How Movies Make Money After Leaving Theaters: The Economics of a Film on Streaming

Unpacking a film's financial afterlife once it leaves theaters.

Intro: Art and Commerce

Most movies are privately financed, creating a constant tug-of-war between art and commerce. Some projects lean toward the commercial—think Marvel, music biopics, lega-sequels, or anything starring Vin Diesel. Others skew toward the artistic, often marked by 20-minute film festival standing ovations. But once in a while, a film strikes a rare balance: offering big-budget spectacle that earns critical praise, delights general audiences, and elicits extended applause from festival-clappers. These are the unicorns of modern cinema—Poor Things, Oppenheimer, Barbie, Everything Everywhere All At Once, and most recently, One Battle After Another.

Yet the extent to which One Battle After Another balances art and commerce is of great debate (at least online). The film currently holds a 95% on Rotten Tomatoes, is the frontrunner for Best Picture, and is projected to earn around $200 million globally by the end of its theatrical run. The catch? With a production budget of $130 million, considerable marketing spend on top of that, and theaters taking 50% of box office revenue, the film will not break even from ticket sales alone.

Industry coverage has responded by shaming those responsible for the film:

Slash Film wrote an article titled “5 Reasons Why One Battle After Another Flopped At The Box Office.”

Variety quipped, “One Battle After Another Projected to Lose $100 Million Theatrically.”

The BBC offered an explainer on “Why the year’s most acclaimed film flopped.”

These are the same writers who bemoan Hollywood’s reliance on intellectual property and the industry’s aversion to original storytelling. I could spend a few paragraphs unpacking this hypocrisy, but there’s a lot to cover in this essay, so I’ll just say this: these articles are the worst.

Most baffling about this industry coverage is its myopic focus on box office, with no mention of the revenue this film will generate on streaming—a glaring omission that applies to most post-pandemic releases.

So today, we’ll demystify the economics of films once they leave theaters, unpack the myriad complexities that muddy these calculations, and explore why industry coverage is ill-equipped to track this evolving financial model.

The Before Times: VHS and DVD

In the before times, there was physical media. If people liked a movie, they might end up paying for it five times: first in theaters, then on VHS, later on DVD, followed by Blu-ray, and maybe today as a 4K disc. That’s nearly $120 spent on The Goonies or Raiders of the Lost Ark.

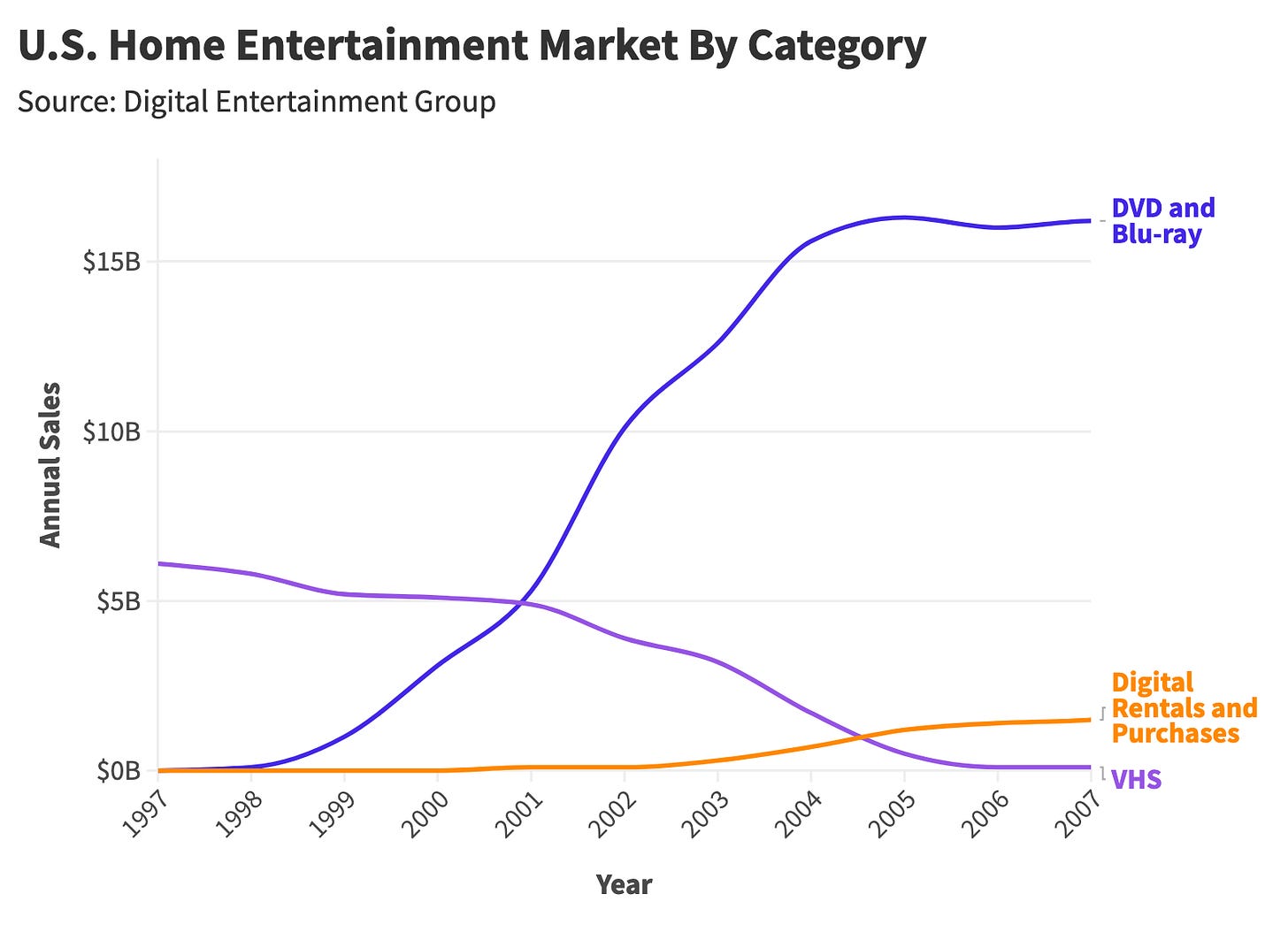

In the early 2000s, DVD sales topped $16 billion annually—tripling the size of the home video market first established by VHS.

This dependable revenue stream allowed studios to take bigger risks. If a film underperformed in theaters, strong DVD sales allowed those projects to turn a profit.

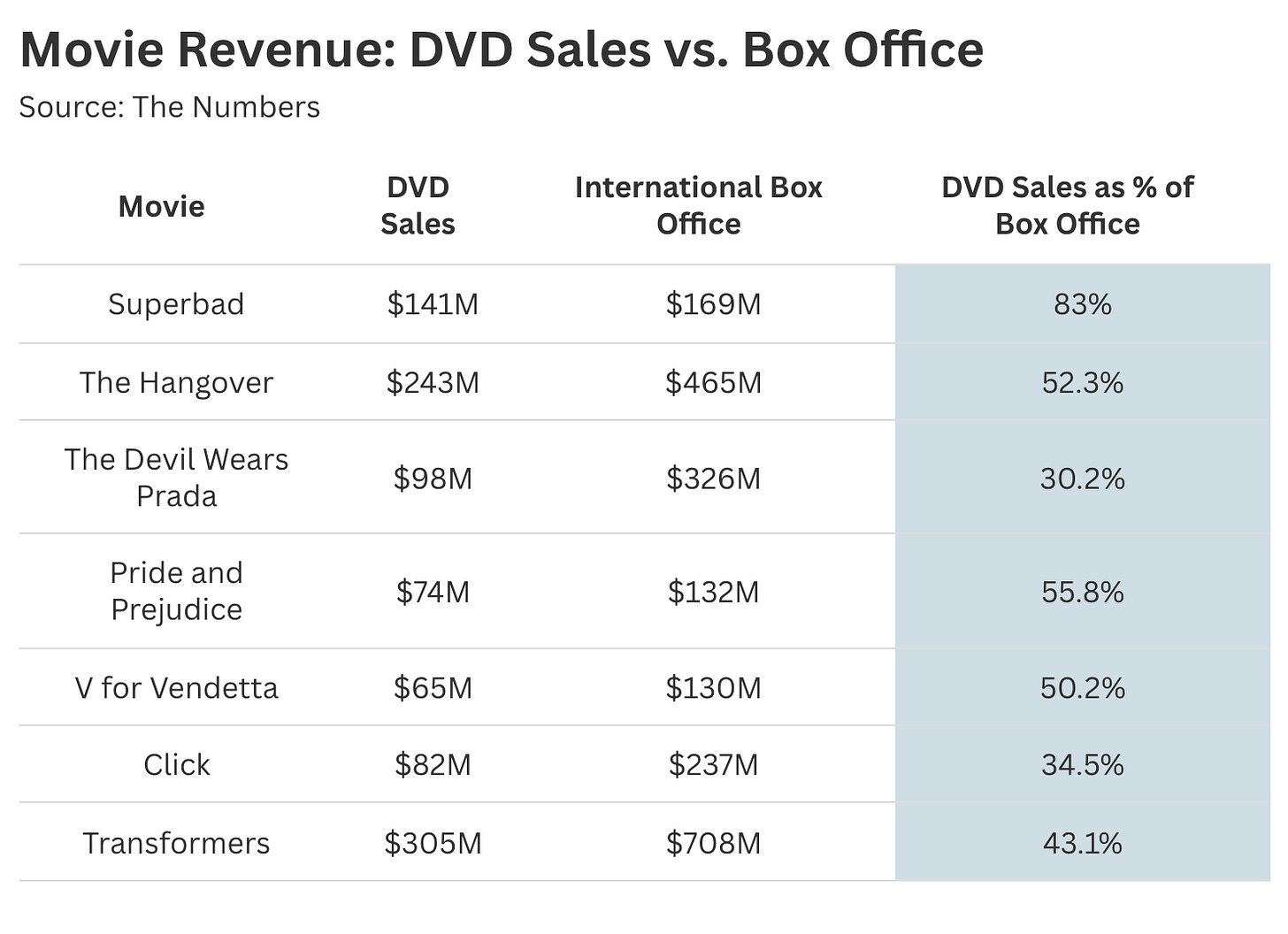

Based on a handful of case studies from the early 2000s, it appears DVDs generated revenue equivalent to roughly 50% of a film’s international box office.

In many cases, cult classics like Napoleon Dynamite, The Big Lebowski, or Fight Club earned as much—or even twice as much—from physical media as they did in theaters.

It was a golden era for movie studios, who managed to mitigate risk in an otherwise volatile industry. For consumers, however, it meant paying more for less—at least by today’s standards.

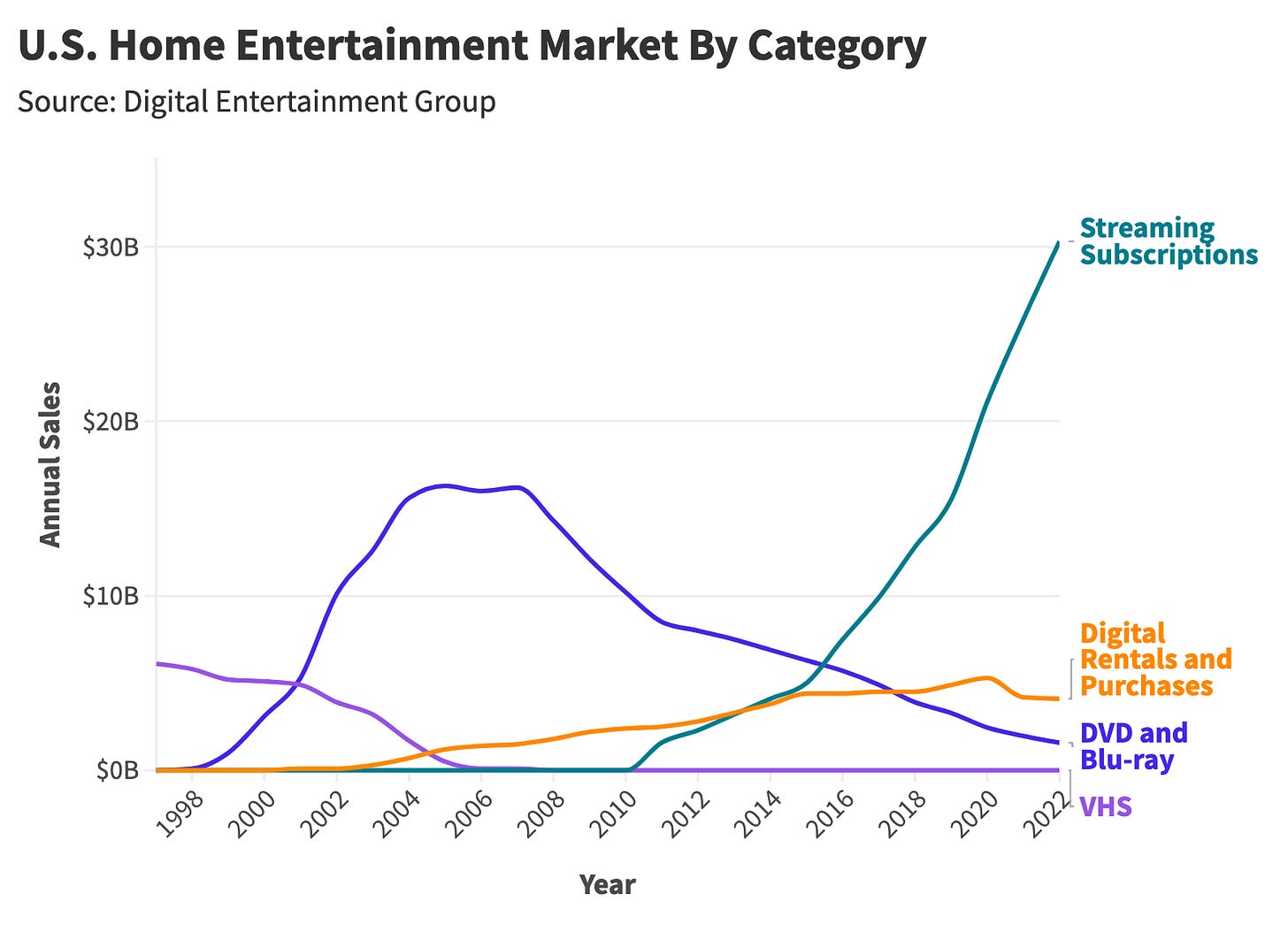

In 2007, Netflix launched its streaming service, and the rest is history. Today, the DVD market sits at $1 billion, comprised of streaming holdouts and movie nerds (like me!).

Which raises the question: how did this paradigmatic shift alter the value of a movie once it exits theaters?

Post-Theatrical Revenue Stream #1: Video on Demand

The first stop in a movie’s post-theatrical afterlife is video on demand (VOD).

Roughly 30 to 90 days after its theatrical release, a film becomes available for digital rental or purchase on platforms like Apple and Amazon. Consumers can pay anywhere between $3 and $20 to rent a movie for 48 hours.

As much as I love the theatrical experience, I have to admit this model is incredibly convenient—and surprisingly cost-effective, especially if you’re watching with a group.

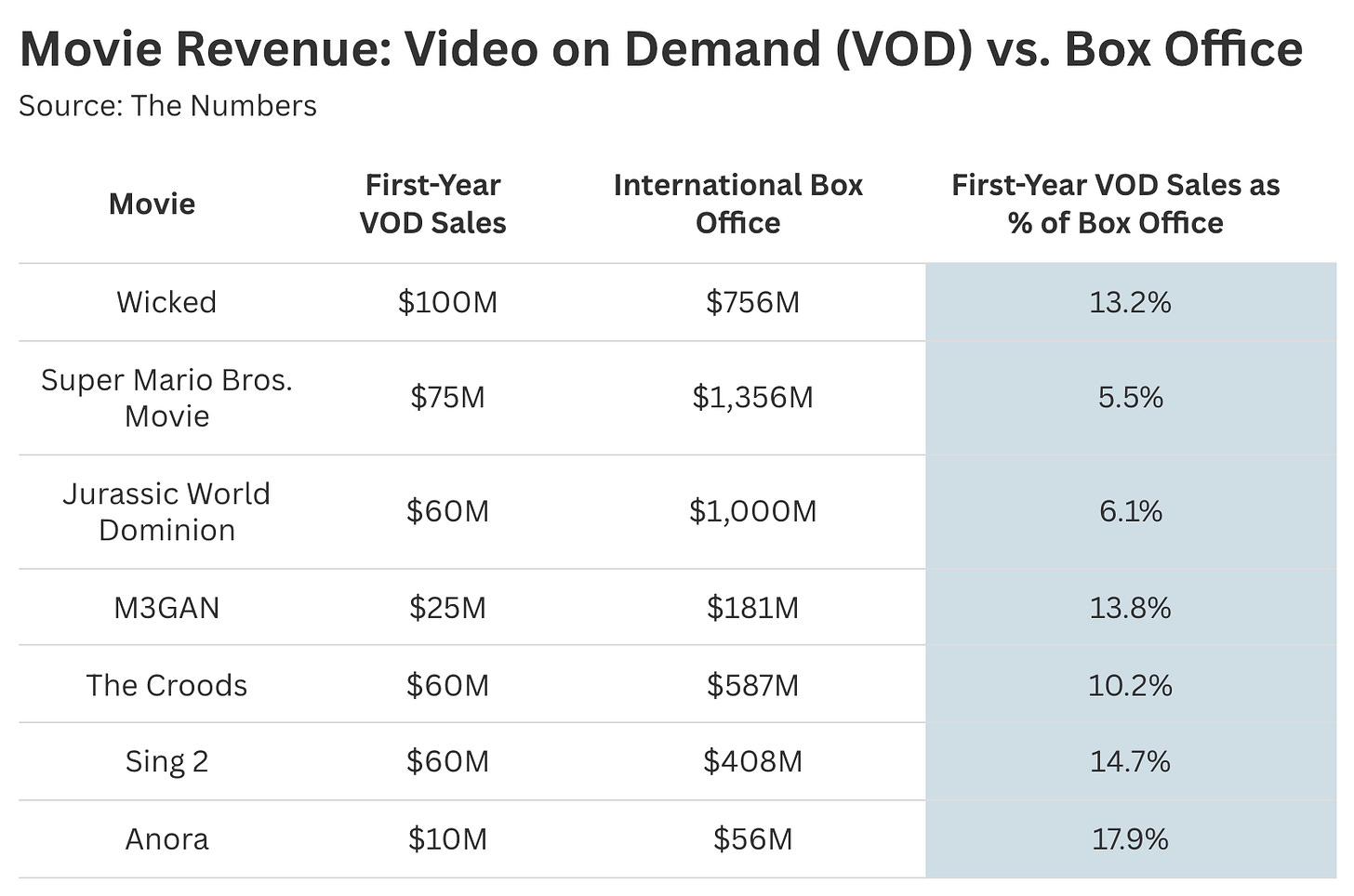

Unlike box office data, which is publicly reported and meticulously tracked, VOD revenue is a black box. Still, a handful of recent data dumps can help us piece together the economics of this post-theatrical window.

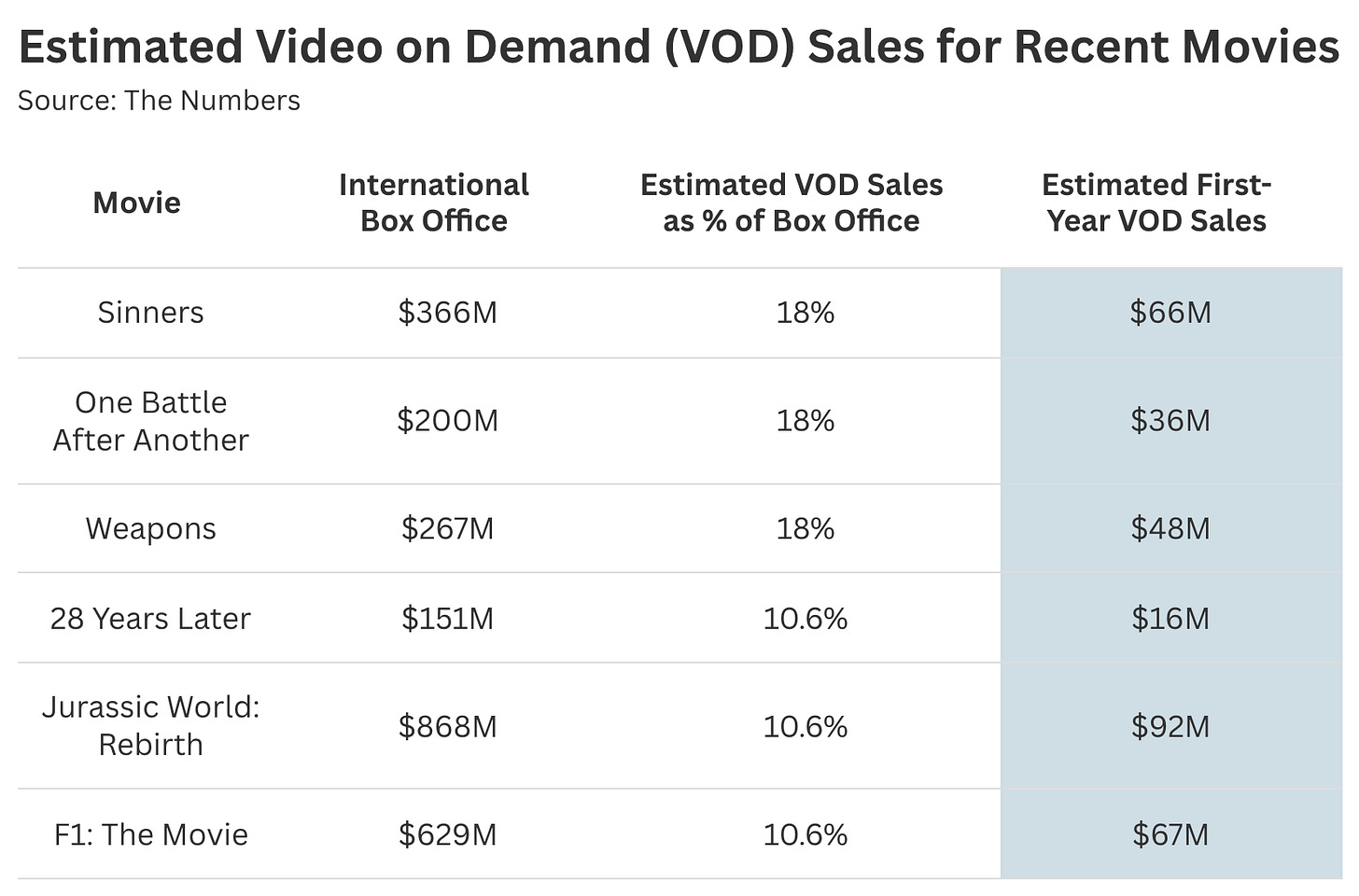

Based on the first-year VOD earnings of Wicked, Anora, M3GAN, and a handful of other titles, it appears films typically see rental sales that equal 10% to 20% of worldwide box office.

So what do these figures look like when applied to recent releases? Assuming strong buzz, a film like Sinners could see $66M in first-year VOD sales, while One Battle After Another might generate $36M in first-year rentals.

An important feature of the VOD model is that studios keep 70% of rental sales, as opposed to the typical 50/50 split for theatrical box office.

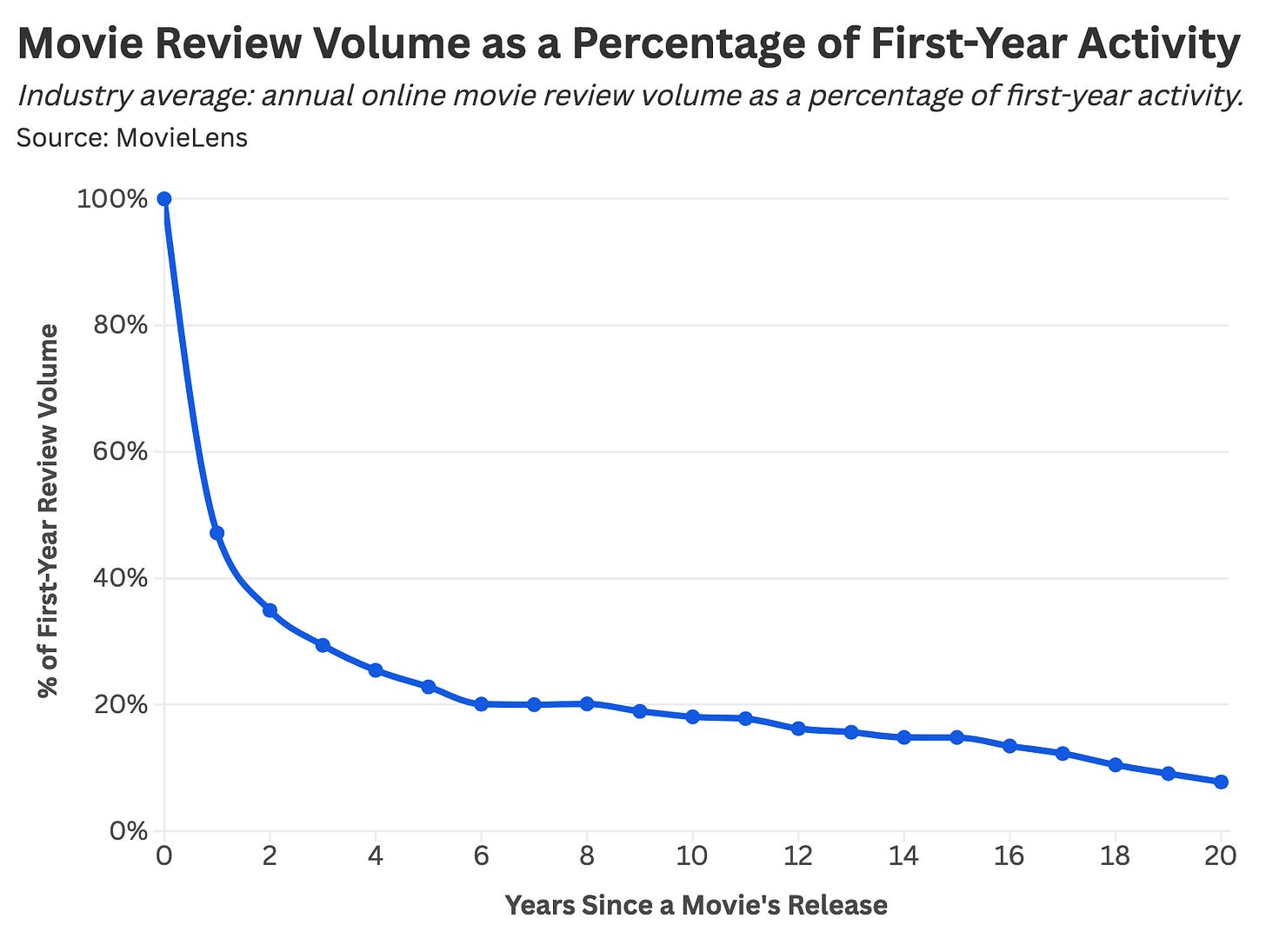

Mind you, the aforementioned figures only cover video-on-demand estimates for a film’s first few months on rental platforms. Movies don’t simply vanish after one year. Instead, film viewership follows a gradual decay curve.

User-generated data from the review site MovieLens shows that most films slowly fade from the cultural conversation, eventually settling into a steady, long-tail pattern of viewership relative to their initial peak.

What does this mean in practice? The $36M in year-one VOD rentals for One Battle After Another could dip to $7M in year two and $5M in year three, and so on.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Post-Theatrical Revenue Stream #2: Streaming Services

Most major studios are owned by parent companies that also operate a streaming service, creating a built-in pipeline between studio and streamer. Warner Bros. sends all its films to HBO Max, while Paramount routes its movies to Paramount+.

But what about movies that aren’t affiliated with Disney+ or Peacock? How do independent studios secure streaming distribution without a corporate platform of their own?

We’ll briefly outline the economics of these “streamer-less” distributors before diving into a more detailed look at studios with in-house platforms.

A Quick Overview of Streaming Economics for “Streamer-less” Studios

For the handful of major studios without in-house streaming platforms, the post-VOD revenue model revolves around bulk licensing deals with third-party platforms. For instance, HBO Max pays A24 tens of millions of dollars for exclusive access to its movie library, while Sony earns around $1 billion for its four-year output deal with Netflix. These rates are negotiated every two to five years, valuing movies as part of an amorphous content bundle.

Most studios, however, now exist within an ever-consolidating web of vertically integrated production companies and streaming platforms. In this ecosystem, assigning a discrete value to a single film has become increasingly abstract.

How Movies Make Money for Streaming Services: Where Things Get Complicated

In a digital marketplace—like a streaming platform or delivery app—understanding the value of a single product or media property is often vague, if not impossible.

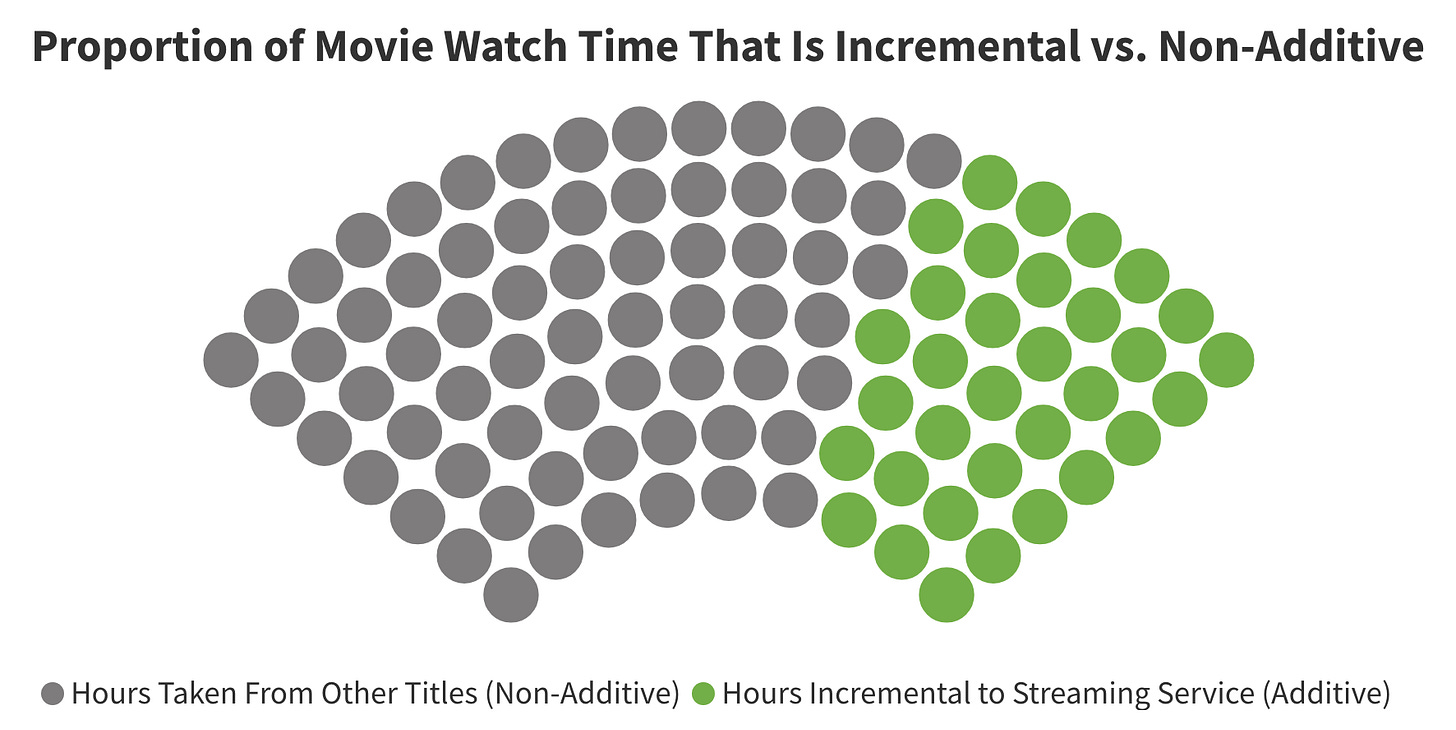

The crux of the issue can be captured with a simple thought experiment: If 100 people watch Sinners on streaming, how many of those viewers would have used the service anyway—even if Sinners weren’t available?

Viewership from users who subscribed or logged in specifically to watch Sinners is considered incremental. But if a viewer was already planning to watch something—anything—on the platform and just happened to consume Sinners, their watch time is deemed non-additive.

This split between incremental and non-additive viewership looks something like this:

Because incrementality is unknowable, services like HBO Max and Netflix struggle to pinpoint the financial impact of individual films and shows.

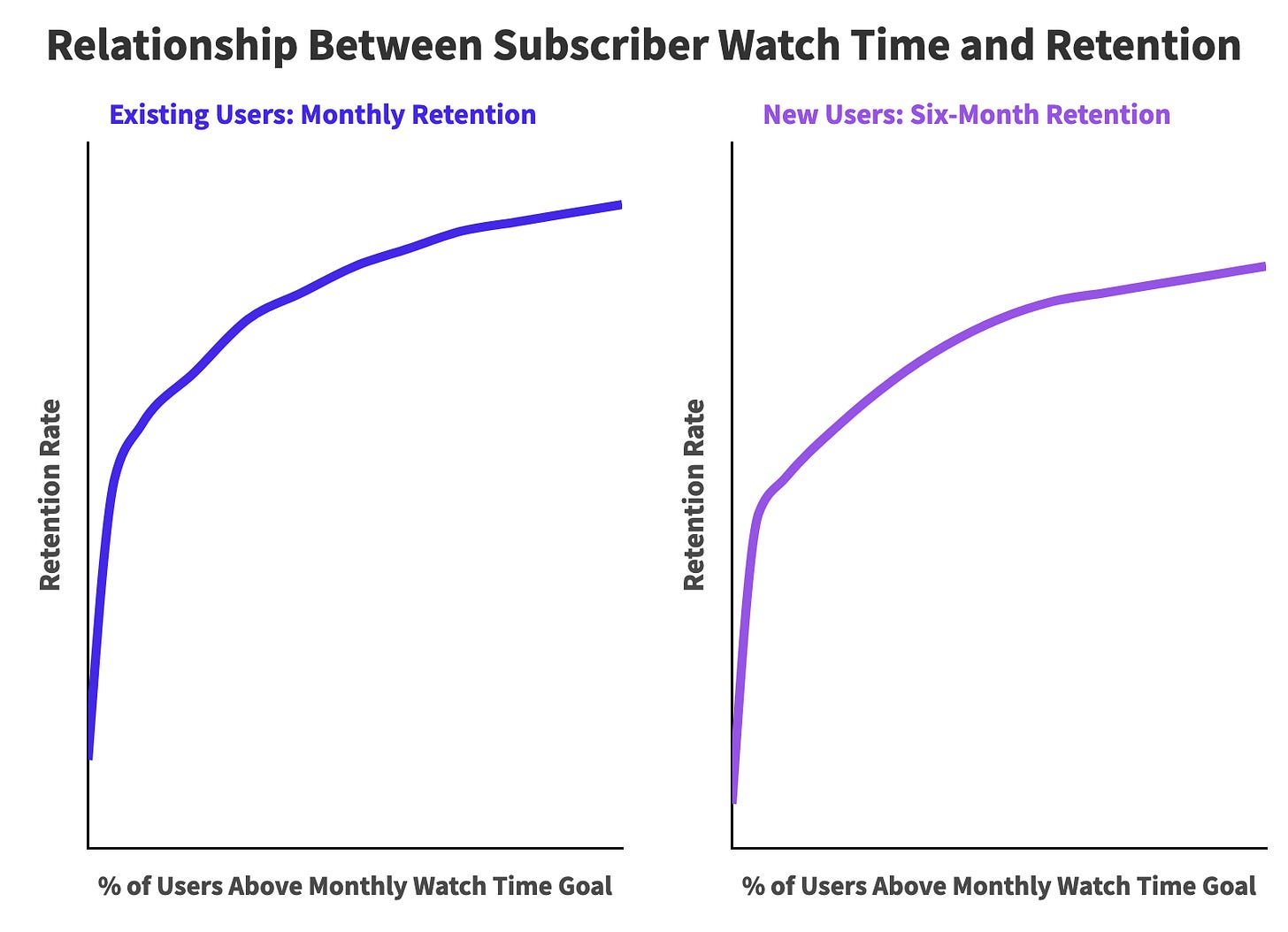

So how do streamers evaluate whether new content is actually moving the needle? To gauge programming quality, most platforms rely on a set of user engagement metrics that correlate with subscription retention (with “retention” defined as the percentage of customers who renew their membership).

Each month, streaming platforms try to nudge customers past certain usage thresholds—for example, how many customers stream 14+ hours of content in a week. The more subscribers who surpass this hours target, the better the platform’s retention: existing users stick around longer, and fewer new sign-ups cancel within their first six months.

We can imagine the relationship between usage and membership retention as follows:

If the average user is watching more, retention will rise in the months ahead, suggesting the latest batch of shows, films, live sports, and specials delivered value.

So what does all of this mean for a single movie premiering on a streaming service and later existing in its content library? Three things:

A Buzzy Movie Can Meaningfully Contribute: Hundreds of thousands of people will watch titles like Sinners, Weapons, and One Battle After Another—boosting their monthly engagement on HBO Max—and many will stick around for another month or two after watching these films, paying $18 per renewal in the process. These renewals add up to tens of millions in incremental revenue. For a large streaming service, small shifts in retention can generate an outsized financial impact.

Movies Usually Make a Short-Term Contribution: A well-regarded film like Weapons or One Battle After Another can increase platform usage in its first few months on a streaming service. Streamers understand this dynamic and promote the debut of high-profile films with splashy marketing—something along the lines of “Wicked is now on Peacock!” But after two to four months, most movies fade into the background and no longer move the needle financially. TV series, on the other hand, are more compatible with subscription economics: they keep viewers engaged for weeks at a time and, if renewed, return with new seasons that drive retention benefits across many months.

The True Value of One Movie Is Unknowable: Unlike box office sales, streaming platforms cannot attribute revenue to a single title. Usage metrics may rise or fall, but with hundreds of programs added to Netflix or Disney+ each month, it’s nearly impossible to gauge the financial contribution of any one film or series.

Post-Theatrical Revenue Stream #3: Smaller Streaming Deals and Physical Media

For completeness, I’ll quickly cover a handful of significant revenue streams that aren’t as substantial as VOD but warrant mentioning.

Physical Media Sales: DVD sales typically sit at 1% to 2% of international box office, perhaps more if it’s a critically acclaimed title and/or associated with a beloved director. This number will continue to shrink as streaming holdouts cut the cord, but that will not stop me from paying $66 for a collector’s edition box set of Donnie Darko. To which my wife said, “Why…?”

Other Streaming Deals (International, Ad-Supported, and Airlines): Most studios have licensing deals with international streaming services, airlines, and ad-supported streamers like Tubi and Pluto. These deals are negotiated in bulk, where a platform pays millions of dollars for access to a bundle of shows and movies.

Final Thoughts: The Bundle Black Box

r/boxoffice is a Reddit community where 402,000 anonymous internet citizens track the financial performance of movies in real time. This subreddit has 8x as many subscribers as r/climatechange and nearly as many followers as r/history.

Posts on r/boxoffice can be as optimistic as “I think Tron: Ares will do well and the box office will come back to life!!!” or as soulless as “Better Man made $1M yesterday. It is officially a flop.”

This message board encapsulates the horse-race mentality behind box office coverage, fixated on questions like: Which movie shattered records? Which flop confirms an actor’s epic cold streak? Is cinema so over, or so back?

Several features unique to the film industry make it well-suited to this relentless daily tracking:

Films can be analyzed individually: a movie’s box office tells its own story. Why did people see Sinners but avoid The Smashing Machine? What does the underperformance of the most recent Marvel film indicate about superhero movies?

Performance data is readily available: financial figures are published daily so that commercial appetites can be assessed in real time. Compare this to TV ratings, which exist in a walled garden created by the analytics firm Nielsen.

As someone who loves movies and stats, these numbers have always had a stranglehold on my imagination. I’m no different than the other 401,999 box office obsessives in this corner of the internet.

But over the past five years, this highly specific pastime has become increasingly outdated. A growing share of a film’s commercial performance now unfolds inside a black box. If box office tracking resembles a horse race, the final stretch now happens behind closed doors—so opaque that even the people involved aren’t sure who won.

Even more disorienting is the transition from standalone media—where each movie is evaluated as its own entity—to an ecosystem of content bundling. With each passing year, films are increasingly consumed as part of an amorphous mix of docuseries, reality TV, prestige dramas, and live sports. The value of any single title is now flattened into a $17.99 monthly subscription.

So, with all this in mind, will One Battle After Another turn a profit after going through the murky meat grinder of modern content consumption? My best guess is yes. The film will probably break even once it hits a streaming service—though what “breaking even” actually means in today’s model is anyone’s guess. If this movie were released a decade from now, its ROI would be entirely theoretical.

Movies will always straddle an ever-changing balance between art and commerce. But as streaming bundles reshape the entertainment landscape, the difficult question becomes: what happens to the art when the commercial side becomes unknowable?

Stat Significant is moving to a tip-jar model! All posts will stay free, but if you’d like to support my work, you can contribute in a few ways:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,700 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

A great article! Very informative:)

I like this explanatory format, not just asking and then answering a question.

Never give up on physical media! If Vinyl can make a comeback, anything can.