The Rise, Fall, and (Slight) Rise of DVDs: A Statistical Analysis

The death and second life of DVDs.

Intro: The Death of Physical Media

2023 was a disastrous year for physical media and a disorienting one for me personally, marked by a series of ominous milestones:

DVD Sales Declined for the Sixteenth Straight Year: In the first half of 2023, physical media sales in the U.S. decreased to $754 million, down from $1.05 billion during the same period in 2022.

Netflix Ended its DVD Rental Service: On September 29, 2023, Netflix mailed its final disc, marking the end of its DVD rental service.

Best Buy Discontinued DVD Sales: In October 2023, Best Buy announced that it would stop selling DVDs and Blu-rays.

I Decided to Start Collecting DVDs: In November of 2023, I informed my wife that I wanted to begin collecting DVDs, to which she responded, “Why?”

There was once a time when people would buy the right to watch a film twice, once in theaters and then on DVD. Consumers could own their favorite films, and studios made tons of money serving this demand. But over the last 20 years, physical media has declined to near-extinction as streaming has evolved into the predominant mode of home entertainment.

And yet, in recent years, DVDs have seen a modest revival—not as a durable consumer good, but as a form of self-expression. If that sounds hokey or illogical, it’s because it is. People (myself included) are trading convenience and economic efficiency for emotional gratification. And, so far, I’m loving it.

So today, we’ll explore the rise and fall of physical media, the changing economics of movie ownership, and the minor resurgence of a dying technology.

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by The Stat Significant Dataset Hub

Access 200+ Curated Datasets to Elevate Your Analysis

Want the data behind the deep dives? The Stat Significant Data Hub gives you access to 200+ curated datasets spanning movies, music, TV, economics, sports, and more.

New datasets are added weekly, with full archive access for Stat Significant paid subscribers. Since last week’s post, we added 10 new datasets—covering everything from the most commonly searched guitar chords to Formula 1 to chess games.

The Rise and Fall of Physical Media

Fifty years ago, you couldn’t watch movies at home (apart from whatever played on cable television). Let’s say you actively wanted to see Citizen Kane or take in Alfred Hitchcock’s entire filmography; well, you couldn’t. You’d accept the ephemeral nature of movie consumption and think, “I guess I may never see my favorite film again. What a bummer.”

The arrival of VHS in the late 1970s marked the birth of the home entertainment industry, giving consumers unprecedented control over what they watched.

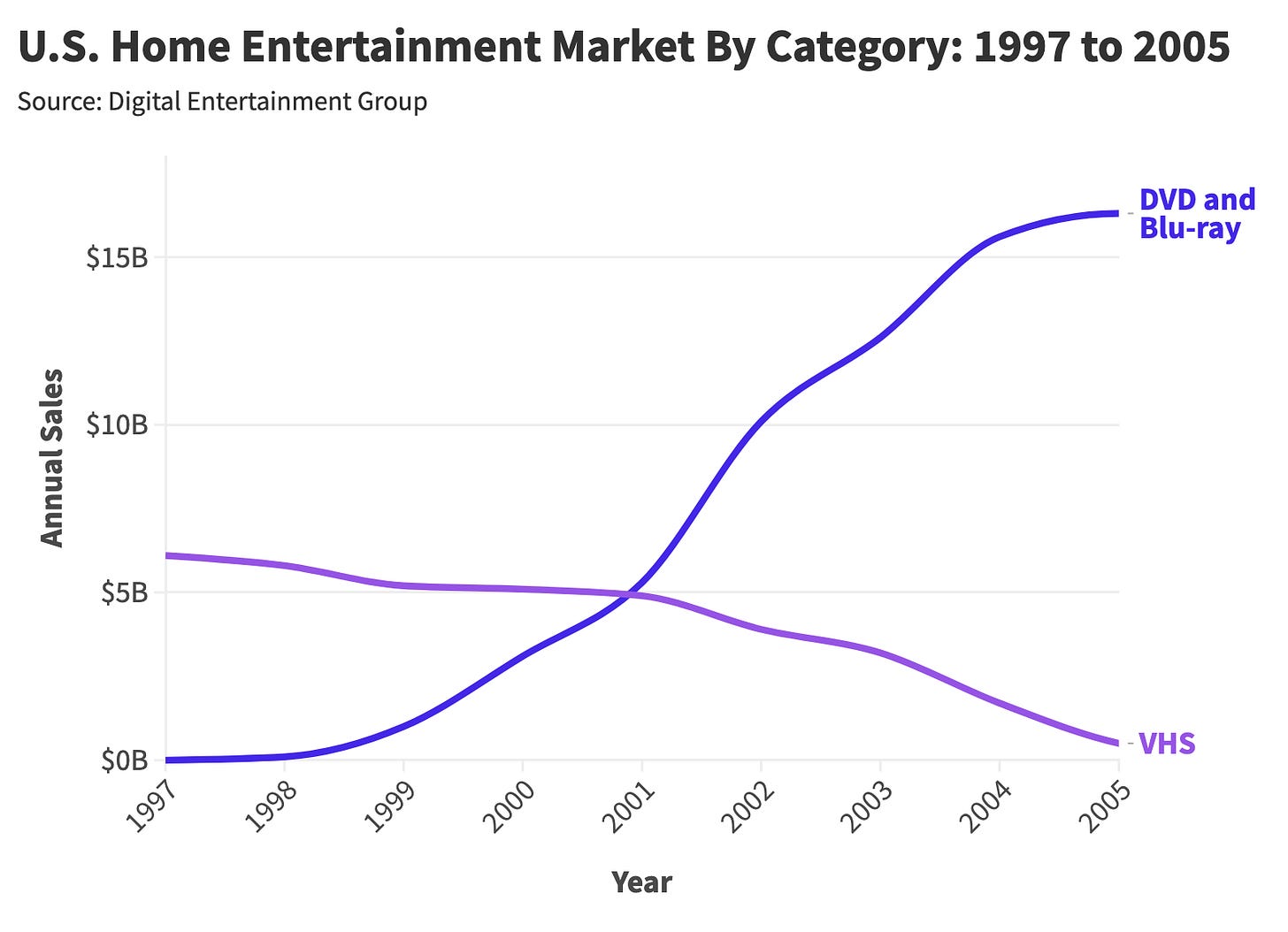

The late 1990s brought DVDs, which offered higher video quality and interactive features. Discs swiftly overtook videotape as the go-to format for home entertainment, with annual DVD sales peaking at $16 billion in 2005.

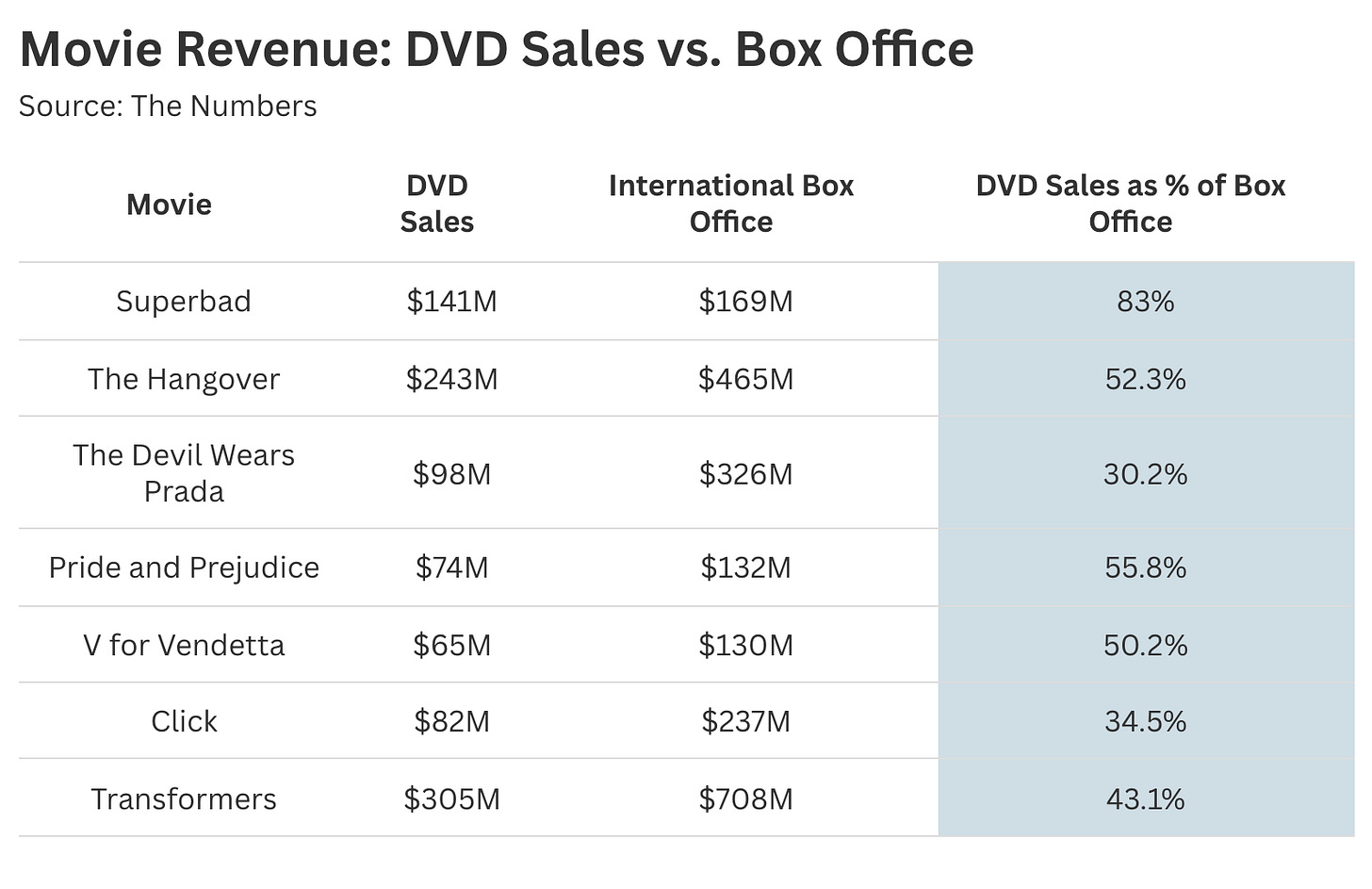

This dependable revenue stream allowed studios to take bigger risks. If a film underperformed in theaters, strong DVD sales allowed those projects to turn a profit.

Based on a handful of case studies from the early 2000s, it appears DVDs generated revenue equivalent to roughly 50% of a film’s international box office.

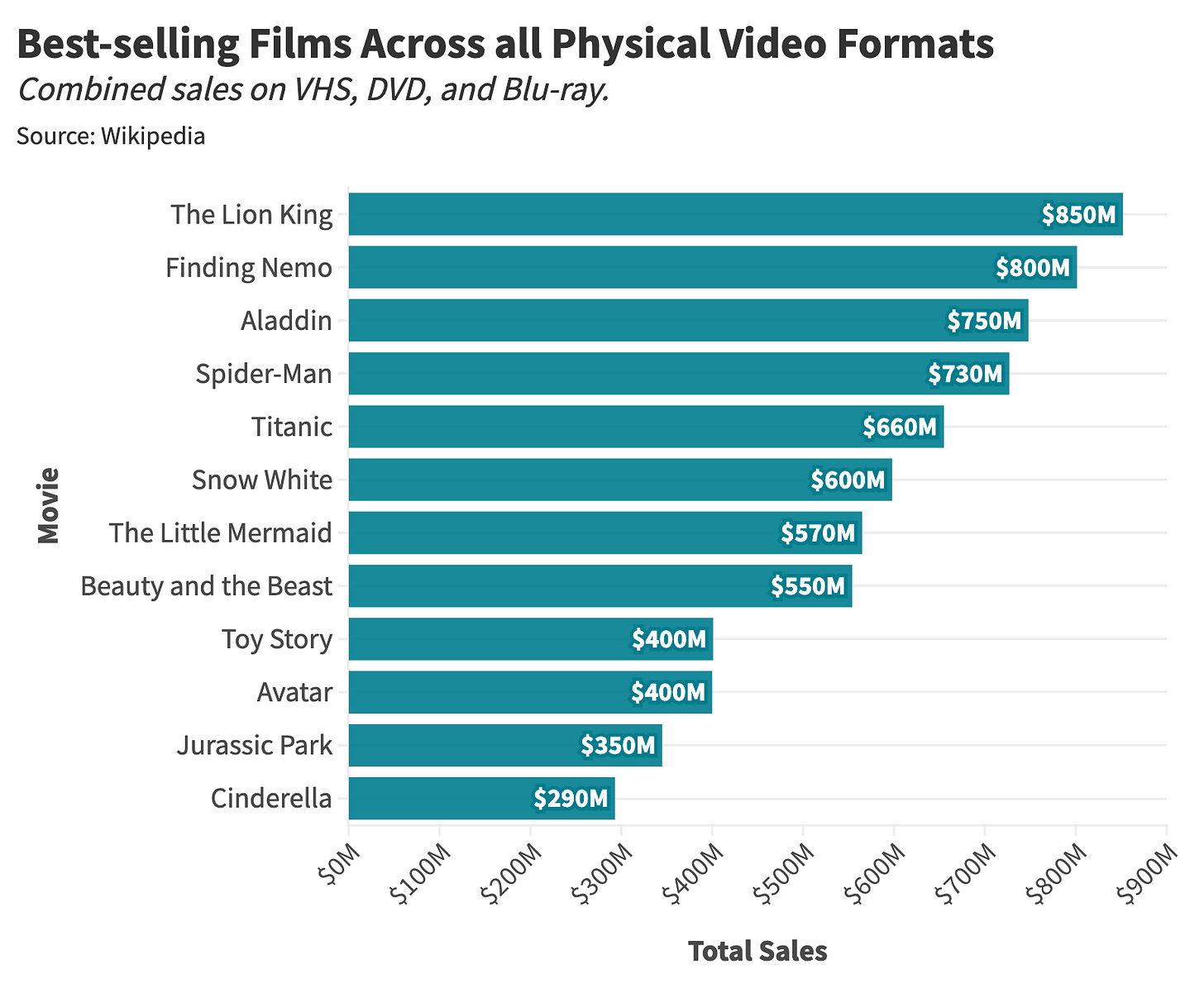

Physical media was a cash cow for movie studios, who could sell a single film to the same consumer multiple times. Let’s say you loved The Lion King in a world before streaming: you might be paying Disney for a movie ticket, a VHS tape, a DVD, a Blu-ray, and now a 4K disc. That’s at least $100 of Lion King spending.

Many films enjoyed active second lives on DVD and VHS, with hit titles grossing over $500M in additional revenue for Hollywood studios.

If these numbers seem too good to be true, it’s because they were.

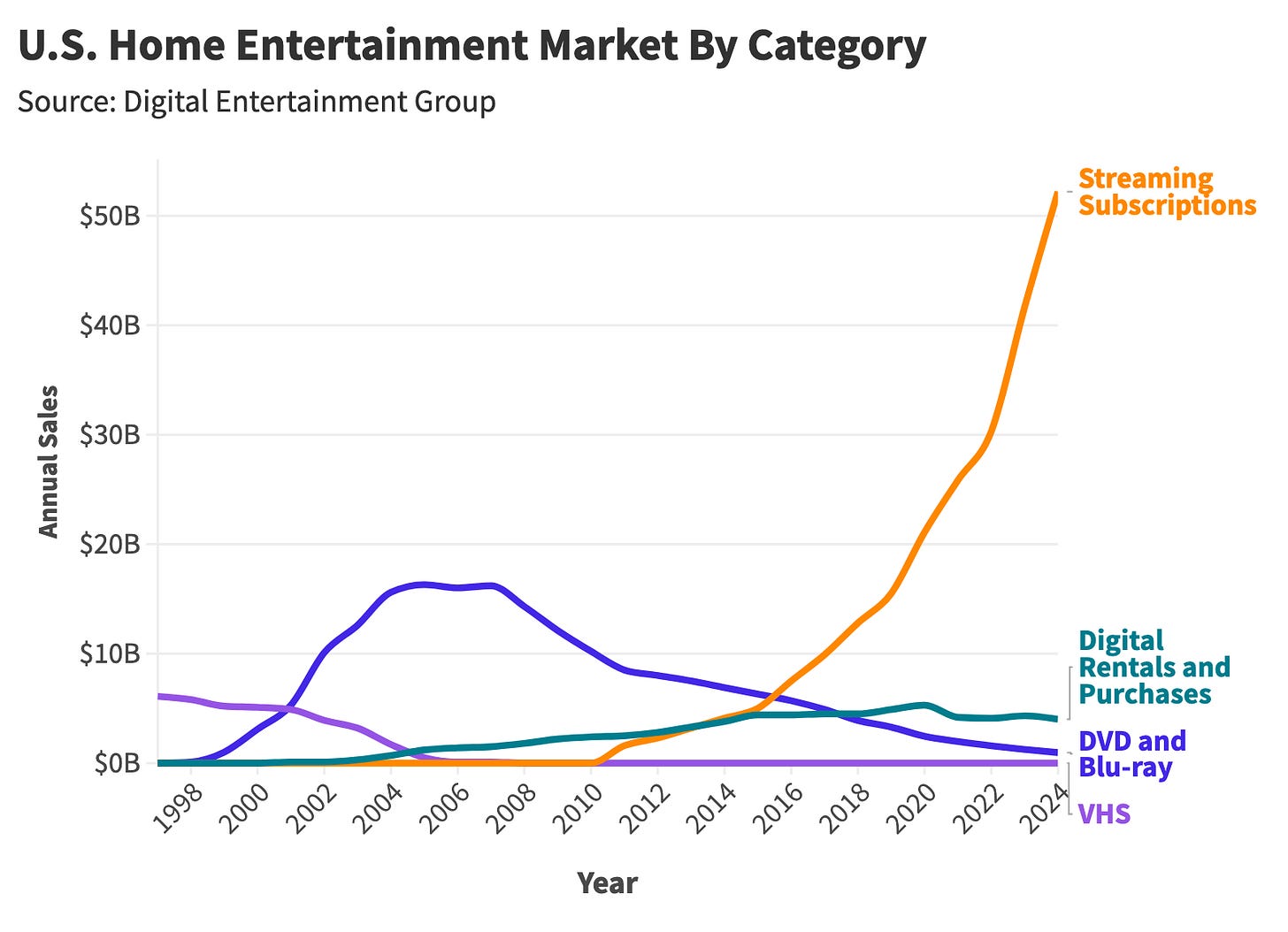

In January of 2007, Netflix launched its streaming service, providing consumers with an expansive selection of film and TV programming with virtually no friction. Movie watching was no longer bound by physical constraints, and a treasure trove of content was yours for a measly $5 a month. DVD sales plummeted as streaming subscriptions, digital rentals, and digital purchases grew to a combined ~$60B in annual sales.

Consumers didn’t have to settle for video rental stores or cable reruns of Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives; consumers could watch something remarkable whenever they pleased. Thus began the era of Peak TV, as numerous streaming platforms entered the market while content production and consumption increased exponentially.

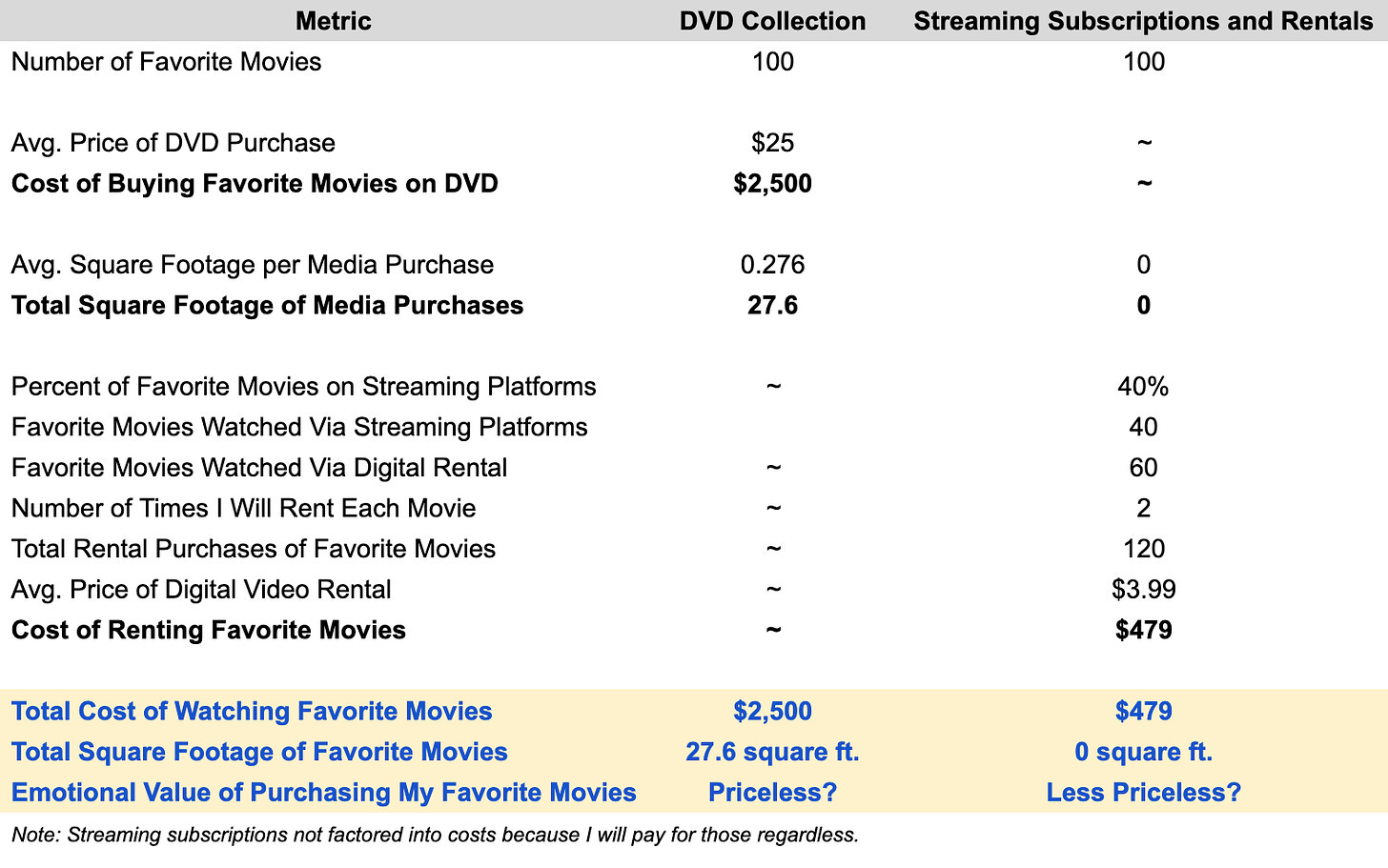

Suddenly, the idea of owning your favorite film became impractical. Let’s say I want to buy every movie from my Letterboxd list of 100 all-time favorites: I can buy these titles in physical format, or I can rent and stream them whenever I want. Assuming I watch each of these films two more times before I die, it will cost me significantly more to build a DVD collection while also taking up a non-trivial amount of space in my apartment. See the calculations below:

To collect DVDs is to embark upon a path of financial inconvenience. The economic reality is that streaming is cheaper, provides greater selection, and offers minimal friction. It is the superior format for most consumers.

The discontinuation of Best Buy and Netflix’s DVD programs was broadly seen as a death knell for physical media. Slate lamented, “The Death of Netflix DVD Marks the Loss of Something Even Bigger,” and The Hollywood Reporter wrote a eulogy for the era of physical media. And just like that, DVDs were an anachronism, a tool rendered extinct by technological progress, much like 8-tracks, BlackBerrys, floppy disks, Quibi, and pagers.

And yet, physical media lives. While retail demand for movie collecting has diminished, DVDs still prosper in a niche secondary market, much like stamps, coins, and baseball cards.

The Second Life of DVDs

The past six years have been rough for cinephiles. Moviegoing collapsed during the pandemic and has been slow to recover. Stories previously produced for the big screen are more likely to be adapted into limited series. Streaming content is unlimited, yet these cultural products have no tangible form. In short, it’s been a weird time for da’ movies.

In response, cinephiles have retreated online and turned backward. Platforms like Letterboxd—a social network for cinema obsessives—offer film lovers a digital community for logging, debating, and cataloging movies, serving as an at-home substitute for the social ritual of moviegoing. At the same time, many film nerds have quietly rejected the ubiquity and amorphousness of streaming in favor of the tangibility of DVD collecting.

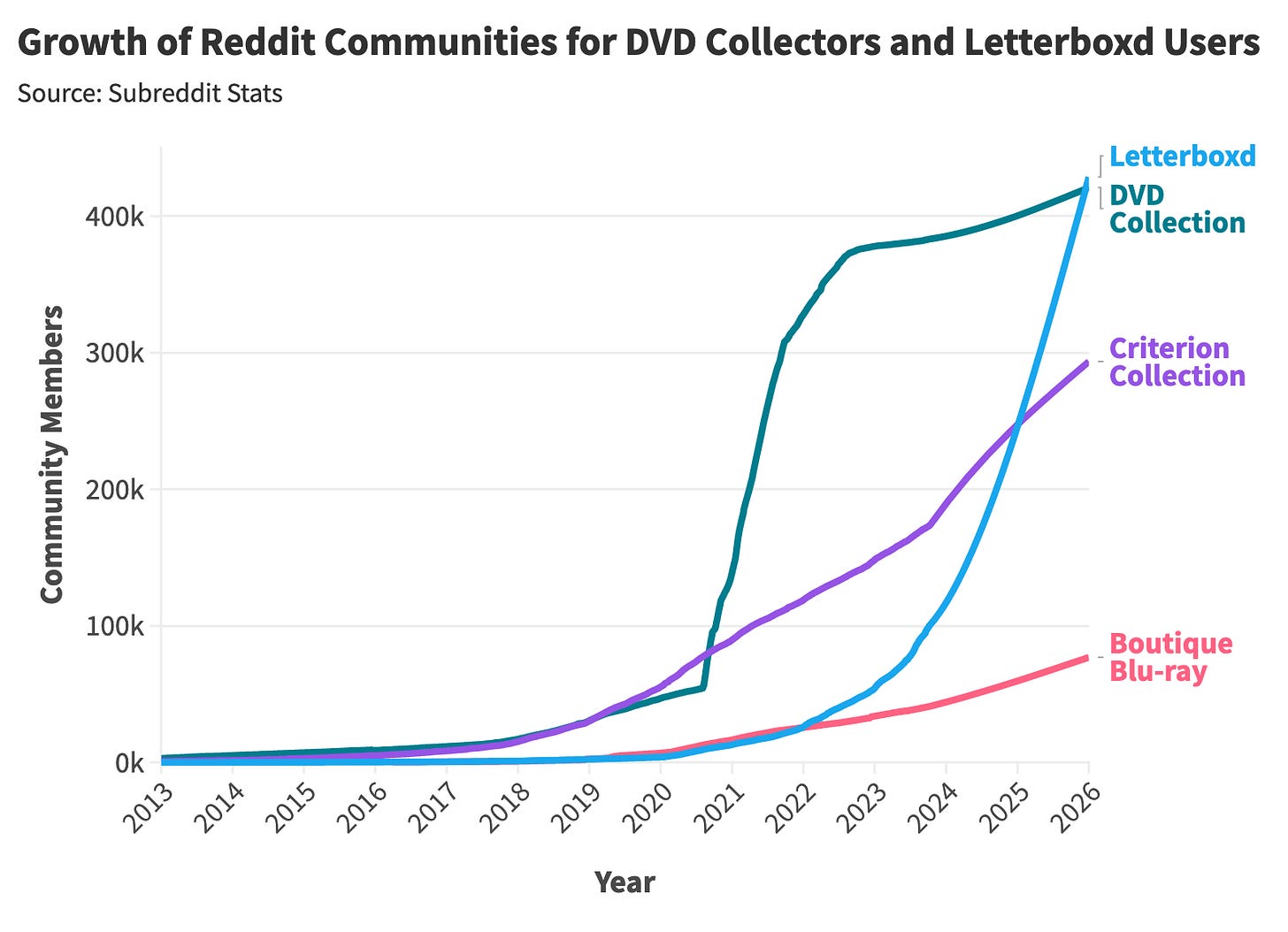

In recent years, online communities centered on physical media have experienced substantial membership growth, with Reddit groups dedicated to DVD ownership gaining hundreds of thousands of new members.

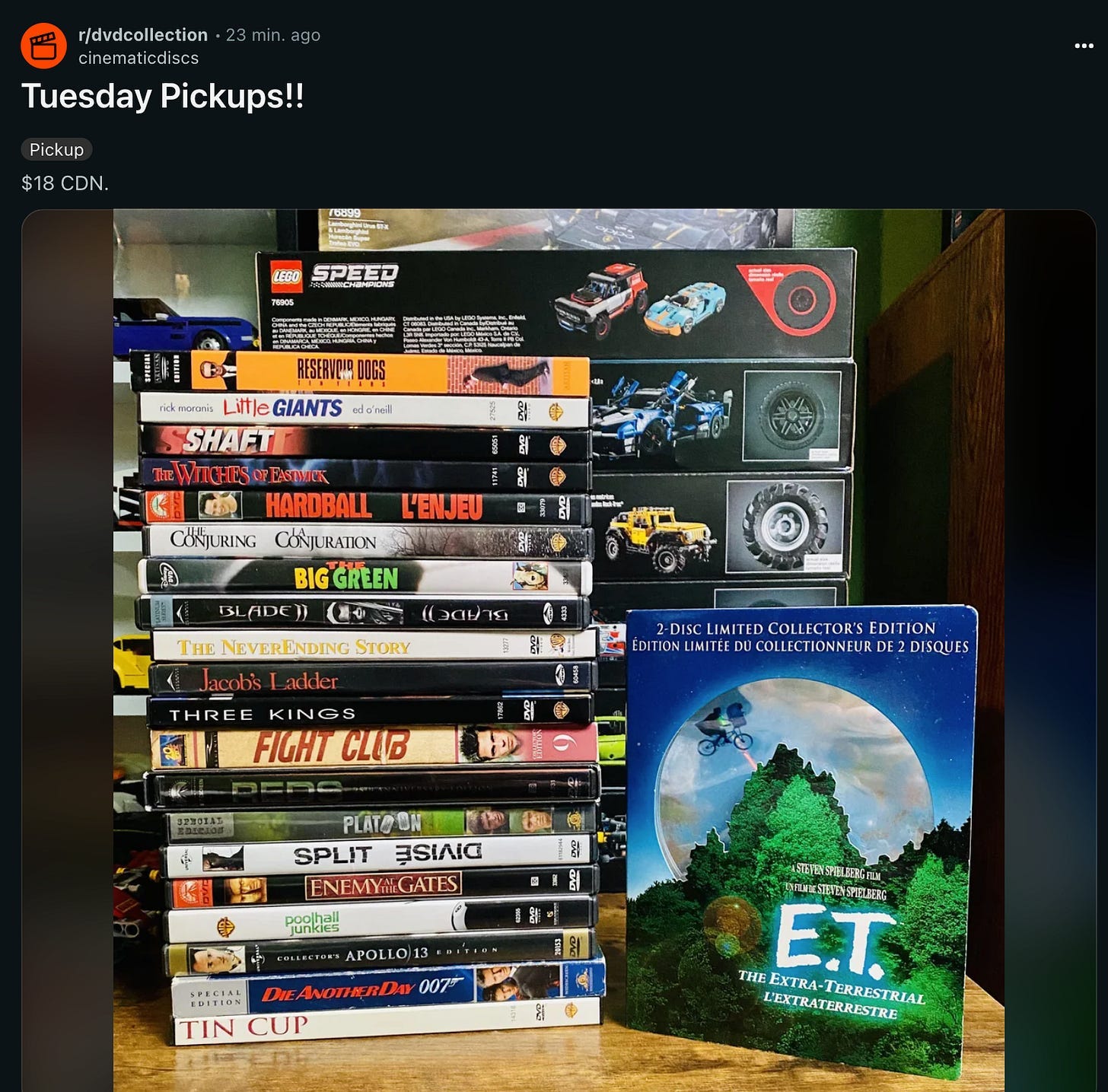

These communities allow hobbyists to connect through their passion, offering tips on finding rare titles and a forum for showcasing their collections.

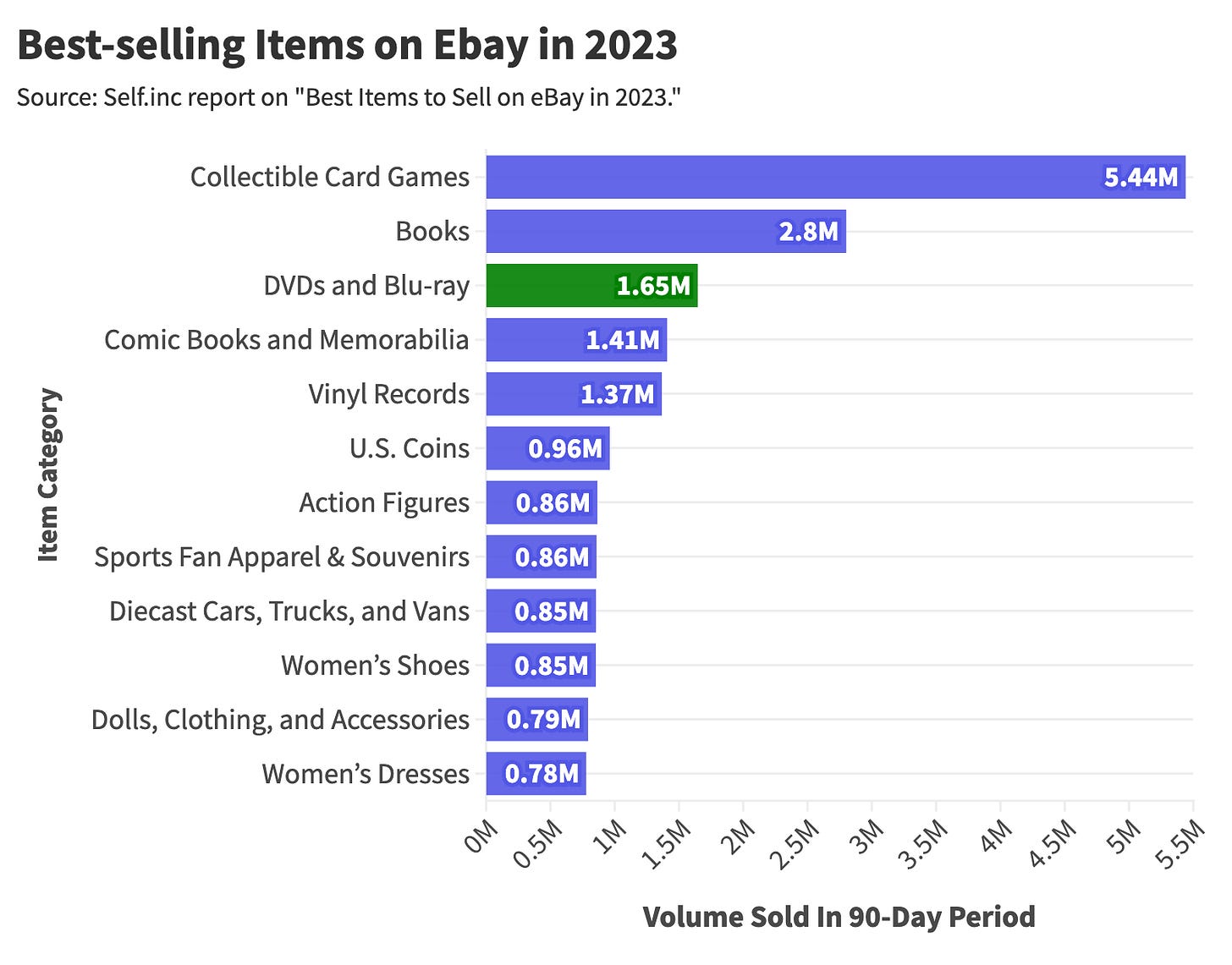

The collapse of DVD sales channels has turned physical media into a collector’s pursuit. eBay, the world’s largest platform for trading memorabilia, has benefited significantly from retail’s abandonment of physical media. An industry report from Self on “The Best Items to Sell on eBay in 2023” found DVD and Blu-ray to be the third-highest-selling category on the site.

eBay’s DVD listings constitute a bizarre market bifurcated into two distinctive product offerings. On one end are sellers indiscriminately unloading boxfuls of Blu-rays for less than $2 a disc.

On the other end of the spectrum is an upscale market for collectors interested in high-quality packaging (slipcovers, beautiful artwork, steel casing, etc.) for 4K-mastered movies, like this copy of The Social Network, which I really want to buy.

Unfortunately, this collectible is priced at $73(!!!), which is equivalent to ~5.5 Chipotle burritos, and is, therefore, too much to spend on a dying media format. Or is it?

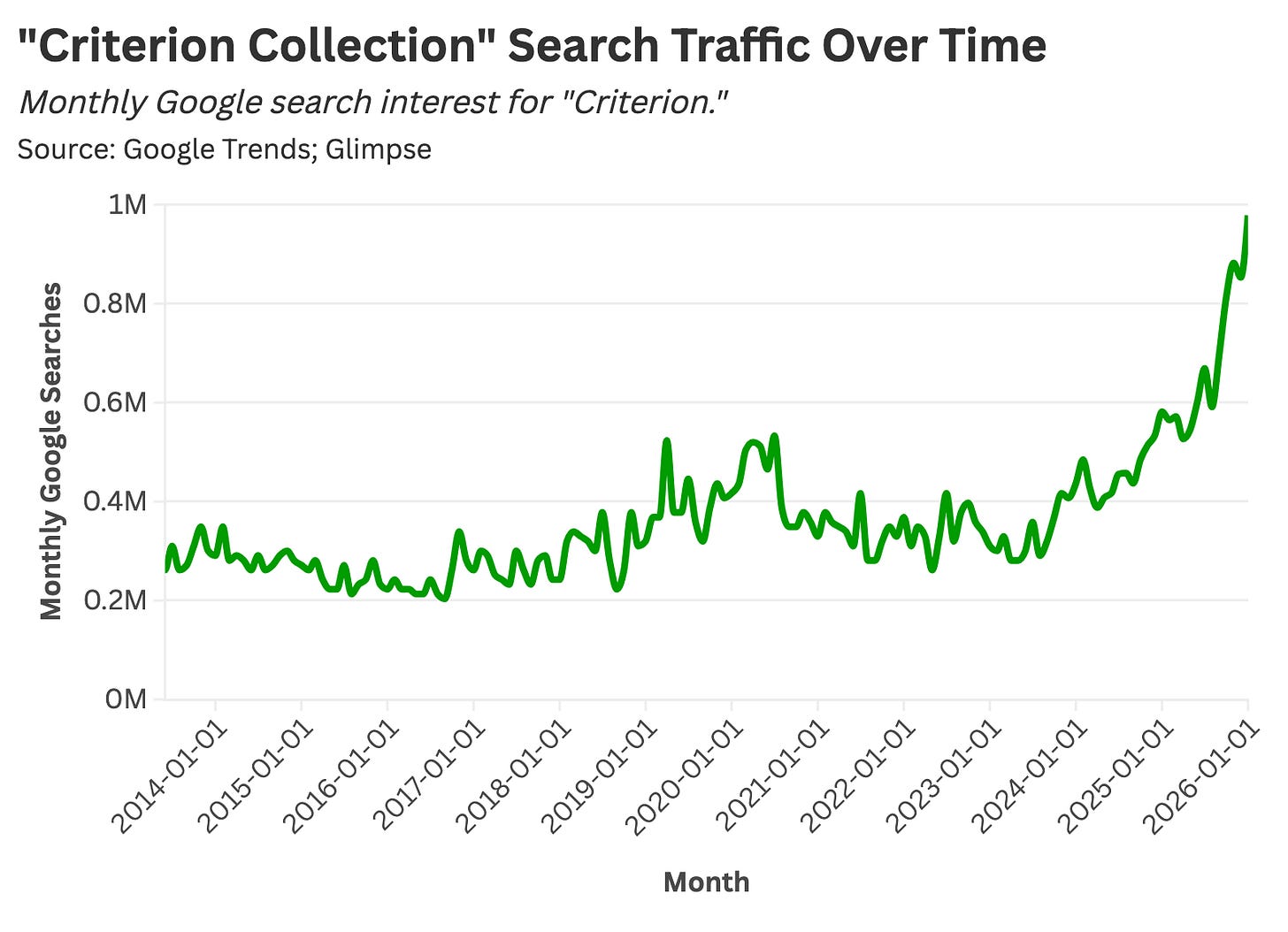

Boutique labels like Vingar Syndrome, Shout Factory, and the Criterion Collection have seen considerable growth in recent years, offering premium collectibles for enthusiasts. Criterion, in particular, has emerged as the de facto leader in this highly specific space, and has seen search traffic nearly triple over the past year.

Recently, the label released a 4K version of the 1976 film Network, one of my all-time favorite movies, thus giving me the opportunity to repurchase a film I already own. Only a very small percentage of readers will find this transaction “cool” or “defensible.”

Herein lies the perpetual dilemma of this absurd hobby. On the one hand, I want to own this aesthetically pleasing physical representation of a beloved film. On the other hand, I could rent this film 18 times if I didn’t buy the DVD. Should I indulge myself or be a rational actor? And why am I doing this in the first place?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: The Irrational High of Collecting

The other week, I stumbled on a $2.99 Blu-ray copy of Inception at a record store. “What a steal!” I thought to myself. Upon completing my purchase, I hustled out of the shop, fearing the cashier might notice the pricing error.

Standing outside the record store, prize in hand, I couldn’t help but rejoice. “What idiot would price this so low?” I thought. And then, standing there, holding a relic of a dying technology, I realized that I might have been the idiot. $2.99 was a fair price for something most people consider junk. It was at this point that I got a bit sad.

But then I took the movie home, and I watched it. There was something wonderful about watching a film that I owned. I love knowing the movie is physically in my apartment, and I enjoy looking at my DVD collection—marveling at the cases, like Gollum from The Lord of the Rings.

That said, I am deeply conflicted about this newfound hobby. I quantify things for a living, and this collector’s pursuit is quantifiably foolish.

I do not believe:

That my favorite movies will disappear from streaming services.

That I am single-handedly preserving film history, as Guillermo Del Toro has suggested.

That streaming is terrible and will eventually fade away.

That other people should do this.

I have one reason for collecting physical media:

Movies have been a big part of my life, and I want to own the things I love in material form.

At times, I feel like an eight-year-old collecting Pokémon cards, questing for a holographic Charizard. Forming an emotional attachment to a piece of cardboard or a DVD case is bizarre, but is it wrong? I don’t really know. Perhaps it’s best to suspend my cynicism, stop quantifying everything ad nauseam, and simply enjoy the thrill of caring about something.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

*Note: For best results, open this link in a web browser while logged in to your Substack account.

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

The reasons I buy physical:

* Video quality is better. If I am going to spend 2 hours if my life watching a "good" movie, I don't want to see a bunch of distracting streaming artifacts.

* Extra features, commentary by the director or a film historian

* The pile of unwatched discs acts as a physical "watch list"

There are a ton of films from the 1960s and before which are not found on streaming services. The streaming services are looking to make money, and they feature films which draw viewers. The movies are meant to be easily recognized and get people to join. There are many great films which are not well known.