The Broken Economics of Streaming Services: A Stats Explainer

Why streamers are struggling, and how things may get worse.

Intro: The Collapse of Paramount

In the 1970s, Paramount produced a remarkable slate of movie classics, including The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Chinatown, Grease, Saturday Night Fever, Apocalypse Now, and several other works considered cornerstones of the great American film canon. This period of movie history would become the stuff of Hollywood legend, with Robert Evans, Paramount’s most visible executive, later releasing a tell-all book about his stewardship over the studio’s unprecedented run in the 1960s and 1970s. To this day, Evan's memoir “The Kid Stays in the Picture” remains one of the best-selling movie books of all time, a testament to the enduring significance of Paramount’s golden decade.

Fast forward to 2021, and Paramount, now an ailing media conglomerate, decides to launch Paramount Plus, becoming one of the last Hollywood studios to enter the streaming business. Amidst declines in cable subscribership and moviegoing, Paramount Plus is the studio's last-gasp attempt to refashion itself as a new-fangled tech company, à la Netflix.

Now, fast-forward to 2024, and Paramount's credit rating has been downgraded to junk bond status, kicking off a scramble to save the floundering studio. Paramount's gradual implosion has become a feeding frenzy for financial firms and media outlets, as multiple Hollywood players, private equity firms, and storied billionaires have entered the fray.

Somehow, a hundred-year-old Hollywood institution has earned an asset rating reserved for precarious upstarts like Pets.com, Bird, and WeWork. Paramount discarded its lucrative cable TV and movie businesses to get into streaming, a nascent industry with confusing economics and an unproven path to profitability. In the final quarter of 2023, Paramount lost a reported $490M on its streaming business despite hitting 71M subscribers. How can a mainstream media brand with over 70M paying customers (an outlet that regularly broadcasts the Super Bowl) be hemorrhaging so much money? Are the economics of streaming that backward? The answer is yes.

So today, we'll investigate the excessive (and inefficient) spending required to grow a streaming service and the unfortunate economic reality underlying the industry's maturation (and slow-moving implosion).

Streaming's Leaky Bucket Problem

How does a streaming service (attempt to) sustainably grow? This is the billion-dollar question plaguing the entertainment industry.

Every month, streamers like Netflix face the near-impossible task of engaging and re-engaging tens of millions of subscribers. To avoid mass cancellations, these services must deliver an eclectic mix of content to suit a diverse range of user tastes.

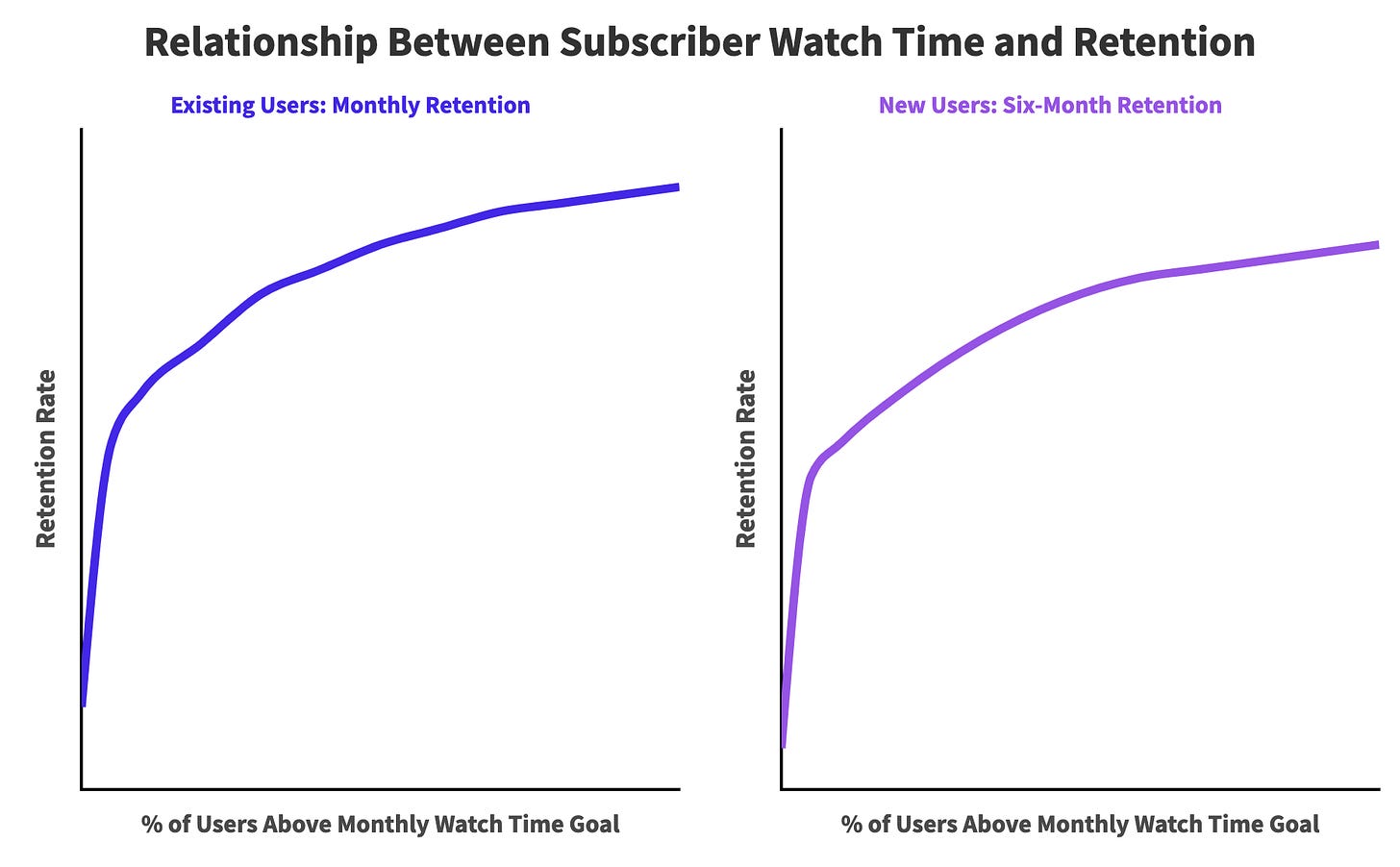

True crime, prestige movies, sports docuseries, and other niche programming appeal to various "taste clusters" in an effort to push these distinct customer segments over a weekly or monthly usage goal (i.e., how many subscribers use Netflix 20+ hours a month). As more users engage with the platform and exceed this hypothetical target, retention levels rise: existing users stay on for another month, and fewer new subscribers cancel within their first six months. We can imagine this relationship looking something like this:

For this reason, content development is both the primary driver of platform growth and the foremost catalyst for continued user retention. If streamers underinvest in content production and media licensing, they will begin shedding subscribers and inevitably shrink. Netflix, the clear market leader in streaming, has achieved across-the-board subscriber engagement through big-name prestige hits like The Queen's Gambit and Orange is the New Black in tandem with niche programming for true crime, sports, and reality TV fans.

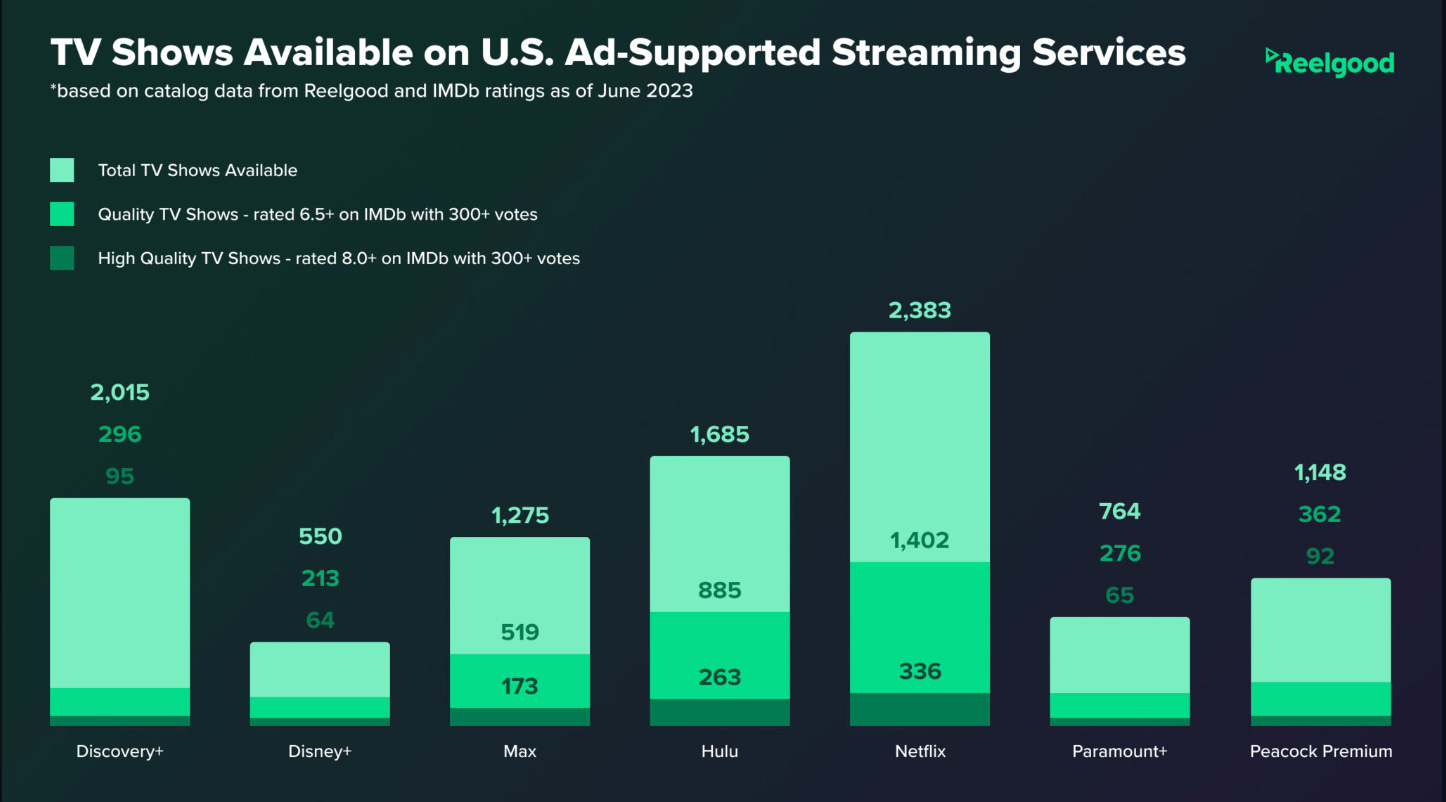

According to data from content discovery platform Reelgood, Netflix's TV catalog is the largest by a significant margin, nearly 2x-ing the number of TV titles offered by competitors like Hulu and Max.

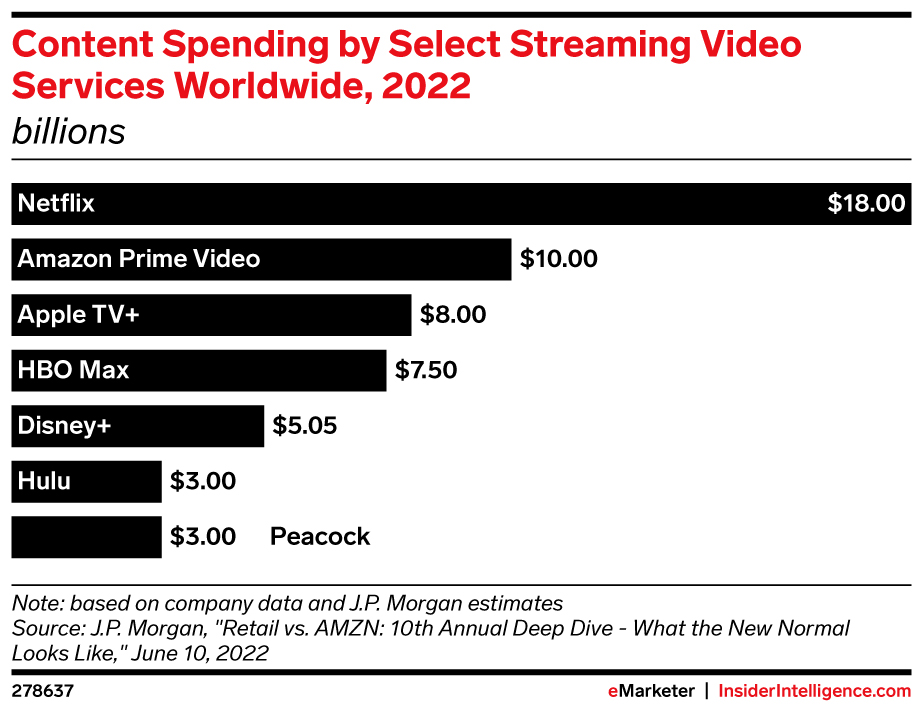

And how did Netflix achieve this mind-boggling scale? Why money, of course. According to estimates from J.P. Morgan, Netflix spent $18 billion on content in 2022 alone, lapping all other streamers by a significant margin. Peacock, the lowest-spending service during this period, still invested a ludicrous $3B to expand its fledgling media library.

What did Peacock get for this sum? I truly have no idea—perhaps it kept the service from falling further behind. And what did Netflix get for its unparalleled spending? Best-in-class user retention.

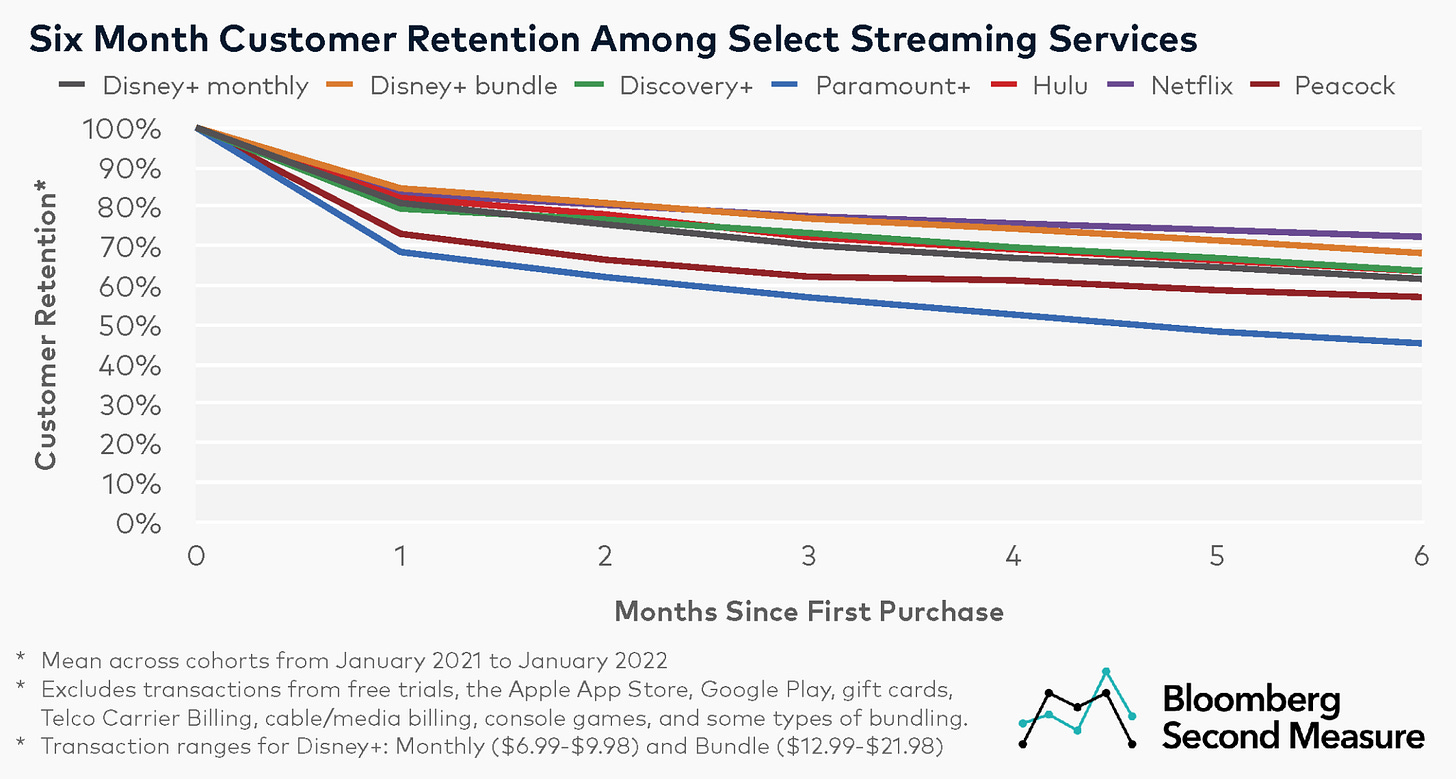

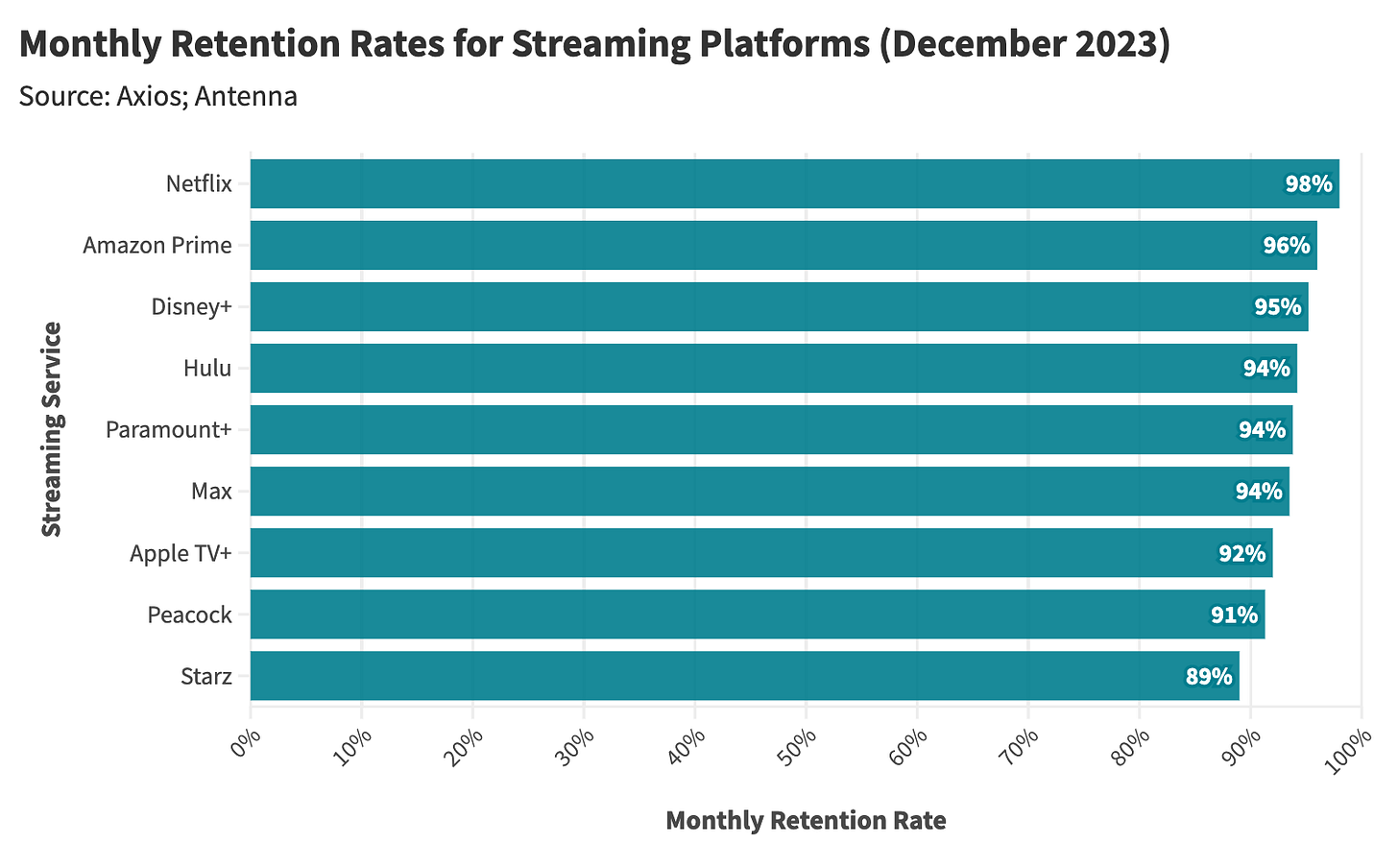

A recent Axios report on the health of streaming platforms shows Netflix greatly outpacing other services in terms of monthly retention, likely the product of first-mover advantage and a superior content catalog.

Second Measure data indicates that Netflix also leads the pack in new user retention, with a higher percentage of recent sign-ups sticking with the service in their first six months.

These stats are a testament to Netflix's strength and the overwhelming weakness of services like Peacock, Paramount Plus, and Apple TV. To underscore this disparity in business performance, we'll use these retention figures to calculate the average user tenure for each service:

Peacock: With a 91% monthly retention rate, the average Peacock subscriber only sticks around for 11 months.

Apple TV: A 92% retention rate means the average Apple TV user stays with the service for 12.5 months.

Netflix: Netflix's 98% retention rate means the average subscriber pays for the service for nearly 50 months—that's three Olympics' worth of time!

At this rate, Apple and Peacock must replace a large portion of their user base each year, which means increased investment in marketing and media production. These floundering services are leaky buckets that can only be salvaged by pouring more cash into said bucket, a financial death spiral of inefficient spending.

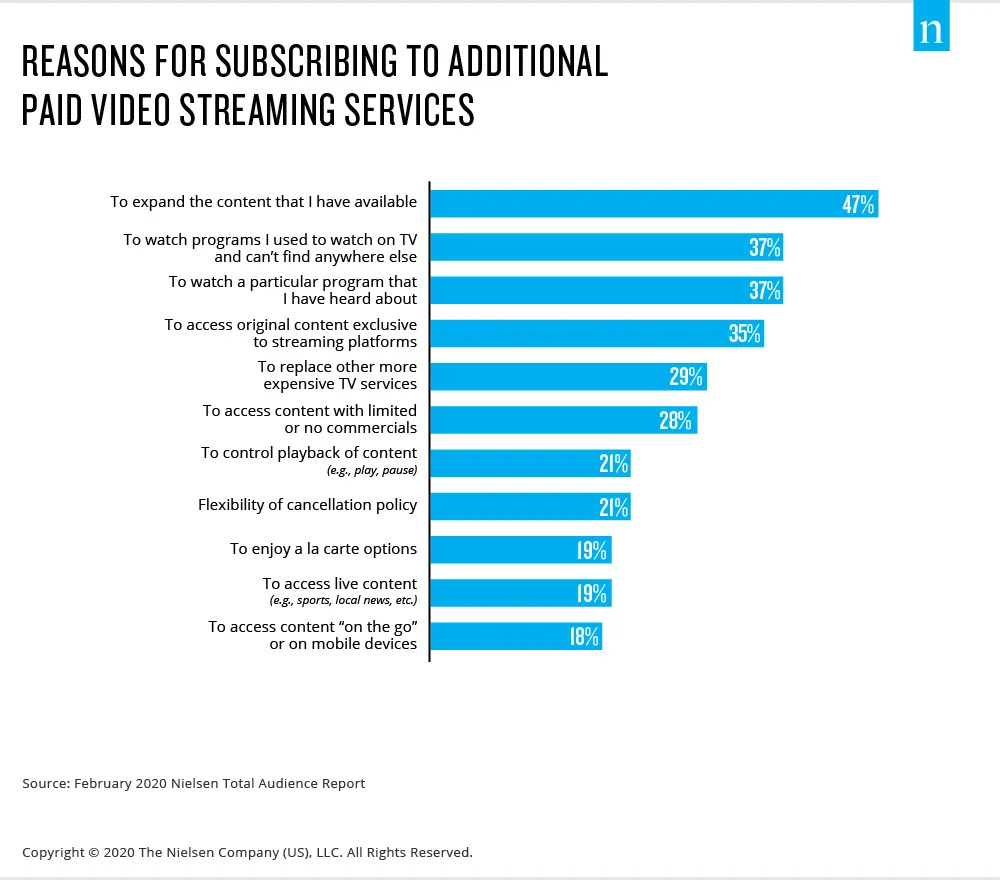

A 2020 Nielsen survey indicates that exclusive and original content is (unsurprisingly) the primary driver of streamer sign-ups, with the poll's top four responses referencing programming options as the main reason for adding another service.

Price cuts and flashy marketing cannot compensate for a subpar content catalog. This conundrum puts laggards like Apple, Peacock, and Paramount in a lose-lose situation, as they have no choice but to spend their way to growth and retention despite knowing that (in the short term) a high percentage of newly acquired subscribers will cancel. Apple TV must produce several Ted Lasso-like hits to keep pace with Netflix (or even just Hulu), while in Peacock's case, I legitimately don't know what people watch on this service, so they probably need about 20 Ted Lassos.

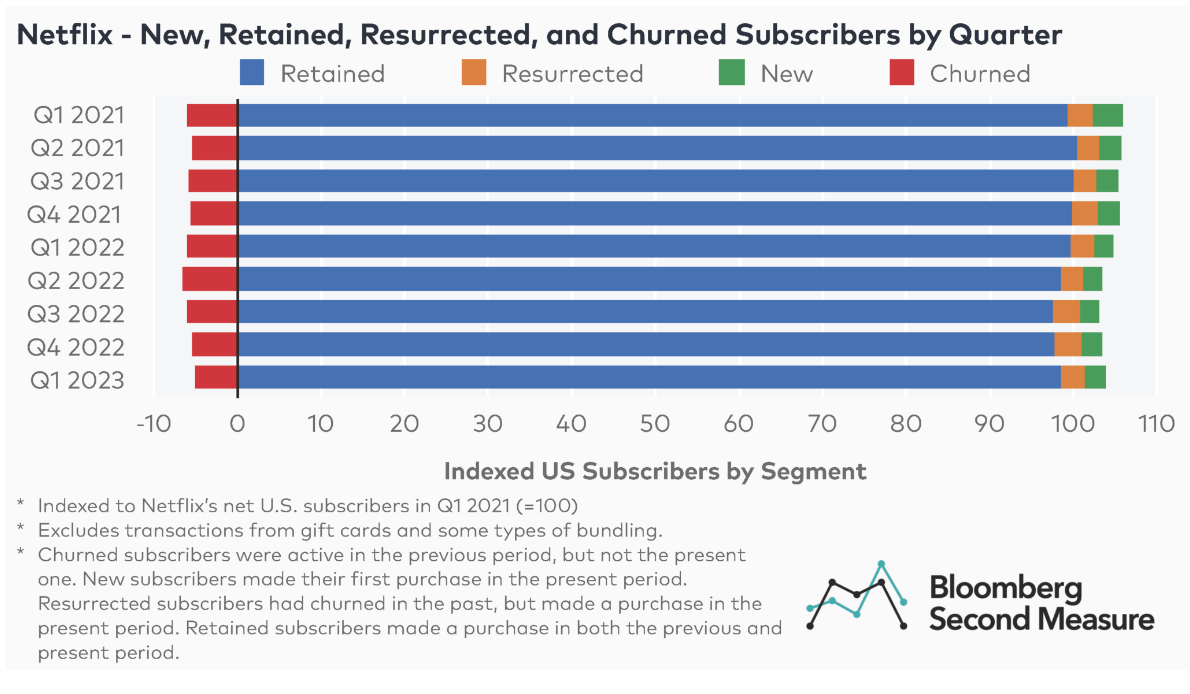

Even worse, a big hit like Ted Lasso may prove a one-time boon for customer acquisition, but that doesn't mean these users will stay forever. By offering no-hassle monthly subscriptions, streamers like Peacock and Apple TV have fostered a fickle base of yo-yo customers who continuously cancel and resubscribe to the same services. A Second Measure analysis of Netflix retention and acquisition reveals a substantial quarterly cohort of reactivating users (termed "resurrected" in the graphic below), meaning the service regularly acquires and re-acquires the same customers.

This dynamic pales in comparison to legacy cable businesses, where buyers sign up once and stick around for years (as opposed to days or months). The initial promise of streaming television—high-quality content, no annual contracts, lower prices—has led to ludicrous debt spending, scarce customer loyalty, rising prices, and an unproven path toward sustainable growth. And yet, somehow, the economic viability of this business model will only worsen as the industry matures.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Diminishing Returns: Where Streaming Economics Really Break

So far, the relationship between content and business performance seems pretty straightforward: the more subscribers watch, the more retention, acquisition, and reactivation improve. All these streamers need to do is produce a wide array of high-quality content on a monthly basis, and they'll win the loyalty of once-fickle customers while simultaneously becoming profitable—a totally achievable and not at all difficult task. Why hasn't every streamer done this, and why are all these services struggling so mightily with growth despite their ever-expanding content libraries?

Much of this dysfunction stems from a rather unfortunate paradox: in the backward world of streaming, an hour of subscriber watch time doesn't actually equal one hour. If you're confused, know you're not alone—this unfortunate reality has effectively torpedoed the entertainment industry.

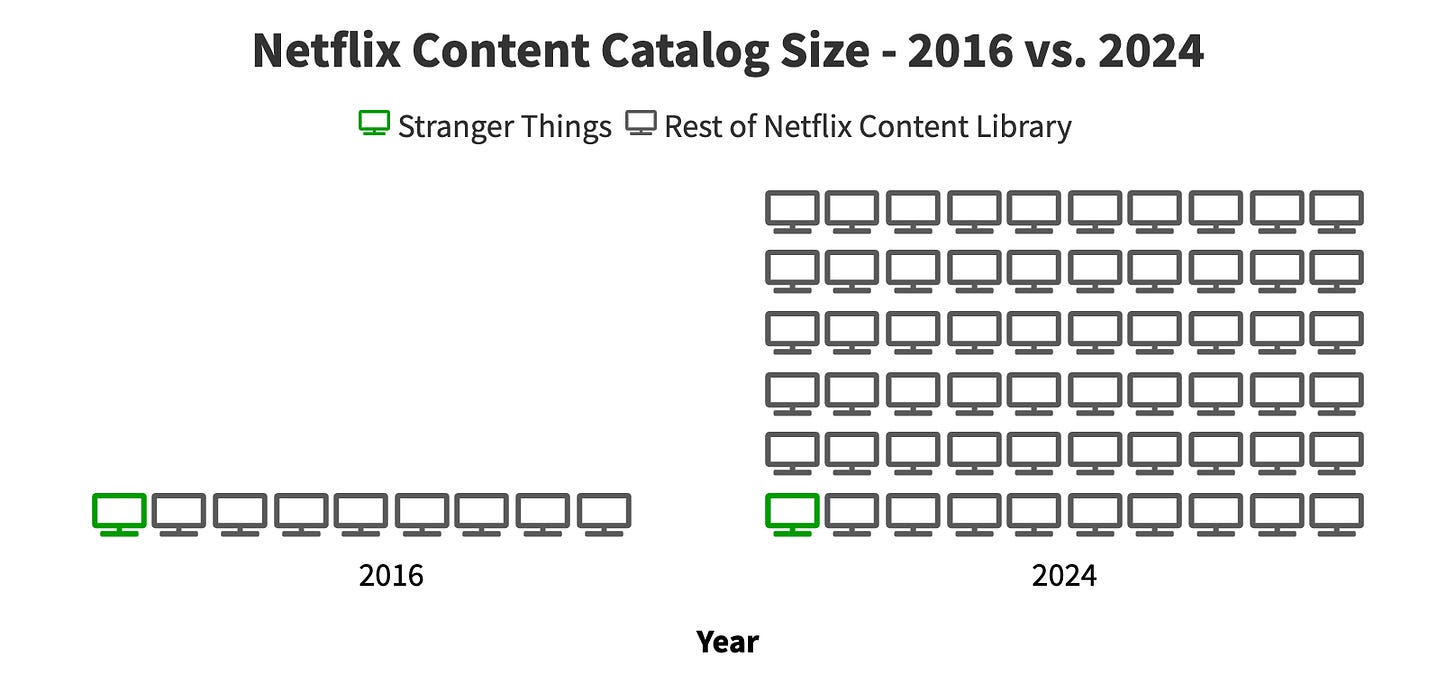

Consider the value of Stranger Things season one versus Stranger Things season five. The show's first installment dropped in 2016 when Netflix had a significantly smaller content catalog. At this point in time, Stranger Things was a big fish in a small pond, driving a disproportionate share of streamer watch time. Stranger Things' final season, released in 2024, will undoubtedly accrue significant viewership, but it's now one title in a sea of thousands.

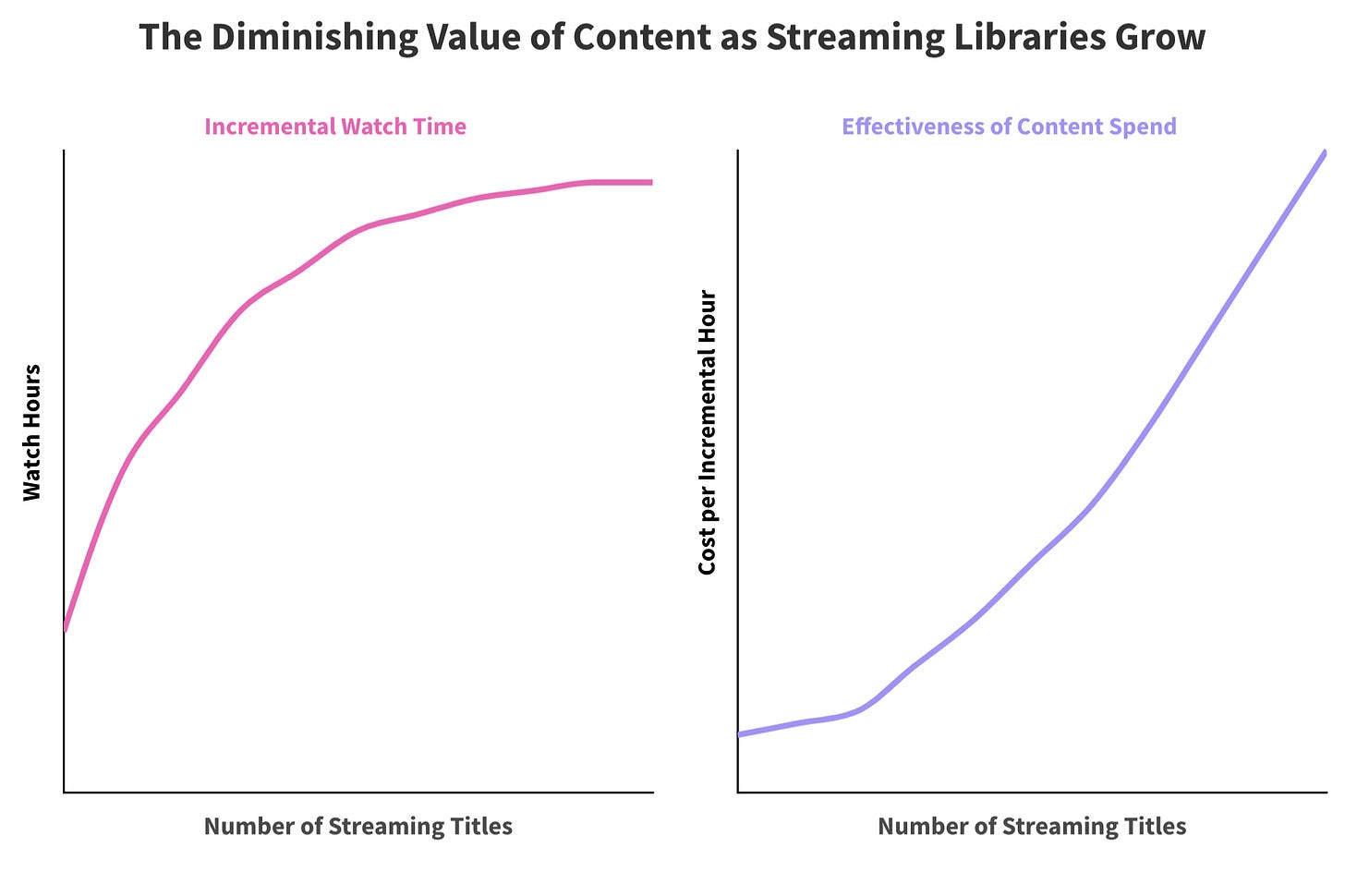

Season five may garner more watch time, but season one will always be more valuable. This is a common issue for most marketplace businesses—the problem of diminishing returns. With each title addition, every subsequent addition is less valuable.

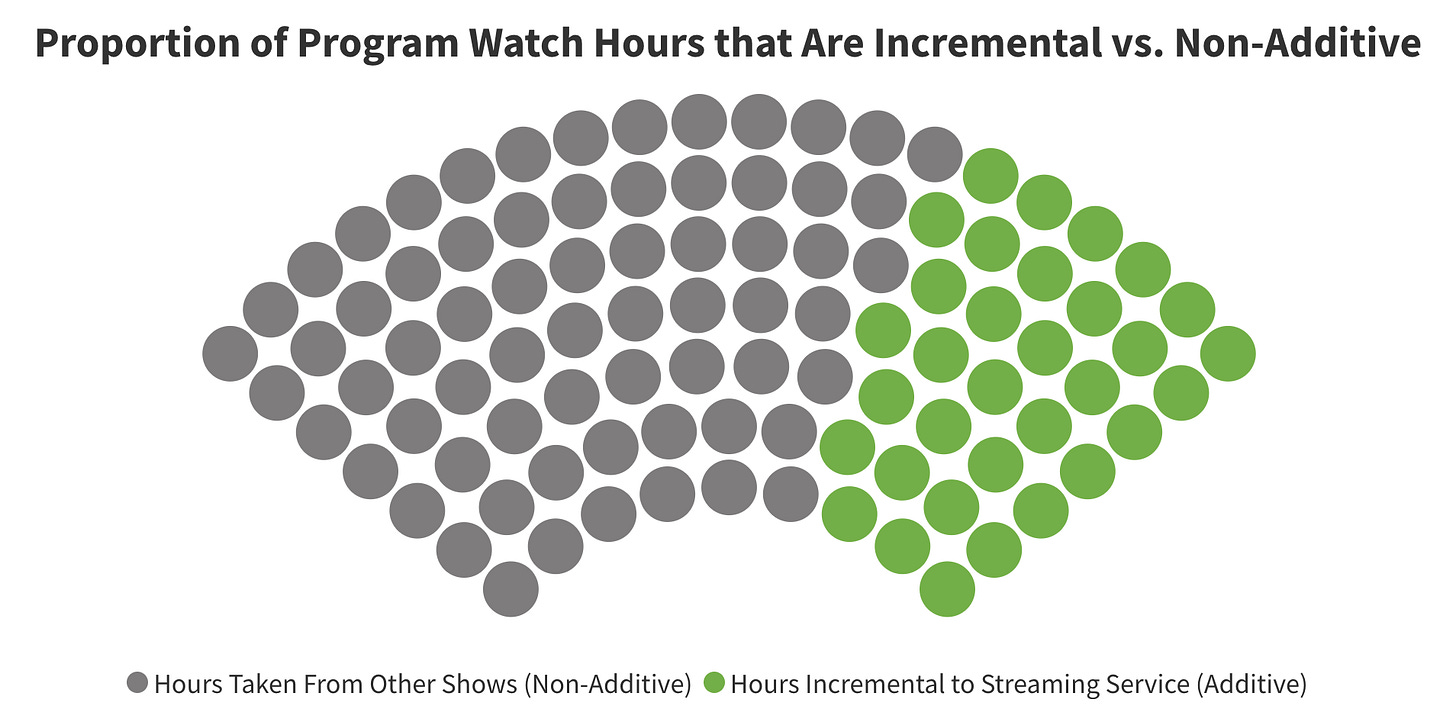

This conundrum largely centers around incrementality—in this case, watch time incrementality. To underscore this point, we'll broadly segment show watch time into two buckets, non-additive and incremental:

Non-additive Hours: You were scrolling through the Netflix home screen and happened to land on Love is Blind. You think, "Why not?" and you watch this show. You would likely spend time on Netflix even if Love is Blind didn't exist, and you would undoubtedly subscribe for another month absent this show's presence. Your Love is Blind viewership simply took hours away from another show you might have watched instead, like Too Hot to Handle and Is it Cake?.

Incremental Hours: You sign up for Netflix just to watch Love is Blind and consistently re-up on the service because you love watching this show. Without Love is Blind, you would not pay for Netflix.

Incrementality varies significantly across content, but at a high level, you can imagine a world where only a portion of every 100 watch hours is truly additive to the platform.

This is where the economics of streaming really go off the rails.

When it comes to incrementality, value is heavily determined by the point at which a show is added to a streamer's catalog. Each addition to Max or Hulu's content library makes less and less of an impact. At the same time, streamers must continue their exorbitant spending to keep pace with Netflix and satiate our need for prestige television. Unfortunately, this excessive investment becomes increasingly inefficient, with each dollar spent on flashy content yielding less additional watch time, thus raising the cost of attaining incremental hours.

This economic reality presents streaming services with three options:

Implode: Like Paramount.

Produce Less Content: If you produce less content, you'll lose less money (you heard it here first!). That said, if you spend less, you'll acquire fewer users and retain a smaller share of paying customers. Once this happens, Wall Street will write you off as a failure, your stock will tank, and you'll be fired—just like the head of Paramount.

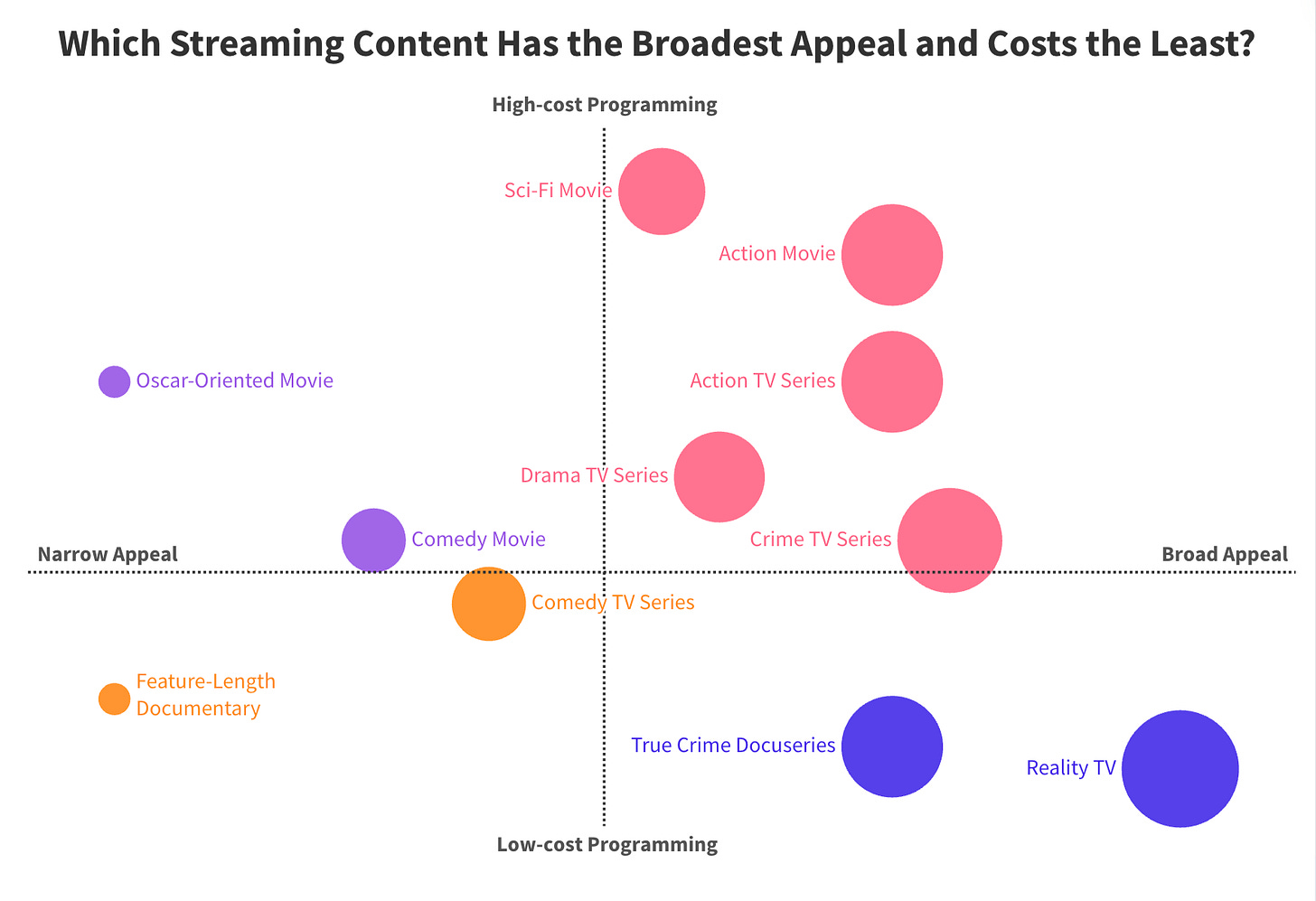

Produce Cheaper Content: Not all content is created equal. Some content has broad appeal, and some properties are cheap to produce. As the streaming industry evolves, we'll see increased investment in inexpensive concepts with wide appeal.

We can envision a 2x2 of content cost versus programming breadth of appeal and then sort various genres and story formats within this matrix. Naturally, a mature streamer like Netflix gravitates toward true crime docuseries and reality TV shows, low-cost concepts with surprisingly broad audiences.

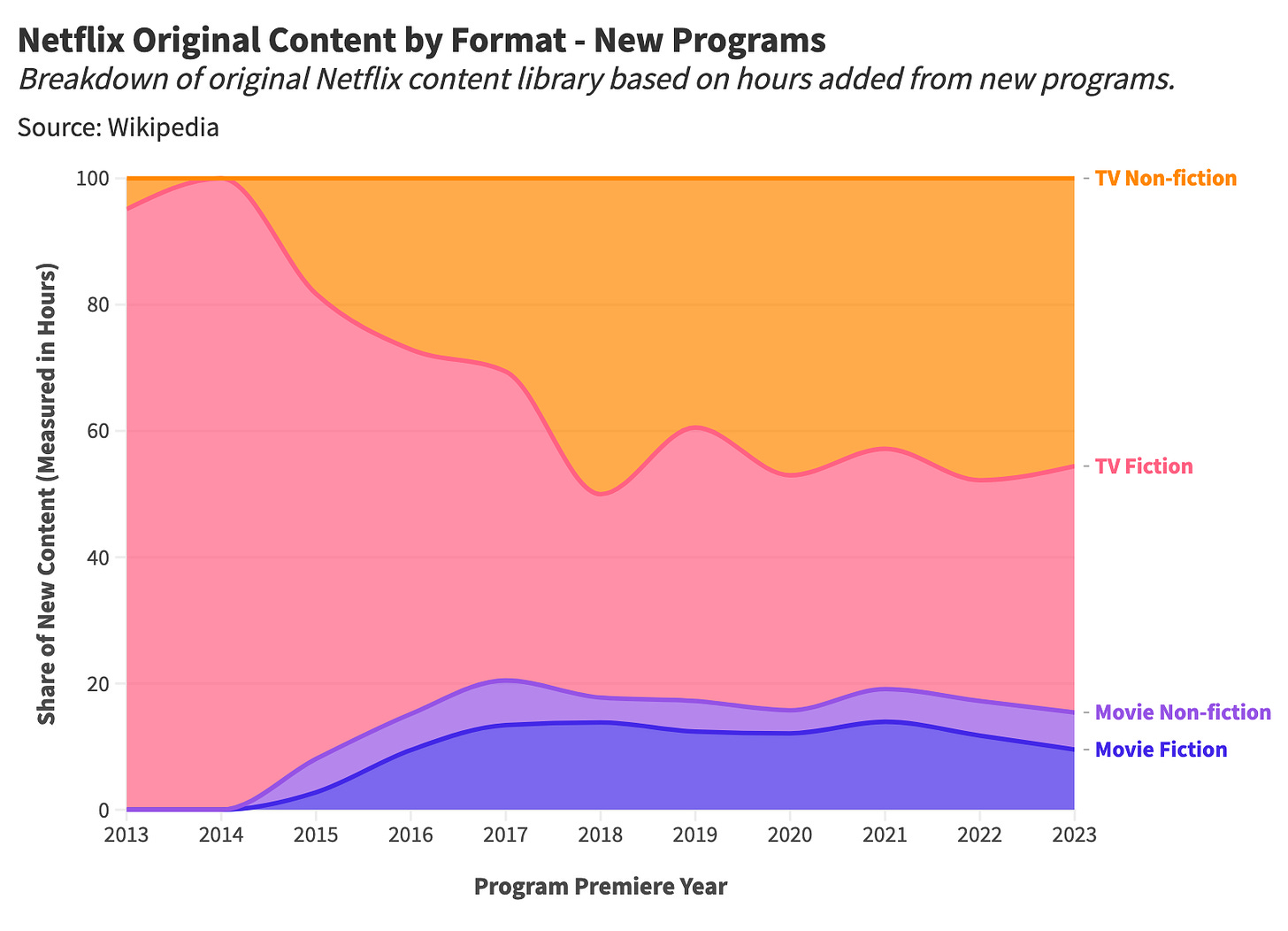

Throughout the past decade, Netflix has ramped up its investment in serialized non-fiction with series like Making a Murderer, Is it Cake?, and Too Hot to Handle. Over time, Netflix's content mix has skewed away from narrative dramas and comedies toward low-budget non-fiction.

In retrospect, this shift to cheaper programming was inevitable. Streamers burn through cash early in their lifecycle, producing blockbuster properties like Masters of the Air and Fallout to acquire and (hopefully) retain subscribers, chasing Netflix's absurd scale. Once a platform hits diminishing returns, the service begins pursuing efficiency and profitability (whatever that means)—a world populated by dating game shows and Jeffrey Dahmer documentaries.

And sure, you may think you're better than this content but guess what—you're not. You'll watch the 10th cheaply produced true crime Jeffrey Dahmer docuseries, and you'll love it because you're a sicko like everyone else. You'll pay your $15, and perhaps you'll learn a new bit of Dahmer lore—that's entertainment at its finest.

Final Thoughts: Free Delivery Forever?

I moved to San Francisco in 2015 during the height of the app boom. This period was marked by an ever-proliferating ecosystem of startups, each with nonsensical free delivery coupons and lucrative referral incentives. San Francisco, the epicenter of this entrepreneurial boom, saw an influx of upstarts with unsustainable business models that channeled their VC funding into ridiculous marketing schemes.

It was a fantastic time to be a recent college grad with no money. At one point, my roommates and I tried to go a week without paying for food or transportation, funding our lives with startup marketing incentives. We ordered delivery with coupons from Sprig (now defunct), Munchery (out of business), and Eat24 (acquired), and we traversed the city via Uber (still alive), Sidecar (shut down), and Chariot (gone forever). These companies vowed to grow first and then figure out profitability later. If it all seemed too good to be true, that's because it was.

The first decade of streaming has been no different. Services like Peacock and Max have focused on growth at all costs with little understanding of future viability. And yet, somehow, we thought peak TV would continue indefinitely—that this wasn't too good to be true.

Worse still, there's no going back. Viewers have become accustomed to an abundance of high-quality content, a far cry from the days of CSI: Miami and How I Met Your Mother. So, where do we go from here?

An economic principle known as Chesterton's Fence states that people should not change something until they understand the reasoning behind the current situation. You could easily apply this doctrine to television: why was cable TV the way it was, and what did we lose by cutting the chord?

A common sentiment in entertainment trade publications is that the future of streaming is cable TV. What does this mean?

Advertising

Subscription bundling

Higher prices

Low-cost content

When all is said and done, Hollywood will have cannibalized lucrative cable and moviegoing businesses to reinvent a less lucrative cable TV business. In the process, the movie industry will have shrunk and several studios (like Paramount) will have failed. Maybe I'm wrong, and streamers find a more sustainable business model while maintaining an abundant output of high-quality content. Or maybe this screed is simply the ramblings of a person who is angry about paying ~$120 a month for a slightly better version of cable.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Hmm, I think you're missing a couple of things though.

First, why does it have to be new content every month? Paramount has a huge library of old content - more than your average viewer can consume. Why isn't that sufficient to retain and acquire customers?

Second, re cheap content, it doesn't have to be cheap in total, it's the marginal cost that counts. Making mission impossible films is ludicrously expensive. Adding them to Paramount+ is almost free. So by this logic, studios should have an advantage over netflix, since the marginal cost of their subscription services are lower.

Thanks for finally clarifying the economics of streaming. I really never understood it. Netflix spent $18B for new content why? So they retain 98% of their users—an astonishing number. Netflix has really built a content moat. I like the stock 😉.