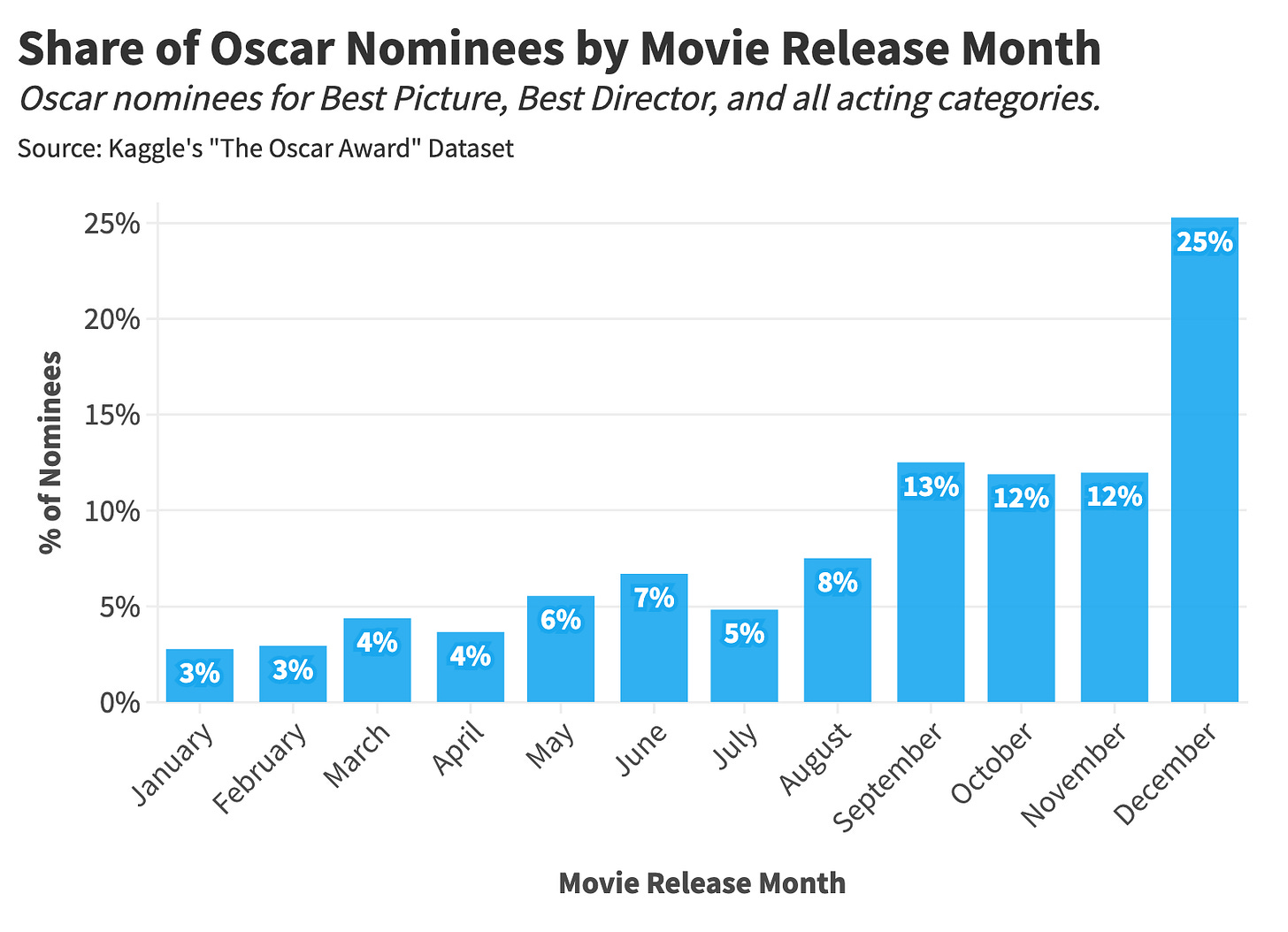

Blockbuster cultivation explains the drop in summertime releases, but what drives the uptick in October and November premieres? Why, the Oscars, of course! I have dedicated two articles to the Oscars, and, consequently, these are my two worst-performing pieces because most people do not care about the Oscars. Or do they?

While fewer people tune in to the Oscar broadcast, curiosity about what gets recognized remains strong. An Oscar nomination still confers cultural legitimacy—and, crucially, delivers a measurable boost at the box office and on streaming platforms.

As a result, studios cluster their Oscar hopefuls into the back half of the calendar, ensuring these films are fresh in voters’ minds when awards season commences in early January.

The Oscars offer an economic lifeline to mid- and low-budget films, prompting a surge of prestige releases in the latter half of the year. These films are then kept in theaters deep into the new year to capitalize on awards buzz, crowding out space for new releases. The result: fewer January debuts, making Dump-uary even more dump-ier.

The Wacky World of Music Distribution and Streaming

Music consumption does not require ticket fees, parking, Nerds Gummy Clusters, or a Nicole Kidman promo. With a streaming subscription, accessing music is as simple as opening Spotify—or turning on your car.

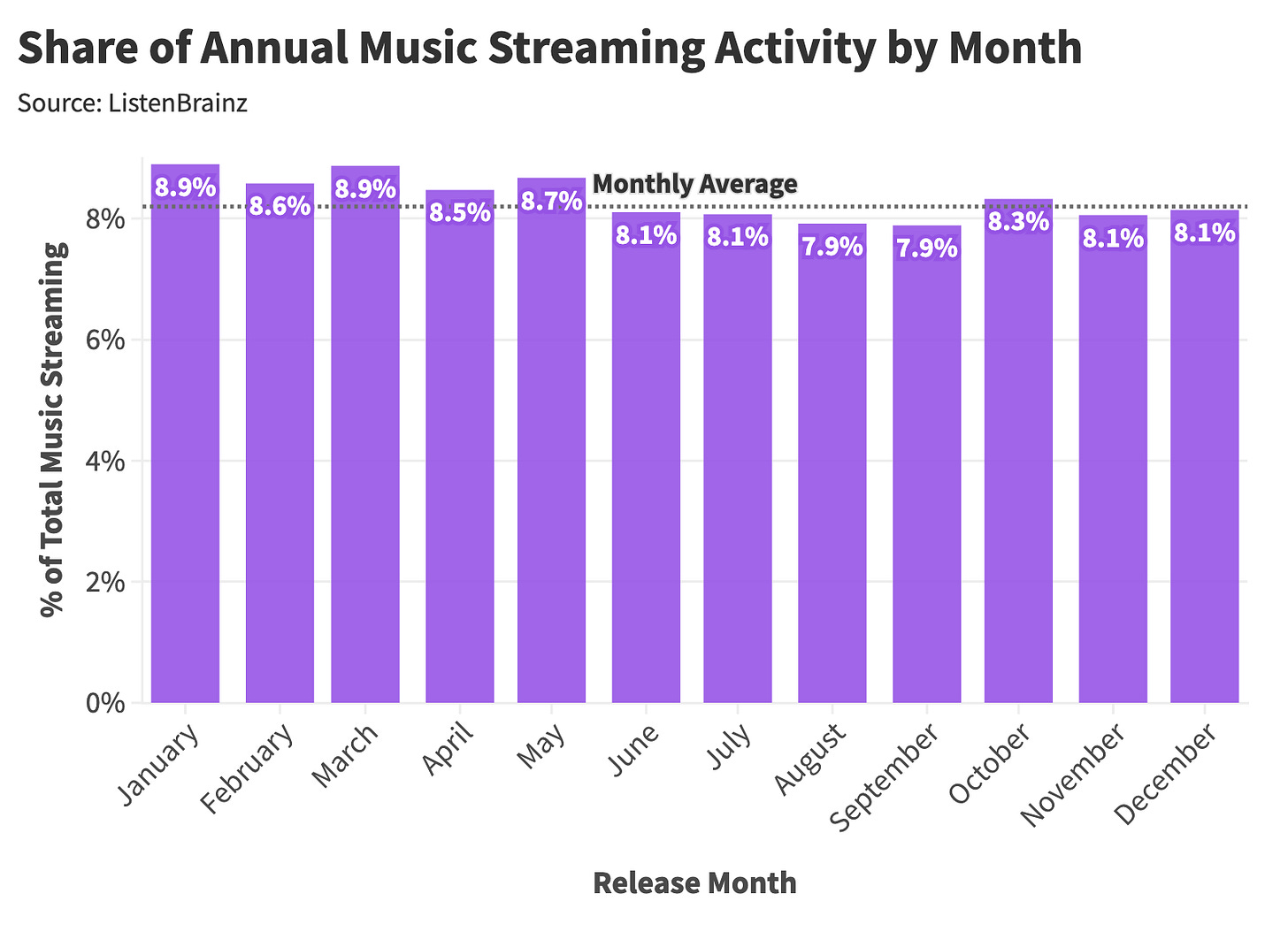

As a result, streaming activity shows far less seasonality throughout the year, with only a modest decline beginning in the summer months.

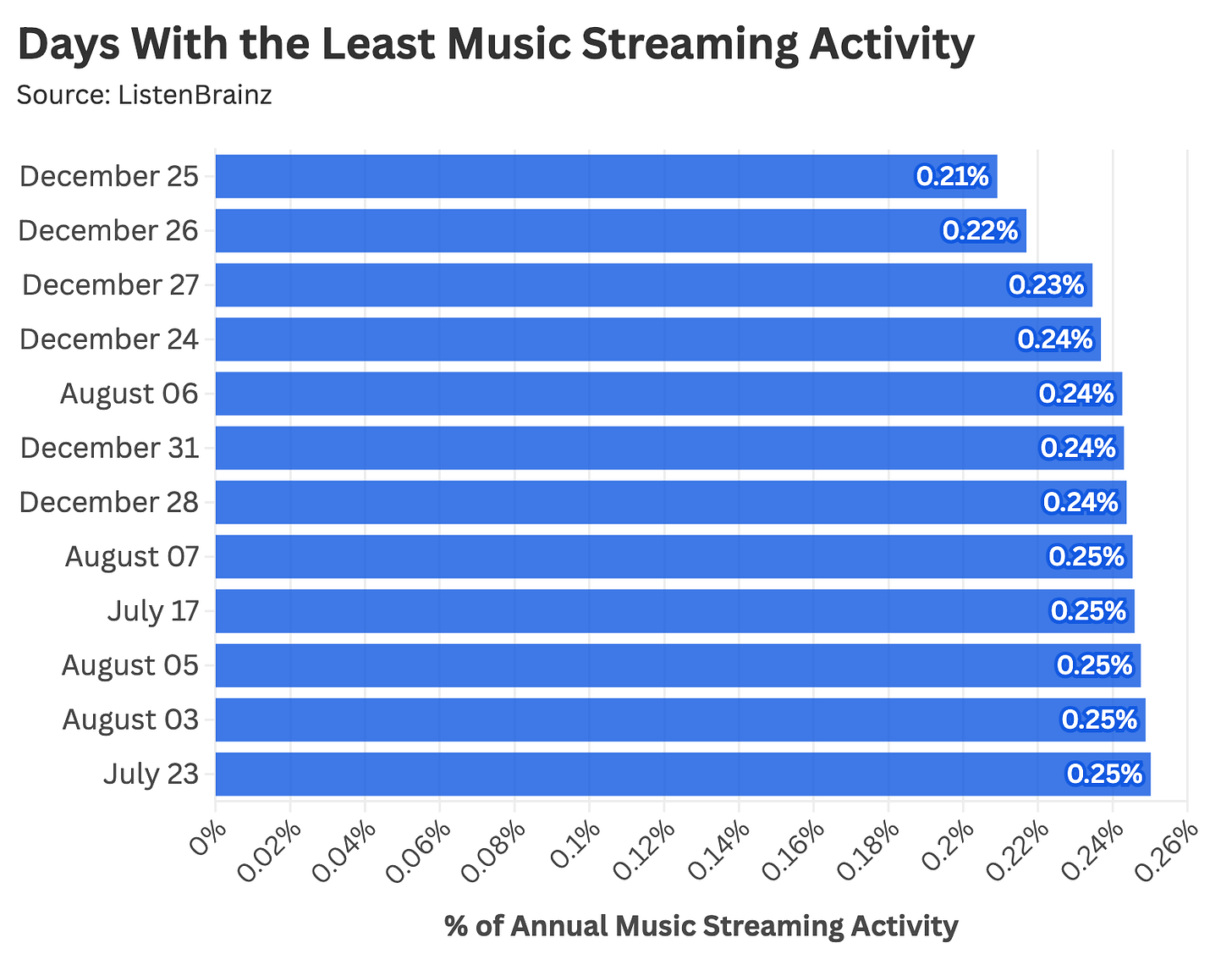

I found the relative year-end dip in streaming particularly striking, given that this period coincides with an increase in album releases. If more music is being released, why is less of it being played? The answer, it turns out, has less to do with song supply and more to do with how people spend their time.

When we examine the days with the lowest streaming activity, we find a mix of major holidays and peak summer dates. People don’t listen to music during Christmas or on vacation because they’re too busy spending time with their family and going to the movies. How wholesome.

In fact, the single strongest predictor of when people listen to music is decidedly mundane: work.

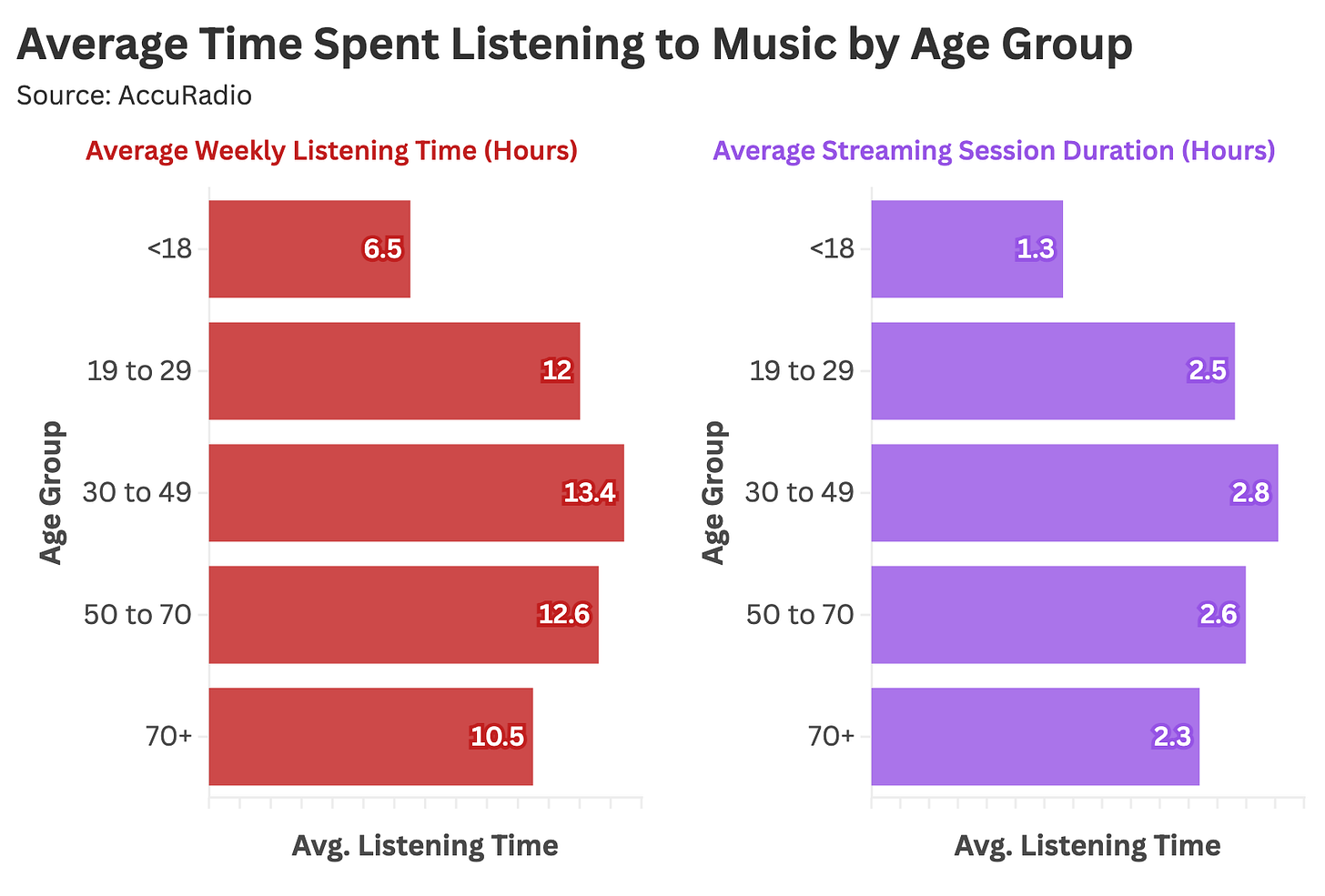

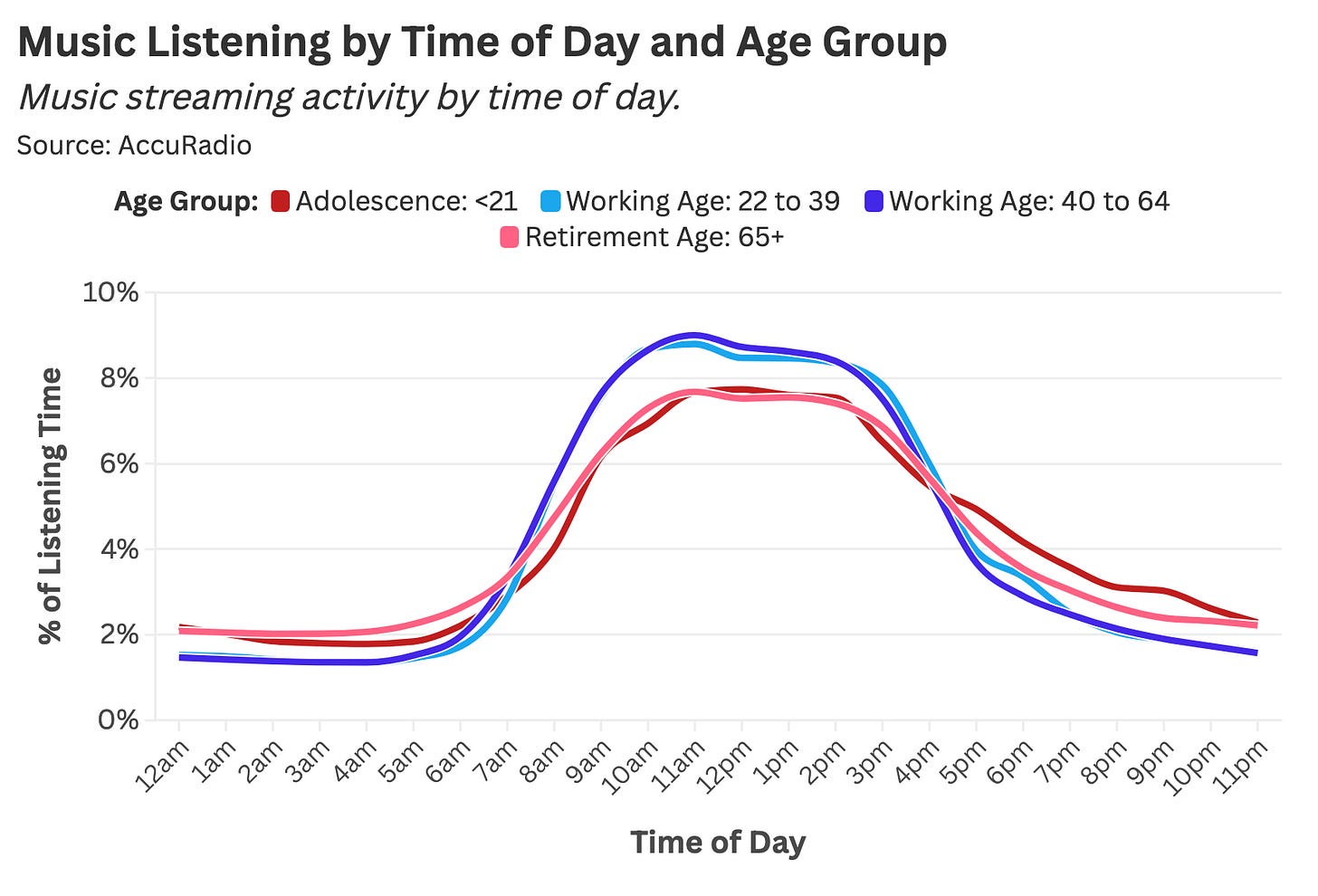

On a week-to-week basis, listeners aged 30 to 70 spend more time on streaming platforms than younger and older cohorts.

How is this possible? Don’t tweens and teens spend hours discovering new music, while thirty-somethings slowly wither at their desks, intermittently checking Kalshi for real-time odds of an AI apocalypse?

The answer is yes—to all of the above. But the monotony of adult life introduces several situations in which streaming platforms like Spotify, Pandora, and AccuRadio become indispensable:

Commuting

Being bored at work

Drowning out loud coworkers

Long work bouts (coding, writing, strategizing, etc.)

Trying to inject joy into your day while doing activities 1, 2, 3, and 4, as well as all the time in between

Working-age groups (highlighted in blue) exhibit a higher proportion of their music consumption during work and commuting hours, whereas adolescents and retirees are more likely to stream at night.

Nothing screams adulthood like listening to Green Day’s “American Idiot” whilst prepping tax documents or forecasting Q3 revenue.

Music’s role in our lives shifts dramatically with age. It begins as a tool for identity formation and cultural exploration, then evolves into a practical aid for getting through the workday, before eventually returning to its purest role: entertainment.

So how do these age-specific listening patterns influence album release timing? The answer centers on the birth of a new phenomenon, which I will call Dump-cember.

Artists are far less likely to release new music in December, when overall listening declines and year-end attention is monopolized by Christmas classics. The September–October uptick in album drops appears to be a deliberate attempt to avoid the holidays—maximizing the odds that a new record gains traction without seasonal interference.

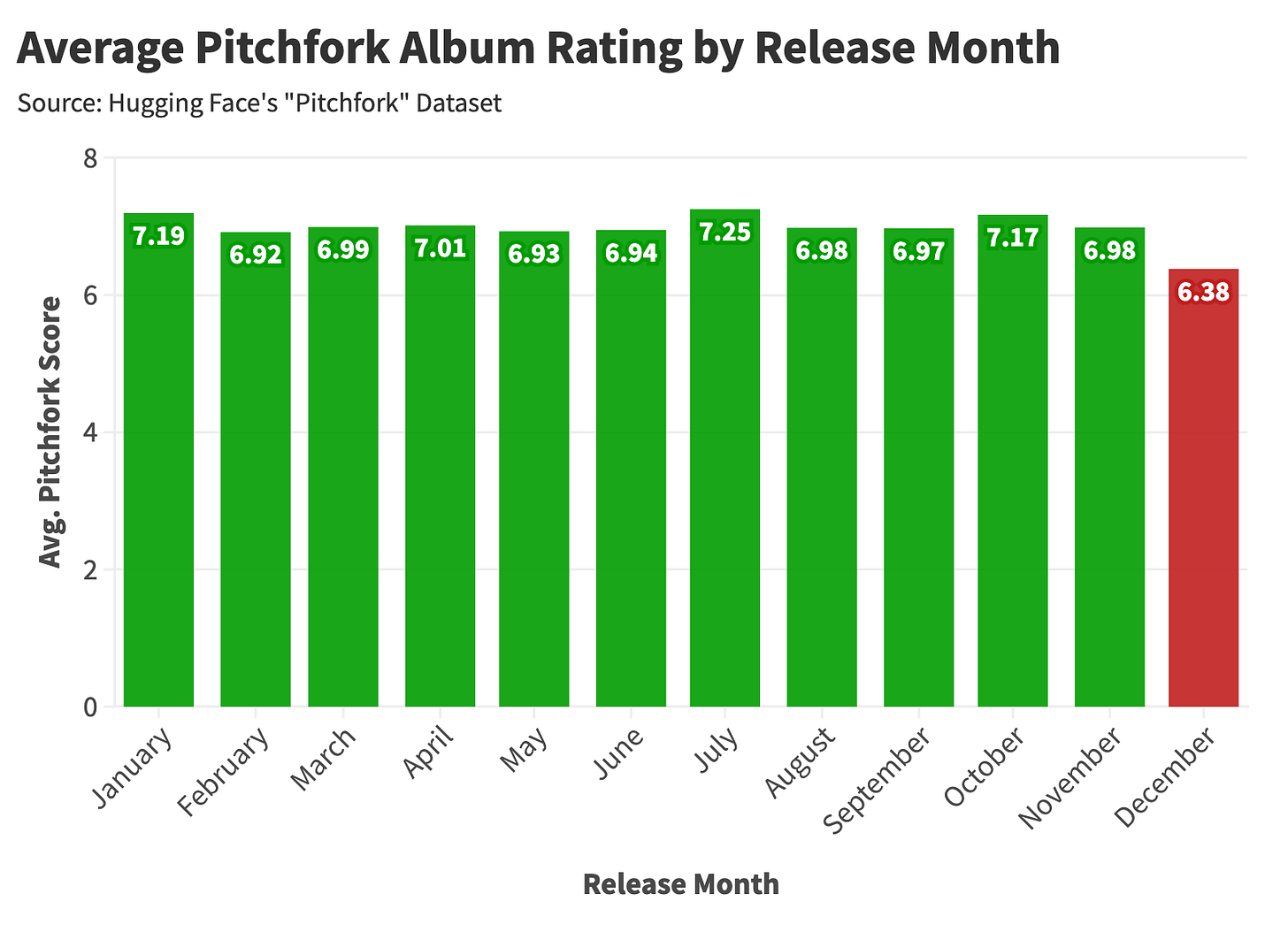

If Sabrina Carpenter or Bad Bunny drops an album in early December, they will be competing with Christmas staples from Bing Crosby (“White Christmas”) and Andy Williams (“It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year”), who have been dead for decades. The result is a thinner release calendar and a higher share of low-profile albums, which tend to receive weaker critical reception, as measured by Pitchfork scores.

This pattern reflects a mix of critical fatigue and strategic distribution: critics tend to dismiss trend-chasing holiday releases, while labels quietly slot their least promising projects into a low-attention window.

There is no “best” month to release new music—most months are interchangeable—with the exception of December. December is bad; everything else is the same. With that insight, I hope to cement my eternal online legacy as the person who quantified and coined the term Dump-cember. Dad, if you’re reading this—I hope you’re proud.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: Consider the Lightbulb

When I was a kid—and even later as a film student—I thought art simply existed, summoned at the whims of temperamental geniuses. I assumed artists only stopped working to chain-smoke cigarettes, decry the pitfalls of commercialism, and brood at their muses.

As an adult, I’ve learned that mass-disseminated art depends on capital investment, and its distribution is often shaped—quite bluntly—by return on investment. Through this lens, it’s easy to grow cynical about capitalism’s influence on culture, until you realize we live in an era where entertainment is endlessly accessible, perhaps even overwhelming in its abundance.

For most of human history, that abundance simply wasn’t possible. Before climate control, electricity, audio recording, film production, the internet, Napster, TiVo, Quibi, Hulu, and Tubi, one’s engagement with art was dictated by the seasons:

In 5th-century Greece, cultural life was compressed into events like the City Dionysia, a spring festival held after the harvest that often premiered new plays.

The Roman Empire’s Ludi Romani occurred in early September, blending gladiatorial games, musical celebration, and theatrical performance.

Shakespeare’s plays largely ran in the summer months, when daylight was plentiful, and his shows were frequently interrupted by plague outbreaks.

Before temperature control and lightbulbs, there were predictable periods when art flourished and long stretches when it simply couldn’t.

Today, those constraints are gone. If anything, our most recent global pandemic demonstrated the opposite: media consumption surged as streaming filled newly found hours. Say what you want about Ted Sarandos (Netflix’s co-CEO), but the man gives us no shortage of content. Whether this content qualifies as art is a matter of opinion.

Having conquered the elements, the foremost determinant of entertainment consumption is free time. With less leisure time, you’re more likely to listen to music; with ample hours, you can commit to TV and movies.

In the modern era, every day is City Dionysia and Ludi Romani, with the exception of Dump-uary, and, of course, Dump-cember.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

Nicely done. For a moment I thought I was reading a more in-depth Ted Gioia Substack, which I mean as a compliment. Bravo.