How Much AI Will Audiences Accept in Music and Movies? Quantifying Where Consumers Draw the Line on AI Art

Unpacking public sentiment around AI in filmmaking and music production.

Intro: A Synthetic Celebrity

For a brief moment, it looked like Tilly Norwood would be Time magazine’s Person of the Year. If you’re unfamiliar with Tilly Norwood, then congratulations on missing some mind-numbing AI news coverage.

For those who need a refresher: Tilly Norwood is an AI-generated “actress” created by a British startup called Particle6. In September 2025, reports emerged that Hollywood talent agencies were scouting this large language model output as if she were a real performer. These claims were dubious, given that no credible agency would sign an LLM at the expense of alienating their client base of real human actors, but that didn’t stop a deluge of half-baked think pieces about the end of human performance as we know it.

For one tedious week, Particle6’s creation dominated social media feeds, igniting debate over which aspects of media production could—or should—be handed over to AI.

The machine intelligence known as “Tilly” represents an extreme example of AI-driven job displacement in the entertainment industry. If you imagine a spectrum of what viewers will accept, AI actors would likely fall at the very end—precisely because of the parasocial bonds we form with Julia Roberts, George Clooney, or Timothée Chalamet.

Which got me thinking: if AI adoption exists on a spectrum, how much is too much? When are audiences willing to tolerate AI-generated elements—and where do they draw the line?

So today, we’ll dive into the messy, often contradictory, discourse surrounding AI-generated art, and examine which aspects of entertainment audiences are most eager to protect.

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by Khaki.

Subscribing to newsletters is easy; reading them should be too

I’ve been trying out a free app for reading newsletters called Khaki. The interface is clean, distraction-free, and only shows the newsletters I’m subscribed to, no noise of everything else in my usual inbox.

Sign up with access code NEWSLETTER to try it for yourself.

How Much AI Will People Tolerate in Their Art?

Asking someone if they “approve” of AI is like asking somebody how they “feel” about Winter.

There is a big difference between a question about a season in its totality versus something like “how do you feel about Winter when you’re wrapped in a blanket, eating toasted chestnuts, and listening to ‘Last Christmas’ on repeat?” Most people have a gut reaction to a high-level query about a three-month period, but a meaningful answer requires greater specificity.

Consider two open-ended questions from a pair of recent YouGov polls:

In April of 2025, 56% of poll respondents expressed support or indifference toward LLM-generated songs.

Meanwhile, 61% of respondents considered LLM use during filmmaking to be “acceptable” or were “not sure.”

At a macro level, it appears most people endorse art generated by large language models or have no opinion on this world-changing technology.

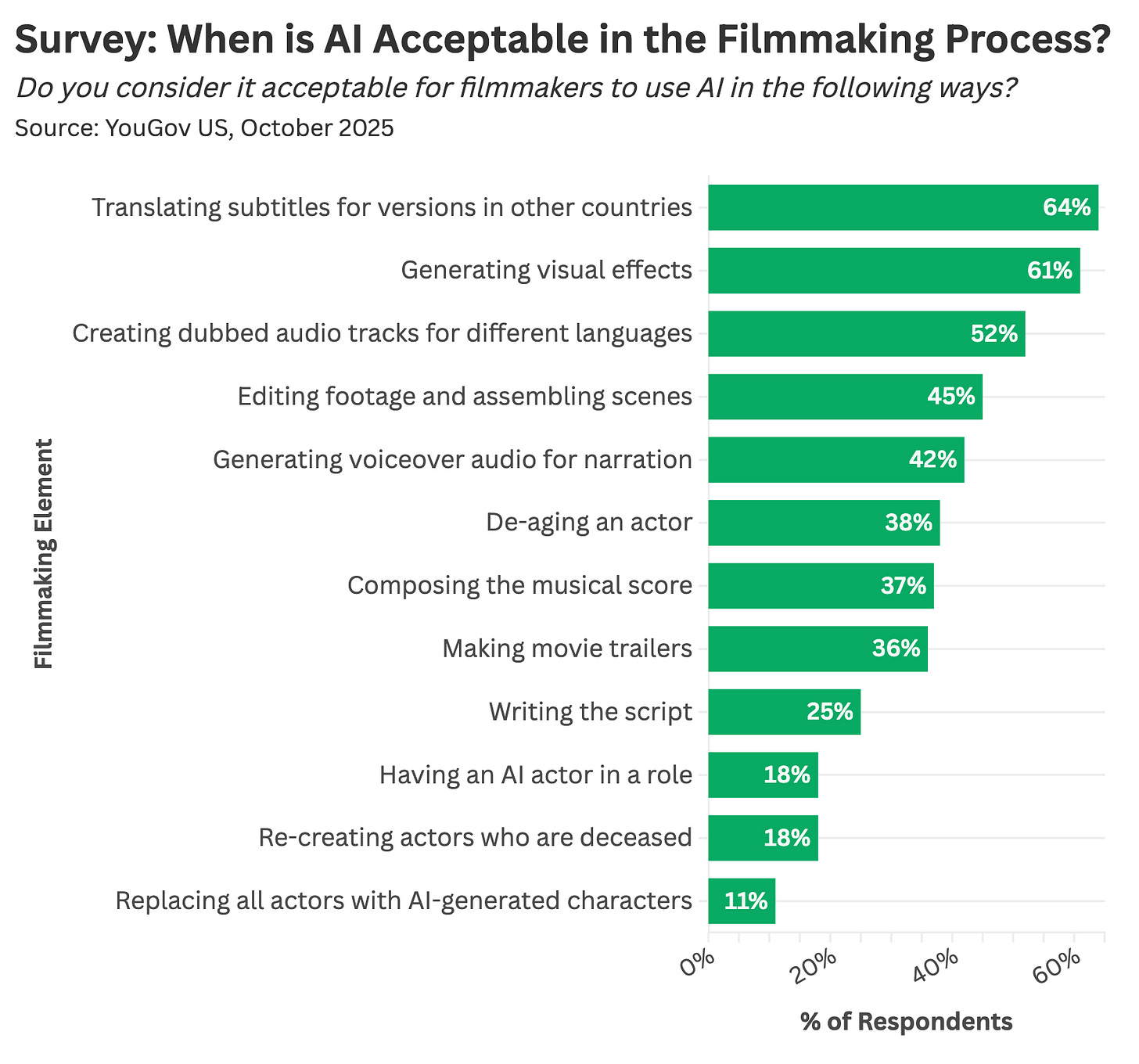

Fortunately, these surveys also asked in-depth follow-up questions. Those who initially had “no opinion” on AI in film changed their stance when probed on various aspects of video production—from special effects and dialogue translation to performance, voice replication, and digital de-aging. Respondents were generally supportive of using artificial intelligence for visual effects and dialogue translation, but overwhelmingly opposed generative AI replacing human actors and screenwriting.

Reading between the lines, it seems relatability is a major predictor of these opinions. The more emotionally resonant—i.e., ostensibly human—an element is, the less willing respondents are to see it replaced by machine intelligence. Thankfully, there are limits to what can be automated.

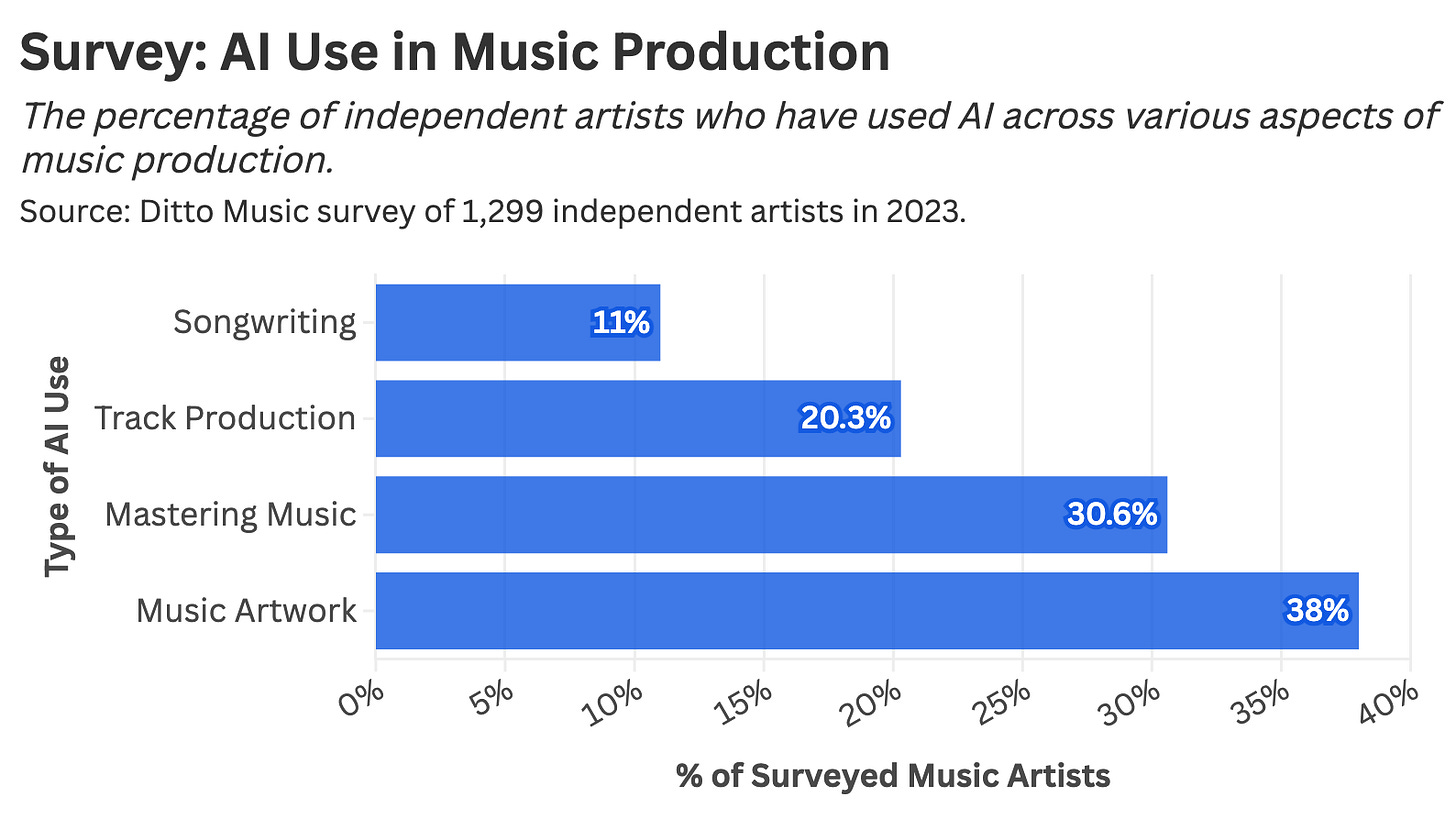

We see similar sentiments in the music industry, where 60% of independent artists admitted to using AI in some form, though primarily for music mastering and promotional material. Meanwhile, songwriting and vocals, aspects best understood by listeners, have remained largely untouched by LLMs (to date).

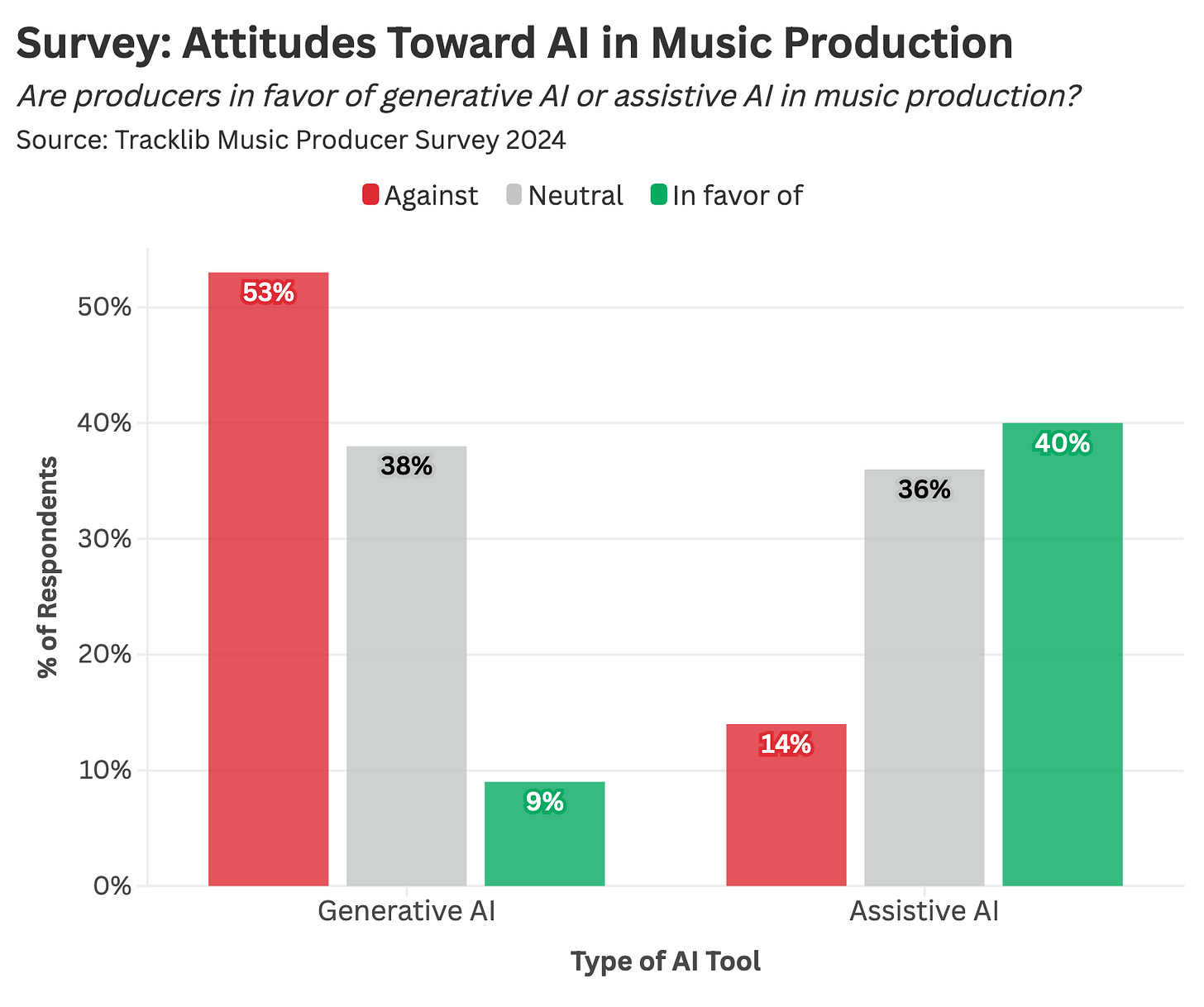

Throughout my research, a key distinction emerged between generative and assistive artificial intelligence—specifically how each supports (or negates) human authorship.

Generative AI creates new content—such as text, images, or audio—by learning patterns from existing works. This model output typically replaces the creative process in its entirety.

Assistive AI, by contrast, supports human creativity through process automation without generating an entire artwork. If you’ve ever used iMovie to auto-adjust lighting or clicked a button in GarageBand to remove background noise, you’ve experienced assistive AI in action.

A 2024 poll of music industry professionals reveals a sharp divide in attitudes toward these approaches: producers were far more supportive of AI enhancement (assistive) and deeply skeptical of full-on replication (generative).

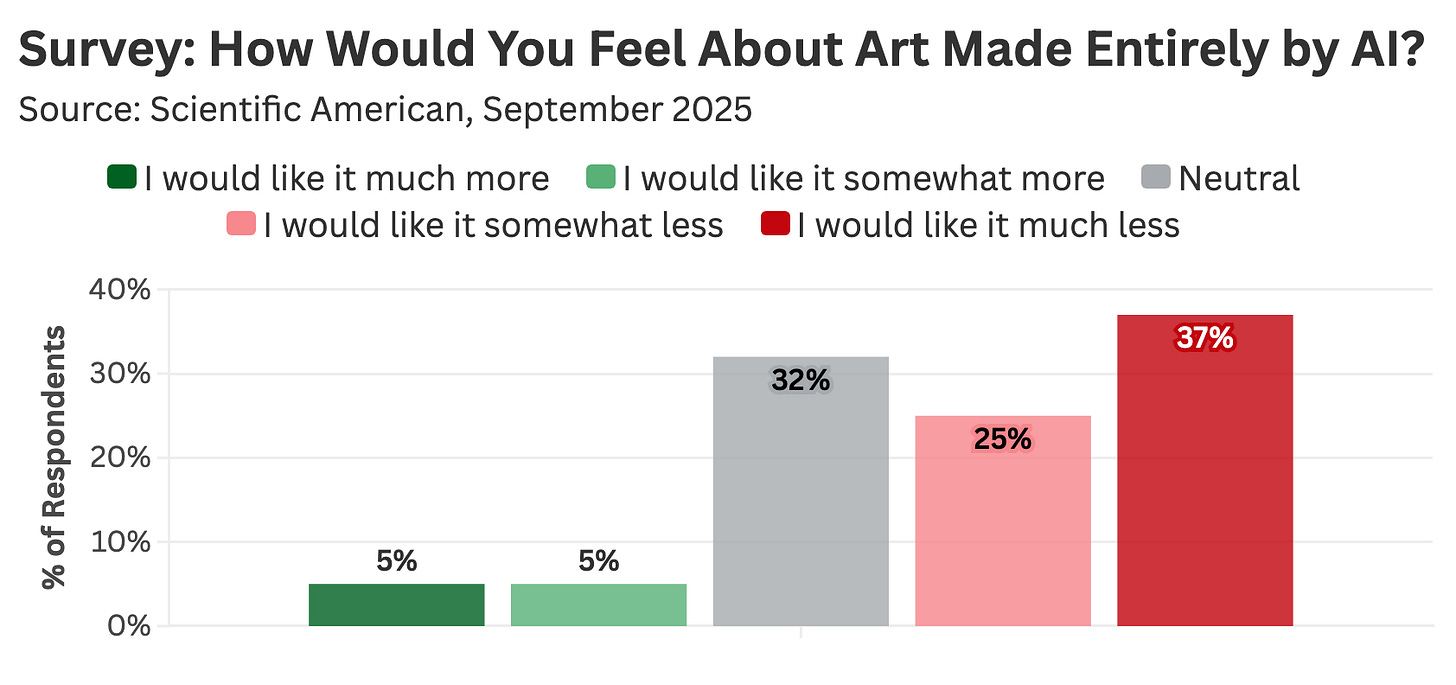

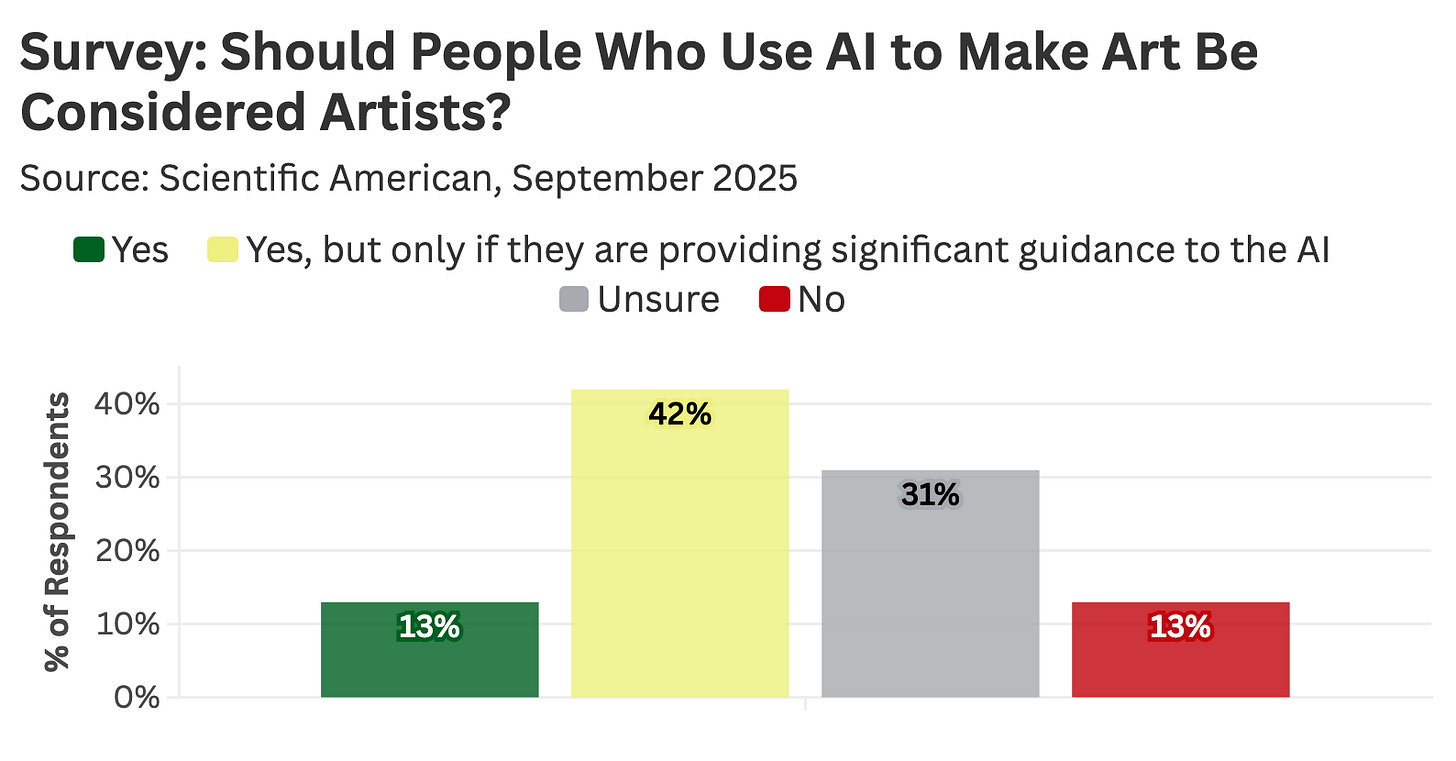

Similarly, a recent poll conducted by Scientific American found strong disapproval for art produced without meaningful human involvement (which is a relief!). Yet when asked whether users of large language models should be considered “artists,” most respondents said yes—so long as those users provided substantial creative direction to the tool.

Reading the tea leaves of these surveys, it seems that two key factors drive public attitudes toward AI art:

Relatability: People are less comfortable automating elements of creative expression they understand—like acting, singing, or writing—because they are more likely to form an emotional attachment to these aspects.

Human Input: Most viewers comprehend what it means to click a button in Photoshop and let an algorithm enhance an image—but they’re far less comfortable with that same image being produced by Sora (OpenAI’s image generation model). For many, meaningful art hinges on human intention and authorship.

Of course, all of these opinions are contingent on one crucial factor: the ability to recognize when AI is being used. And that’s getting harder by the day.

Multiple studies have shown that consumers struggle to tell whether an artwork—be it an image or a poem—is human-made or produced by a large language model. You can’t object to an AI-generated actor or screenplay if you don’t know it’s synthetic.

People may accept certain applications of AI in media, but not if they’re being deceived. A February 2025 YouGov poll found that 86% of consumers believe creators should disclose their use of AI in media production, and 78% supported greater AI regulation, citing concerns over artificial content. Viewers want to know when an LLM is responsible for voiceover narration, a gaggle of background extras, or a nonexistent lead actor.

Of course, the government will (likely) do little to mitigate these concerns, which brings me to a half-baked startup idea: a scorecard for content “organic-ness.”

This totally-awesome-business-that-I-will-not-start™ would function like Common Sense Media, but instead of grading age-appropriate aspects of film and television, it would evaluate LLM usage in media production. Imagine Common Sense’s scoring categories (e.g., “Positive Role Models,” “Drinking & Drugs”) repurposed for artistic authorship:

Music Vocals: ★★★☆☆ — Human-created, but mastered with Claude

Beats: ☆☆☆☆☆ — Entirely synthetic, produced by Suno

Music Video: ★★★★☆ — Filmed with real actors and a camera crew, but uses background explosions generated by Sora

As AI-generated media becomes more common, audiences will need reassurance that what they’re watching is human-made (at least for those who value this distinction). Ideally, a for-profit business will meet this demand—because we need a startup to solve the problems created by other startups.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: At the Top of the Slippery Slope

I recently watched a perfectly solid horror movie called Late Night With the Devil. After it ended, I went to Letterboxd expecting to find like-minded faint praise. What I found instead was vitriol.

Apparently, at some point in the movie, generative AI was used to create a few graphics for a fictional talk show. Had I watched this film 100 times, I never would have identified this LLM output. My best guess is that news of AI involvement leaked online, prompting people to hate-watch the film and leave comments like:

“It actually feels insulting...like the filmmakers don’t give a shit and want to let you know that you’ll accept blatant AI in [a] 1970s period piece.”

“I wish I never spent money to go and see this. Being an artist has never felt so hopeless.”

“Didn’t know AI Art was this popular in the 70s”

Throughout my research for this essay, I was continually surprised by how many survey respondents were “not sure” or had “no opinion” on machines overtaking human expression. Who are these decidedly neutral individuals? Do they feel anything?

Yet, as much as I hate to admit it, my immediate reaction to Late Night With the Devil’s AI usage was overwhelmingly neutral. Perhaps I’m an unfeeling drone who hates art.

But there was one Letterboxd review that recontextualized this AI logo in a way that stuck with me:

“As a graphic designer, even if I enjoyed the movie or not, I cannot rate it any higher because of the use of AI. We cannot let this become the norm.”

Usually, I dislike slippery slope arguments, since anything can be framed as the first step toward catastrophe. While there are compelling slippery-slope opinions, I’ve mostly seen this tactic used poorly. But in this case, I get it. Today, it’s a stupid logo or cutaway graphic—tomorrow, who knows.

Imagine a single frame of a blockbuster—say, a Fast & Furious car chase through a crowded urban center with explosions lighting up the background. One can envision every element of the frame gradually replaced by generative AI: the extras, the debris, the cars, the fireballs. Fifty years from now, that entire scene might be rendered in a minute by some ChatGPT descendant. AI users will start at the edges of the frame—automating secondary details—and work their way toward the center, slowly but surely.

Am I putting too much stock in one online review? Probably. But I’d also prefer my Vin Diesel car garbage be 100% organic—as certified by a hypothetical-content-labeling-startup-that-somebody-else-will-create™. You may not mind visual effects automation or LLM dialogue translation, but who knows where this complacency leads. It’s these small, accumulating concessions that open the door to a future where the things we claim to care about are quietly replaced by AI slop.

Today, the danger isn’t one Tilly Norwood in close-up. It’s a hundred Tilly Norwoods quietly filling in the background—unbeknownst to audiences—and where things could go from there.

Stat Significant is moving to a tip-jar model! All posts will stay free, but if you’d like to support my work, you can contribute in a few ways:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,700 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

Wow, the part about Tilly Norwood and those dubious agency claims really stood out to me, such a smart take. This piece builds so well on your earlier discussions about the ethics of AI development. As someone who teaches CS, I'm always thinking about where we draw the line. It's truly a complex spetrum, especially when you consider those human connektions with actors.

This is great content. Thank you for taking the time to write this.