How Romance, Romantasy, and “Smut” Took Over Publishing and Entertainment: A Statistical Analysis

How romance novels are reshaping the book business—and Hollywood.

Intro: Similarity by Happenstance

Can you claim plagiarism in a genre that thrives on familiarity? A 2022 lawsuit put this contradiction to the test, forcing courts to define the boundaries of unlawful copying within modern romance literature.

The case centered on an Anchorage author who filed a copyright-infringement lawsuit against best-selling writer Tracy Wolff, whose Crave series has sold more than 3.5M copies. The complaint pointed to a shared Alaskan setting, a supernatural heroine with identical powers, multiple overlapping plot elements, and the plaintiff’s unpublished manuscript being shared with Wolff’s publisher—details that, at first glance, make the case read like a textbook example of plagiarism.

And here is where things get wacky: the defense argued that the novels’ resemblance was not evidence of copying but of coincidence, an inevitable byproduct of a commercially oversaturated genre built around a narrow set of well-worn tropes. Wolff’s attorneys asserted that in a crowded market, two independently written romance novels can (and did) arrive at similar stories precisely because the genre rewards predictability.

As of this writing, the lawsuit is headed for trial, marking a strange inflection point for the publishing industry, which is increasingly reliant on romance’s explosive growth.

Once considered niche, romance novels now account for roughly 20% of annual book sales, with their influence no longer confined to book clubs and die-hard Austenites (a nickname for Jane Austen fans). In recent years, the genre has spilled into mainstream culture, fueling a steady pipeline of streaming and big screen adaptations (Red, White & Royal Blue, Heated Rivalry, It Ends With Us, and beyond).

So today, we’ll explore the rise of romance novels, how the genre is reshaping the publishing industry and the word “smut,” and why the genre’s grip on popular culture is stronger than ever.

How Romance, Romantasy, and “Smut” Took Over Publishing—and Hollywood

A new bookstore opened down the street from my house a few months ago. Eager to support a local business, I wandered in and began scanning the shelves. After two minutes of unfamiliarity with the store’s titles—many of them romance or romantasy—I asked the clerk where I might find a copy of [insert the name of a well-known cerebral novel I will never read, for now let’s just say it was The Sun Also Rises]. To which the store manager responded, “We don’t do that.” She then launched into a well-choreographed—and clearly oft-delivered—explanation of the store’s schtick. Their inventory, she explained, was driven by influencer recommendations and community-centric book clubs.

Even today, I don’t understand how this place pays its rent. My fundamental confusion is not the store’s focus on community—which, as best I could tell, skewed female—but that a bookshop could afford to be niche in this day and age. Can a bookstore thrive while selling a narrow subset of contemporary favorites? The answer is yes—provided that subset includes romance.

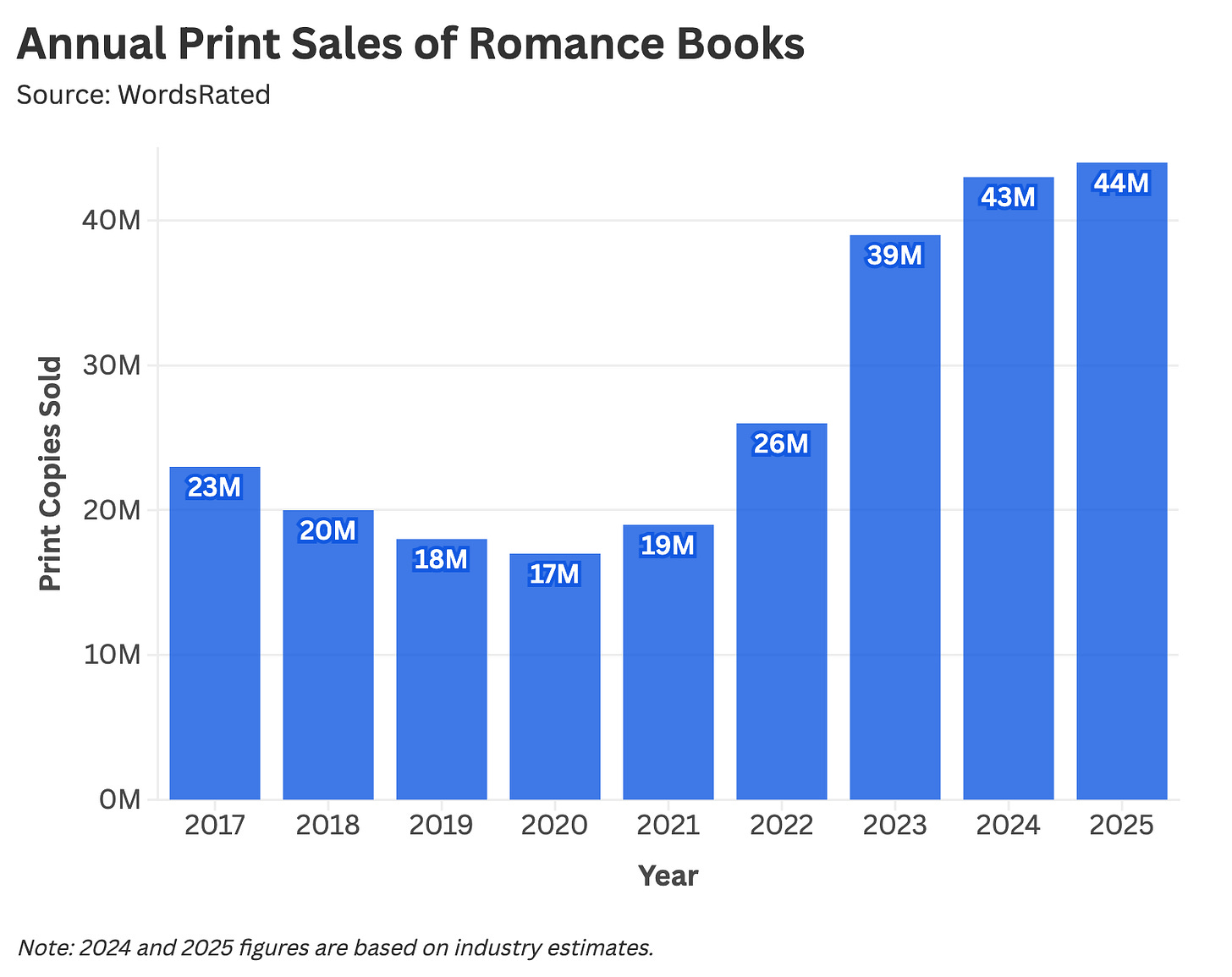

The genre has exploded in the post-pandemic era, propelled by TikTok’s #BookTok community. In print alone, romance novels have more than doubled their sales over the past five years—an outcome roughly equivalent to DVDs staging a cultural comeback.

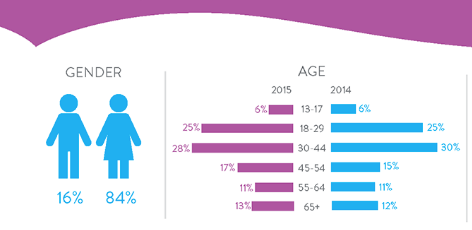

The readership of these novels is overwhelmingly female—and if that comes as news to you, then that’s somewhat impressive on your part. According to a Nielsen study on the romance format, 84% of readers are women, with more than half falling between the ages of 18 and 44.

This gender imbalance underlies a persistent media tendency to trivialize romance literature. The genre is rarely covered favorably—treated less as a durable cultural force, and more like an inexplicable fad or collective delusion. Meanwhile, I can “manage” a fantasy football team composed of athletes I will never meet, and this behavior is widely endorsed.

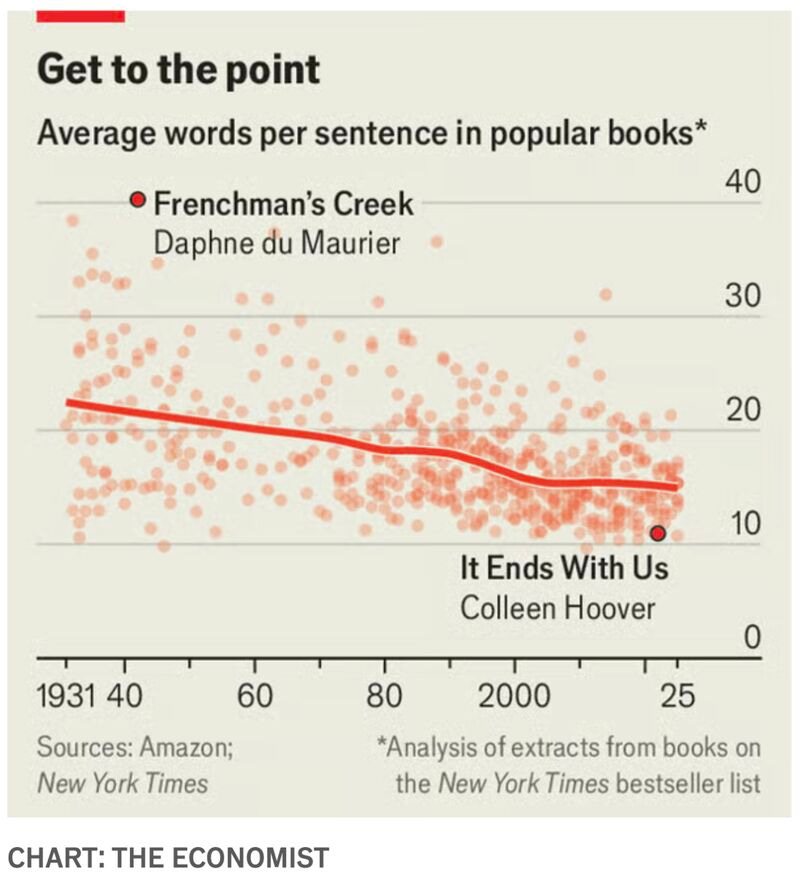

For example, Colleen Hoover—the genre’s most popular author—has increasingly become shorthand for unserious fiction, replacing older stand-ins like Tom Clancy or the term “airport novel.” You can see this framing at work in a recent Economist graphic on declining sentence length (where Hoover signifies the range’s lower end).

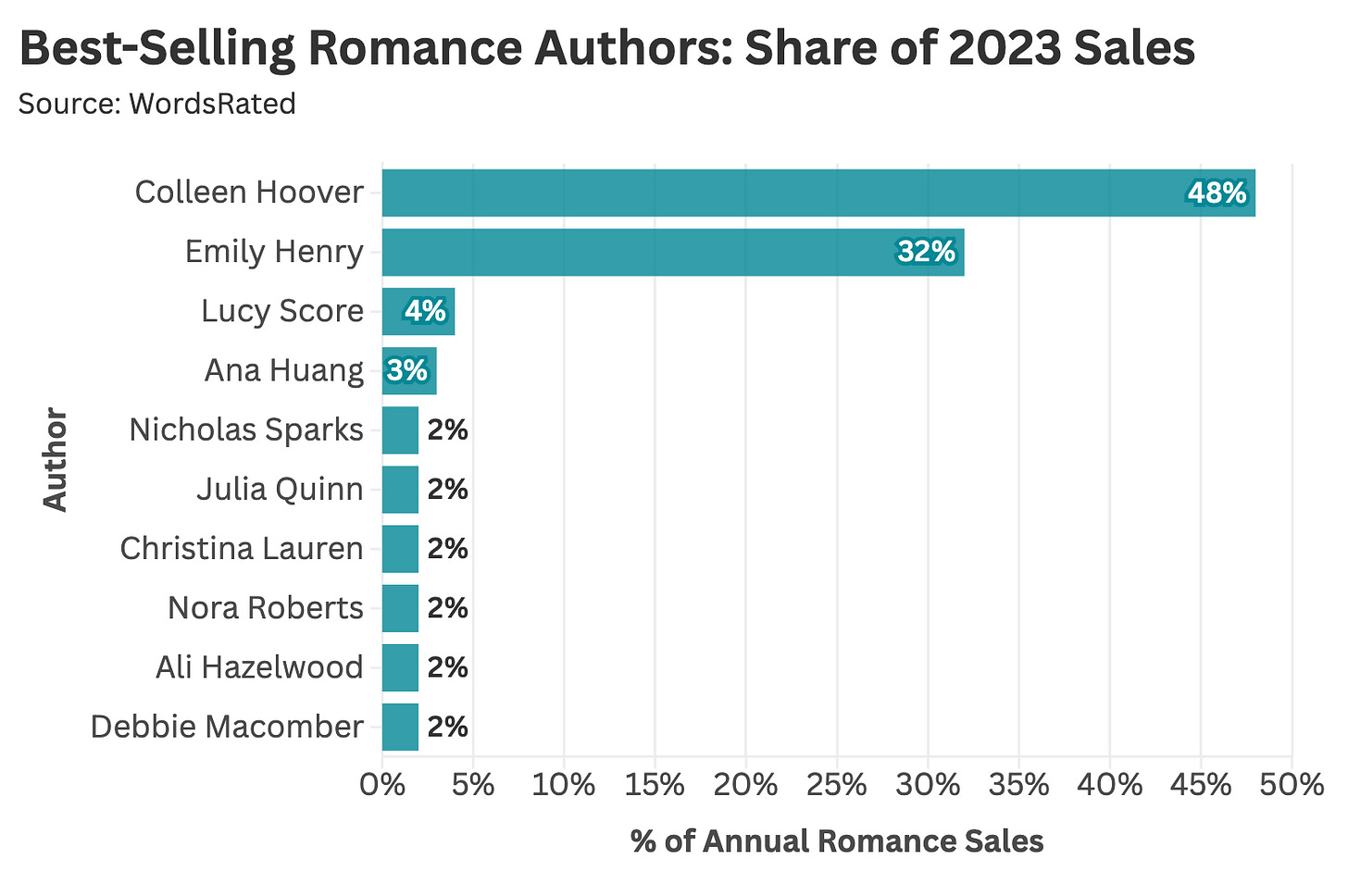

And if you’re somehow unfamiliar with the name Colleen Hoover, prepare to learn about a phenomenon that’s been hiding in plain sight—like the arrow in the FedEx logo. Despite the flood of novels into an already crowded market, Hoover alone accounts for nearly half of all romance fiction sales.

Hoover’s tremendous popularity has produced two big-screen adaptations in 14 months—It Ends With Us and Regretting You—with two more slated for release this year (Verity and Reminder of You).

That success has sparked a broader wave of film and television projects based on popular romance novels, including My Oxford Year, People We Meet on Vacation, and, of course, Heated Rivalry. Industry coverage has framed these adaptations as an inflection point for the genre’s cultural recognition. Yet there’s nothing especially new about romance’s appeal.

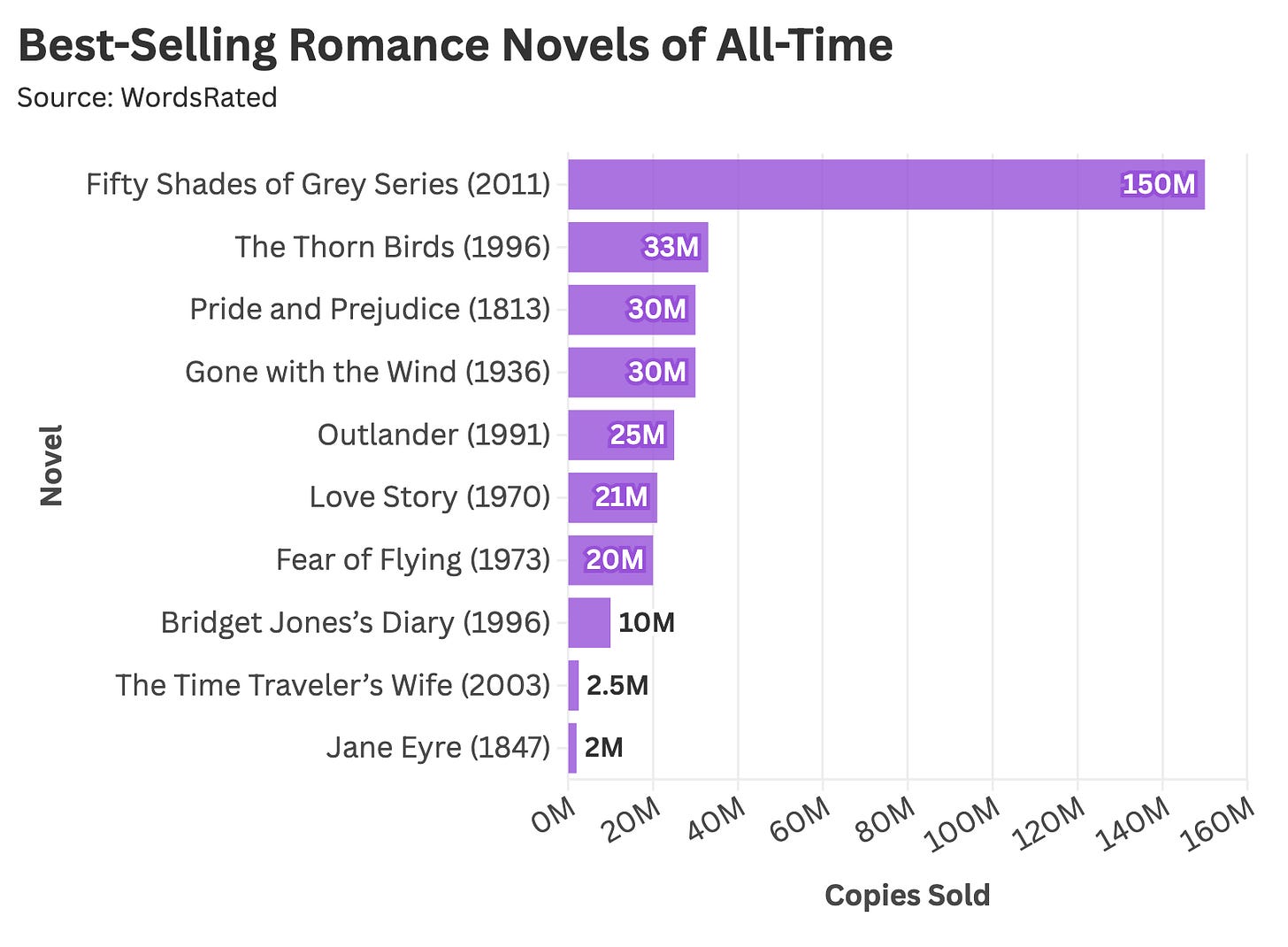

For decades, best-selling romance novels have reliably translated into film and television series—a pattern evident among the genre’s ten best-selling books.

So what feels new about this recent wave of best-selling series and adaptations? Ultimately, the modern incarnation of romance books is the product of three cultural shifts:

BookTok and Book Clubs: When TikTok first came on the scene, I assumed its rapid growth would be another blow to reading—but that wasn’t entirely true. There is now a thriving community of literary influencers recommending novels on social media, leading people to label every popular book they do not know as “a BookTok thing.” This community is not exclusively based around romance, but the genre has been one of its biggest beneficiaries.

The Blending of Romance and Fantasy: Twilight forever changed the genre by successfully blending romance and fantasy elements for pop sensibilities. In recent years, Twilight’s descendants have been grouped into a subgenre of their own: romantasy. There are many flavors of romantasy: fae romantasy (fairies and elves), dark romantasy (disturbing content and horror elements), paranormal/monster romantasy (vampires and werewolves), enemies-to-lovers romantasy (self-explanatory), and these are but the tip of the iceberg. If you cannot wrap your mind around these stories, be forewarned: there will probably be 20 film and television adaptations of romantasy novels in the next few years.

Graphic Sex: Once again, Twilight casts a long shadow over the genre, as fan fiction inspired by the series produced the most commercially consequential romance title of the past two decades. I’m of course talking about Fifty Shades of Grey, the best-selling romance novel of all time—by a wide margin. Much of the book’s initial reputation centered on its graphic sex scenes and depictions of BDSM. The unprecedented success of the Fifty Shades series, coupled with a broader cultural tolerance for explicit sexual content in literature, helped usher risqué material into the mainstream.

While these dynamics do not define modern romance in its entirety, many best-selling series exhibit some or all of these traits. As the genre has evolved and expanded, imitation has also accelerated, with writers rapidly adopting the structures and tropes of earlier commercial hits.

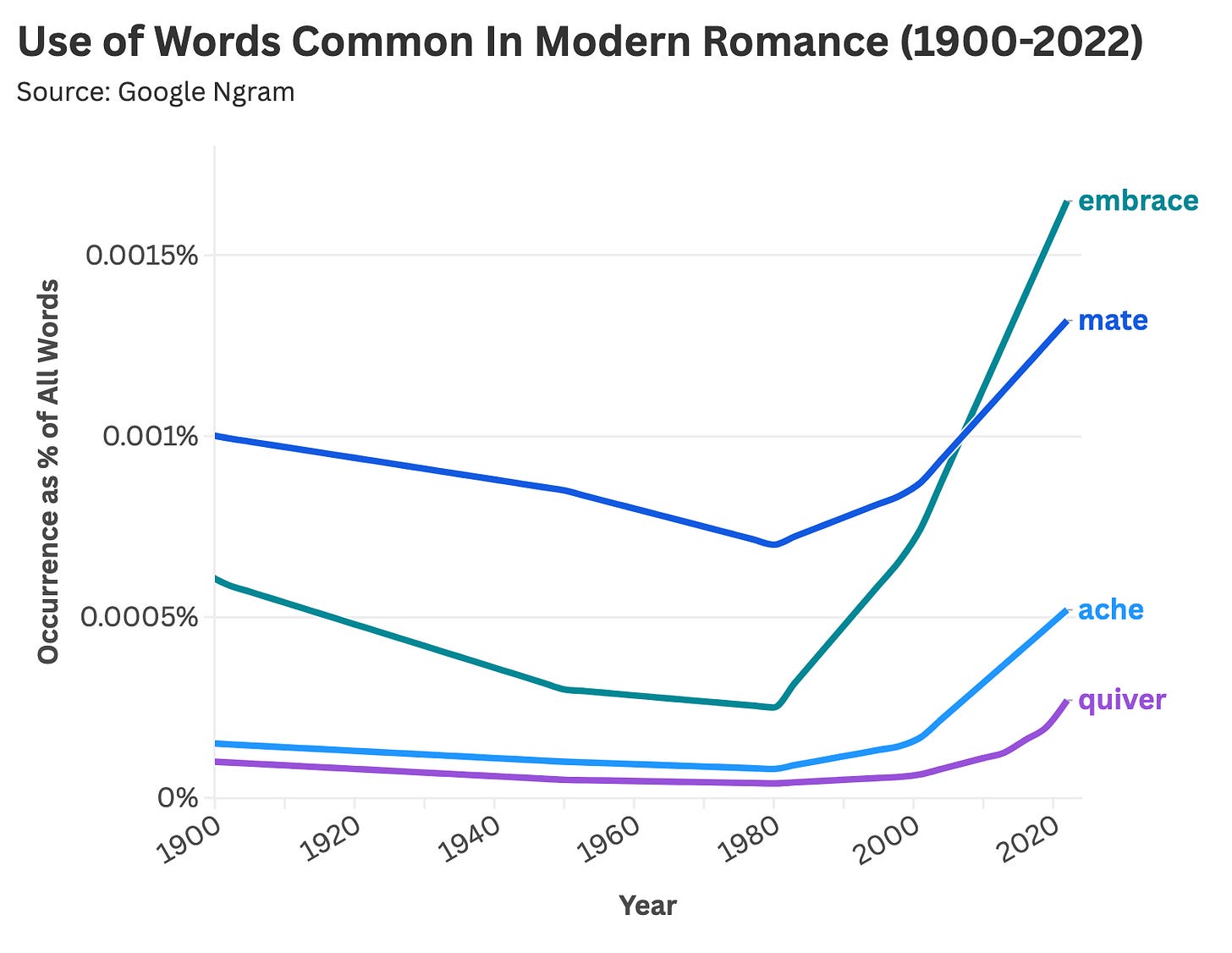

Take, for example, the vocabulary used to depict sex in novels. Over the past two decades, words like “quiver,” “ache,” “mate,” and “embrace” have become more prevalent in English literature as writers increasingly rely on a shared lexicon of sexually charged language to convey desire.

And it’s at this point that we arrive at “smut,” a reductive and surprisingly endearing label for romance novels that depict sex (often lots of it).

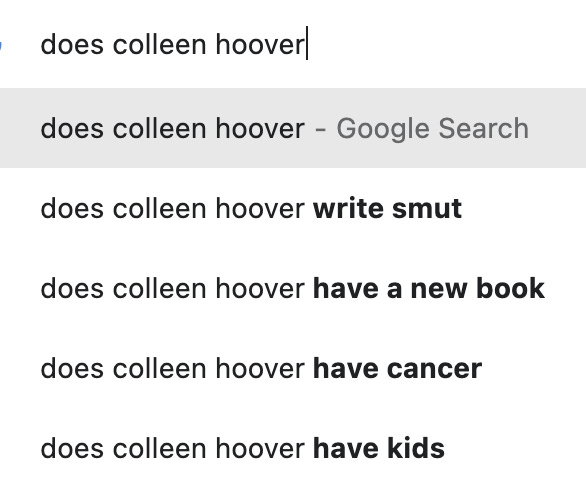

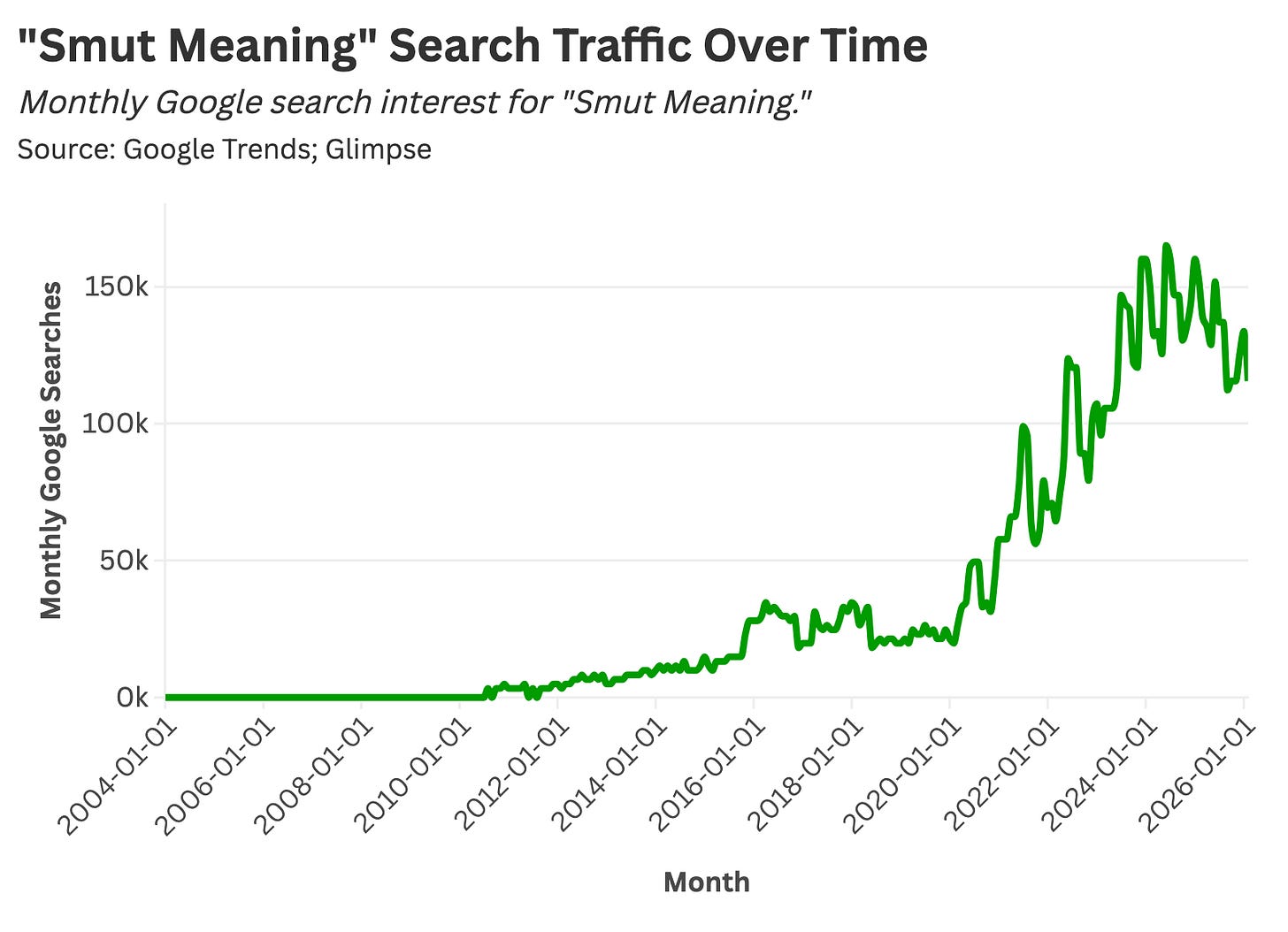

Before researching this piece, I’d heard the word “smut” used in reference to romance novels and assumed it was dismissive shorthand meant to undercut the genre’s popularity. Then I went to fact-check a Colleen Hoover statistic and was met with this auto-complete result.

I am not alone in my curiosity. Nearly 200,000 people per month are attempting to unpack what “smut” means in relation to this emergent wave of stories.

For those unfamiliar: “smut” is a tongue-in-cheek term embraced by romance readers to describe stories with explicit emphasis on sexual content. The moniker becomes even more playful when combined with romance subgenres. There’s fae smut (fairy romance with an erotic tilt), werewolf smut, hockey smut (yes, that’s Heated Rivalry), and countless other micro-categories that guide readers to their preferred story format. Once a word meant to describe soil-feeding fungi—smut has been reclaimed as a term of endearment.

If the success of Heated Rivalry and Fifty Shades proves anything, it’s that audiences have a healthy appetite for smut of all kinds. The inevitable follow-up question is what happens when smut goes mainstream.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: The Superhero Fatigue Blueprint

The first Comic-Con—then called the Golden State Comic-Minicon—took place in 1970 and drew roughly 200 attendees. The event was squarely focused on superhero comics from publishers like Marvel and DC, with programming designed for creators and devoted collectors. And while that small group of attendees may have hoped their community would grow, few could have imagined what the event would become—or how they might lose control of their own subculture.

Fast-forward to 2019, when Comic-Con was forced to cap attendance at 135,000 after the San Diego Convention Center reached its capacity limits. Over the course of five decades, comics have evolved from a dedicated niche into the entertainment industry’s most valuable source material, powering blockbuster films and streaming franchises. In recent years, however, Marvel’s cultural dominance has begun to waver, undercut by the genre’s full absorption into the mainstream and subsequent commercial fatigue. As superhero films grew, they began courting the superhero-agnostic, myself included, and exhaustively mined their source material until the well ran dry.

In 2018, I watched Avengers: Infinity War and—after decades of superhero avoidance—became invested in Marvel’s Cinematic Universe (MCU). The film’s cliffhanger left me, and millions of others, excited to see how the saga would end. In hindsight, my fledgling interest in the MCU might have been an omen for the franchise: if these stories had finally reached a laggard like me, how much longer could they sustain their cultural dominance? Said differently, what happens to a thriving subculture when it’s been fully absorbed (and co-opted) by the mainstream?

This past year, I was struck by a similar sensation while watching—and thoroughly enjoying—Heated Rivalry. Here again was an adaptation of a beloved series drawn from source material with a devoted fanbase that had previously existed within its own silo (hockey smut!). Between the show’s success and the blockbuster performance of recent Colleen Hoover adaptations, it’s easy to see where the romance genre is headed: there will be an inevitable gold rush to capitalize on its popularity, followed—just as predictably—by commercial exhaustion and inevitable downstream consequences for the genre’s source material.

Like comic books, romance novels are hardly new. Many of the genre’s most popular works date back to the 19th century, including Wuthering Heights, which is set to receive a big-screen adaptation in the coming weeks. What is new is the genre’s mainstream ascension, driven by a series of sociocultural shifts that have pushed romance books far beyond their traditional audience. For anyone familiar with the culture industry’s cycles of discovery, overexposure, and eventual discard, this pattern is all too familiar.

Which brings us back to the earlier case of Alaskan-witch-romantasy copyright infringement. What initially reads as a farcical tale of imitation is, in fact, another signal of commercial saturation: a market so crowded that “unoriginal by accident” has become a plausible legal defense, with the genre’s overabundance weaponized in court.

There is no shortage of demand for romance, romantasy, and smut of all mystical creatures and professions. Whether the industry that produces and adapts these products will allow these stories to thrive remains an open question.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

*Note: For best results, open this link in a web browser while logged in to your Substack account.

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 24,300 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

Calling Pride and Prejudice a "Romance Novel," is like calling Crime and Punishment a "Crime Novel."

This isn't a completely new phenomenon. I happened to recently be reading an old post by the SF writer Charlie Stross about the economics of writing from 2010: https://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/2010/04/cmap-8-lifestyle-or-job.html

In the comments he says, "Figures from memory: SF/F accounts for about 7% of fiction sales in the US market, while Mainstream is around 11%; crime/thrillers are around 16%, and romance is the 500Kg gorilla in the room at 52%." (someone else replies to say that 35% is probably a more accurate figure for Romance, but still a large chunk of the publishing industry).

I will also note one other comment from that post, which fits some of the graphs in your piece:

----------------------- block quote-------------------

I'd like to point you at this 2005 paper by the Author's License and Collecting Society, titled "What are Words Worth?, describing the findings of a study organized by the Centre for Intellectual Property Policy & Management (CIPPM)I, Bournemouth University. Briefly: in the UK in 2004-05, median (typical) earnings for authors were £4000 a year, with mean earnings of £16,531 — that is, while most authors earned very little, a handful earned a lot more and so the mean skews high. Once you discard part-timers and focus on professional authors who spend 50% or more of their time working by writing, the median rises to £12,330 (and a mean of £28,340). Many professional authors supplement their income by teaching or consultancy; restricting the survey to focus on main-income authors (those who earned over 50% of their income from writing) gave median earnings of £23,000 and mean earnings of £41,186.

Interestingly, the researchers went on to calculate a Gini coefficient for authors' incomes — a measure of income inequality, where 0.0 means everyone takes an identical slice of the combined cake, and 1.0 indicates that a single individual takes all the cake and everyone else starves. Let me provide a yardstick: the UK had a Gini coefficient of 0.36 in 2009, the widest ever gap between rich and poor — while the USA, at 0.408, had the most unequal income distribution in the entire developed world. The Gini coefficient among writers in the UK in 2004-05 was a whopping great 0.74. As the researchers note:

"Writing is shown to be a very risky profession with median earnings of less than one quarter of the typical wage of a UK employee. There is significant inequality within the profession, as indicated by very high Gini Coefficients. The top 10% of authors earn more than 50% of total income, while the bottom 50% earn less than 10% of total income. "

------------------- end quote -----------------------