The Rise and Fall of Music Ringtones: A Statistical Analysis

What happened to the music ringtone?

Intro: The Ballad of Crazy Frog

Sometimes, human creativity gives us The Godfather, Beethoven's 5th Symphony, and The Wire—and sometimes that same ingenuity gives us Crazy Frog.

When it comes to Crazy Frog, people generally fall into three camps:

Those who vividly remember this meme-turned-ringtone-turned-song and would like to forget.

Those who've forgotten whether Crazy Frog is the name of a song or artist or noise, subsequently stream this track, remember it, and are regretful.

Those born after 2000 who have never heard the words "Crazy" and "Frog" used together.

Crazy Frog originated as an audio meme called "The Annoying Thing," recorded by a Swedish teenager in the late 1990s (which reads like an AI hallucination but is, indeed, fact). In 2003, a Swedish animator created a 3D frog character to accompany "The Annoying Thing," which caught the attention of ringtone maker Jamba!, who eventually combined "The Annoying Thing," the 3D frog character, and the theme music from Beverly Hills Cop, rebranding this conceptual Frankenstein as "Axel F."

At its peak, Crazy Frog captured 31% of the UK ringtone market, generating over £40 million in sales in 2005, driven by an extensive advertising blitz where the song was featured up to 26 times a day on British television (per channel), reaching an estimated 87% of the population. The ringtone was so ubiquitous that it later spawned a full-length single, which climbed to #50 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Crazy Frog's meteoric rise is a perfect encapsulation of the 2000s ringtone craze: a grating 30-second meme that started as a phone alert, morphed into a charting single, and is now a forgotten relic—practically unknown to Gen Z.

For five years, record labels raked in billions of dollars selling polyphonic ringtones, mostly to fans who already owned these songs on a combination of vinyl, CD, and iTunes. However, this gold rush was fleeting, gone months after its peak.

So today, we'll trace the rise and fall of music ringtones, examine what led to their rapid decline, and spotlight a corner of the world where this anachronistic phenomenon still thrives.

The Rise and Fall of Music Ringtones

In the early 2000s, polyphonic ringtones solved a major problem for the music industry and a trivial pain point for consumers. For everyday people, customizable ringtones became an answer to a question no one had really asked: "How do I broadcast my personality every time my phone rings?" For record labels, they offered a (temporary) solution to a much weightier dilemma: "How do we make money in a post-Napster music landscape?"

In 1996, Finnish carrier Radiolinja introduced downloadable monophonic ringtones, allowing users to buy one-note renditions of popular songs. In 2001, Japan's TrueTone introduced real-music ringtones made from actual song snippets. A year later, U.S. carriers like AT&T launched official ringtone storefronts, sparking a boom in American ringtone sales.

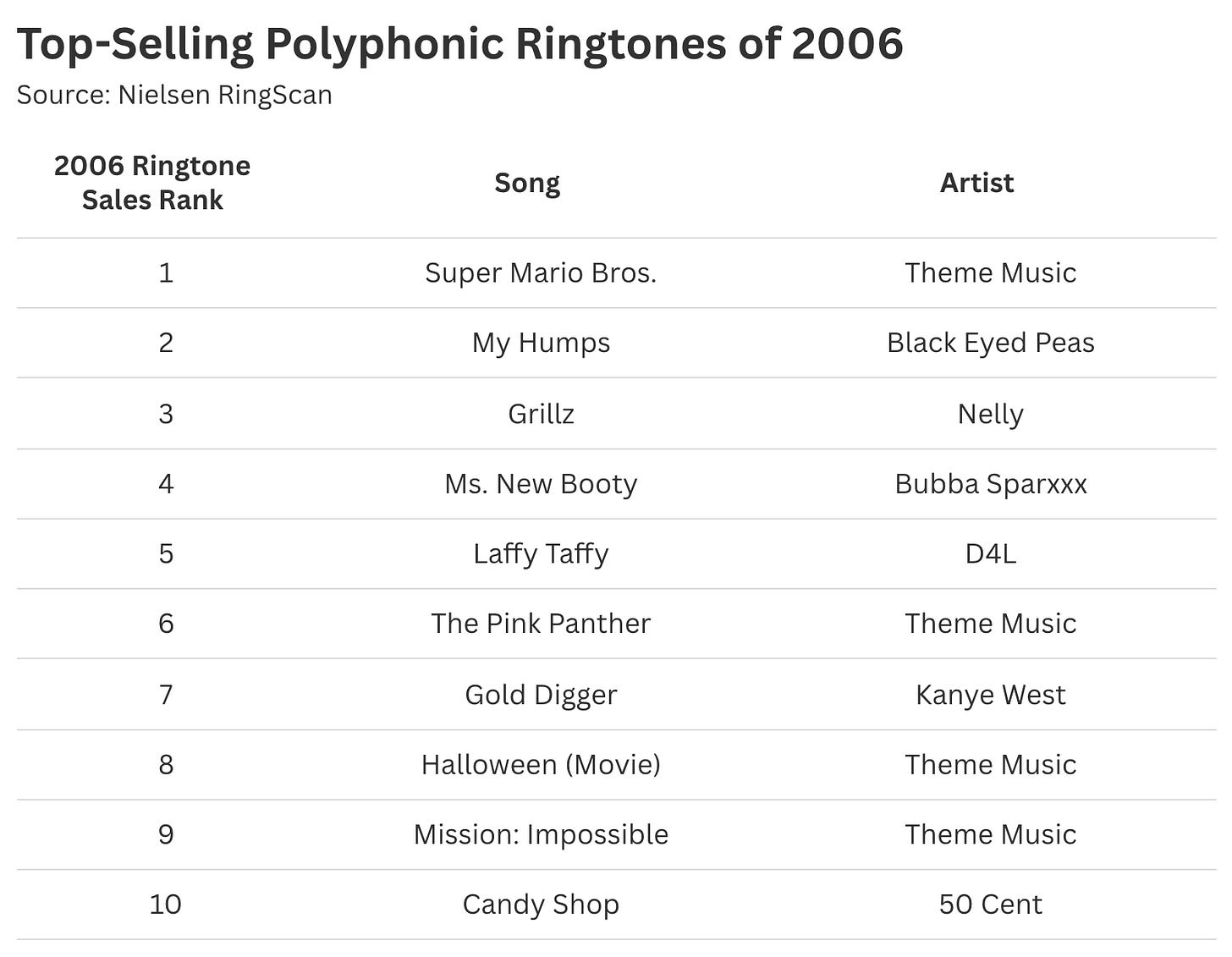

In 2004, the analytics firm Nielsen began tracking ringtone purchases, and a year later, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) began publishing ringtone sales data as part of its coverage of industry revenues. While track-specific data is scarce, Nielsen did release annual rundowns of each year's best-selling songs. 2006's list of top-sellers features a mix of contemporaneous hits like "Candy Shop" and "Ms. New Booty" alongside evergreen theme music for Super Mario and Mission: Impossible.

My personal favorite from this group is the theme music from Halloween. Nothing says "this is who I am" like referencing a film where a masked sociopath stalks and murders suburban teenagers.

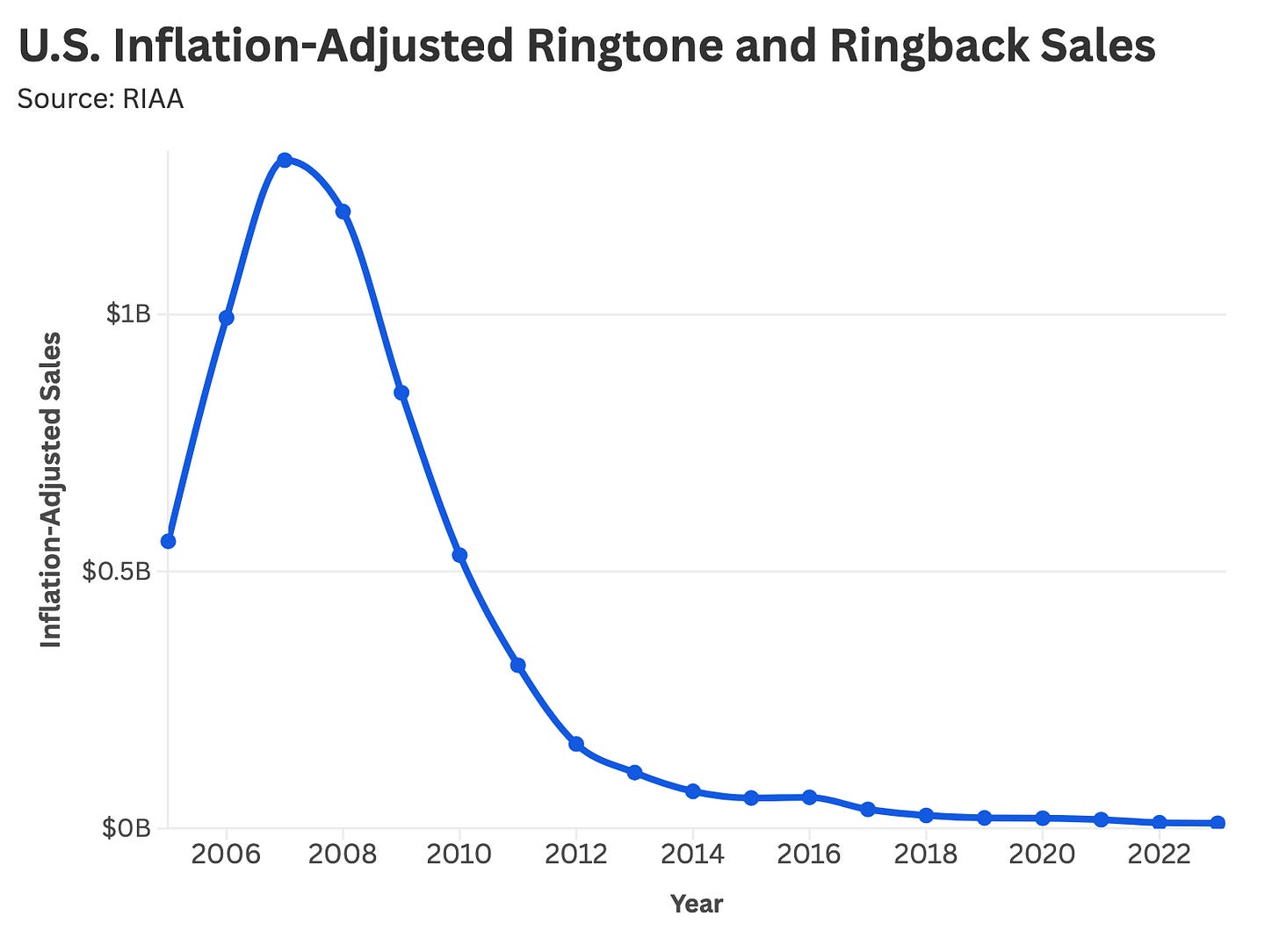

In 2006, annual U.S. ringtone sales increased by nearly $400 million, then rose another $400 million the following year, eventually peaking in 2007. This period saw industry pundits forecasting a $10 billion ringtone market that would single-handedly save the music industry. In hindsight, these reports are quaint: by 2008, sales were already in decline, and by 2014, the U.S. market had all but disappeared.

In the music industry, financial collapse usually stems from the arrival of a new medium. Cassettes gave way to CDs, which were undercut by Napster, which was supplanted by iTunes, before Spotify and streaming came to dominate the market. Ringtones, however, weren't killed off by some newfangled successor; they simply fell out of fashion. The inevitable question is why: how did annual demand for this product plunge from $1.2 billion to $100 million in just five years, without any clear competitor taking its place?

The answer can be found in ever-evolving cell phone etiquette and the unlikely durability of ringtones in South Asia.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Why Did Music Ringtones Fall Out of Fashion?

Declining ringtone sales can be traced to a combination of shifting technological trends and amorphous cultural forces.

I'll start with the mushiest explanation: music ringtones were a novelty that solved no tangible problem, and after a handful of purchases, people grew tired of hearing 30-second snippets of "Candy Shop" and "Ms. New Booty" on repeat. Buying a ringtone was fun; living with that ringtone for several months was significantly less fun. I have no data to support this hypothesis other than the total absence of this phenomenon from everyday life. If people wanted real-music ringtones, then we'd still be buying them. This logic is either circular nonsense or deeply profound—perhaps a bit of both.

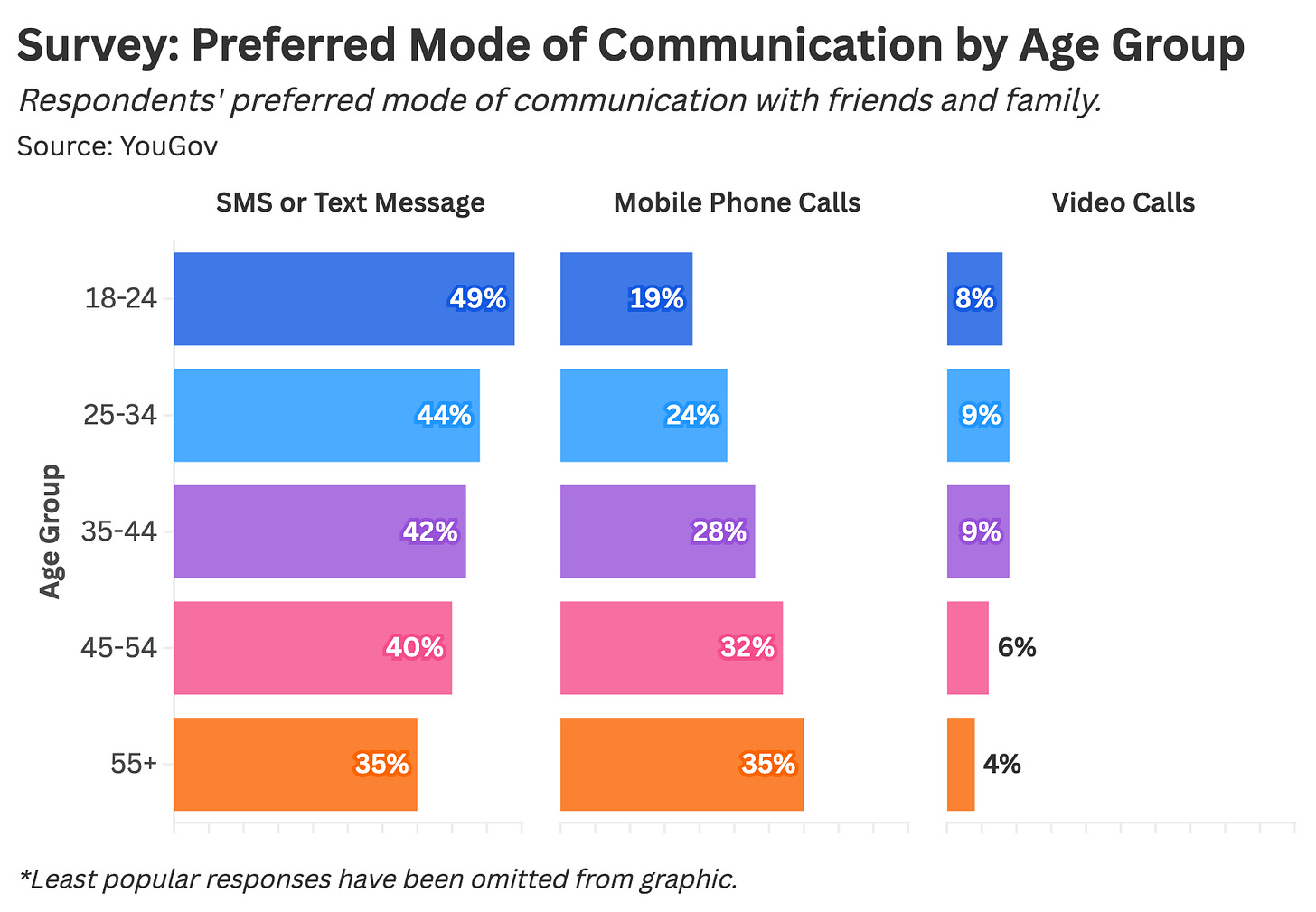

A more tangible explanation for the ringtone's demise is the waning relevance of the phone call itself. Roughly 50% of modern cell owners set their devices to silent or vibrate, a habit fueled by a growing aversion to phone conversation. A 2023 YouGov survey found that texting is steadily replacing calls as a preferred mode of communication.

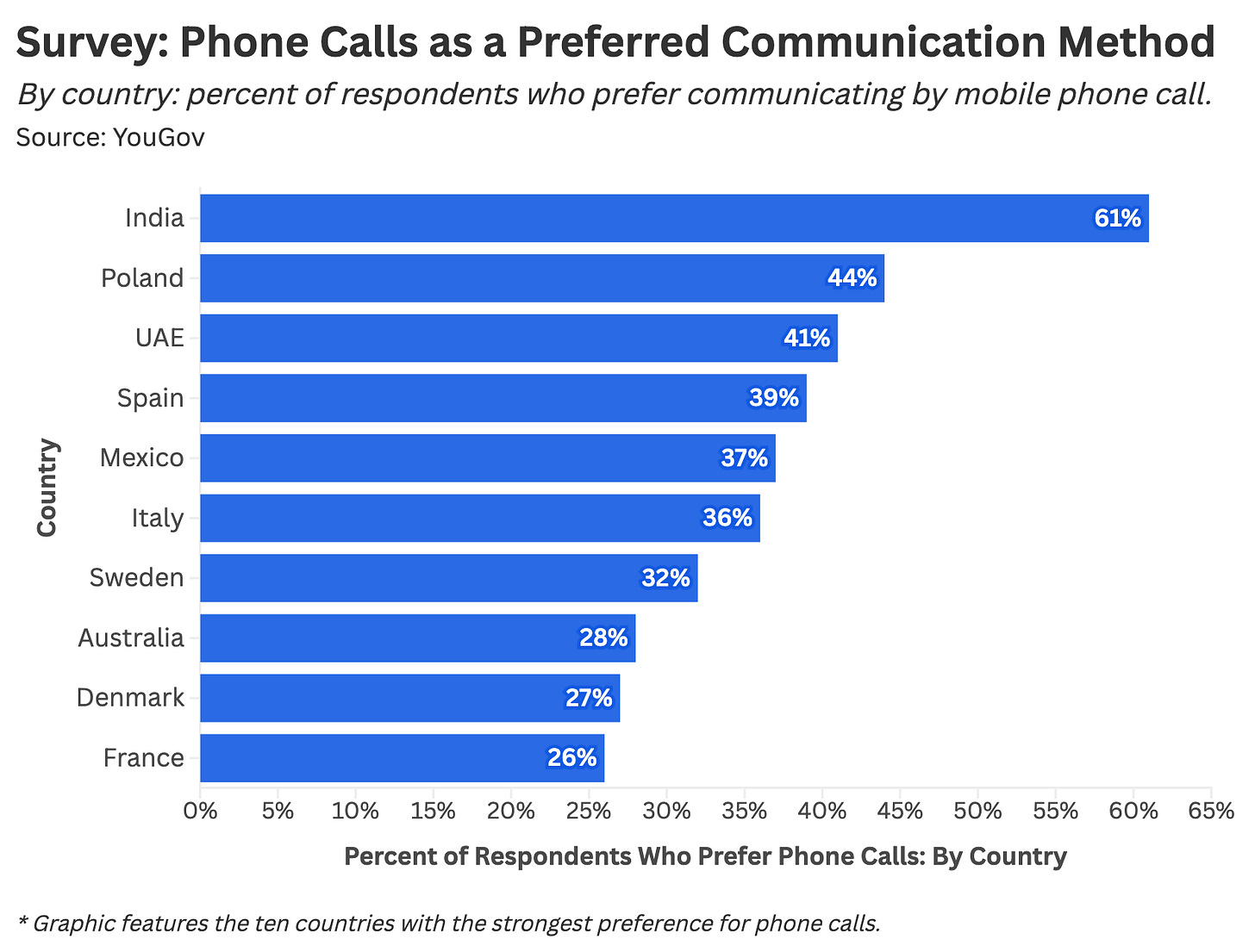

Yet the phone call's creeping obsolescence is not universal. According to this same YouGov poll, India retains a strong preference for phone conversation, making it a notable outlier among all nations surveyed.

I couldn't find a sufficient explanation for India's commitment to phone calls. The limited research I found points to an appreciation for tonal nuance and efficiency, but these values are extremely vague and thus difficult to attribute to an entire nation. Whatever the rationale, India's telecommunication habits make the country a distinct outlier in ringtone consumption.

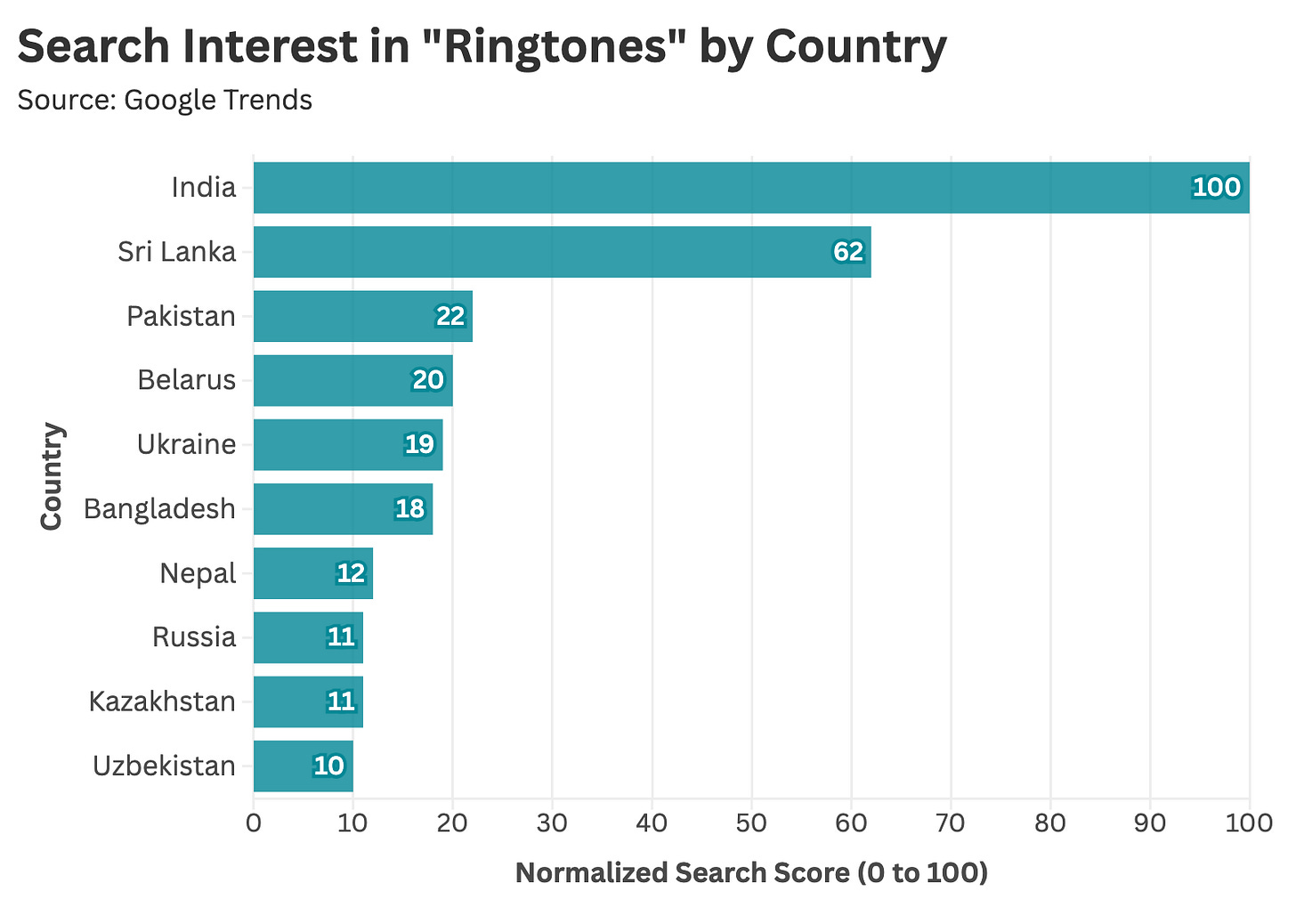

According to research from friend of the newsletter Chris Dalla Riva, nearly 93% of Google searches for "ringtone download" come from India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, with India being the overwhelming leader in "ringtone"-related queries.

In a culture that values phone calls, the ringtone endures as a form of self-expression, tied to a ritual that smartphones and social media have rapidly reshaped. If ringtones do address a consumer pain point, it's one that vanishes when a phone is set to vibrate or when a text message replaces a call.

Final Thoughts: Who Asked for This?

Whenever I tell people about this article topic, they respond with performative nostalgia. Upon hearing the words "music ringtone," listeners will tilt their heads back, gaze into the middle distance, and emit a wistful sigh, "Ah, music ringtones—I miss those..."

This is false nostalgia, proof of our ability to romanticize just about anything (like when a person claims to be nostalgic for the first two weeks of the pandemic). People do not miss music ringtones; they miss being young(er), which is a time when music ringtones happened to be ubiquitous. And if you truly miss polyphonic ringers, you'll have to respectfully disagree with the next five paragraphs.

For one, the introduction of real-music ringtones unleashed a widespread Pavlovian experiment, conditioning purchasers to despise their favorite songs. When I was in middle school, I paid $12 for "By the Way" by The Red Hot Chili Peppers to be my ringtone. At first, this was awesome because I love this song, but it soon became a Faustian curse. Now, I kind of hate this song, with an overwhelming aversion to the 30-second snippet that served as my ringer. As I get older, I am increasingly sick of my own music (I can only listen to Blink-182 so many times), and somehow, music ringtones condensed this process into a matter of weeks.

Yet my greatest frustration with the real-music ringtone is that nothing new was created. When cassettes were introduced, one could argue that they offered greater portability. CDs allowed music to be packaged in a convenient form factor along with more storage space. iTunes enabled consumers to carry hundreds of tracks in their pocket, and streaming offers low-cost access to all recorded songs. Music ringtones, however, are just poorly rendered versions of tracks that someone may have already purchased five times.

This conceptual redundancy earns polyphonic ringers the most ignominious of cultural honors, belonging to a group of products that beg the question, "Who asked for this?" This list of unneeded consumables includes Madame Web, a TV show about Velma from Scooby-Doo, every Disney live-action remake, a Netflix game show that replicates Squid Game but not ironically, every Disney legacy-sequel, Pedro Pascal starring in every movie released in 2025, every Disney+ series that besmirches Star Wars's legacy (with the exception of Andor), Imagine Dragons, a TV series where Mr. Beast replicates Squid Game but not ironically, and most movies that star Chris Pratt.

In these cases, "who asked for this?" is rhetorical, posed when the assumed answer is "nobody." These products are ostensibly bred from pure cynicism, where their lack of newness becomes a selling point. It's all reheated leftovers. The people who "asked for this" are almost always the ones making and selling that thing.

Aside from a few hundred million people in South Asia, no one is clamoring for a personalized jingle that announces their every phone call—or to receive a phone call at all. And if you somehow feel nostalgic for the 2000s ringtone boom, remember that this medium's commercial zenith was a frog-centric Frankenstein born from a Swedish teenager making an irritating noise, which may be the textbook definition of a cultural product nobody asked for.

Got a Data Challenge? Stat Significant Can Help!

Struggling to turn your data into actionable insights? Need expert help with a data or research project? Well, Stat Significant can help.

We help businesses with:

🔍 Insights That Improve Performance: Turn raw data into strategic intelligence that guides smarter decisions.

📊 Dashboards That Drive Action: Transform your data into clear, interactive dashboards, giving you real-time insights.

⚙️ Data Architecture That Automates Reporting: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

At one time you could assign ringtones to your contacts so you could tell who was calling without looking. When Android made this feature unavailable I stopped buying ringtones. Just my personal experience

Plus... people have been able for many years to create their own ringtones from digital files (or imported CDs) that they already own. Why would anyone pay $1.29 when they could spend less than a minute making their own ringtone?