How Netflix Built a $200B Business on Reality Shows and Docuseries. A Statistical Analysis

Why did Netflix go all-in on non-fiction storytelling?

Intro: From Nanook to Netflix

In 1913, explorer and prospector Michael Flaherty was hired to search for mineral deposits along Canada's Hudson Bay. While exploring the Canadian Arctic, Flaherty became fascinated with the lifestyle of the Inuit people and chose to document their daily lives on film.

After nine years of filming, Flaherty released Nanook of the North, a pioneering feat of non-fiction moviemaking depicting the life of an Inuit man named Nanook and his family in the Canadian Arctic. A surprise box office success, Flaherty's film captivated audiences with sequences of daily Inuit life, including seal hunting, igloo building, and family struggles in the harsh Arctic environment (though there are concerns that scenes were staged).

Nanook of the North is often hailed as the first major feature-length documentary, a groundbreaking work of non-fiction storytelling that helped bring vérité filmmaking into the mainstream. In 1989, Nanook was among the first 25 films selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Nearly one hundred years after Nanook of the North revolutionized non-fiction storytelling, Netflix released Too Hot to Handle, a reality dating show where attractive sex-obsessed singles face the challenge of forging genuine connections without engaging in physical intimacy (with a cash prize at stake!). Though Nanook and Too Hot to Handle vary in prestige (to put it lightly), Flaherty's pioneering work of cultural voyeurism oddly paved the way for Netflix's sensational exploration of vanity. Both projects captivate viewers by capturing exotic real-life characters and lifestyles (though that might be where the similarities end).

Too Hot to Handle accumulated over 110M watch hours in its first season and has become one of Netflix's marquee series within a rapidly growing library of non-fiction content. In an effort to consume as much of the world's time at the lowest possible cost, the streaming giant has embraced reality shows and docuseries, padding their media catalog with serialized chronicles of real-life phenomena. So today, we'll explore Netflix's growing repository of non-fiction content and the economics that make this format so alluring.

How Netflix Embraced Non-fiction Storytelling

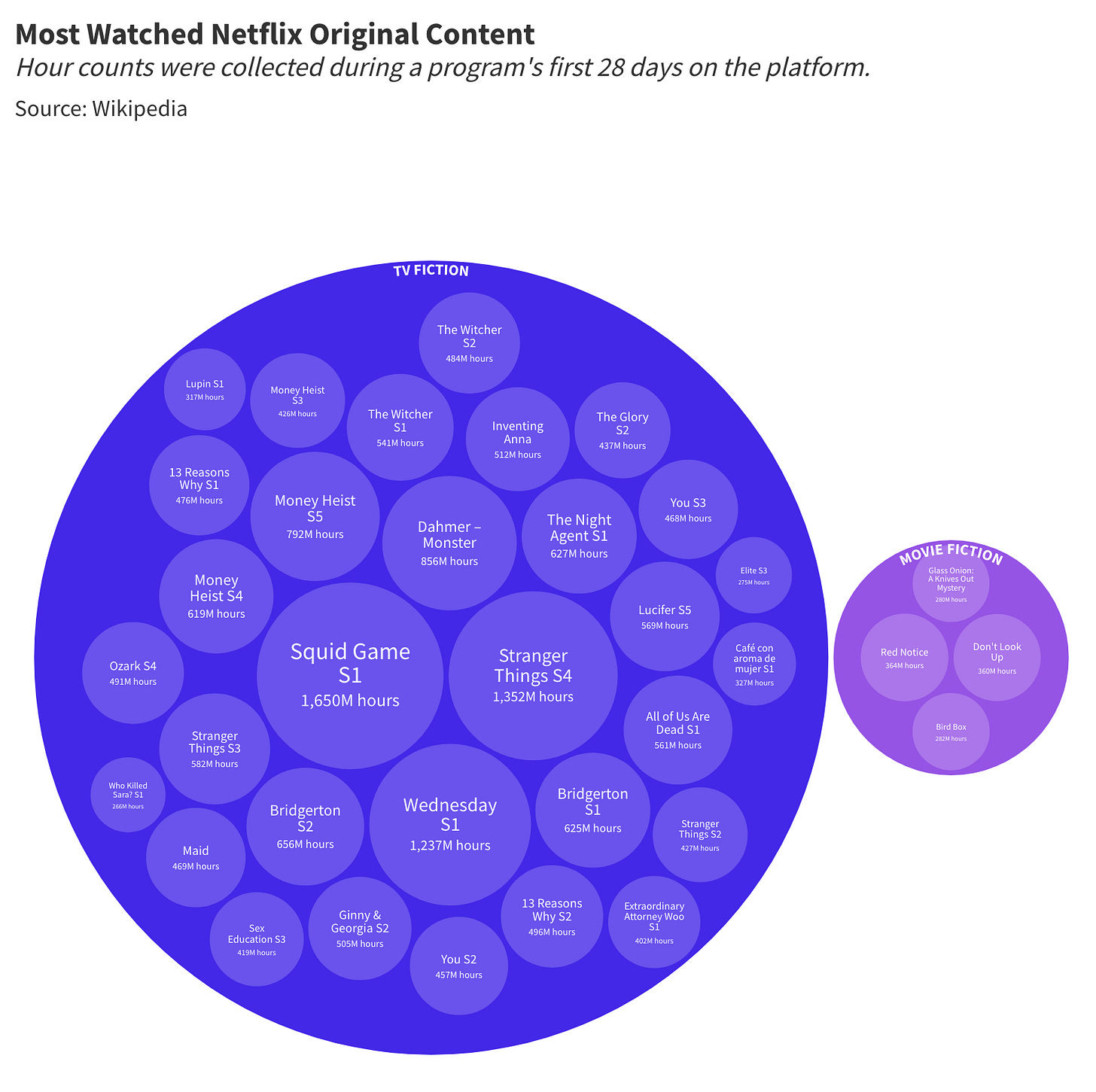

In 2021, Netflix's Squid Game mesmerized viewers with its portrayal of a brutal survival competition pitting financially desperate participants against one another. The show was an extraordinary success, racking up 1.65 billion hours of viewing time in its first 28 days and becoming the platform's most-watched series. The unprecedented global success of Squid Game reportedly raised Netflix's internal valuation by over $900 million.

Indeed, Netflix is often associated with premium, binge-worthy TV. When we look at the streamer's most popular original content, we find a list dominated by glossy television productions that are all works of fiction—media often classified as "prestige TV."

That said, runaway successes like Squid Game and Wednesday are rare. When it comes to programming works of fiction, most streaming platforms employ a portfolio strategy comprised of varying bets. Sometimes, high-priced prestige shows become mega-successes, like The Witcher or Bridgerton, while most of the time, these works achieve moderate success or flop, like Space Force or Marco Polo (shows that I doubt you’ve watched or remember).

At the same time, platforms like Netflix aim to maximize subscriber viewing activity, working under the belief that more user watch time leads to lower rates of customer churn. Therefore, the company needs to produce multiple prestige hits in a given month (an unlikely and expensive outcome) or hedge its risk with a different approach to content production.

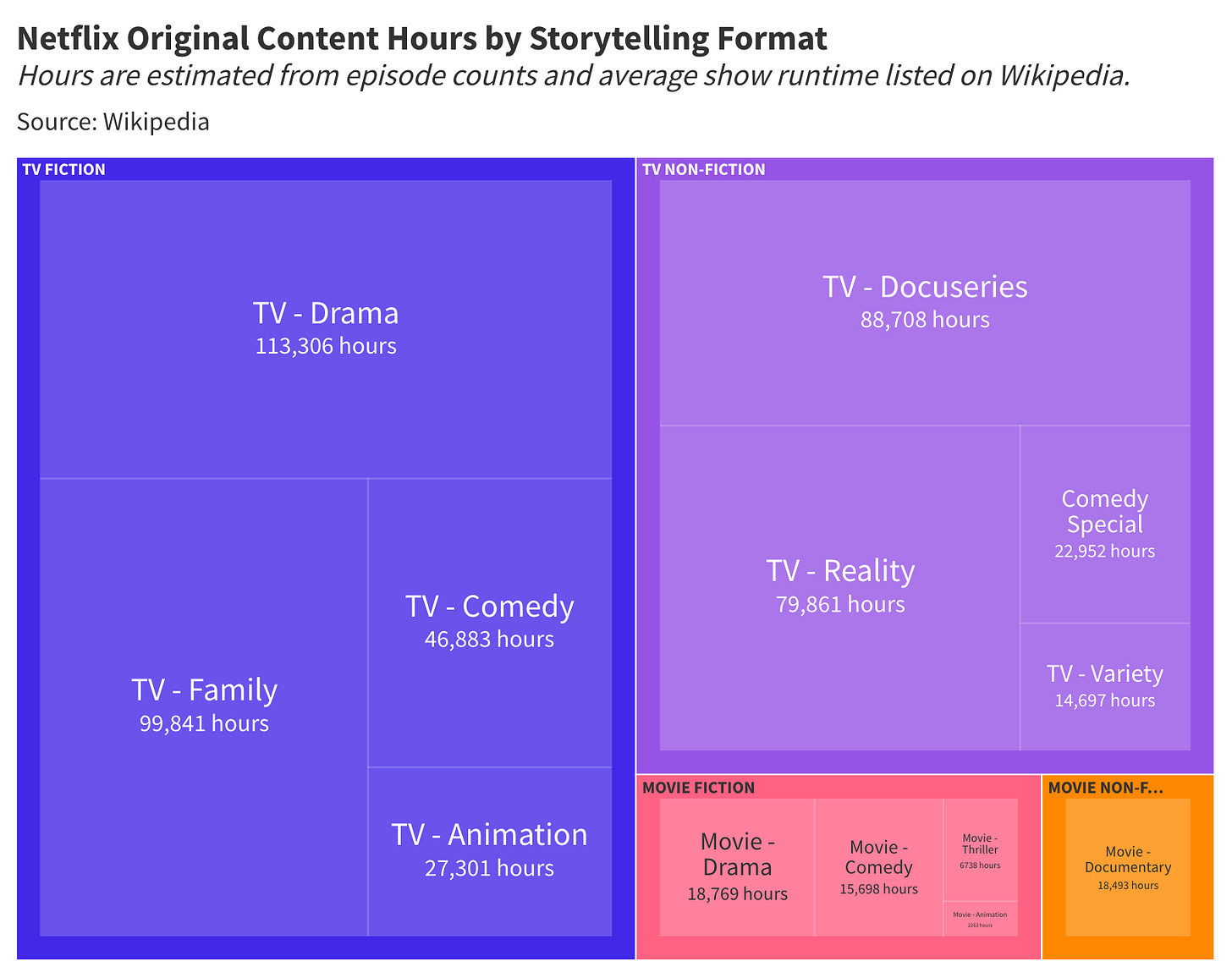

Reality shows and docuseries like Too Hot to Handle, Love is Blind, Making a Murderer, and Last Chance U provide Netflix with engaging, low-cost content capable of regularly entertaining its user base for many hours at a time. These shows don't need to achieve massive viewership to justify investment; they are cheap and people watch them. As such, a significant portion of Netflix's content library (when measured in hours) is dedicated to non-fiction storytelling formats.

But Netflix's programming strategy didn't begin this way. The streamer's earliest productions were marked by prestige projects (all fiction) helmed by vaunted showrunners, including David Fincher's House of Cards, Tina Fey's Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and Jenji Kohan's Orange is the New Black.

It wasn't until 2018 that Netflix began beefing up its catalog with hours of low-cost docuseries and reality content.

The streamer's growing reliance on non-fiction projects is even more apparent when we broadly categorize the format of these newly premiering projects.

In 2023, over 50% of newly premiering content came from non-fiction projects (when measured in hours), with serialized non-fiction (docuseries, reality TV) accounting for 45% and feature-length documentaries comprising 5%. The last six years have marked a renaissance for vérité filmmaking, a storytelling format previously relegated to arthouses and film festivals. Seeing a documentary in 1990 was considered an act of pretension while watching a docuseries in 2023 makes for a typical weekend.

Netflix has increasingly focused on documenting the lives of ordinary people, a notable shift from its initial content creation approach. But what forces drove this dramatic shift toward non-fiction storytelling? Is the streamer's reliance on reality TV and documentaries a fad or the inevitable outcome of economic forces?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

The Glorious Economics of Real-Life Stories

Netflix's The Ultimatum is a reality series that features couples where one partner is eager to marry and the other is reluctant. If the reluctant partner says no to the eager partner's marriage "ultimatum," the couple must split temporarily and explore relationships with other participants who have also faced rejection.

The show is a brutal social experiment that slowly erodes the sanity of its contestants for our viewing pleasure, and audiences loved every minute of it. Season one of The Ultimatum was watched for approximately 144,320,000 hours in its first 28 days. These viewership statistics are all the more impressive when considering the cheap cost of producing the show.

The average reality TV series costs between $100,000 and $500,000 per episode. Using these cost estimates, we can calculate a return on production spend for The Ultimatum. This calculation focuses on the spending required to achieve a single hour of subscriber watch time, with the goal of doing so at the lowest possible cost.

The Ultimatum’s Return on Production Spend for Season One:

Ultimatum estimated cost per episode: $350,000

Number of Ultimatum Episodes: 10

Total cost of production: $3.5M

Total hours watched in first 28 days: 144,320,000 hours

Cost per Hour of Watch Time: $0.02

Netflix is paying approximately $0.02 for every viewing hour the show receives (in its first 28 days). Let's compare these figures with the fourth installment of Stranger Things, Netflix's second most-watched season of television.

Stranger Thing’s Return on Production Spend for Season Four:

Stranger Things cost per episode: $30,000,000

Number of Stranger Things Episodes: 9

Total cost of production: $270M

Total hours watched in first 28 days: 1,352,090,000 hours

Cost per Hour of Watch Time: $0.20

While The Ultimatum may never generate the reach of Stranger Things, the torturous dating show is a more cost-effective way for Netflix to amuse its subscribers.

We can further calculate this cost-per-watch-hour statistic for other Netflix shows and movies across various formats.

Ultimately, non-fiction storytelling is the most cost-effective form of entertainment, followed by television narratives and movies. As a film lover, I find the ROI of movie content unfortunate, as the medium is sadly limited by its two-hour runtime. If Netflix is in the business of hours consumption, it needs formats that can hook viewers for ten hours at a time instead of just two hours. Streamers continue creating movies to provide variety for their audiences, but films are not a strategic priority compared to reality TV or serialized narratives.

So, what does this mean for the future of Netflix's content library? There is a world where non-fiction series increasingly dominate the platform's viewing options as the company optimizes for profitability. At the same time, the appeal of docuseries and reality TV likely has a point of diminishing returns. Not every viewer loves true crime, baking competitions, and dating shows. Has Netflix found the optimal dose of cheaper, non-fiction projects, or will the company increase its investment in this type of content?

Final Thoughts: Because We Like It

My wife loves reality TV and docuseries—she is Netflix's dream customer. Occasionally, I'll watch these shows with her, even though I find them frustrating on a visceral level. On one occasion, I couldn't stand a particular series any longer and asked her, "Why do you watch this stuff?" She shrugged and, matter-of-factly, responded, "Because I like it."

A few weeks later, my wife joined me while I was watching football. I cherish my Sundays watching NFL Redzone, a channel that aggregates game highlights in real-time, thus taking a sport designed for short attention spans and shortening it even more. After an hour of being inundated with non-stop football action, my wife asked me, "How do you watch this stuff?" I couldn't find a way to meaningfully intellectualize my fondness for football, so I shrugged, "Because I like it." She got up and walked away, having proven her point.

I love movies and am deeply committed to discovering and watching as many high-quality, artistically significant films as I can (I’m aware this reads as pretentious). For some reason, I believe content needs to serve some greater purpose. I understand this sentiment is neither universal nor should it be. Most people consume TV and movies to pass a few hours in peace, not as some means of achieving self-actualization. I’m sure most streaming subscribers are satisfied selecting programs displayed in Netflix’s Top 10 instead of boiling the ocean in search of the best possible title, and that’s perfectly fine (whether I like it or not).

Humans have always been captivated by the hardships of other humans. Moviegoers in the 1920s marveled at the struggles of the Inuit. Documentary buffs of the 1990s marveled at fly-on-the-wall chronicles of Hoop Dream's basketball stars and The War Room's presidential advisors. Today's content consumers marvel at gameshow participants, British bakers, dating contestants, and chilling tales of Ted Bundy.

There is no platonic ideal for culture. If something entertained you, then that program was a good use of your time. Netflix excels at entertaining its customers, and doing so with the utmost efficiency.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

That was interesting. It's crazy how much content is out there that I have never even heard of. (Such as the Ultimatum.)

Somewhat related, I have started to grow tired of the serialized TV fiction format. These shows last 8-12 episodes per season, and often probably only really have about half that amount of time of actual useful material, with a lot of filler. And generally the seasons wrap up a story. Then 12-24 months later they come out with another season. I hardly remember any details about what happened before, and in subsequent seasons the plot almost always just starts to spin its wheels. I think it's really hard to create fiction that can last for dozens of hours of story telling.

Movies are nicer because the whole story is contained in 90-120 minutes. And when it's over, it's usually over. No more tedious plot padding in future episodes.

The weird part is, when I sit down to watch something, starting a 120-minute movie either: a) feels like too much of a commitment for the evening (even though if I end up watching a TV series I'll probably watch 2 or 3 episodes) or b) I feel like I need to "save" the movie for some abstract "better time". So then I end up watching a TV series.

I like also films, not the other stuff. And never, never, such TV 📺 episodes.