Is Music Stardom in Decline? A Statistical Analysis

Is music stardom dying?

Intro: The Billboard Charts, Then and Now

Every artistic medium has a widely accepted marker of commercial success. Movies have box office receipts; TV has the Nielsen ratings; music has the Billboard Charts. Yet Billboard's status as a yardstick for popular music is surprising when you consider the publication's origins.

Billboard Magazine was first published in 1894. Originally named "Billboard Advertising," it was founded to be a trade publication for the bill posting business, a common form of street advertising at the time—hence the name Billboard.

The magazine's early focus had nothing to do with music and mainly covered topics like:

Bill posting industry news (I don't really know what this means)

Traveling fairs and carnivals

Circuses and other outdoor amusements

Over time, Billboard slowly moved away from street advertisement in favor of music culture:

In 1913, Billboard began tracking sheet music sales.

In the 1920s, the magazine began covering radio.

In the 1940s, Billboard introduced its first music charts, tracking pop, rhythm & blues, and country.

Finally, in 1958, the publication launched the "Billboard Hot 100," a weekly ranking of America's most popular songs based on aggregated data from album sales and radio airplay.

The Hot 100 quickly became the industry standard for tracking hit songs and has remained so for over six decades despite various changes in music distribution.

But Billboard is far from perfect. In 2023, the outlet's online publication, Billboard.com, caused a minor stir by publishing an article titled "Why Aren't More Pop Stars Being Born?" This article is more provocative than empirical, a confusingly unscientific effort from a magazine with ample data to ask and answer its own questions. Quotes referenced in this piece argue that music stardom is dead, blaming a cavalcade of usual suspects: TikTok, Spotify, the fall of radio, video games, record labels, and Taylor Swift.

I couldn't help but question the validity of these claims, especially if one were to fact-check this article with Billboard Hot 100 data. So today, we'll investigate whether music stardom is "dying," what might be driving this phenomenon, and whether tracking cultural celebrity has any greater meaning (or is just navel-gazing nonsense).

Are There Fewer Music Stars?

Stardom emerges from a concentration of cultural attention on a single artistic figure. For example, Chappell Roan is a music star because everyone is currently streaming and discussing her music—at least right now. She has captured a disproportionate share of listenership.

To quantify music celebrity, we'll deem someone a "star" if they've had three Billboard Top 40 hits within the past five years (on a rolling basis). To illustrate how this calculation works, we'll investigate ABBA's Billboard history. The Swedish supergroup had two hit songs in 1974 and one Top 40 tune the following year, meaning they earned "star" status in 1975 (according to our definition). ABBA remained a fixture of the Billboard Charts until their breakup in 1982, after which they gradually faded from the mainstream and lost their star status by 1984.

Admittedly, we could tinker with the parameters of this definition (like changing our three-hit threshold to five or ten), but that doesn't meaningfully alter the outcome of our analysis since we're tracking how this metric fluctuates over time.

When we chart the prevalence of music stardom since Billboard's inception, we find a surge of celebrity in the 1960s with the rise of rock, a slight dip in the 1970s, a rapid acceleration of this decline beginning in the early 1990s, and a very slight uptick in recent years likely stemming from the rise of streaming and (gasp) TikTok.

How could this be? Isn't declining music stardom the product of nefarious digital forces like Spotify, TikTok, and Taylor Swift? What happened in the 1990s that led to a drastic dip in Top 40 artists?

Ultimately, declining music celebrity can be attributed to various shifts in music distribution:

Record Label Consolidation: Many industry developments can be explained by mergers and acquisitions (a banal yet impactful economic force). This ever-repeating cycle of corporate development goes something like this:

An upstart label hits it big, or a formidable player stumbles.

A multinational whale like Warner Music or Sony gobbles up that player.

Rinse and repeat until there are no more acquisitions left to be had.

End State: Corporate consolidation yields a small set of labels taking bigger bets on a shrinking pool of mega-stars (i.e., Brittney Spears and NSYNC).

MTV: MTV was the music industry's most visible tastemaker in the 1980s and 1990s. For two decades, a disproportionate share of youth culture flowed through a single TV network. Over time, MTV became a cultural echo chamber capable of minting superstars, funneling air time toward a curated collection of music acts like Madonna, Nirvana, and Alanis Morissette.

Genre Fragmentation and the Internet: In the 1990s, new music categories like rap and hip-hop emerged, while rock splintered into various subgenres such as grunge and alternative. The internet allowed consumers to access and explore niche genres, making it harder for any one artist to achieve broad-based "superstar" status.

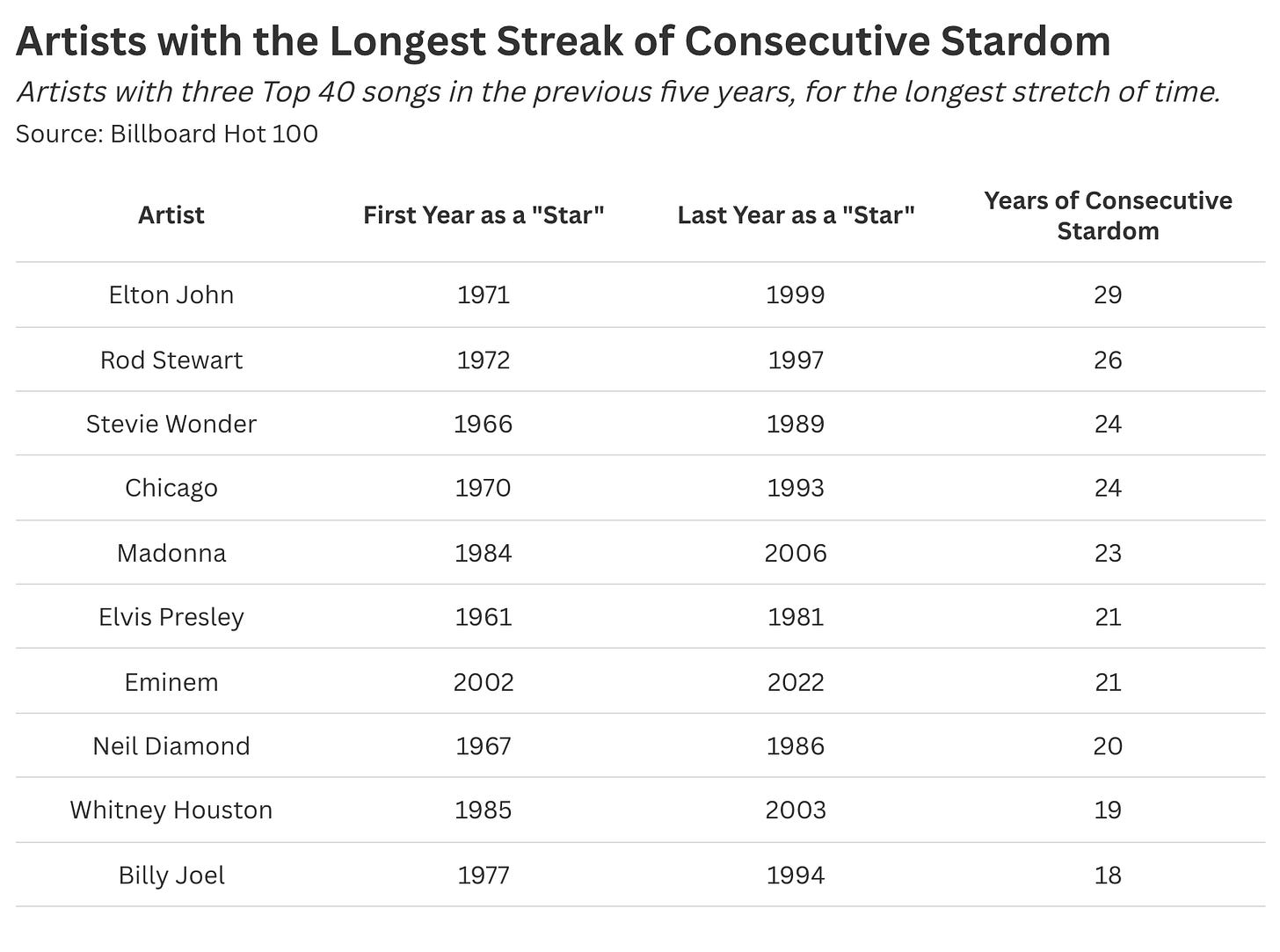

When we look at the artists with the longest consecutive run of music stardom, we find most acts predate the 1990s.

Billboard.com is correct, but only to a certain extent: music stardom is dying, though this phenomenon isn't a recent development. So, if pop celebrity began declining in the 1990s, what cultural forces stopped these declines in recent years? What's the state of the Billboard Charts in the 2020s?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

The (Slight) Rebirth of Music Stardom

In December of 2014, Billboard updated its chart methodology to include streaming data alongside traditional album sales. Under this new system, 1,500 song streams would equate to one album sale, a funky heuristic that has continually fluctuated over time.

At a high level, streaming's newfound dominance came at the expense of long-standing industry gatekeepers. MTV and other publications became increasingly irrelevant, and record labels lost their stranglehold over music distribution (now, anyone can publish music online).

As a result, popular taste would come to be defined by algorithms and playlists—new-fangled products of attention-harvesting streaming platforms. Changes in music distribution and consumption fostered an increasingly democratized industry, with more artists and songs making the Top 40 in a given year.

However, this uptick in trending songs and artists has not yielded a commensurate increase in music stardom (according to our first graphic). How is this possible? The answer is time.

Sure, the Billboard Hot 100 has greater song diversity, but these artists do not possess a similar hold over popular imagination. An artist's average tenure in the Top 40 has meaningfully decreased with Spotify and TikTok's ascendence.

Our cultural attentions have become like that of a goldfish. At this point, we can (once again) return to the Billboard.com article on music celebrity: this piece seemingly confuses declining stardom with decreasing attention spans.

Musicians like The Lumineers or Lorde can invade the zeitgeist and burn bright for a short period of time before mainstream culture moves on to the next big thing—kind of like a traveling circus (the type Billboard would cover circa 1895). The music industry has slightly more "stars" (as of late), but this stardom comes with an ever-shrinking half-life.

Final Thoughts: Consolidation or Democratization?

Why should anyone care about the idolization of commercial music acts? Said differently, do any of these facts and figures matter? Broadly speaking, there is nothing wrong with fewer music stars, given pop stardom is a bizarre construct in the first place. Nobody's life is materially improved when media outlets cover Taylor Swift's every move or fixate on Chappell Roan's tweets.

At the same time, the prevalence of music stardom (and other forms of stardom) serves as a reflection of cultural attention. People can only listen to so much music; there is a fixed set of collective listening capacity within a given year. How this proverbial "pie" of listening hours is divided among musicians shapes the emergence of monocultural figures (or lack thereof) and determines their staying power on the Billboard Charts.

If you care about this stuff (and I wouldn't blame you if you didn't), then the frequency of widely-known music acts presents you with a Rorschach test, where you might favor:

Consolidated Attention and Fewer Stars: Perhaps you miss the good old days of MTV and Brittney Spears when "stars were stars"—when rock groups could remain a fixture of popular culture for decades, like The Rolling Stones or Chicago. You weren't a cultural dinosaur because everyone listened to a smaller set of artists, and you didn't have to learn about some new-fangled music act every other week. Everybody loved Elton John, and it was a simpler time.

Democratized Distribution and More Stars: Why do record labels even exist in the first place? Why were MTV and a small cadre of industry executives the grand arbiters of music taste for so many years? Spotify and social media rid music of unnecessary gate-keeping. Anyone can go viral nowadays, even if that virality only lasts so long.

Every decade or so, the music industry undergoes a major paradigmatic shift in distribution. In the 1960s, fame was defined by radio airtime; today, celebrity can arise from a viral hook becoming the centerpiece of a TikTok dance challenge.

The drivers of music stardom are ever-changing, yet one thing remains certain: nothing lasts forever—not even Elton John or the vaunted bill posting industry.

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting and data journalism services!

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Isn't this just Econ 101 playing out in real time? We've gone from an oligopoly of MTV and record labels manufacturing scarcity to something approaching a perfect market where anyone can drop a track on Spotify.

Turns out when you remove the gatekeepers, the market satisfies a much wider spectrum of musical tastes instead of force-feeding us a few manufactured pop stars.

The top 100 is one of the first echo chambers: things are popular because they are deemed popular. As Derek Thompson pointed out (don't know how original source,and others have done the same) , Billboard changed its methodology in the '90s from store owners self-selecting stock they wanted to move to point of sales. The churn before then, in which there could be more stars, was artificially propped up. The increase in the last decade could be attributed to more flash in the pan popularity, or increasing options of new things.