How Movies Shape Us: A Conversation with Walt Hickey (FiveThirtyEight, Business Insider)

For this week’s post, I spoke with Walt Hickey, data journalist and author of the new book You Are What You Watch.

As the former culture editor at FiveThirtyEight and current deputy data editor at Insider, Walt is no stranger to crafting compelling stories with data. You Are What You Watch sets out to empirically prove that entertainment is one of the most powerful forces in the world, influencing everything from business to politics to commerce.

My conversation with Walt covers:

His journey from mathematics to data journalism and highlights from his time at FiveThirtyEight.

Some of the most surprising pop culture insights from his book.

Whether there are downsides to quantifying creative expression.

I hope you enjoy my talk with Walt, and I highly encourage you to check out You Are What You Watch.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Daniel Parris: Your academic education was in mathematics, but you ultimately applied your skillset to data journalism. Why did you pick this domain, and why did you decide against careers in finance or tech?

Walt Hickey: I started college with the idea of a quant-based career. As a counterweight to that, I worked for the student newspaper at William & Mary, and it gave me an early and ardent love for journalism as an art and profession.

Throughout my time in college, two remarkable things were going on in journalism:

This guy Nate Silver, who I'd been familiar with in high school, got an opportunity to start applying his trade at the New York Times and was expressing the idea that data journalism can have efficacy outside of areas where it had traditionally been used, which was mostly limited to economics.

You saw a ton of inspiring journalism in the wake of the financial collapse about how data and numbers had, in many ways, precipitated the collapse.

There was a discrete example of combining data and journalism in Nate, as well as some compelling people demonstrating that an aptitude for numbers lent itself to ambitious work. I ended up taking the chance and pursuing [data journalism].

DP: After graduating college, you interned at Insider and eventually made your way to FiveThirtyEight, where you became their culture editor, writing stories on Nicolas Cage, Oscar predictions, and Halloween candy power rankings. What do you enjoy so much about quantifying popular culture?

WH: Nate brought me into FiveThirtyEight to do lifestyle coverage, and I really enjoyed it because it's so open-ended. For economics, politics, sports, and science, the data you work with is pretty finite, whereas with lifestyle and pop culture, you have to make your own luck. It was an exciting challenge to find ways to express cool stories about the movies we watch, the things we do, and the events we attend—all that through data.

DP: Was there any one story you're particularly proud of during your time at FiveThirtyEight?

WH: I worked with my good friend Neil Paine on a story about the Madden video game. We wanted to understand what went into Madden's player ratings. We wanted to find out what a normal dude would look like in the game of Madden.

I just so happen to be a normal dude, so I got to go down to their lovely campus in Orlando and run the combine as a normal dude. They put me in the game to simulate what happens if you have a normie. It was really fun because it helped us understand how this quantification system distills a myriad of talents within the NFL into a digital format and how to understand the data behind that.

I had an overall rating of 11; the lowest in the actual game is about 65. [The story] gave us insight into how talented the NFL is and a look inside a really exciting dataset.

DP: During your time at FiveThirtyEight, what did you learn about packaging statistical analyses for mainstream audiences?

WH: The point of data journalism is different than the point of data analysis. Data journalism must reach an audience; otherwise, you are not doing journalism. You need to do what you can to make things accessible. That can be writing in a down-to-earth manner or picking topics people find inherently interesting so they're willing to take the leap on the stats and data involved.

The second thing is a more compact piece of advice, which is that a chart should have the same function as one paragraph. A good paragraph has one idea it's trying to convey. Like a paragraph, your chart should make one point, and [the takeaway] should be:

Look at the direct relationship between these two things.

Look at this outlier.

Look at how this has changed over time.

DP: What is the elevator pitch for You Are What You Watch?

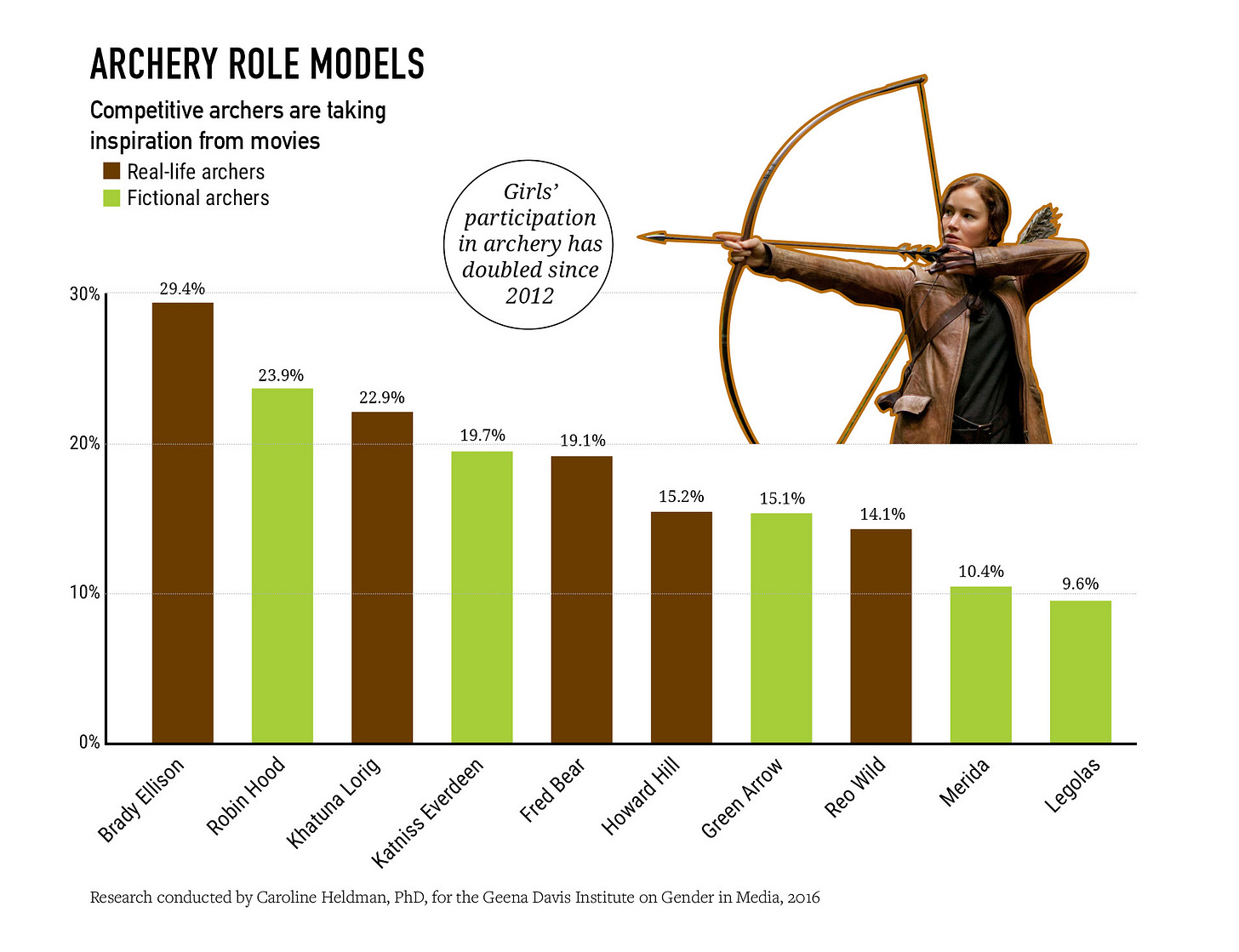

WH: Over the course of reporting at FiveThirtyEight, I kept circling one big story. I kept talking to people who had their lives changed by pop culture in some capacity. Maybe they saw a movie and understood that people like them could enter a career that otherwise didn't seem accessible, or maybe [a film or TV show] interested them in a new hobby or country.

I kept hearing these things and realized that, on some level, movies and television have a remarkable impact on who we are as people. So, I embarked on the book to explore that, and I was shocked at how much I found.

Whether it's your physiology when you watch a horror movie, how a movie featuring a dog leads to spikes in the popularity of that dog, or how different countries use their film industries as diplomatic enterprises, you see the effects on every single level.

The subtitle of the book is how movies and TV affect everything. By the end of the book, I was convinced that this stuff really does affect everything.

DP: Out of all your research for the book, what was the most surprising thing that you found?

WH: The really surprising thing was the physiological effects of movies. Movies are not simply a visual experience or an audio experience, but your body goes for a ride. We can track your body's reaction to a film in real-time by checking the conductivity of your skin or the chemicals your body exhales. The chemical reactions are unique from film to film but are repeatable across different audiences for the same movie.

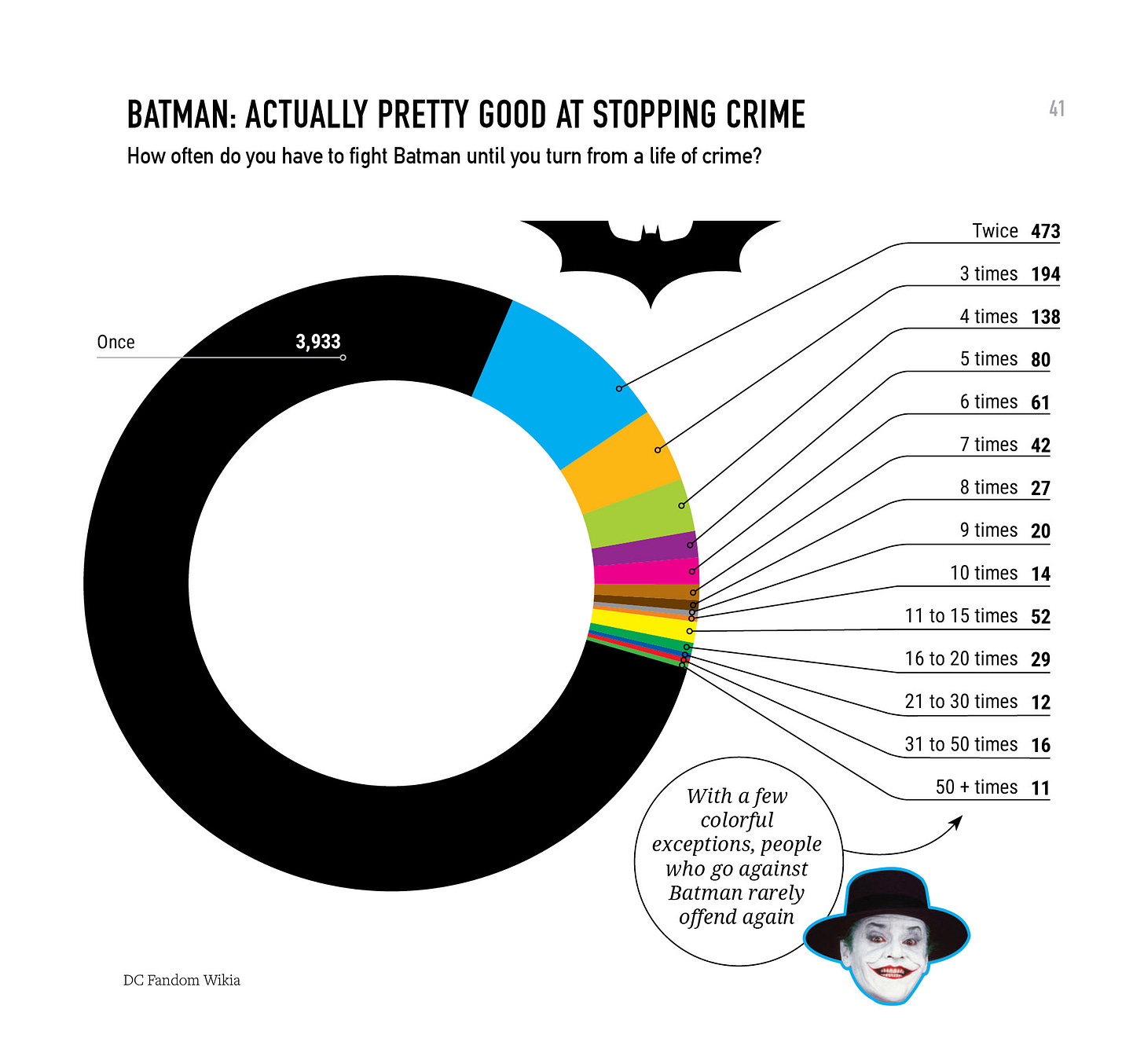

DP: My next question is about your Batman crime-fighting analysis. Why quantify Batman's crime-fighting efficacy? What do you view as the greater significance of this analysis (and others like it)?

WH: You're referring to a really fun chart that I've always wanted to make. There's this idea in some internet circles that Batman might not be good at his job. He arrests people, sends them to Arkham, and then two weeks later, they just break out again. I wanted to see if this theory was true.

I scraped the wikis for the DC Universe and Marvel, which are very comprehensive histories of these comic books throughout their entire lifetimes. And then I tracked how often [Batman villains] come back to determine the recidivism rate of these characters. I found that most villains are one-hit wonders. They fight Batman once and are never seen again in the criminal underworld. There are a few outliers, but Batman's not that bad.

We have a very pervasive superhero moment going on right now. Taking some of these things at face value, investigating them, and seeing how they hold up was a fun thing that I got to do throughout the book.

DP: As someone who's constantly examining popular culture, is there any downside to quantifying creative expression, or is this question kind of overthinking things?

WH: In the book's introduction, one of the pictures I have is Moneyball. I think it's a magnificent film; it's also an important story to my craft.

You cannot look at the sport of baseball after Moneyball and say that it's the same thing that it was. People stopped stealing bases, the defensive work collapsed, and the game became about who could throw the fastest ball and rotate the most pitchers. Over the past couple of years, that caused a decrease in baseball interest. It caused all sorts of negative things that, while optimal, were nevertheless negative.

That terrifies the shit out of me when it comes to pop culture. I do this work because I genuinely love movies. I enjoy the richness of what these things can do for us, so I have always been cautious. There have always been companies consulting with Hollywood on building the perfect movie, and that is just so remotely uninteresting to me.

The way that I worked on this book—taking movies and TV at face value and exploring what they were trying to say—I think there's more soul in that than how we typically talk about pop culture online. I'm not interested in making movies make more money. I care about the results—I care about the actual films they make.

I'm always concerned the thing I'm doing makes the thing I love less meaningful, and that never happened when I was making this book.

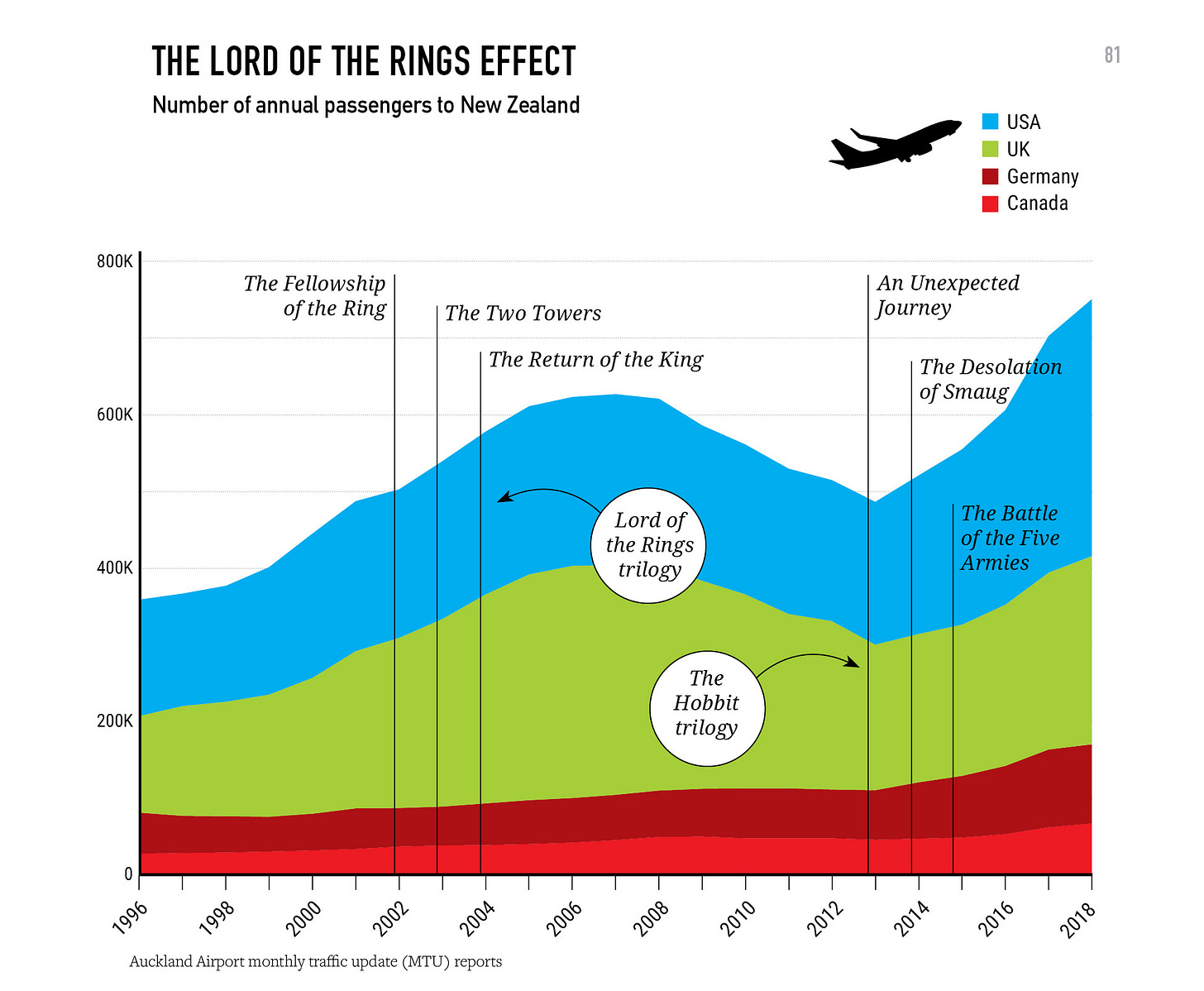

DP: One of your analyses focuses on the Lord of the Rings series’ impact on global tourism. Were you surprised to see such a strong relationship between the films and travelers to New Zealand? And why do you think the setting of these movies has such a strong hold on audiences?

WH: You're referring to this great chart in the book that tracks arrivals at Auckland International Airport from Europe and North America. [The arrivals trend] is steady, and then the three Lord of the Rings movies come out, and there's a little peak. A few years later, it starts going down, and then they make The Hobbit movies, and it peaks a little higher.

These films are a love letter to New Zealand in many ways. I researched how tourism and movies intersect, and there's a lot of good academic work there. You can see how Downton Abbey leads people to visit English country houses at a rate never seen before. Even a silly little murder show set in a small town in the Netherlands on Netflix can cause a significant increase in travel there. A movie can introduce people to places they never considered visiting, and they'll go there in droves.

DP: What was your "white whale" analysis for the book?

WH: A few charts in the books are just things I've always wanted to know. One of them: is Ash Ketchum a good Pokemon trainer? [This analysis] is a two-and-a-half-page spread in the book.

So, the first thing is to define what a good Pokemon trainer is, an idea similar to wins-above-replacement. How many wins would we expect [any trainer] to get in a given contest? And then, how often does Ash Ketchum win [that same contest]? The difference between the two numbers is what Ash adds to the equation.

This analysis necessitated 4 billion simulations of Pokemon versus Pokemon battles. Each Pokemon fought every other Pokemon something like a hundred thousand or a hundred million times. It was great. It took my computer about two days to run that simulation, and then I built a model to design the probabilities. I am just so proud of the results.

DP: Last question. What do you want readers to feel after finishing the book?

WH: Television isn't just something you throw on in the background—it's not something you waste time doing. Movies are not a distraction. It is an active decision to watch these things, and they are having an effect on you, and that effect is often neutral to good.

Roger Ebert had this concept that movies are empathy machines—that they show you a world you yourself could not inhabit. You have limited time on this earth, and the time you spend consuming culture, thinking about it, and seeing new perspectives is time well spent.

Loved the conversation & learned a lot!