Is TV's Golden Age (Officially) Over? A Statistical Analysis

Has "Peak TV" come to an end?

Intro: Is "Peak TV" Behind Us?

A lot can change in forty-five months. Think back to November of 2021: the world had yet to see a Tesla Cybertruck, HBO Max was an ascendant streaming service, Will Smith had slapped zero people on live television, Sam Bankman-Fried was a benevolent billionaire and model citizen, and Netflix's stock was soaring, buoyed by the pandemic.

And then the unthinkable happened: Netflix reported a quarterly loss of 200,000 subscribers. This earnings miss—coupled with broader economic uncertainty—triggered widespread panic across the entertainment industry. Streaming platforms slashed their content budgets, media conglomerates like Disney and Warner Bros. laid off thousands, and Netflix's stock fell by 51%. This industry-wide contraction culminated in a six-month writers’ strike, as unions demanded higher pay, standardized compensation, and greater residuals. Amid full work stoppages and a volatile economy, industry pundits began speculating whether streaming could recapture its pre-2022 momentum.

Fast-forward to 2025: Netflix's stock price has increased 500%, there's still a streaming service called HBO Max (despite the platform having changed its name multiple times), and the world is full of Tesla Cybertrucks.

Two years removed from the 2023 writers’ strike, the entertainment industry remains in flux—uncertain whether it has regained its footing or if the "Peak" in "Peak TV" is now behind us.

So today, we'll explore how streaming output has changed since the 2022 slowdown and 2023 writers’ strike, and how consumers have responded to these strategic shifts.

Is TV's Golden Age Over?

If such a job exists, TV historians will point to two shows as harbingers of "prestige television."

The Sopranos: HBO's landmark crime drama blurred the line between film and television, pioneering a cinematic approach that redefined what TV could be. With its elevated production value and narrative ambition, the series embodied HBO's value proposition as a premium service. It wasn't TV; it was HBO. 😎

House of Cards: Netflix's first original series signaled the promise of a new medium—prestige content delivered on-demand, bingeable, and entirely free of commercials. The show marked a shift in how streamers would grow: not by licensing content, but by producing must-watch television.

Over the next decade, streaming services competed to deliver buzzworthy prestige hits. These glossy shows were seen as the industry's primary growth engine, which justified their considerable cost. For viewers, it was a golden age marked by high-end cinematic television available for cheap or sometimes free: Orange is the New Black, Severance, Squid Game, Stranger Things, The Bear, The White Lotus, Mare of Easttown, Fleabag, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, and countless shows that were unsustainably awesome.

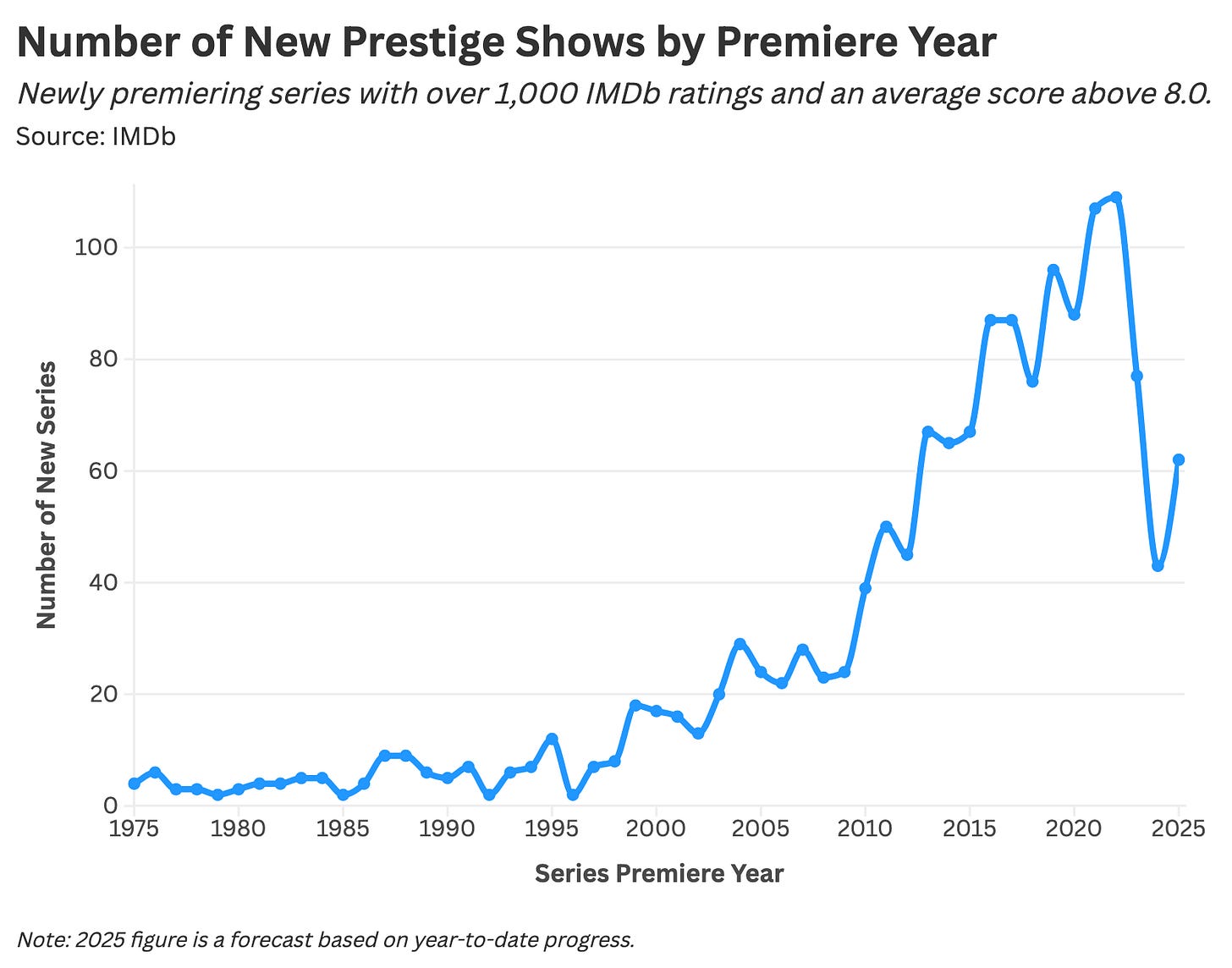

Then Netflix's stock plummeted, the writers' strike hit, and the streaming industry entered an era of austerity. The production of prestige content—as measured by above-average IMDb series rating—began to slow. Since 2022, the number of new buzzworthy shows has dropped sharply.

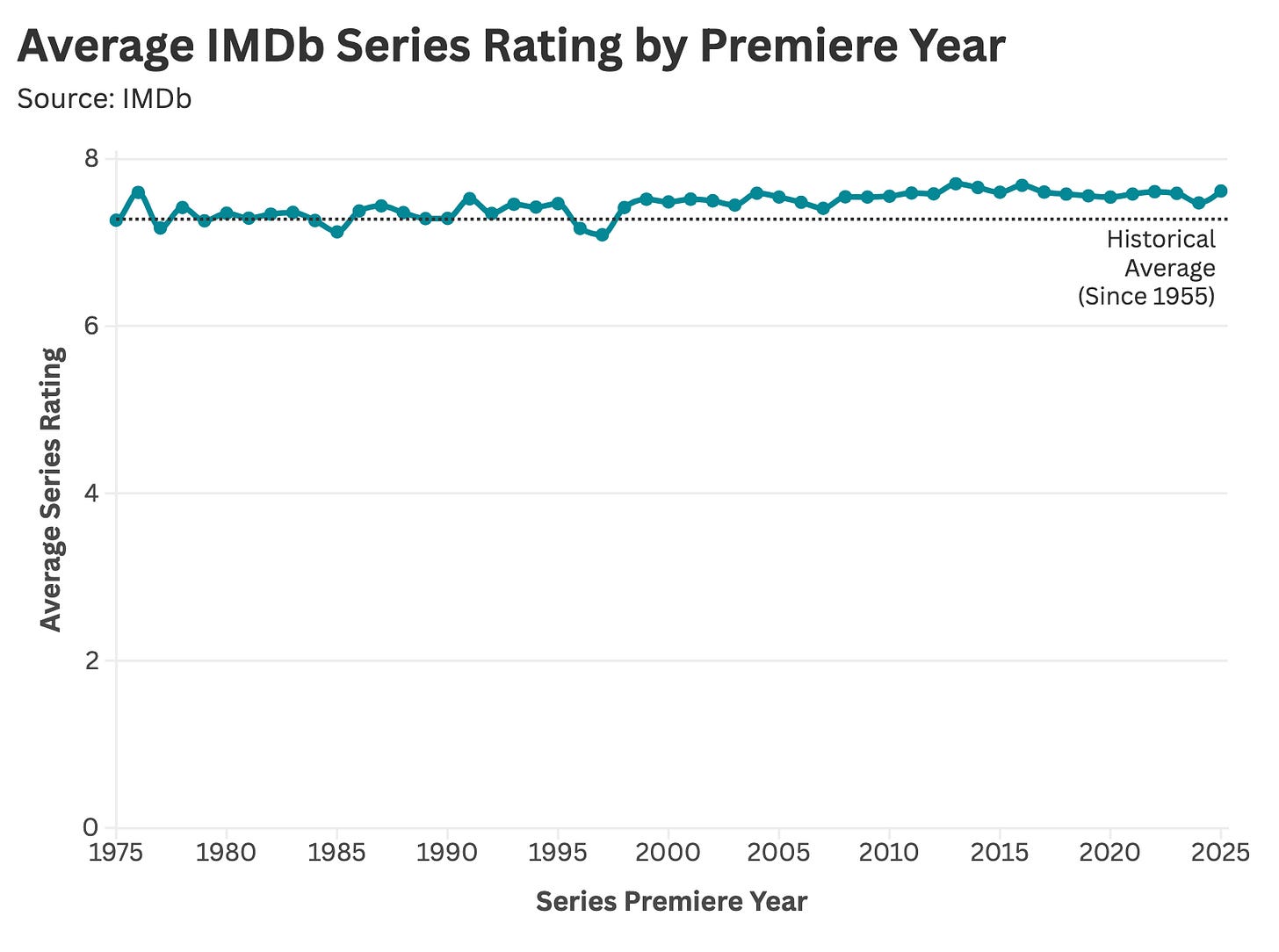

So what changed—content volume or quality? According to IMDb ratings, we see a sustained rise in series acclaim beginning in the early 2000s (on the heels of The Sopranos), a trend that has continued to this day.

TV is still as good as it's ever been—people are trying their hardest!—which means the decline in buzzy content stems from production volume.

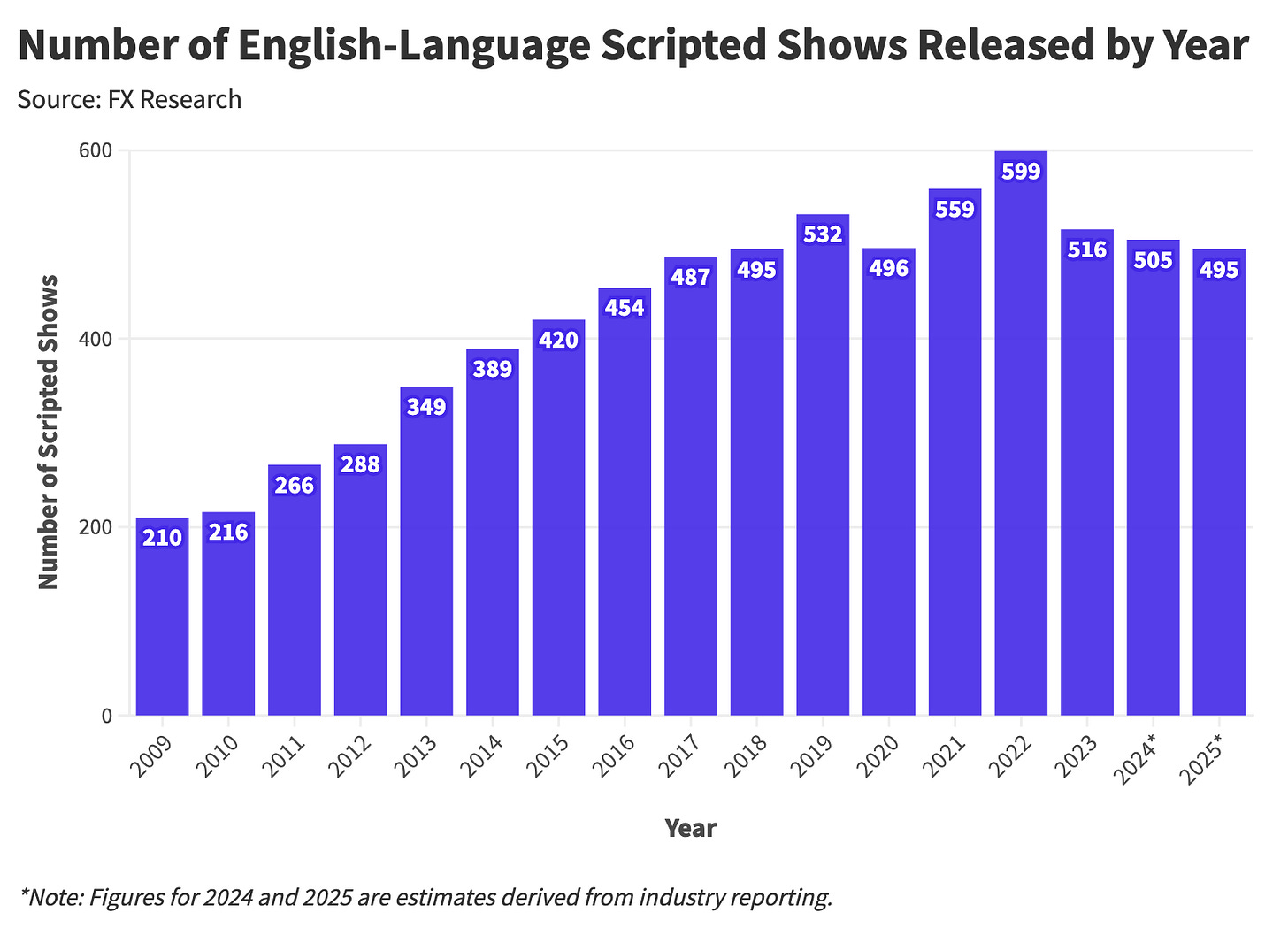

In 2015, FX CEO John Landgraf coined the term "Peak TV" to describe the rising number of scripted television series. Industry pundits immediately embraced the term, framing the executive as some all-knowing prophet. All credit to Landgraf for superior branding, but I'd argue his "Peak TV" observation was less prescient than it was painfully obvious. Who better to comment on the unsustainable pace of content production than an executive who is being told to produce content at an unsustainable pace?

Since 2009, FX's research division has tracked the production of English-language scripted shows, producing an annual report that serves as a proxy for the industry's spending appetites. According to this count and industry forecasts, the proverbial "Peak" of the "Peak TV" era occurred in 2022.

This production slowdown stems from two industry trends:

Streamers Focusing on Returning Shows: The content development strategy of the late 2010s can best be summarized as "throwing [stuff] at the wall and seeing what sticks." This process, while inefficient and expensive, yielded some winners. As the industry has matured, streamers have shifted their focus from generating buzzworthy programming to funding series that successfully achieved buzz. In turn, these returning programs have broadened their scope, leading to ballooning budgets. The second season of Severance reportedly cost $200 million, and the fourth season of Stranger Things racked up $270 million in expenses.

Fewer New Shows: New shows are risky, especially when you could fund a proven winner for that same budget.

This lack of novelty gives the impression that networks have stopped trying, but this process was inevitable. Netflix, Amazon, and Apple started their streaming services without a catalog of original programming; they had no choice but to spend aggressively in pursuit of flashy content that would justify a subscription.

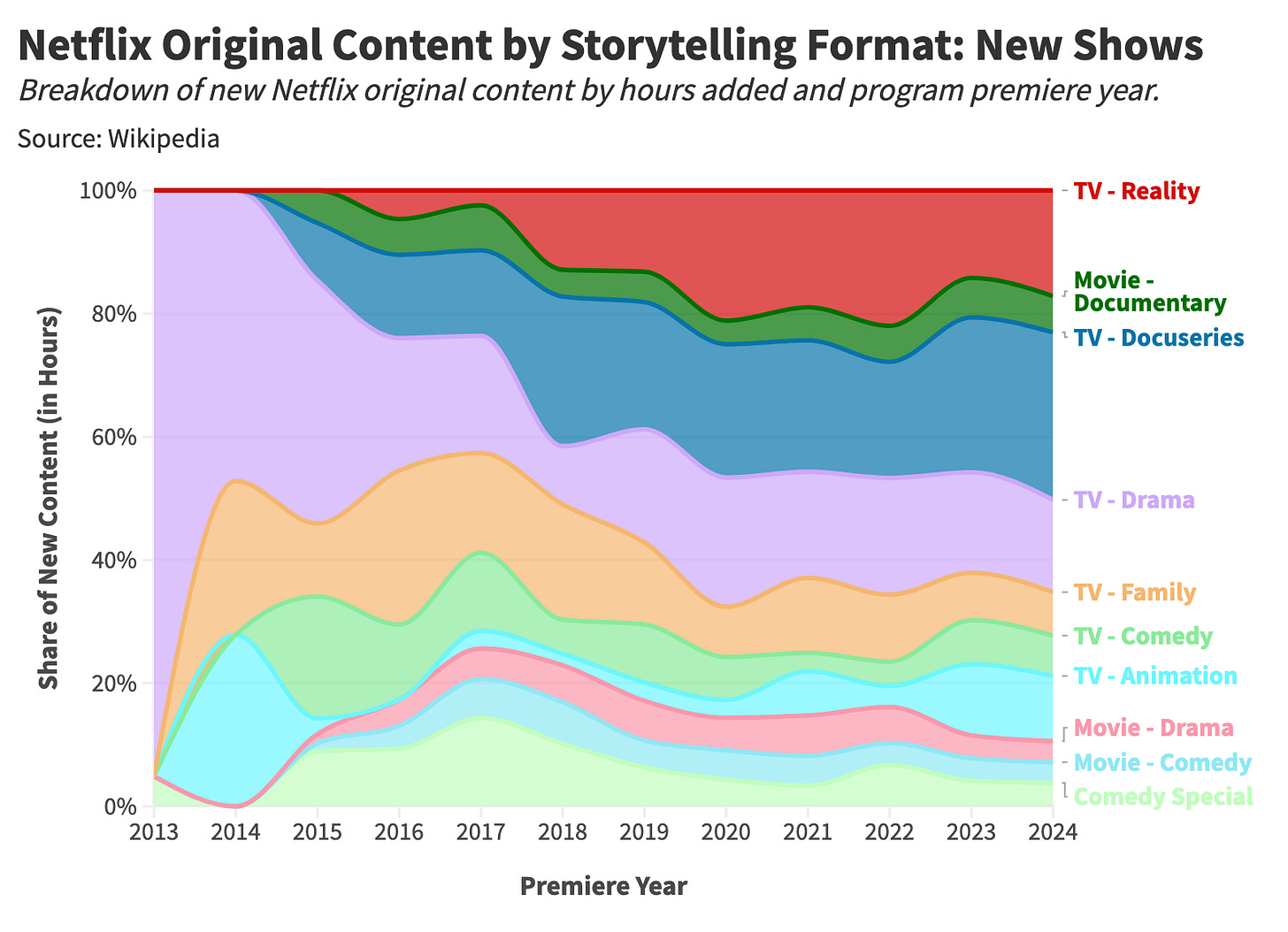

The post-2022 slowdown arrived as audiences were watching more TV than ever, while being served fewer scripted shows. So how did streamers keep viewers engaged while cutting back on narrative content? With low-cost unscripted television—the very opposite of the prestige content we were first promised.

Since 2018, Netflix has expanded its catalog with low-cost docuseries and reality shows, making nonfiction the majority of its content output.

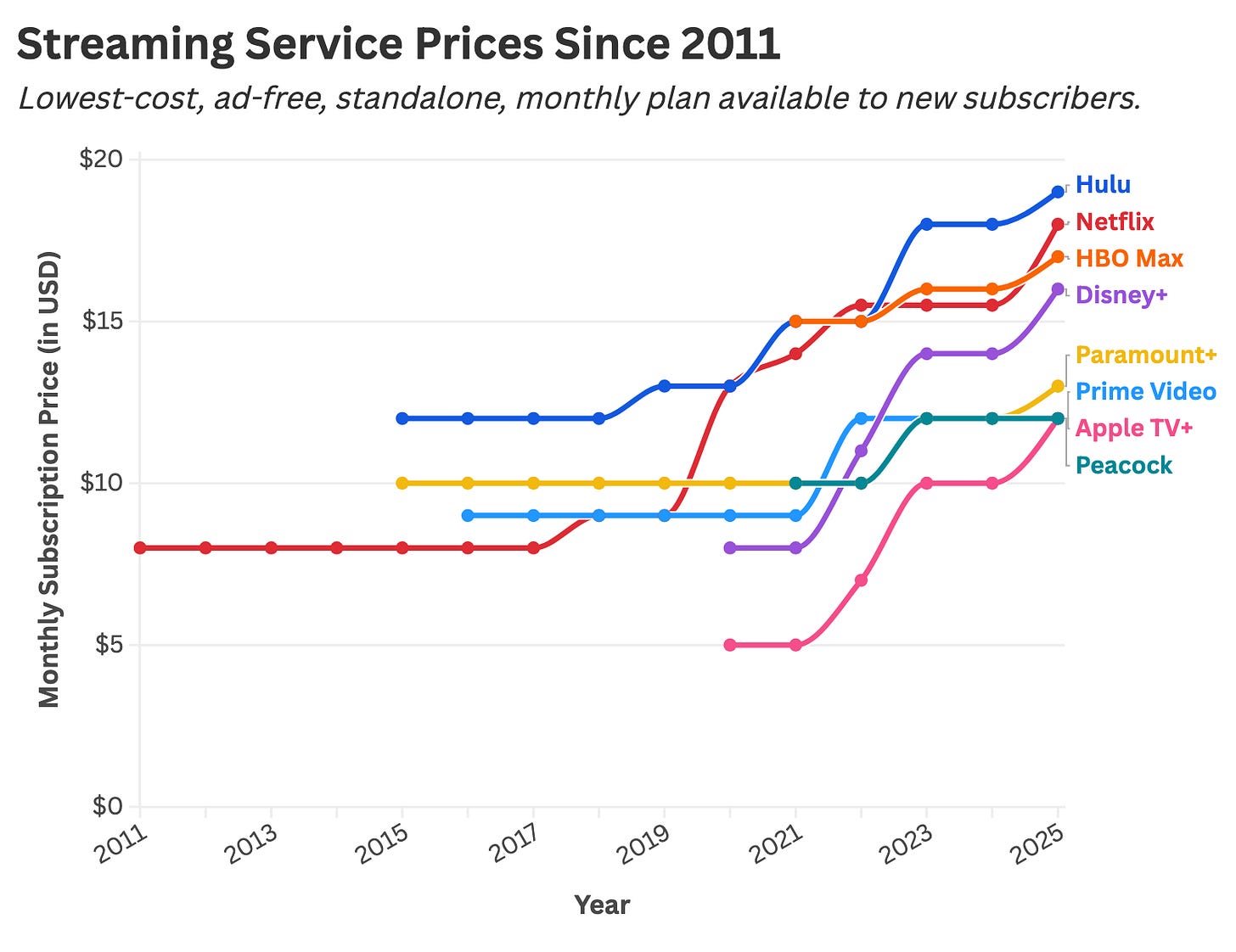

This content retrenchment has coincided with an industry-wide increase in subscription pricing. Charts that go “up and to the right” tend to delight our lizard brains—but this one is an obvious exception.

So, how have people responded to paying more while receiving less? By gravitating to free stuff.

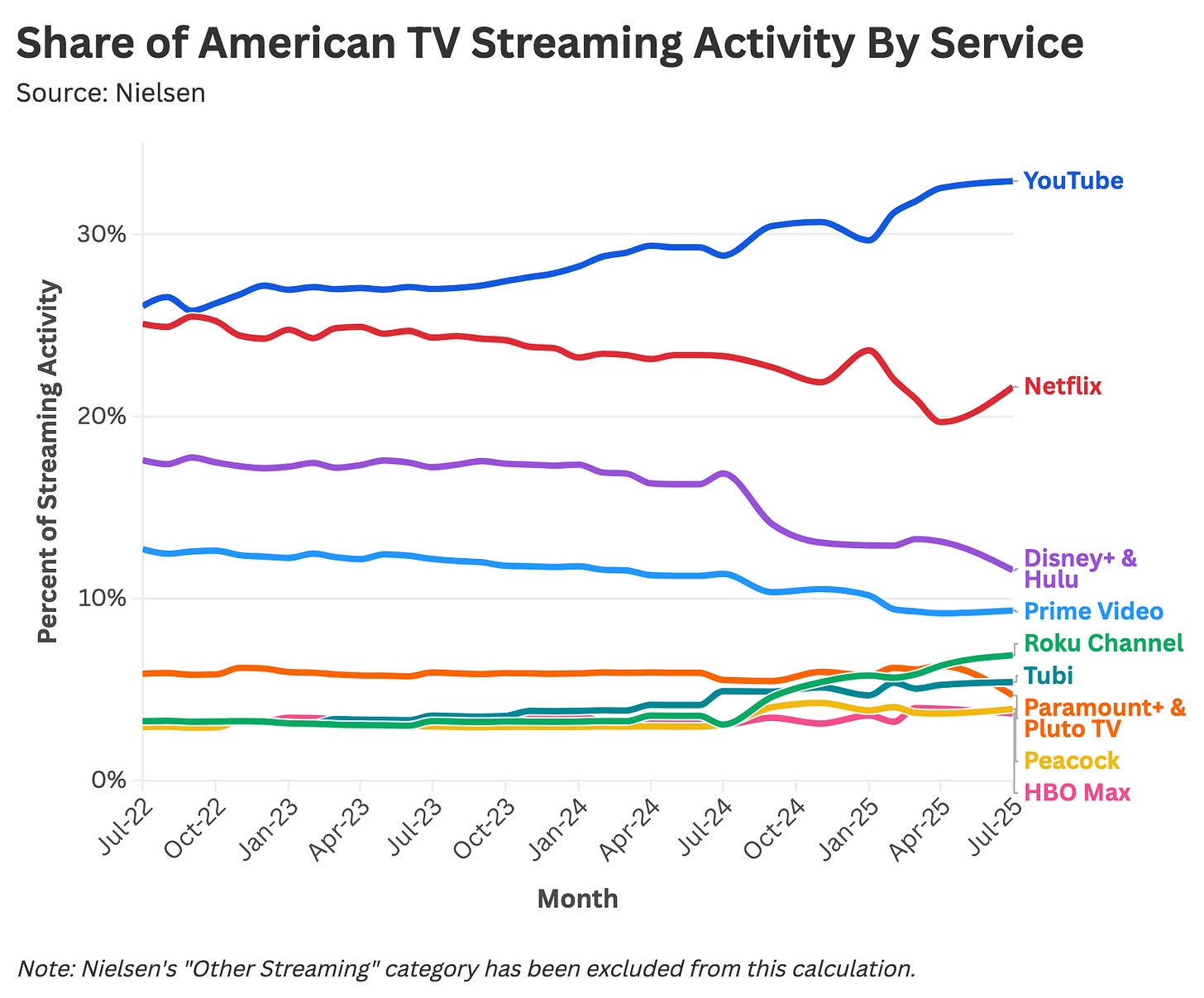

If you asked someone, "Who is winning the streaming wars?" and gave them ten guesses, they would never name the frontrunner because it's not a Hollywood studio. When people turn on their TVs, they're more likely to open YouTube over Netflix, Paramount+, or Hulu.

If you look closely at this chart, you'll notice that the platforms with increasing share are YouTube, Tubi, and The Roku Channel, which are all free, funded entirely by advertising. After years of rejecting commercials, consumers are once again willing to sacrifice time over money.

Meanwhile, YouTube has built an entertainment juggernaut: one that is free, powered by creators who are willing to work for meager ad revenue and the promise of social capital.

For now, the streaming industry is still expanding, which means these companies will grow as long as they maintain market share (or lose market share slowly). But eventually, cord-cutting will plateau, YouTube will keep gaining ground, and a second wave of streaming consolidation will occur.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: The Return of Cable TV

This past week, I started watching a buzzy series on HBO Max called Task. This show has all the makings of prestige programming: high-end production value, a big movie star (Mark Ruffalo), complex antiheroes, and a marketing campaign that repeatedly reminds you that this series is "from the creators of Mare of Easttown." This show is good—I would even recommend it in casual conversation—but it also bums me out. Had this been delivered to me in 1998, I would have heralded its arrival as an unqualified masterpiece. But in 2025, it's just another prestige crime drama in the lineage of True Detective, Big Little Lies, Sharp Objects, and, of course, Mare of Easttown. It's a run-of-the-mill high-end crime show.

My disappointment is no fault of HBO or Task's showrunners, so much as it's a product of misguided expectations. I assumed television's creative evolution would continue indefinitely. As cable gave way to premium subscriptions and then streaming, I expected new formats to keep emerging and shows to grow increasingly complex. But at least for now, television has plateaued, and its content is no longer evolving.

With each new medium, be it HBO or Netflix, comes new TV formats. What sets the streaming era apart is that a content model was created before a sustainable business model was affirmed. This backwards approach to business development stems from Silicon Valley, and is best captured by a handful of jingoistic maxims endlessly recycled by LinkedIn try-hards:

"Don't ask for permission, ask for forgiveness."

"Go big fast."

“Put your money into FTX—Sam Bankman-Fried is a super credible dude!"

"Fail fast, fail often."

"Move fast and break things."

So what's been broken amid all the fast-moving and going-big?

Cable TV is dead.

Content is scattered across competing platforms with ever-increasing prices.

These competing platforms cannot sustain their content output and price point.

I have to pay for seven streaming services to watch NFL football games.

And how will all this be fixed?

Advertising

Industry consolidation through mergers and acquisitions

Bundling

Low-cost unscripted programming

If all this sounds familiar, it's because I've just explained the hallmarks of cable television. The omissions of commercials and bundling were once marketed as differentiators for streaming; now, these strategies will enable platforms to sustain themselves in the long term.

The entire ordeal—from the moment Netflix launched House of Cards—reeks of "Chesterton's Fence," the principle that one shouldn't dismantle an existing system (the proverbial "fence") without first understanding why it was built. The entertainment industry abandoned commercials, low-cost content, and economies of scale without ever asking why those strategies had emerged in the first place.

In the end, cable will reconstitute itself—this time with marginally better content and slightly more siloed offerings. Consumers will grow weary of paying more for less and will gradually migrate to YouTube, which has quietly built the most sustainable streaming platform. And perhaps, most importantly, HBO Max will cease to exist when it takes its final form as HBO-Paramount-Tubi-Disney-Peacock-Roku-Plus-Max-Plus.

Have a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Struggling to turn your data into actionable insights? Need expert help with a data or research project? Well, Stat Significant can help.

We help businesses with:

🔍 Insights That Improve Performance: Turn raw data into strategic intelligence that guides smarter decisions.

📊 Dashboards That Drive Action: Transform your data into clear, interactive dashboards, giving you real-time insights.

⚙️ Data Architecture That Automates Reporting: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

I also don't want to wait 2 years for a new season of every single show.

I would argue that the streamers were burning expenses producing shows, thinking that spending more means quality. Older streamers, and we do exist, are not as interested in prestige from glitz, but from quality programming. Otherwise, HBO MAX, which could produce three shows for 5 years on the money it wasted rebranding itself multiple times, would not still be getting people binging The Wire and The Sopranos. Netflix introducing shows, only to cancel them after a year or two, even if they are moderately sucessful, will only cause people to not invest in shows when they first debut, further speeding up the cycle. Duster, the Waterfront, FUBAR, all were modest successes that were canceled too soon. Yet Paramount continues to overpay for Tulsa King, which with the names involved, has to be an expensive show to shoot.