Has Music Gotten More Political? A Statistical Analysis

Has popular music become "more political"?

Intro: Not Ready to Make Nice

For a short time in the early 2000s, the country band formerly known as The Dixie Chicks found themselves at the center of pop culture for being “too political.”

In 2003, just days before the U.S. invaded Iraq, Dixie Chicks lead singer Natalie Maines told a London audience that she was “ashamed the President of the United States is from Texas.” The remark spawned massive backlash, especially from the Chicks’ core country fanbase. Radio stations banned their songs, and Fox News labeled the group “unpatriotic,” leading the band’s airplay to drop to 20% of what it had been before the controversy.

Three years later, The Dixie Chicks returned with a Grammy-winning album, headlined by the defiant lead single “Not Ready to Make Nice.” The group’s comeback was hailed as a “triumph,” though their resurgence was short-lived. Despite their Grammy success, The Dixie Chicks were blocked from country radioplay, and their efforts to cultivate a progressive pop/folk crossover audience—if such a base ever existed—failed to generate the same level of visibility. In 2020, nearly two decades removed from their anti-Bush comments, the band dropped “Dixie” from its name in response to racial justice protests across the U.S.

The Chicks may be the most prominent example of a music act “cancelled” for wading into America’s totally-awesome-and-not-at-all-exhausting Culture Wars. But was the politicization of their music—and the backlash it sparked—an anomaly? Or was the anti-Bush firestorm a sign of things to come? Has music become more socially conscious in the years between The Dixie Chicks’ rise and their eventual rebrand as The Chicks?

So today, we’ll explore whether popular music has grown “more political,” what drives the politicization of pop culture, and how lyrical content differs for Billboard-charting songs.

Has Music Gotten “More Political”?

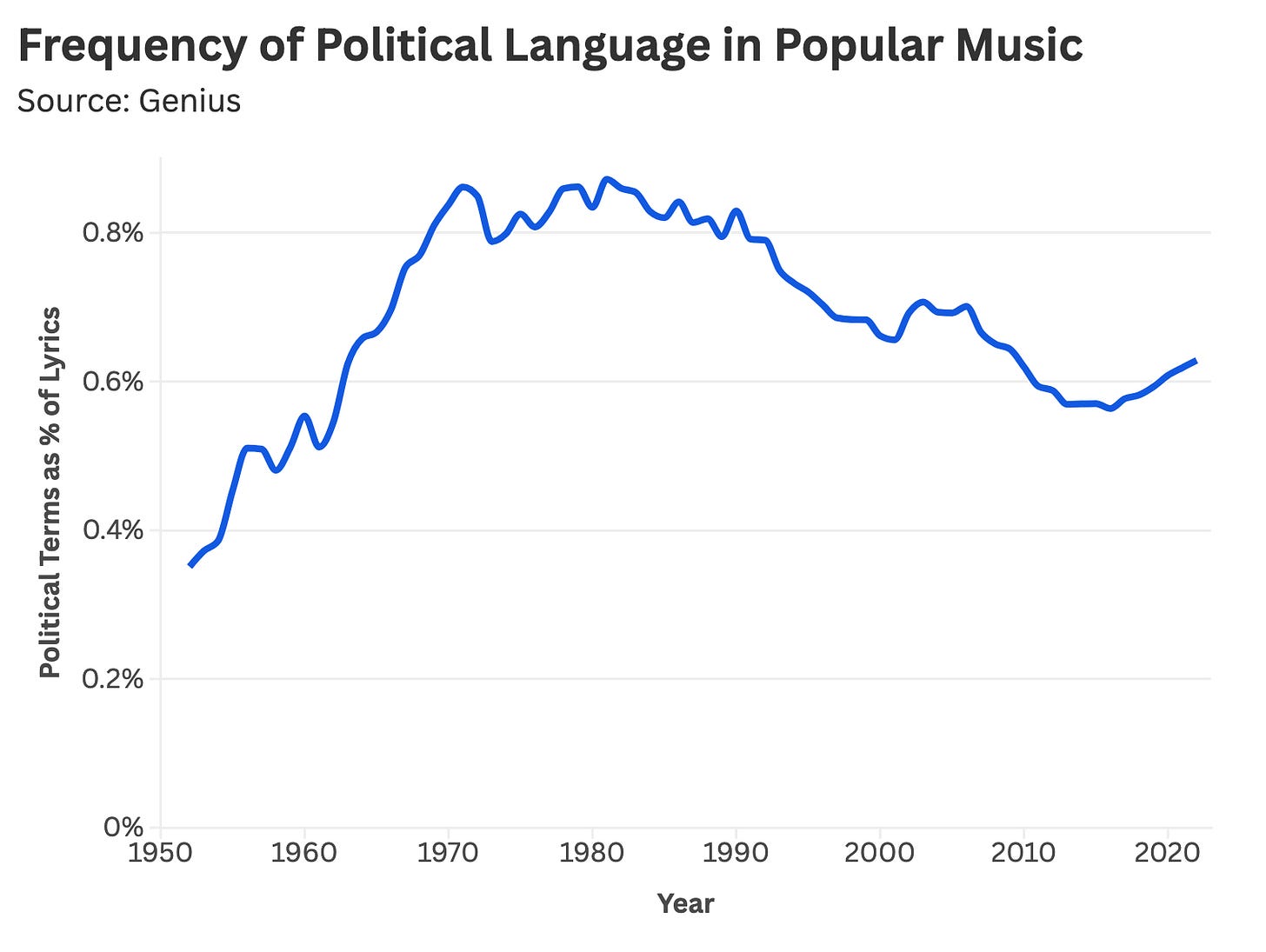

We’ll use textual frequency to measure a song’s political content. For each track, we’ll count the number of politically oriented terms, such as “justice,” “revolution,” and “equality,” and divide this figure by the total number of unique words in that song. The resulting ratio is a song’s political density.

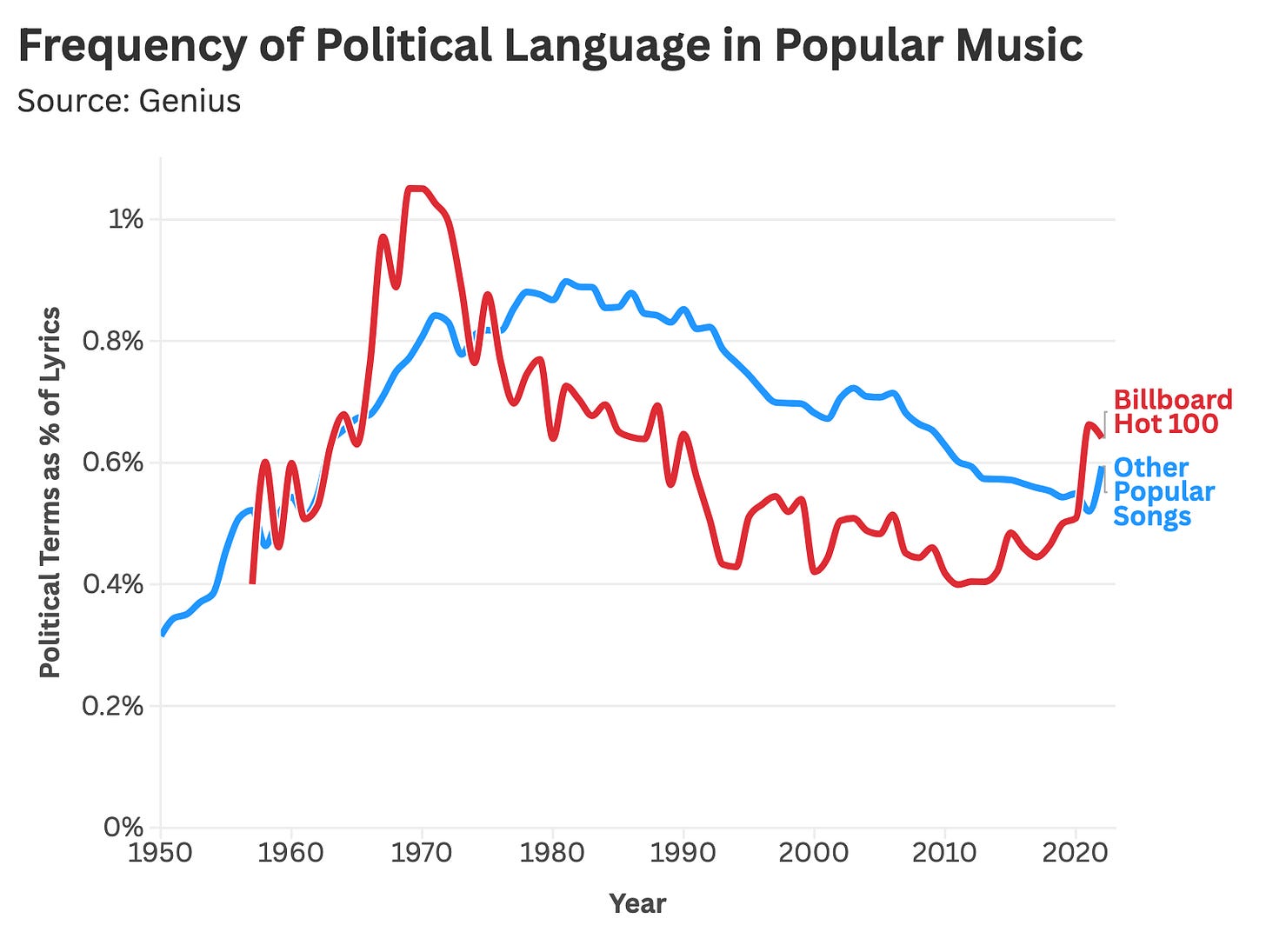

When we average our political density figure for all major record label releases since the 1950s, we find that lyric politicization peaked in the late 1970s, then steadily declined for decades before a modest resurgence in the late 2010s.

Given the sheer pervasiveness of political news today, this pattern came as a surprise. I constantly hear people grumbling about “how bad things are” and that it’s “such a bad time to bring children into the world,” and I assumed this ambient dread would be reflected in popular music. Instead, I found contemporary music to be significantly less political. So why was socially conscious songwriting more prevalent during a mid-20th-century period untouched by digital media?

For starters, this era saw a relentless stream of politically destabilizing events that shaped the cultural psyche:

The Vietnam War and the emergence of 1960s counterculture

The Civil Rights Movement, along with the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Robert F. Kennedy

The Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation

A socially conscious individual circa 1968 was also lamenting “how bad things are,” and they weren’t wrong. But “bad things” have continued happening since our observed decline in political lyricism—a global recession, 9/11, a global pandemic, Chernobyl, and multiple wars in the Middle East. So why did popular music exhibit significantly higher political engagement from 1964 to 1979—and what caused that engagement to fade in the decades that followed?

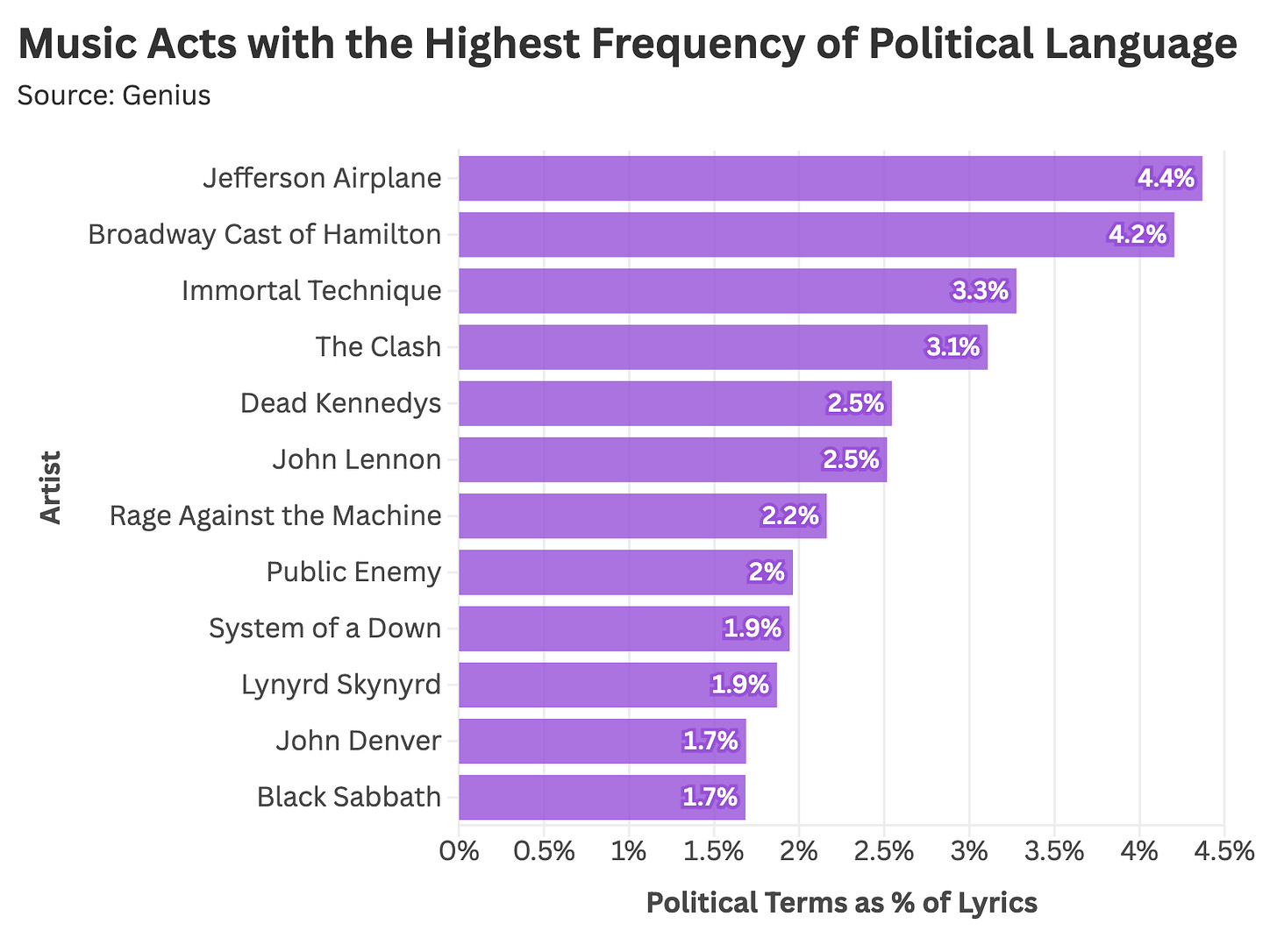

To better understand this phenomenon, we’ll examine the artists who score highest in political density—a cohort comprised of rock acts, punk groups, 1980s rap artists, and The Original Broadway Cast of Hamilton.

While the Hamilton soundtrack might read like a data error, the show’s narrative—centered on 18th-century politics and an alphabet soup of progressive ideology—makes its inclusion entirely fitting. John Lennon also feels inevitable on this list since “Imagine” may be the most politically dense song ever written. Perhaps the most striking takeaway from this group is the absence of pop artists and contemporary hip-hop, which are the most popular styles in today’s music landscape.

When we examine political lyric density among major genres, rock scores significantly higher than all other formats, while pop is the least socially oriented:

Rock: 0.74%

Country: 0.60%

Rap and Hip-Hop: 0.58%

R&B: 0.54%

Pop: 0.49%

I’ve always considered “pop” to be a functionally useless genre categorization, precisely because this term is just short for “popular.” The format hinges on a handful of vague parameters, including:

Commercial accessibility and emotional simplicity

Catchy melodies and formulaic structure

While simultaneously bearing few (or none) of the stylistic hallmarks of other genres

Pop music is often defined by what it lacks—complexity, specificity, guitar, or substantive ideology (political or otherwise). At its core, the genre thrives on escapism and spectacle.

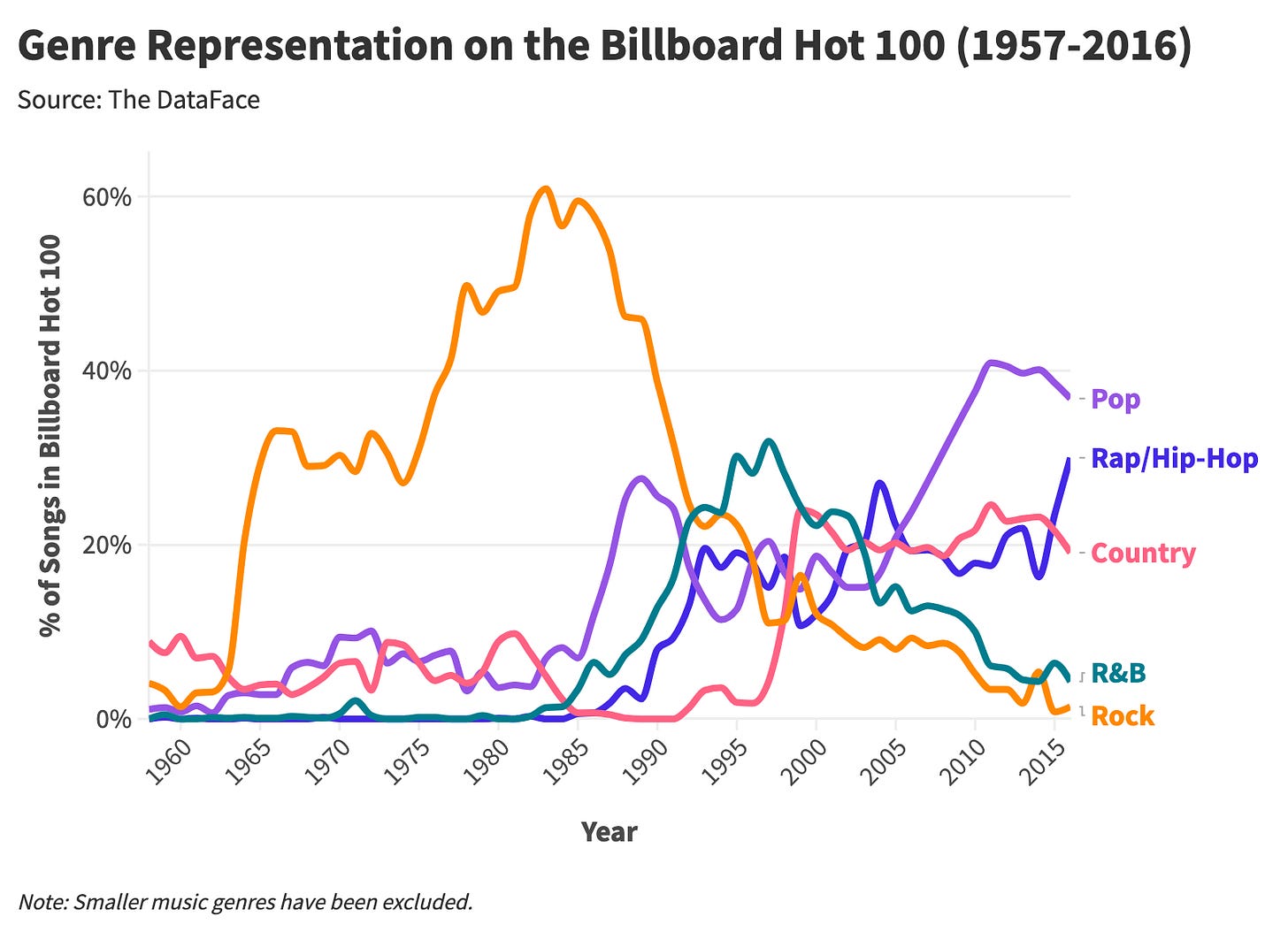

Today, this loosely defined music format dominates the mainstream. But that wasn’t always the case. In the early 1980s, rock reached its commercial peak, accounting for nearly 63% of Billboard-charting tracks, before ceding ground to pop and hip-hop—genres less focused on political themes.

While shifts in genre popularity help explain political content—or lack thereof—this single dimension does not tell the whole story.

A comparison of political lyric density between Billboard hits and non-charting tracks reveals a sharp rise in socially conscious lyrics on the Hot 100 from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, followed by a steep decline relative to other mainstream releases. Notably, this shift toward apoliticism occurred while rock was still at its commercial zenith.

The inevitable follow-up question is: What changed in the late 1970s to spark a downturn in politically charged Billboard hits? This songwriting shift can be attributed to a handful of socioeconomic trends:

Music industry consolidation: Major record labels merged or were absorbed into larger conglomerates, while radio stations were bought up and consolidated—eventually culminating in near-monopolies like Clear Channel (later rebranded as iHeartRadio). These corporate gatekeepers prioritized broad commercial appeal, favoring apolitical pop over dissension.

The rise of MTV: For nearly two decades, MTV served as a dominant tastemaker in music culture. As a cable TV channel, it operated under similar norms and standards as traditional broadcasters, favoring content that was visually engaging and advertiser-friendly. The format rewarded glam, spectacle, and accessibility—further incentivizing artists to steer clear of divisive political themes.

Post-Vietnam disillusionment and Reagan-era conservatism: In the wake of the Vietnam War and a decade of social upheaval, Western culture shifted toward conservatism. The Reagan and Thatcher years saw renewed emphasis on traditional values and consumerism. In response, mainstream music leaned into escapism and mass-market appeal. Rock splintered into commercially oriented subgenres—like glam rock and hair metal—while pop began its ascension on the Billboard charts.

These cultural shifts contributed to a growing consensus that entertainment and politics should remain separate. Audiences became more sensitive to political overtones, with overtly ideological songs or movies increasingly dismissed as “too political.”

When I was growing up in the late ‘90s, it was common to hear someone criticize a band for being overly preoccupied with politics. This critique would go something like: “I love U2’s newer stuff, but their early work was just too political for me.”

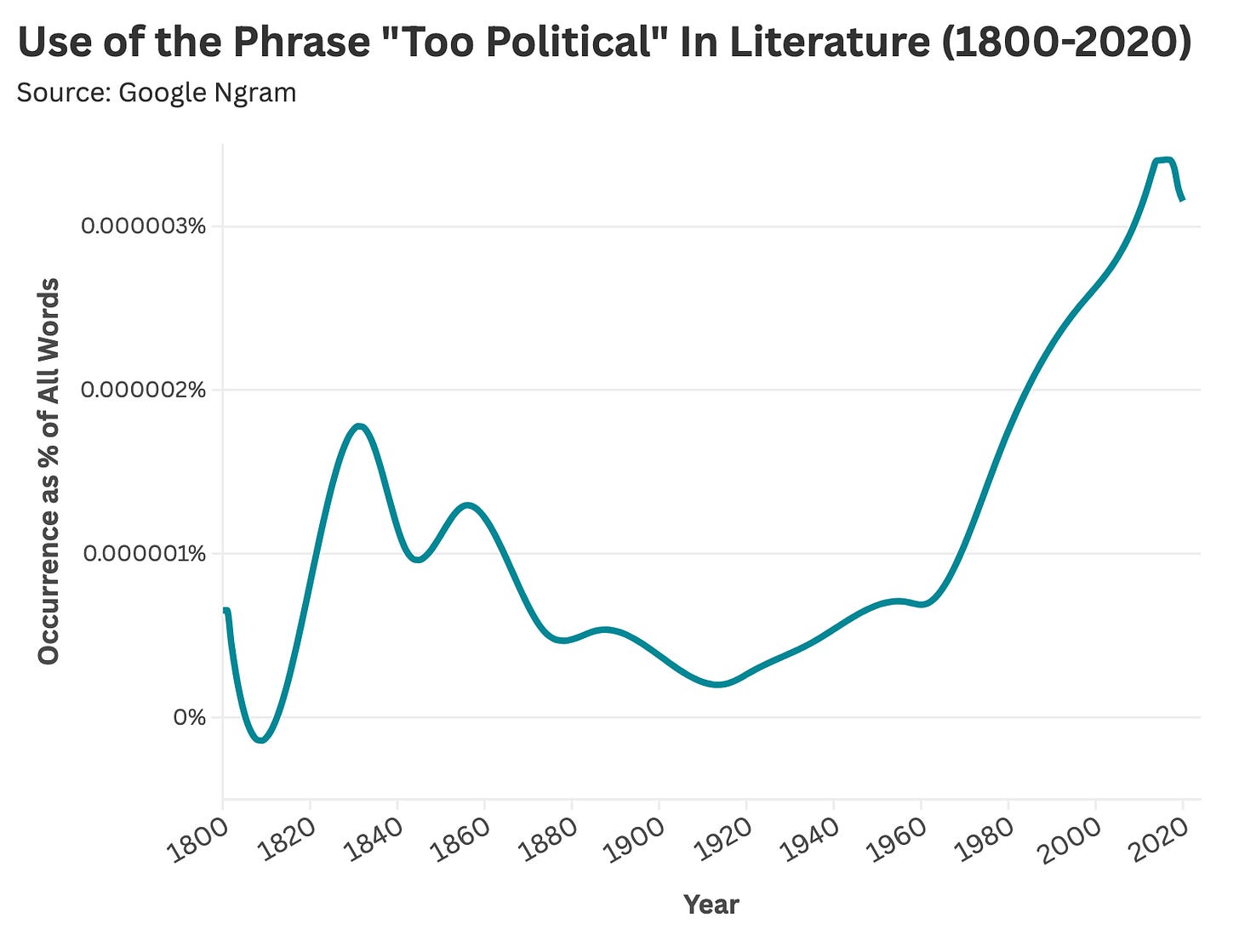

While this perceived consensus may read as abstract, its underlying sentiment can, in fact, be quantified. Google Ngram data shows a steady rise in the phrase “too political” appearing in English literature starting in the early 1960s—likely a response to the era’s political upheaval—and later peaking in the mid-2010s.

So what shifted in the 2010s? Why did this phrase see declining usage just as politically charged lyrics saw a modest uptick? My best guess is that this change can be attributed to the rise of music streaming (which diminished the effectiveness of music gatekeeping), in addition to a totally-chill-and-not-at-all-exhausting 2016 U.S. presidential election and the political schism that emerged from its not-at-all-consequential-or-polarizing result.

So yes, music has grown more political in recent years, though these levels are far from their historical peak. Whether you welcome a return to the protest songs of the late 1960s largely depends on your personal beliefs—and who, exactly, is doing the protesting.

Final Thoughts: What’s the Point?

In popular music, there’s a phenomenon known as meaning drift, where a song’s original message gradually fades—or gets reinterpreted—as the track becomes more familiar. Several once-provocative songs have experienced a political softening and/or widespread misinterpretation as a result of long-time ubiquity. Some examples include:

Born in the USA: Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” was written as a critique of America’s treatment of Vietnam War veterans and the disorientation of returning soldiers. Decades later, it’s often misread as a flag-waving anthem, appropriated by politicians like Ronald Reagan or Donald Trump during campaign rallies—much to Springsteen’s condemnation.

This Land is Your Land: Woody Guthrie wrote “This Land is Your Land” as a socialist counterpoint to “God Bless America,” spotlighting poverty, inequality, and the cost of manifest destiny. A half-century later, I learned this tune in elementary school as a cheerful patriotic sing-along—conveniently omitting the verses about starvation and the evils of private property.

Fortunate Son: Creedence Clearwater Revival’s chart-topping single was a protest against the class inequalities that determined who was sent to Vietnam. Decades later, the song is often used in military recruitment videos and patriotic montages.

Each of these examples underscores a fundamental tension at the heart of mass-distributed culture—namely, the tenuous relationship between political expression and commercialism.

Most popular music is produced, released, and distributed by companies that dislike controversy. If and when a track possesses political messaging, it must meet a Goldilocks-esque middle ground: it can be political but not too political—it has to be “just right.” This calibrated softening can open the door to vague or contradictory interpretations. And because commercially successful songs are constructed for repetition—on the radio and playlists, often across decades—they’re especially vulnerable to rearticulation, a phenomenon in which a work’s meaning drifts over time, becoming unmoored from its original context, much like “Born in the U.S.A.”

Given the unforgiving nature of today’s political climate, this phenomenon leads me to the least punk-rock question imaginable: What’s the value of a modern protest song if it risks backlash in the moment, only to have its message diluted—or, worse, completely inverted—over time? What’s the point of taking a risk if you can’t control the outcome?

The answer to this (cynical) line of questioning could go one of two ways:

More cynicism: No good comes from “being political.” It’s messy, polarizing, and frequently futile. I imagine this mindset fueled the early 2010s low point in politically conscious songwriting—artists played it safe (relatively speaking) and labels steered clear of controversy.

Practical naivete: Every action has a meaningful consequence, even if not readily apparent. Sure, these actions may prompt unexpected backlash—like the Reagan-era drift toward conservative values—but at least you did something.

Despite my natural preference for cynicism, I usually find myself siding with artistic conviction and those eager to do something. There are endless reasons not to advocate for a cause—be it meaning drift, radio boycotts, record label pressure, unknowable consequences, or social media blowback. For better or worse, or somewhere in between, the world needs artists who are willing to be “too political”—like John Lennon, The Chicks, and The Original Broadway Cast of Hamilton.

Stat Significant is moving to a tip-jar model! All posts will stay free, but if you’d like to support my work, you can contribute in a few ways:

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Have a publication or data product you’d like to advertise in Stat Significant? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

I think another factor you haven't stressed is that many top rock stars became very rich.

I think the very idea of "too political" is explicitly promulgated by the oligarchs to suppress dissent, and the same oligarchs happen to own all the means of music distribution.