Hollywood’s Music Biopic Boom: Quantifying the Rise of a Soulless Genre

How music biopics overtook Hollywood.

Intro: Contractually Obligated Viewership

Culture comes for all of us if given time. When enough people like something—say a movie or book—that appreciation becomes an asset. What does this mean in practice?

If you liked The Devil Wears Prada, then you’ll soon be purchasing two tickets for the long-awaited sequel (coming in May 2026).

If your favorite Batman character is The Penguin, then you’re locked into a gritty HBO miniseries where the third-best Batman villain is now a relatable anti-hero.

If you love Emojis, then you were there for opening weekend of The Emoji Movie (which currently holds a 6% on Rotten Tomatoes).

I’ve long observed this process from a distance: a reboot or adaptation gets announced, longtime fans respond with a mix of frustration and resignation, and I watch the whole thing unfold with detached curiosity, thinking, “Glad that’s not me!”

And then I saw a trailer for Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, a dramatization of Bruce Springsteen’s efforts while recording his 13th-best-selling album (Nebraska). My dad loves Bruce Springsteen, which means I love Bruce Springsteen, which means I’m now contractually obligated to watch a music biopic that’s likely to fall short of my expectations. Culture has come for me—and for my love of “Born to Run.”

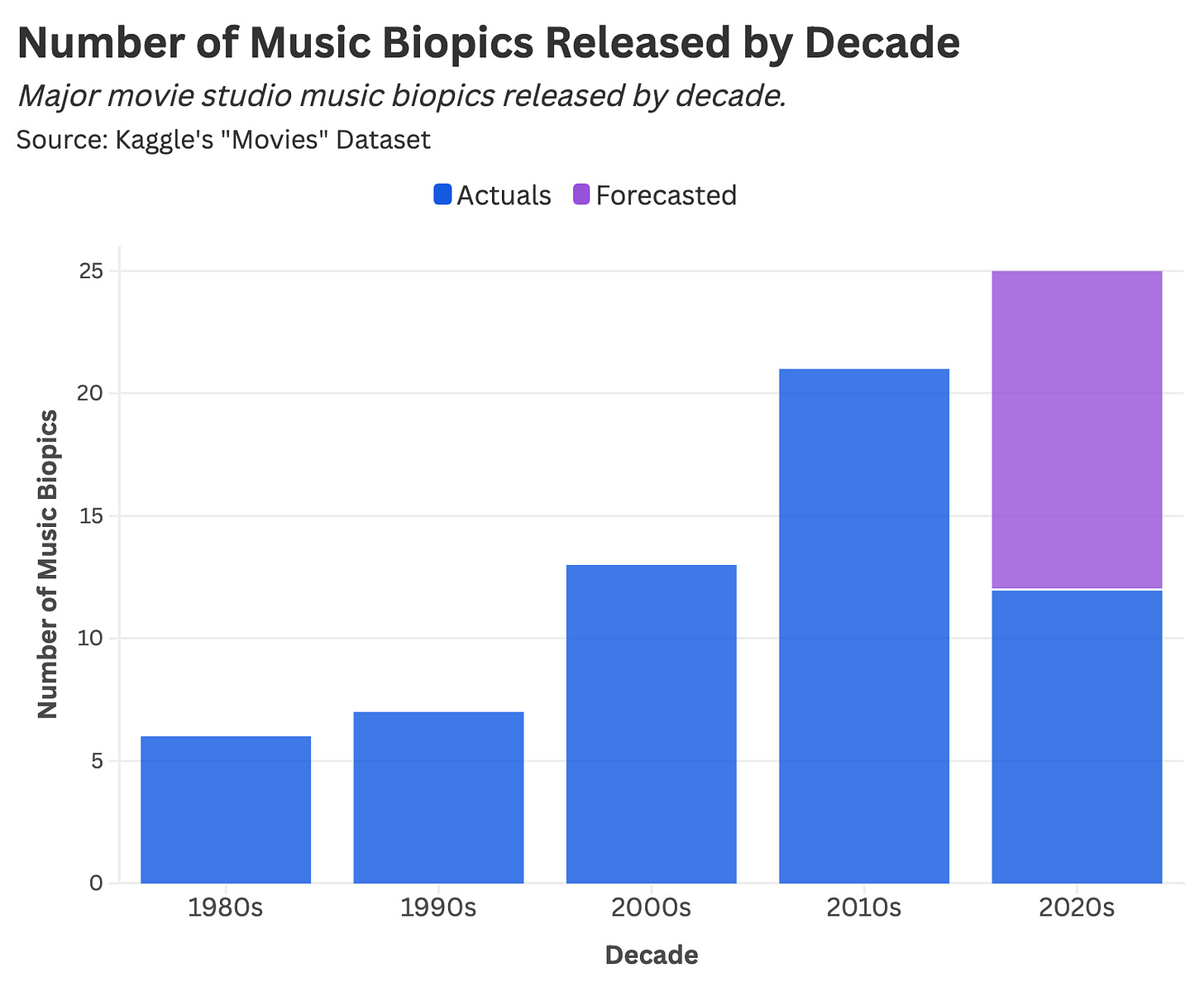

The past decade has seen a glut of Hollywood films dedicated to the lives, songs, and struggles of musicians who mostly overcame those struggles—because why else would this movie exist? Some recent examples include: Bob Marley: One Love, Bohemian Rhapsody, Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody, Elvis, and A Complete Unknown. We get two to four music biopics a year, and for the most part, I’ve managed to steer clear. Until now.

It’s with this in mind that I went to my local AMC theater to watch a film with no narrative stakes about a cultural icon who succeeded so thoroughly that they decided to make a movie about it. I should also say that I had a decent time (because I love Bruce Springsteen).

So today, we’ll explore the rise of music biopics, why this format is uniquely successful despite its formulaic nature, and the economic incentives that have fueled its proliferation.

What Makes Music Biopics So Profitable, So Predictable, and So Prevalent?

My screening of Springsteen [Colon] Deliver Me From Nowhere is sold out at 3:15 on a Friday, packed with diehard Bruce fans and, for ten minutes, someone who wandered into the wrong theater.

As I take my seat, I hear the couple behind me discussing an upcoming biopic on totally-not-controversial-king-of-pop Michael Jackson, which will be released next year. My best guess is that this film will omit some crucial aspects of Michael Jackson’s legacy and will also make hundreds of millions of dollars. You know why? Because people love music biopics—and Hollywood has met this ample demand by releasing movies about Amy Winehouse, Bob Marley, Bob Dylan, Robbie Williams, and Bruce Springsteen in the span of 20 months.

Buoyed by the success of blockbusters like Ray and Walk the Line, music biopics saw a sharp rise in production starting in the early 2000s.

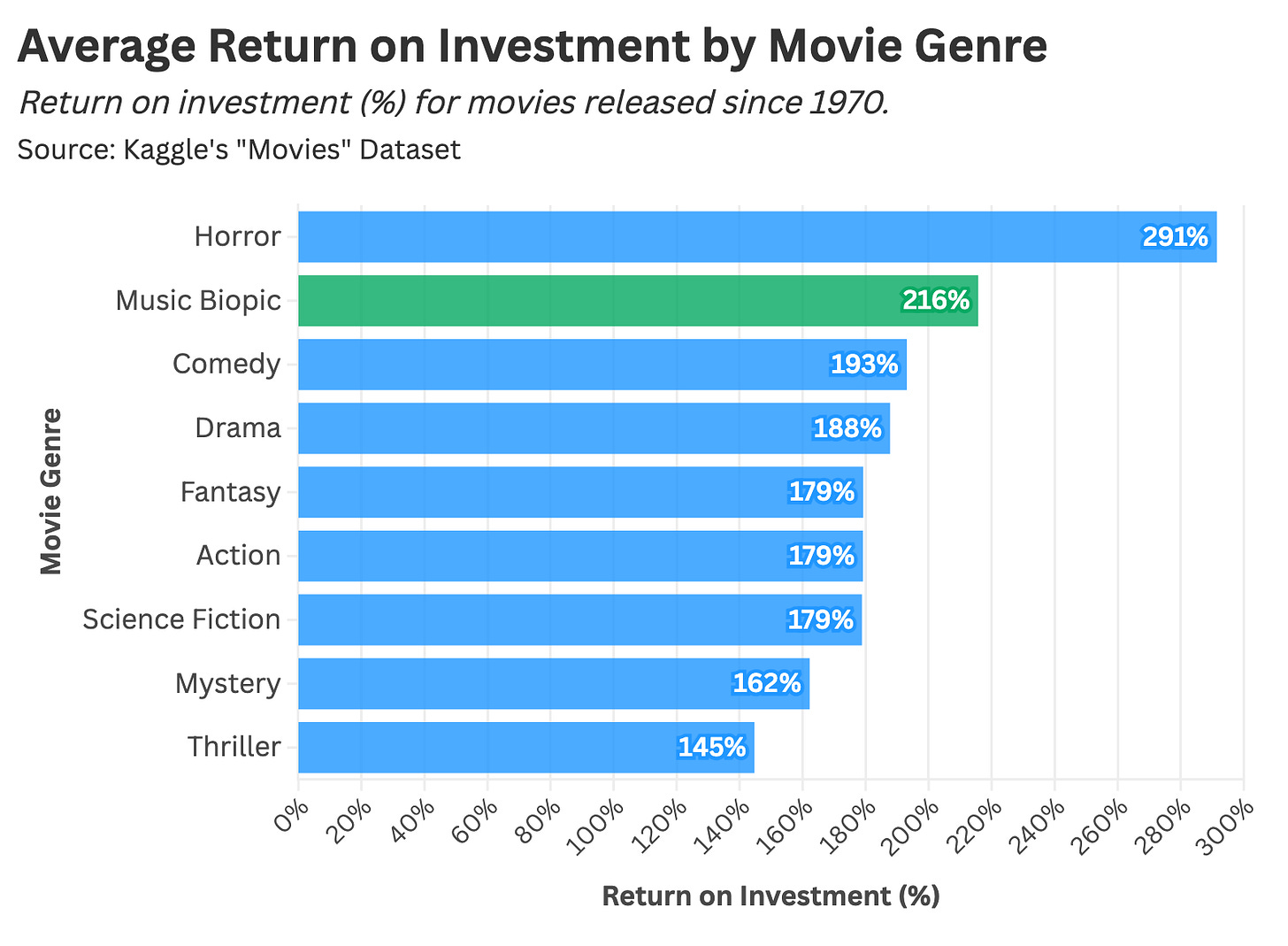

To say the quiet part out loud: these movies are quite profitable. The average music biopic has a return on investment comparable to that of a horror movie, which is why these two formats seemingly account for ~50% of Hollywood box office.

As a change of pace, Springsteen—Colon—Deliver Me From Nowhere is projected to be a box office bomb due to its focus on a less popular Springsteen album. I maintain that if they called this movie Springsteen: Born in the U.S.A. or Born to Run (Whichever One You Like Best), it would have seen Avatar-level grosses.

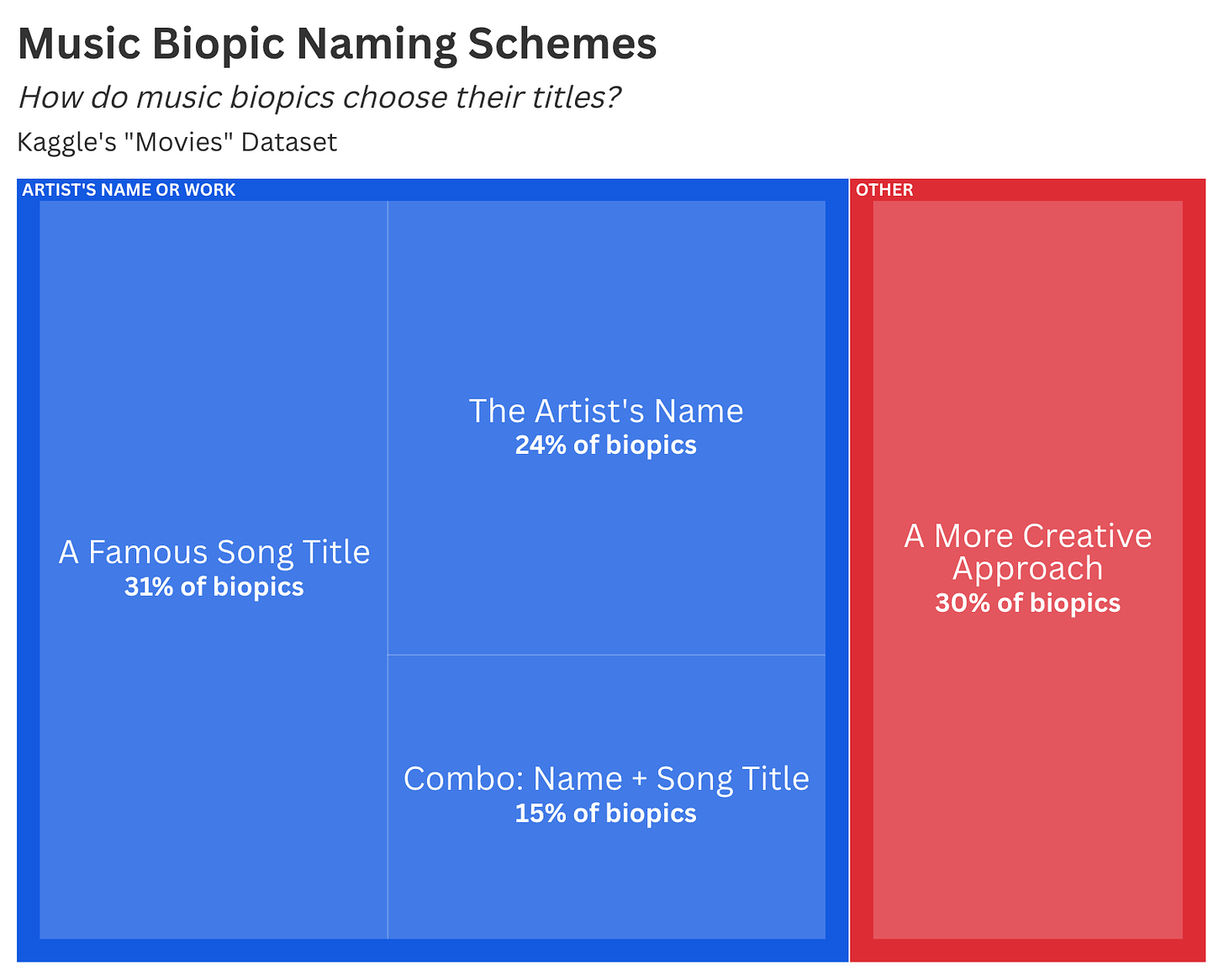

Which brings us to the topic of movie titles. Biopic names typically fall into one of four buckets:

Referencing a famous song: Respect, Bohemian Rhapsody, Walk the Line

Referencing the artist’s name: Amy, Ray, Amadeus

Referencing a combination of artist name and song: Bob Marley: One Love, Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody

Genuine creativity: Control, 24 Hour Party People, Behind the Candelabra

To quantify this paint-by-numbers approach, I categorized each biopic by naming convention. I found that ~70% use some combination of artist likeness and a signature song, which is lower than I expected.

The goal of movie marketing is to make sure audiences know what they’re getting. From this vantage, invoking the musician’s name and art leaves little room for misinterpretation. The Bob Marley movie is about Bob Marley, and you will probably hear the song “One Love” while watching this film. If you’re still confused after reading the title Bob Marley: One Love, then those marketing dollars have been wasted on you.

In the case of Springsteen [Colon] Deliver Me From Nowhere, the title is a combination of the artist’s name and a reference to a song that does not exist. I do not understand why a studio would spend $55M on this film and not name it Springsteen: Glory Days + Dancing in the Dark. If you’re going to be formulaic, then be formulaic!

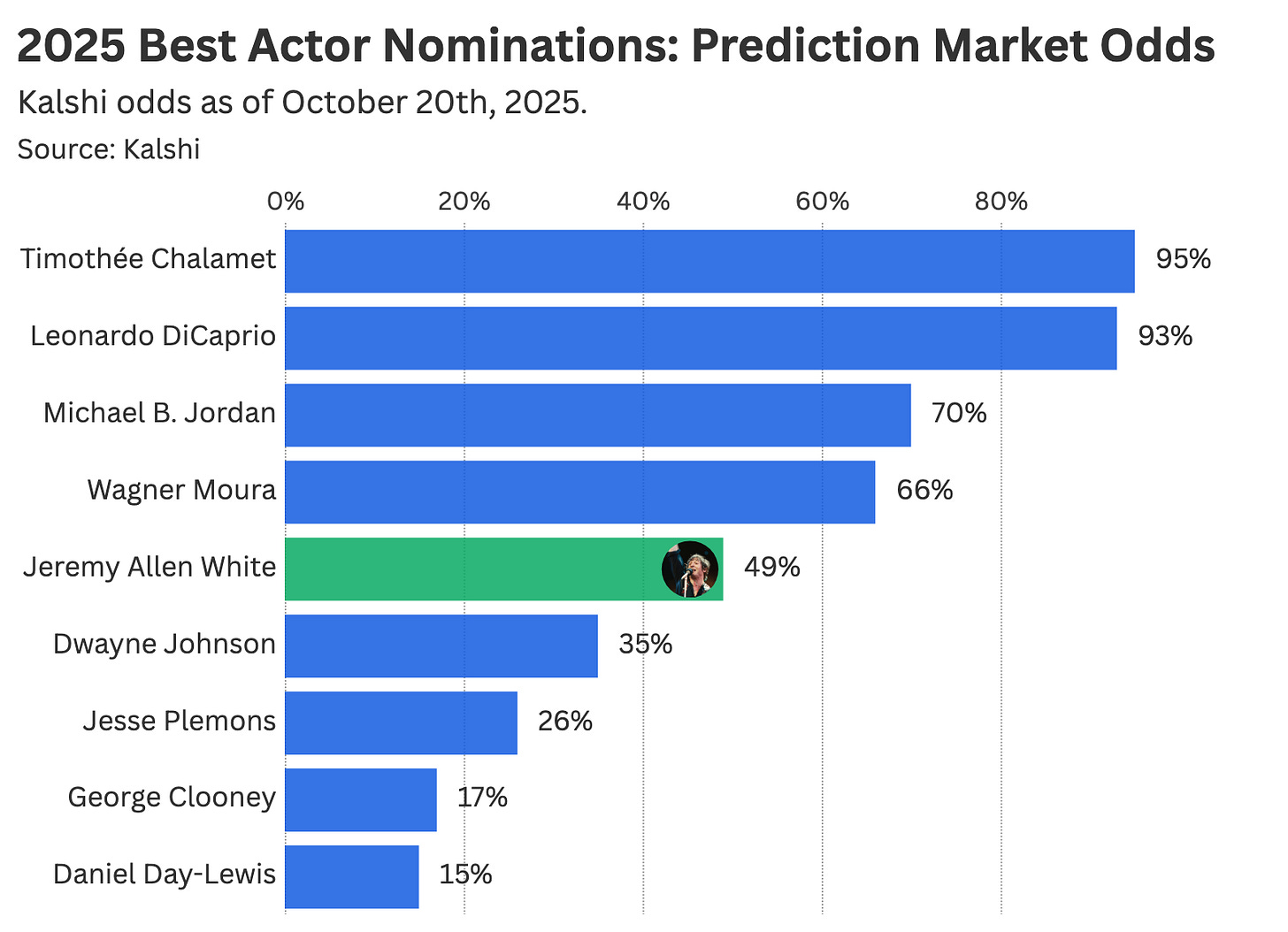

Perhaps this bizarre naming scheme stems from the film’s focus on a lesser Springsteen album that lacks an identifiable hit. If that’s the case, then the primary motivation for seeing the movie is mimicry. You like Bruce, and you want to see up-and-coming actor Jeremy Allen White do his best Springsteen impression.

One of the enduring appeals of the biopic—musical or not—is cosplay. A poster declares “Naomi Ackie is Whitney Houston” or “Jamie Foxx is Ray Charles,” and suddenly I want to see if they can pull it off. My lizard brain is hard-wired to enjoy actors impersonating cultural icons. Show me Rami Malek pretending to be Freddie Mercury, and I’ll react like the meme of Leonardo DiCaprio pointing at something, because that’s human nature.

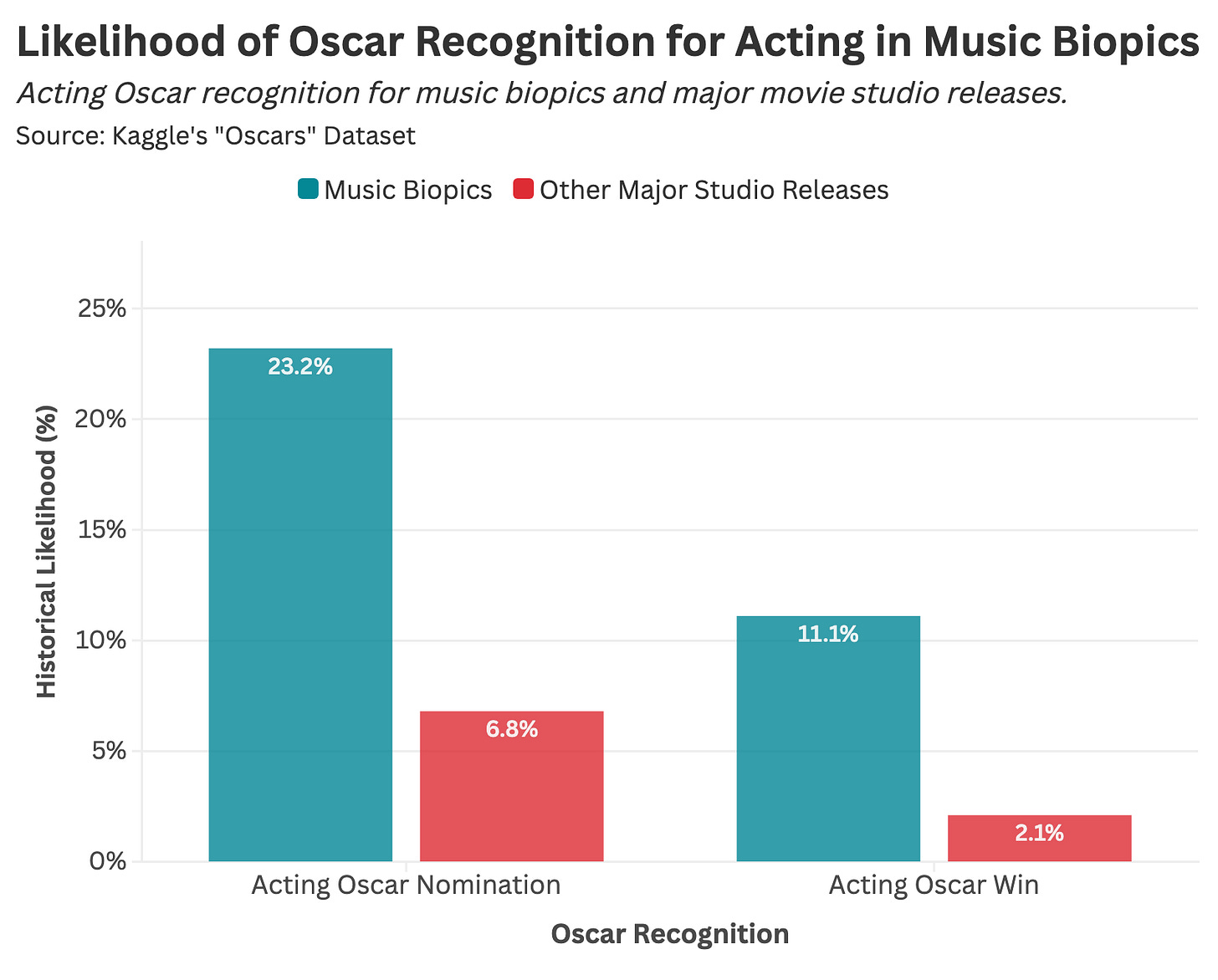

This impulse is universal, which is why biopics usually qualify as Oscar bait. Suppose the actor learned to sing like Aretha Franklin or David Bowie: they will garner a 26-minute standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival (meaning the movie was slightly above average) and receive a nomination for Best Actor.

Historically, nearly one in four of these movies receives an acting Oscar nomination, and one in nine actually wins an award.

Academy voters are (a) aware of this pattern and (b) apparently don’t care if they’re being predictable. If someone can do a credible M.C. Hammer impersonation, then they will be nominated for their work in M.C. Hammer: U Can’t Touch This.

As of last Monday, betting markets project Jeremy Allen White will be nominated for Best Actor. After all, he kinda sounds and looks like Bruce, and he learned to sing and play guitar!

I’ve always been ambivalent about these performances. Biopic actors put a lot of effort into their mimicry, but they also don’t have to create a character from scratch. Clearly, mimicry trumps originality and constructed interiority.

But Oscar nominations and box office are only part of the motivation for these movies. Perhaps their real value lies in reigniting public interest in an artist’s career.

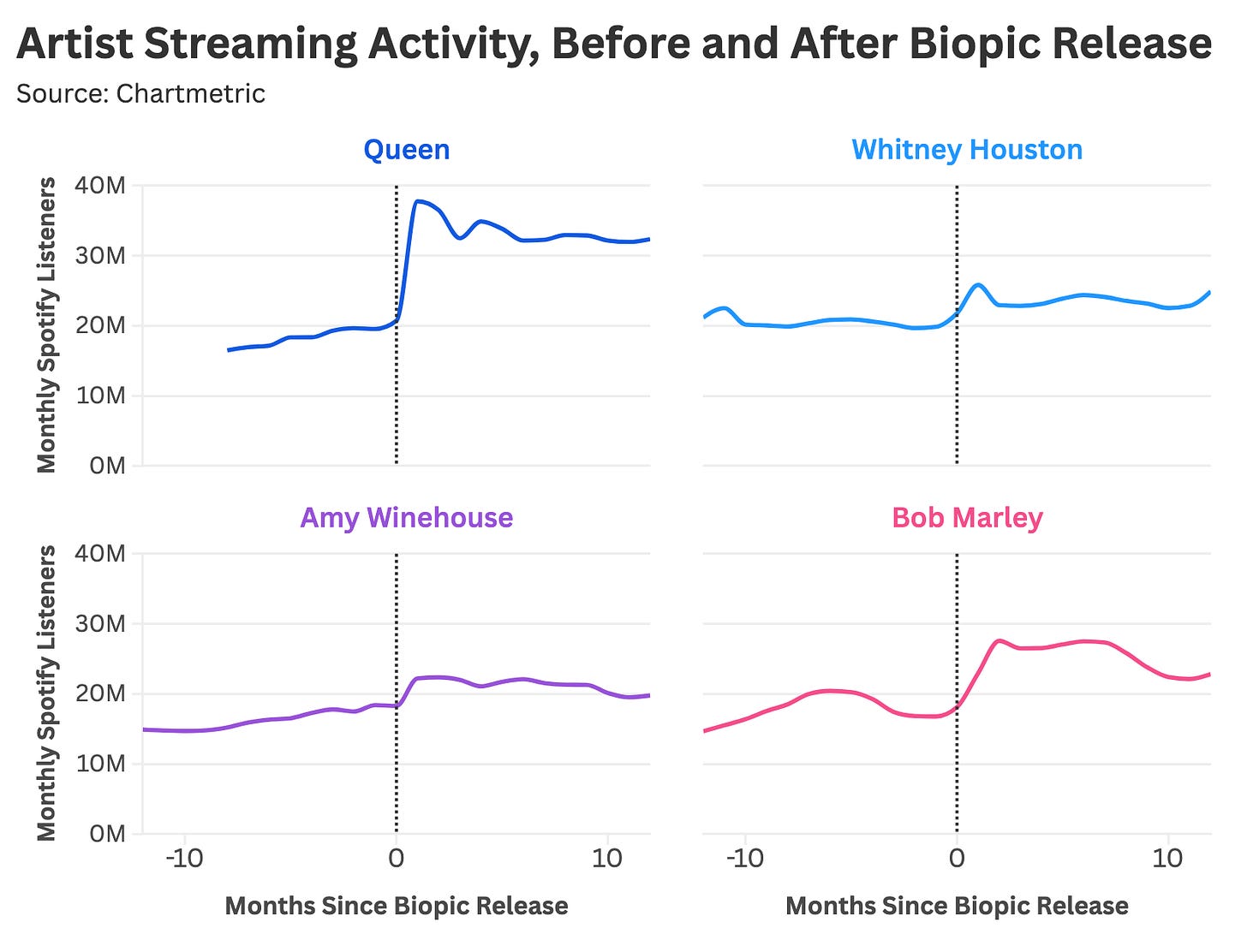

Music biopics typically lead to a sustained boost in monthly listenership for their subjects. A poorly received biopic garners three to five million monthly Spotify listeners while a blockbuster like Bohemian Rhapsody can boost this figure by nearly 20 million listeners.

This phenomenon is not unique to the 21st century. 1984 Best Picture winner Amadeus saw its soundtrack of classical recordings hit No. 56 on the Billboard Top 200 Albums Chart. To reiterate: A music biopic brought 150-year-old music into the zeitgeist.

Musicians—and more importantly, their estates—are well aware of this trend. And thus we have come to the portion of this essay that I will call “bummer town.”

Quite often, a biopic is greenlit by an artist’s estate, either by their children or a firm that has purchased the musician’s back catalog. If the artist’s body of work is a financial stock, then a Hollywood adaptation is a proven way to boost its value.

I once took a meeting with an under-the-radar financial firm that specializes in buying and selling artist discographies. When I asked what they had been working on, they told me they had spent the last three months negotiating the use of an artist’s song in the trailer for a Grand Theft Auto video game. I have no doubt that a music biopic will be made about this musician’s life within the next five to ten years.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: Terms and Conditions

Springsteen ~Colon~ Deliver Me From Nowhere is a strange curio of a movie. The plot centers on the making of Bruce’s acoustic album Nebraska, but the big-ticket music numbers center on “Born to Run,” “Born in the U.S.A.,” and “I’m on Fire.” None of these songs appear on Bruce’s 13th-best-selling album, and were most likely shoehorned into the movie for fan service. And let me tell you, the fans sitting around me were thoroughly serviced by these songs.

The woman beside me clapped along to the beat while the man sitting two rows behind me sang in unison with Jeremy Allen White. I have no idea if these people liked the movie, but they certainly loved the songs.

The experience of watching this film reminded me of the Kidz Bop albums that were wildly popular in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. For those unfamiliar, Kidz Bop took current pop hits and re-recorded these tracks with children’s voices. I assume this concept was commercially successful because they released 51 albums before Spotify killed this business model. For some reason, humans like listening to their favorite songs performed differently, which gave rise to the Kidz Bop Industrial Complex.

Be it Kidz Bop or a music biopic, people cannot resist the childlike impulse to hear the music of their youth played loud with slight stylistic tweaks. There’s nothing wrong with Bohemian Rhapsody and A Complete Unknown pleasing audiences by way of nostalgia—I think it’s quite nice actually. What I don’t like is the corporate engineering that capitalizes on this feeling.

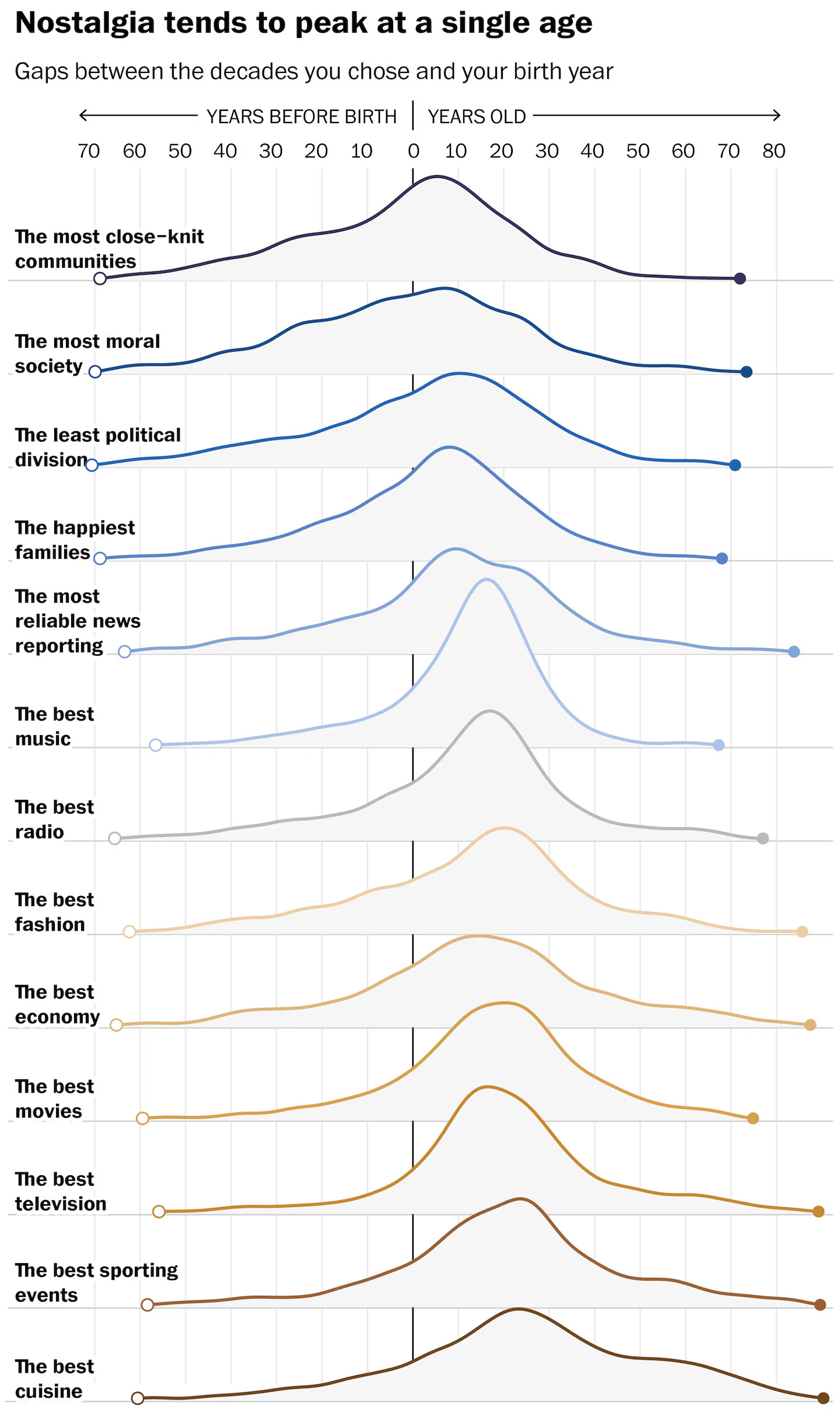

A recent Washington Post article examined the time period for which people feel most nostalgic. Whether it’s music, movies, or politics, most people are wistful for the world they knew during adolescence.

There is a period of cultural vulnerability between the ages of ten and eighteen, when the art and ideas you absorb tend to stay with you for life. If you loved Star Wars when you were ten, then congratulations—you’re a Star Wars fan forever. Suppose you stood in line at midnight to buy the final Harry Potter book: you’ll be visiting Harry Potter World, seeing a Broadway play about Harry’s child, and consuming an upcoming Potter miniseries on HBO Max.

My biggest gripe with fan service and nostalgia exploitation is that a ten-year-old did not sign up for this.

How much smaller would Star Wars’ fanbase be if this bargain came with terms and conditions? You can watch The Empire Strikes Back, and cherish this experience as a formative memory, but only if you agree to watch every Disney+ Star Wars series (in perpetuity).

Which brings me to Springsteen $Colon$ Deliver Me From Nowhere. I was gifted Bruce’s music in my early teens, which means I will pay to hear these tunes performed by Jeremy Allen White, a chorus of Kidz Bop singers, or anyone else with a half-decent voice. This was a bargain I did not know I was opting into, but I guess I’ll enjoy these cultural products nonetheless—and someone will make money off me in the process.

Sure, this entire essay may read like a minor meltdown triggered by a mediocre biopic—but just you wait. Sooner or later, culture will come for you, too. It always does, if given enough time.

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,700 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

I googled "what's up with all these musical biopics lately" and this came up and boy, this was such a good that I subscribed!

Just watch Walk Hard [colon] The Dewey Cox Story. It’s better than all of them put together.