How Video Podcasts Took Over Streaming: A Statistical Analysis

The rise of video podcasts, quantified.

Intro: Good Fun

I try to be a cool guy. When a cultural trend emerges, and I find myself on the outside, I generally let that knowledge roll off my shoulders.

If the kids are watching a convoluted movie about demon-hunting K-pop singers, then I’ll watch this film and tell people that I, too, enjoyed it.

If the numbers “6” and “7” can no longer be said in the same sentence, I will chuckle and applaud the youth on their irreverent sense of humor.

If teens are eating Tide Pods, I will accept this as good, clean (extremely self-destructive and borderline lethal) American Fun.

But my coolness has its limits. The other day, I heard a statistic that no amount of mental gymnastics could make sense of: apparently, the most common platform for podcast consumption is YouTube. If you’re like me, then your immediate reaction might be something along the lines of “why surely that makes no sense—YouTube is a video platform!” Well, the simple answer to this quandary is that people are consuming their audio content by way of video.

According to my rigid worldview, podcasts were created by Steve Jobs as a mindless auditory experience that might complement household chores or a walk to the grocery store. I cannot consume a podcast with my eyes because then I would be unable to wash the dishes or clean my cat’s litter box. Apparently, I am old-fashioned, tied to a bygone vision of what podcasts should be.

Stranger still, the rise of video podcasting has reshaped the entertainment landscape, prompting platforms like Netflix and Spotify to embrace this hybrid format. Once again, tech platforms are pivoting to video, taking content built for ears and retrofitting it with a visual dimension. My decidedly uncool brain cannot make sense of this trend—which means a full-fledged investigation is required.

So today, we’ll explore the rise of video podcasts, their growing influence on entertainment’s streaming wars, and the reasons why this hybrid format resonates.

The Rise of Video Podcasts

For the past 20 years, I lived my life believing that Steve Jobs invented podcasts. I assumed somewhere between producing Toy Story and unveiling the U2-themed iPod, he took a ten-minute break during which he casually disrupted talk radio.

In reality, podcasting predates the iPod entirely, emerging in the early 2000s as independent developers began experimenting with RSS feeds and audio enclosures. Apple’s role came later, in 2005, when it standardized and mainstreamed the format by integrating it directly into the iTunes storefront.

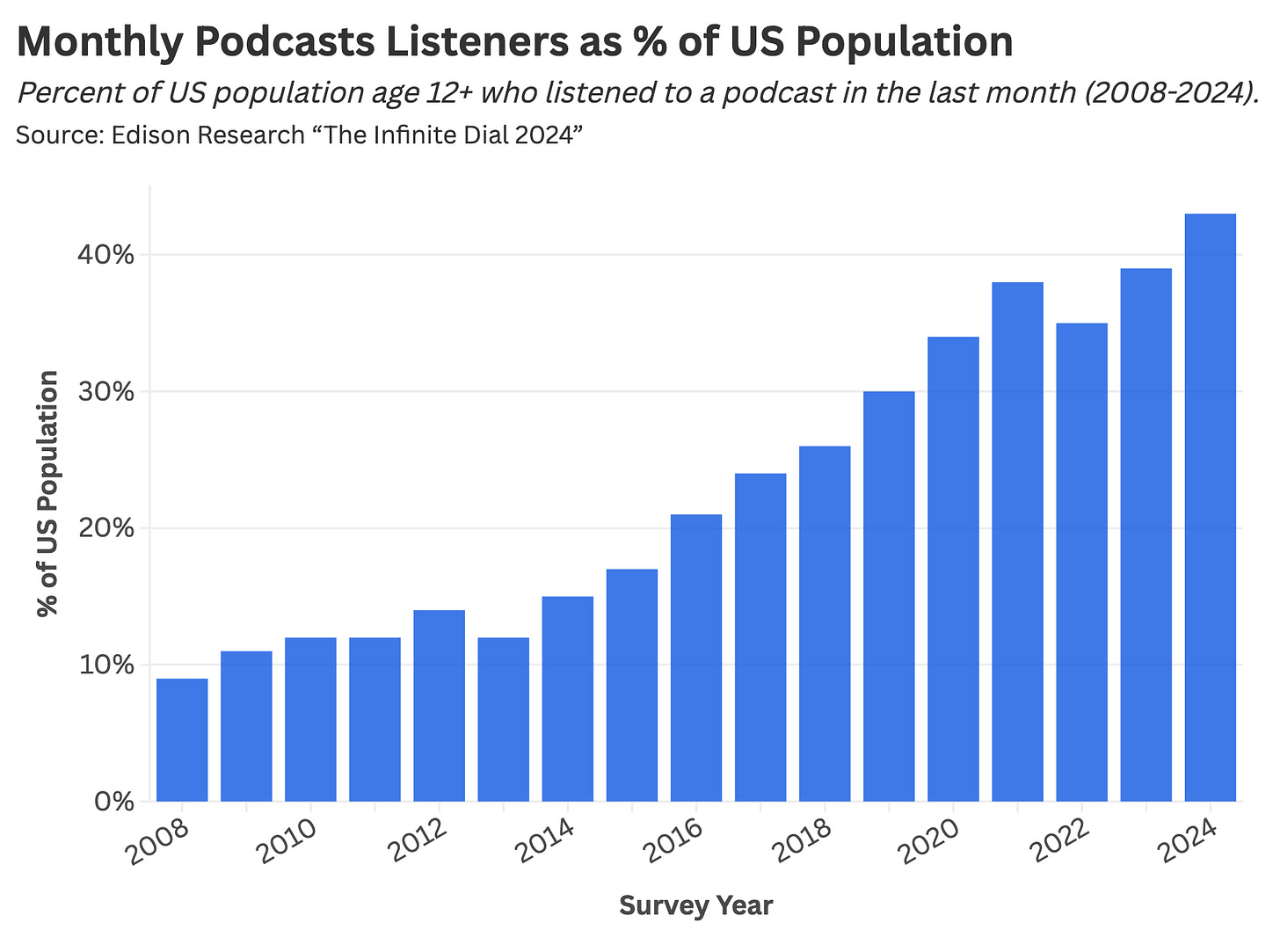

Since the late 2000s, podcast adoption has steadily increased, with platforms like Spotify and Amazon making the format a core part of their offering. As of late 2024, more than 40% of U.S. consumers listen (and watch) podcasts monthly.

Spotify, in particular, has aggressively embraced the format in its quest to dominate “share of ear,” giving podcasts prominent placement across its homepage and search experience. Against this backdrop, reports of YouTube’s growing dominance in audio were especially alarming for the Swedish streaming giant.

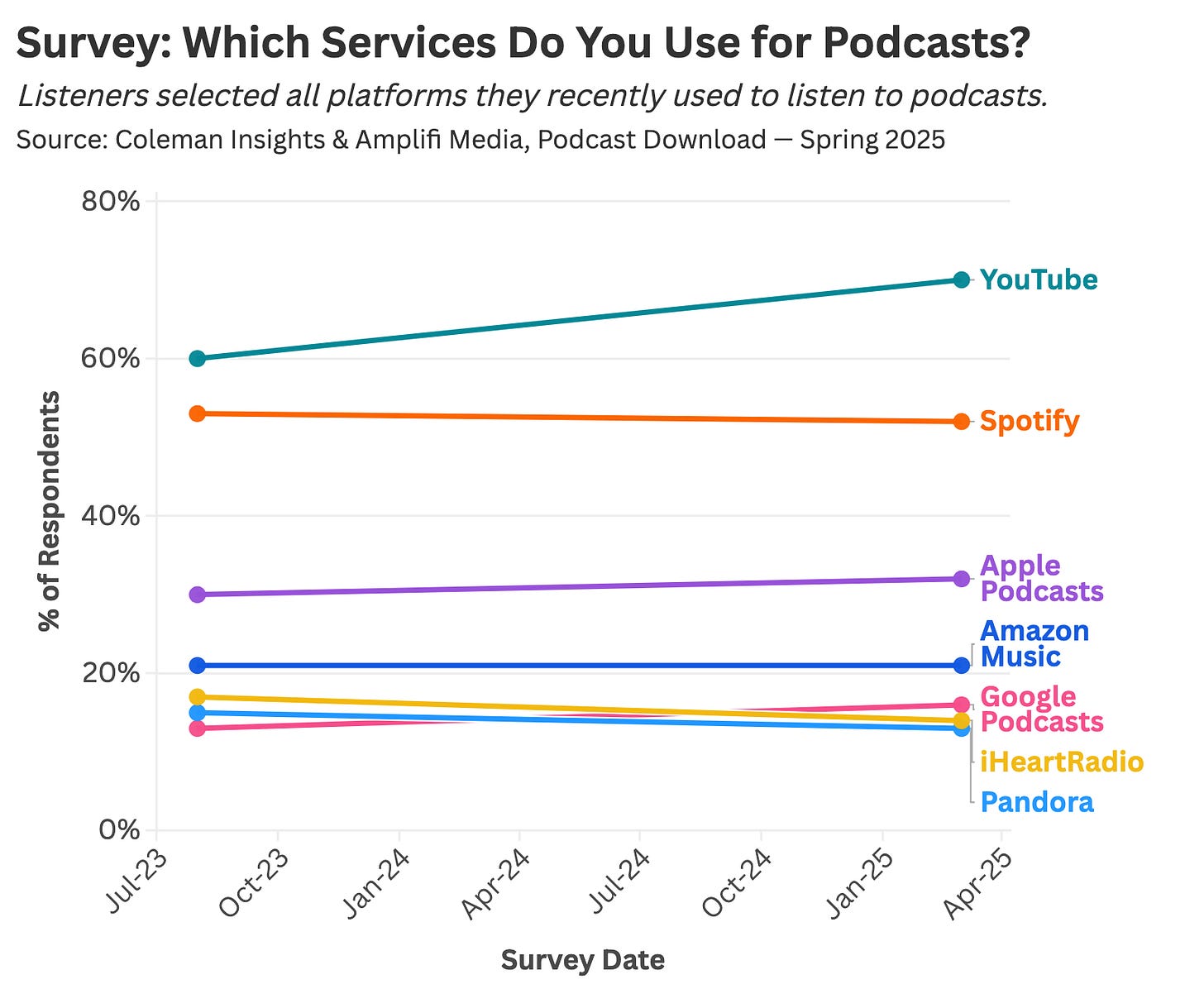

While the exact figures vary by survey, the conclusion is consistent: YouTube has quietly become the largest destination for podcast listenership.

This revelation likely set off alarm bells at Spotify HQ, triggering a series of inane “war room” meetings where employees, united by a shared fear of stock option depreciation, brainstormed ways to elevate podcasts and counter YouTube’s momentum.

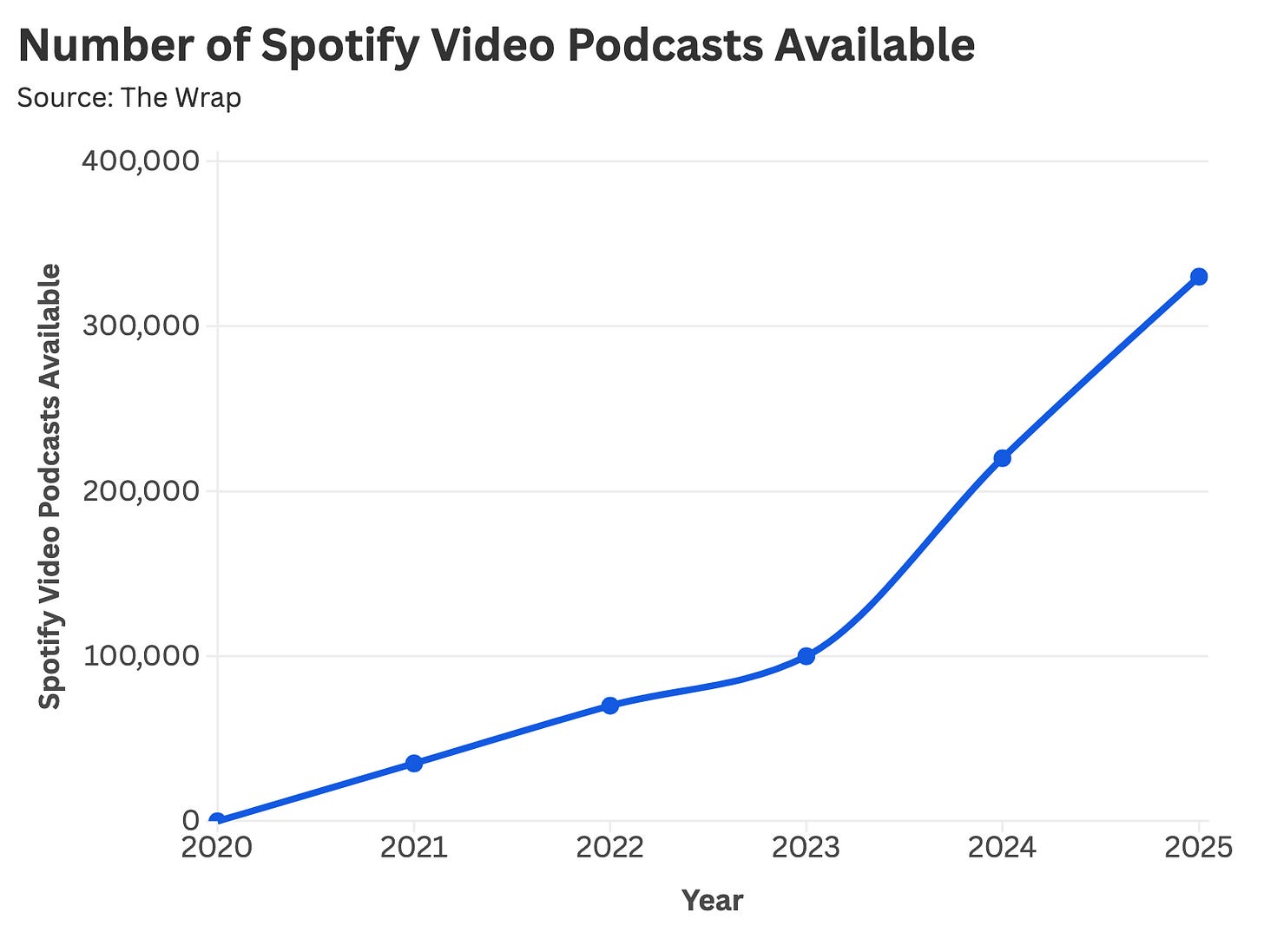

The most obvious response to YouTube’s advantage was also the simplest: pivot to video. And pivot to video they did. Over the last two years, Spotify has more than tripled the number of video podcasts available on its platform.

And here is where things get personal. Since 2019, Spotify has been my go-to destination for podcasts, especially for shows produced by The Ringer, which was acquired by the streamer in 2022 (and has since become its content creation arm). Spotify’s embrace of video means that all my favorite shows have added a visual dimension, which has led to unintended consequences:

Begrudging Hosts: The hosts of my favorite podcasts consistently complain about having to be on camera. This happens enough to warrant a brief mention.

Increased Content Load Time: More importantly, every podcast takes longer to load because the platform defaults to video. Spotify is certainly aware of this trade-off; it has simply decided that competing with YouTube outweighs any degradation to consumer experience. Given Spotify’s famously skilled data science team, this added latency has definitely been quantified down to the millisecond. If any Spotify data scientist with firsthand knowledge of this UX regression is feeling whistleblower-curious, my inbox is open—together, we can fix this extremely low-stakes problem in the name of content accessibility!

Every time I load a podcast, and it takes two to three seconds longer than it should, I’m left with the same beguiling question: Who asked for this? Unfortunate for me, the answer to this query is: A lot of people.

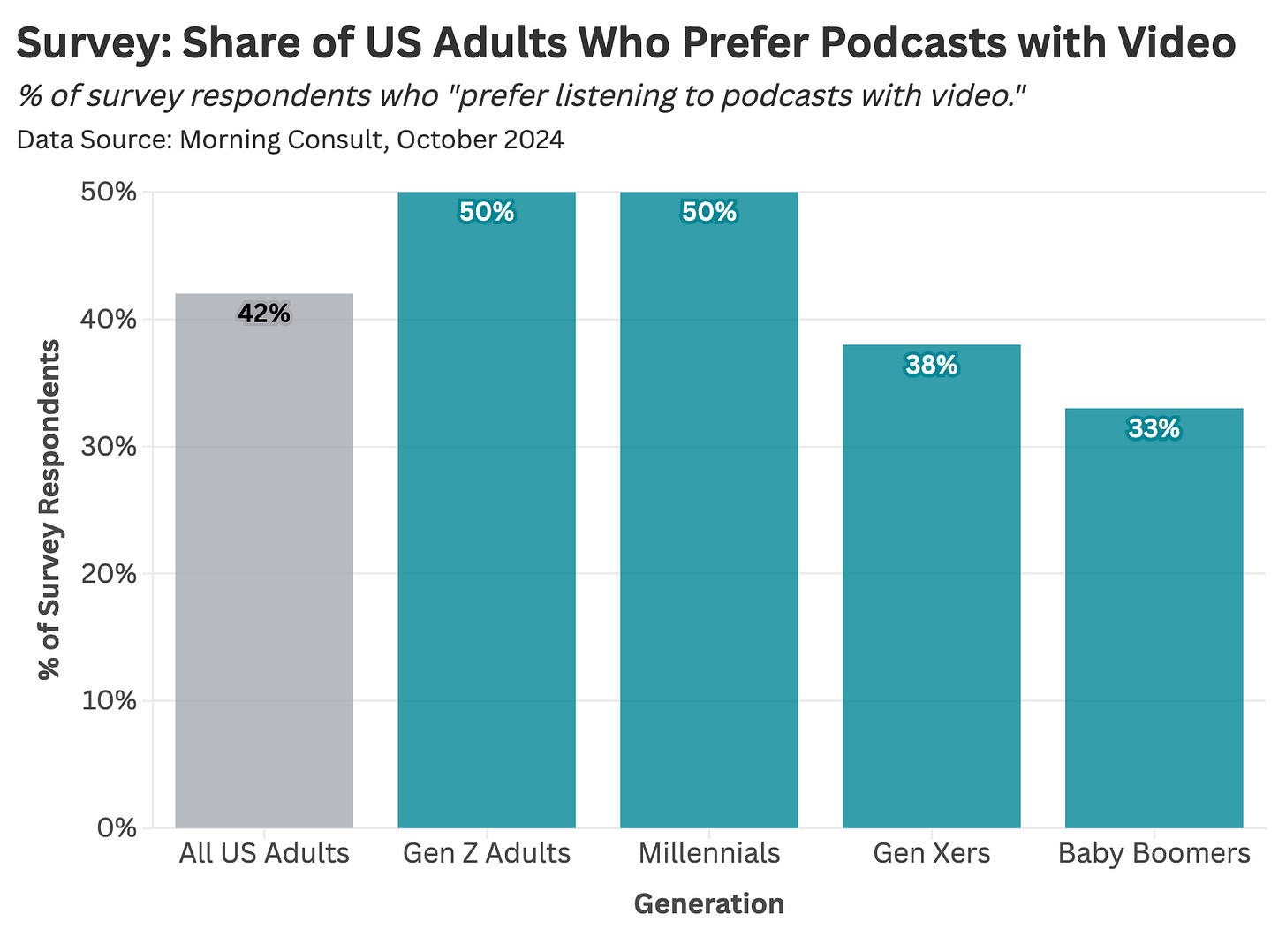

According to polling from The Morning Consult, nearly 50% of millennials and Gen Z adults prefer listening to podcasts that have video (and I’m sure this number will increase with each passing year).

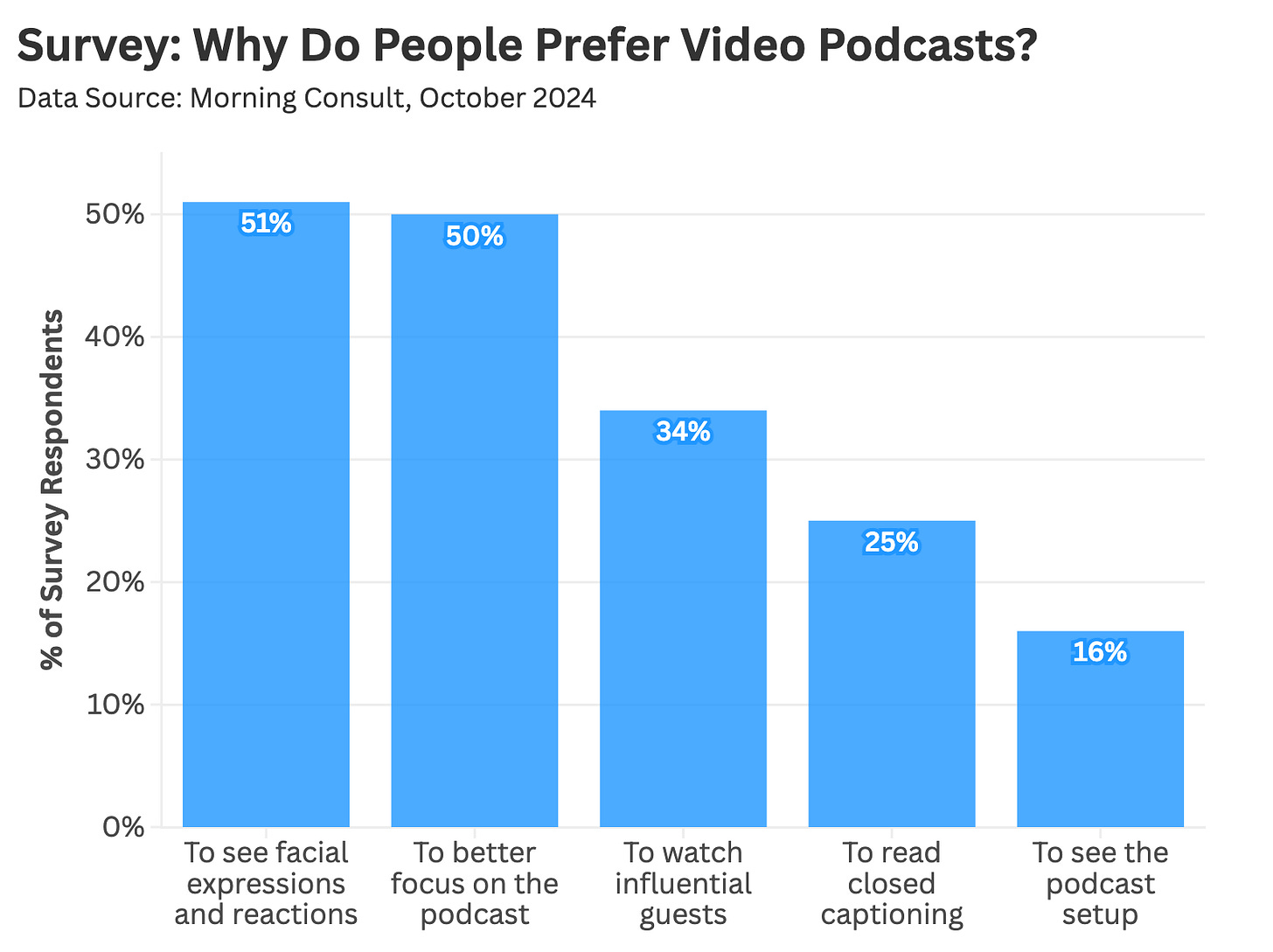

Inevitably, my next question is: why? Why do people want to watch other people sit still and talk? The rationale, it turns out, is ostensibly wholesome. When asked why they prefer video podcasts, survey respondents cited a desire to see facial expressions and a need to better focus on the content itself.

Perhaps this preference reflects a generational divide—a fault line in how people allocate attention to audio programming. I long assumed podcasts were designed for multitasking; clearly, many listeners disagree. So much ink is spilled on shrinking attention spans, yet the rise of video podcasts could be read as a sincere shift in the opposite direction—or at least that’s how I’d like to interpret the data.

At a macro level, the mass adoption of video podcasting is driven by two mutually reinforcing phenomena:

Many consumers prefer active audio consumption over passive engagement.

This burgeoning audio-visual hybrid is uniquely effective at sustaining attention, prompting major tech platforms—which make money by alleviating boredom—to gravitate toward this format.

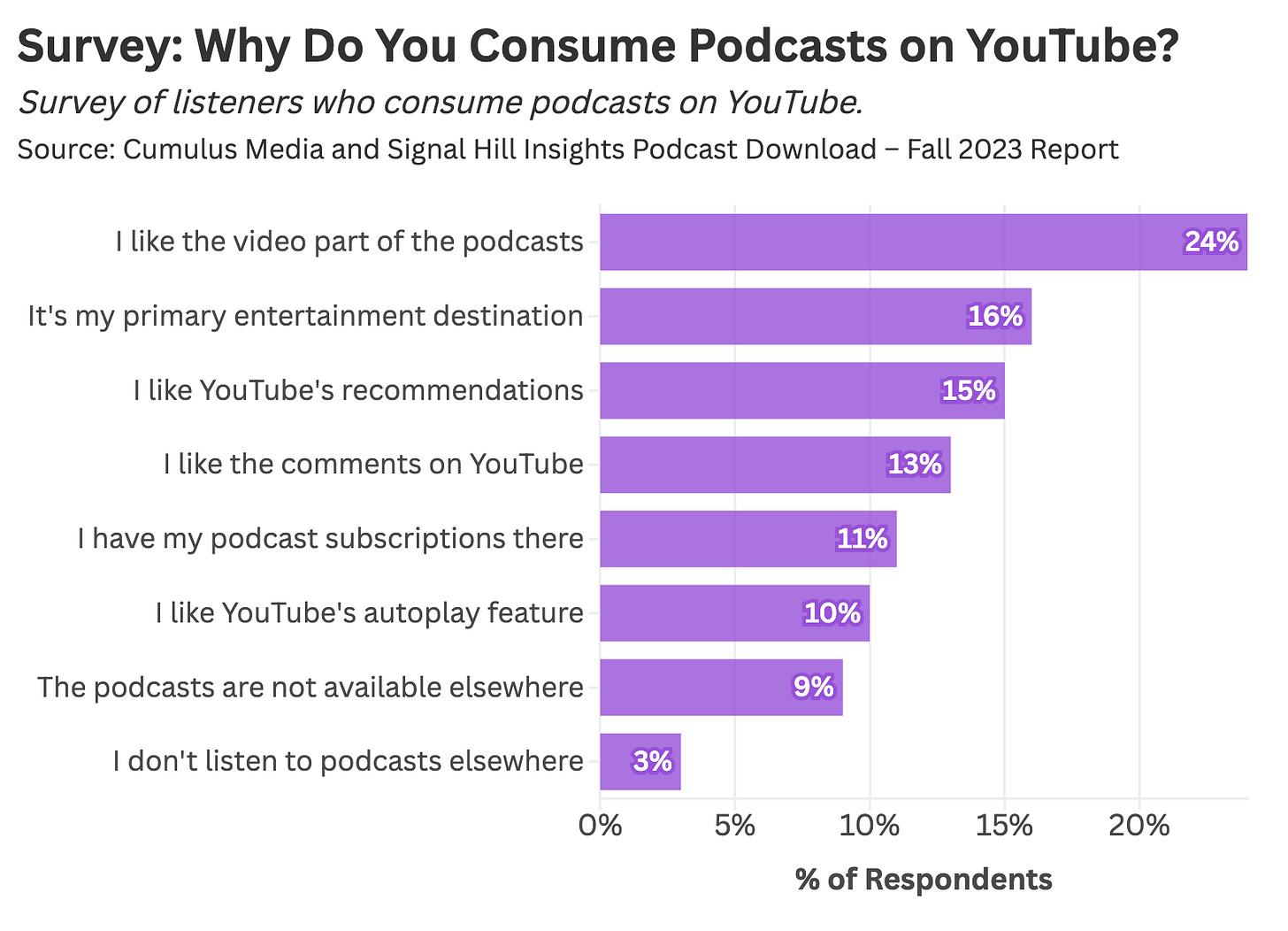

When YouTube podcast consumers were asked why the platform is their default for episode consumption, they cited a preference for video, long-standing viewing habits tied to YouTube, and the appeal of the site’s discovery and social features, such as recommendations and comments.

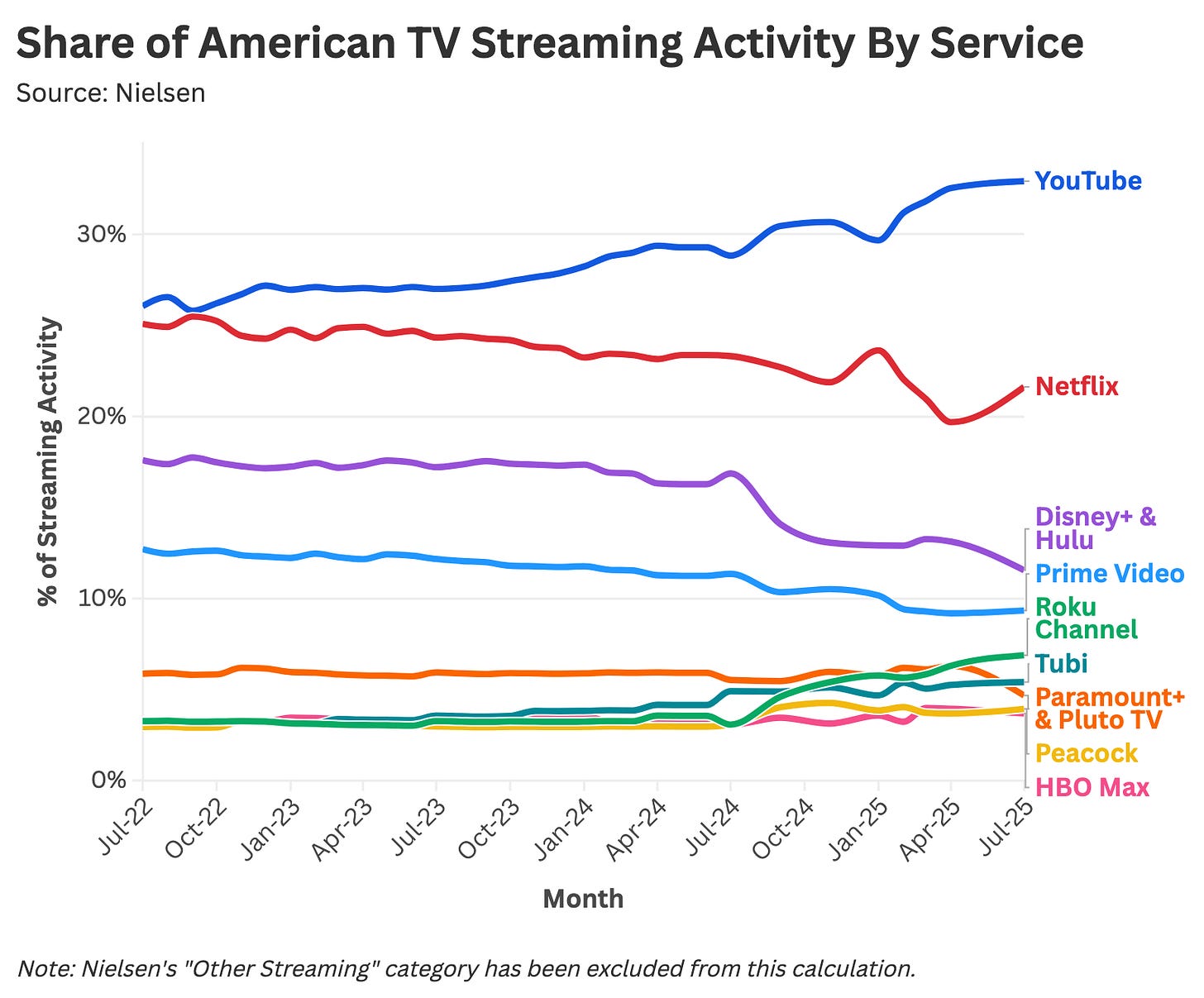

YouTube’s sheer dynamism has turned the platform into a one-stop shop for content of every kind. When I first watched videos like “Charlie Bit Me” or “Double Rainbow,” it was impossible to imagine that this same website would one day subsume—and dominate—nearly every form of digital entertainment. Yet here we are: YouTube is winning the video and audio streaming wars.

According to Nielsen, YouTube is now the most-consumed streaming service on television, surpassing Netflix and Disney+ by a wide margin.

Fueled by Saturday Night Live clips, music videos, a jingle about a chimpanzee riding on a Segway, Hot Ones, and virtually every other form of human expression the internet can produce, the platform has become everything for everyone—which includes podcast consumption.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: The Great Content Convergence

Perhaps the most striking consequence of YouTube’s dominance is the rapid convergence of audio and visual content across major tech platforms. Spotify has gone all-in on video; Netflix is actively courting podcasters to its platform (including outfits like The Ringer); and Amazon is locking up well-known audio shows with exclusivity deals worth tens of millions of dollars.

Which brings us to Substack. Substack launched in 2017, and at the risk of being overly reductive, has marketed itself as a corrective to journalism’s decline. That framing has been effective: the platform has successfully pulled high-profile writers away from legacy publications into a direct-to-reader model.

It’s at this point that I should mention that I host my newsletter on Substack, and while I have some gripes about how the platform has evolved, my view of the company is largely positive. So why bring Substack into a discussion about video podcasting? Because I find it instructive that, over time, the platform has come to resemble nearly every other social network, while insisting on its commitment to preserving journalism.

In early 2025, Substack began encouraging writers to “go live,” offering a video podcast hybrid distributed through subscriptions and the platform’s newsfeed. I don’t have a strong opinion on whether this was the optimal strategy or what it means for Substack’s founding ethos. What interests me is the incentive structure that made this decision inevitable.

Despite the company’s stated—and, I think, sincere—commitment to journalism, Substack remains a venture-backed business. It has raised tens of millions of dollars from Silicon Valley firms, most notably Andreessen Horowitz, which is one of the most successful investors of the past two decades.

The unfortunate reality is that Andreessen Horowitz doesn’t back a media startup because it might “save journalism.” It invests because it believes the company could become one of the five or six monolithic platforms that monopolize attention across a variety of media formats. This explains why Substack has rolled out a Twitter-like feed, introduced live video, and is reportedly experimenting with advertising. Increased investment has led Substack to have the same incentives as Netflix and YouTube and Spotify, which means its design will increasingly resemble theirs.

The end state is convergence: as platforms compete to capture attention, they cluster around the same four or five content formats, with video podcasts serving as the latest addition. Today it’s a pivot to video; tomorrow, who knows—perhaps everyone will begin cloning LinkedIn games.

So if you’re unlike me and genuinely enjoy video podcasts, congratulations—you’re about to get a lot more of them. And if you haven’t embraced the format, consider this fair warning: the coming flood of audio-turned-video will test the boundaries of your coolness.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 24,100 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

Fascinating observations and well-written as always; Thank you! I suffer from a different affliction - impatience. Video Podcasts take too long to get to the point of what they’re trying to communicate. I would rather read a transcript, an activity that consumes 10 minutes (or less) of my time, than sit through 25 minutes of a video podcast. TIME is our most precious commodity, and if I cannot multitask through an audio-podcast, then I will not consume at all.

Thanks, Daniel. You've officially made me feel old with this post. I've always considered podcasts as the media for long walks across camps or the drive home. The last thing I need is another screen in front of my face.