Does 'Avatar' Have No Cultural Footprint? A Statistical Analysis

Investigating claims of Avatar's cultural irrelevance.

Intro: Do You Remember Anything About Avatar?

The internet loves a punching bag. Through disorganized consensus, a well-known figure (like Hayden Christensen or Forrest Gump) can become digital shorthand for a spirited grievance. Some of the internet’s most notable punching bags include:

Nickelback and Creed: these bands have become shorthand for repetitive and over-commercialized rock music.

Morbius and Madame Web: these movies have become shorthand for half-baked franchise fare.

Jar Jar Binks: this bizarre CGI creation became shorthand for everything wrong with George Lucas’ Star Wars prequels and the legacy-killing potential of reboots.

And, in recent years, James Cameron’s Avatar has become internet shorthand for hollow commercialism—an ephemeral pop artifact that made a lot of money and (allegedly) disappeared. The internet discourse surrounding Avatar is coded with disbelief and deception, as if the moviegoing public was the victim of a long con (where we all wore 3D glasses and watched a film starring “Sam Worthington”).

Years after the first Avatar’s release, Forbes declared, “Five Years Ago, Avatar Grossed $2.7 Billion but Left No Pop Culture Footprint,” and The New York Times wrote an in-depth essay on “Avatar and the Mystery of the Vanishing Blockbuster.” In 2016, Buzzfeed created a quiz entitled “Do You Remember Anything at All About Avatar?” that challenged readers to recall basic details like the lead character’s name (Jake Sully) or the actor who played Jake Sully (“Sam Worthington”). Somehow, Avatar’s commercial success has not translated into cultural longevity, according to internet punditry.

How can a movie make over $2B and, subsequently, be deemed culturally irrelevant? Are these claims legitimate, or is the internet dogpiling on a commercial success?

So today, we’ll quantify the cultural afterlife of James Cameron’s Avatar franchise, attempting to make sense of its perceived irrelevance. We’ll investigate various markers of cultural significance in the digital age and the idiosyncrasies that separate Avatar from run-of-the-mill franchise entertainment.

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by The Stat Significant Dataset Hub

Access 160+ Curated Datasets to Elevate Your Analysis

Want the data behind the deep dives? The Stat Significant Data Hub gives you access to 160+ curated datasets spanning movies, music, TV, economics, and more.

New datasets are added weekly, with full archive access for Stat Significant paid subscribers. Since last week’s post, we added 11 new datasets—covering everything from songwriting credits to Bigfoot sightings.

Do People Care About Avatar a Decade Later?

Director James Cameron (often referred to as “Big Jim”) simply does not miss. This man has repeatedly helmed “the most expensive movie ever made,” to the media’s dismay, and has subsequently produced “the highest-grossing movie of all time.” Cameron’s filmography is remarkable: Titanic, Avatar, Aliens, Terminator 1 & 2, True Lies, and The Abyss. I really cannot stress how good this guy is at making movies and money (at the same time).

Cameron first announced his plans for Avatar in the mid-90s before he finished work on Titanic. The Avatar project would go on to a decade’s worth of production delays, leading to intense media fascination, numerous internet leaks, and ever-escalating hype:

Cameron contracted a linguistics consultant from USC to develop a Na’via language for the film, marked by a dictionary of over 2,500 words.

Avatar enlisted a team of botanists to consult on the creation of fictional flora for the imagined world of Pandora.

Avatar was estimated to be “the most expensive film of all time,” with a budget between $250M and $500M.

As usual, the press framed Cameron’s passion project as Hollywood bloat—a decades-long disaster in the making. As usual, they were wrong because Big Jim simply doesn’t miss. In this case, Jim Cameron did not miss to the tune of $2.8B in global box office and nine Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture). 20th Century Fox (now Disney) promptly greenlit two sequels, and just like that, Avatar went into hibernation—not to reappear for 13 years (like those weird cicadas).

It’s during this 13-year gap that claims of the movie’s nonexistent cultural footprint began appearing across the web. Yet Avatar’s perceived insignificance is far from straightforward.

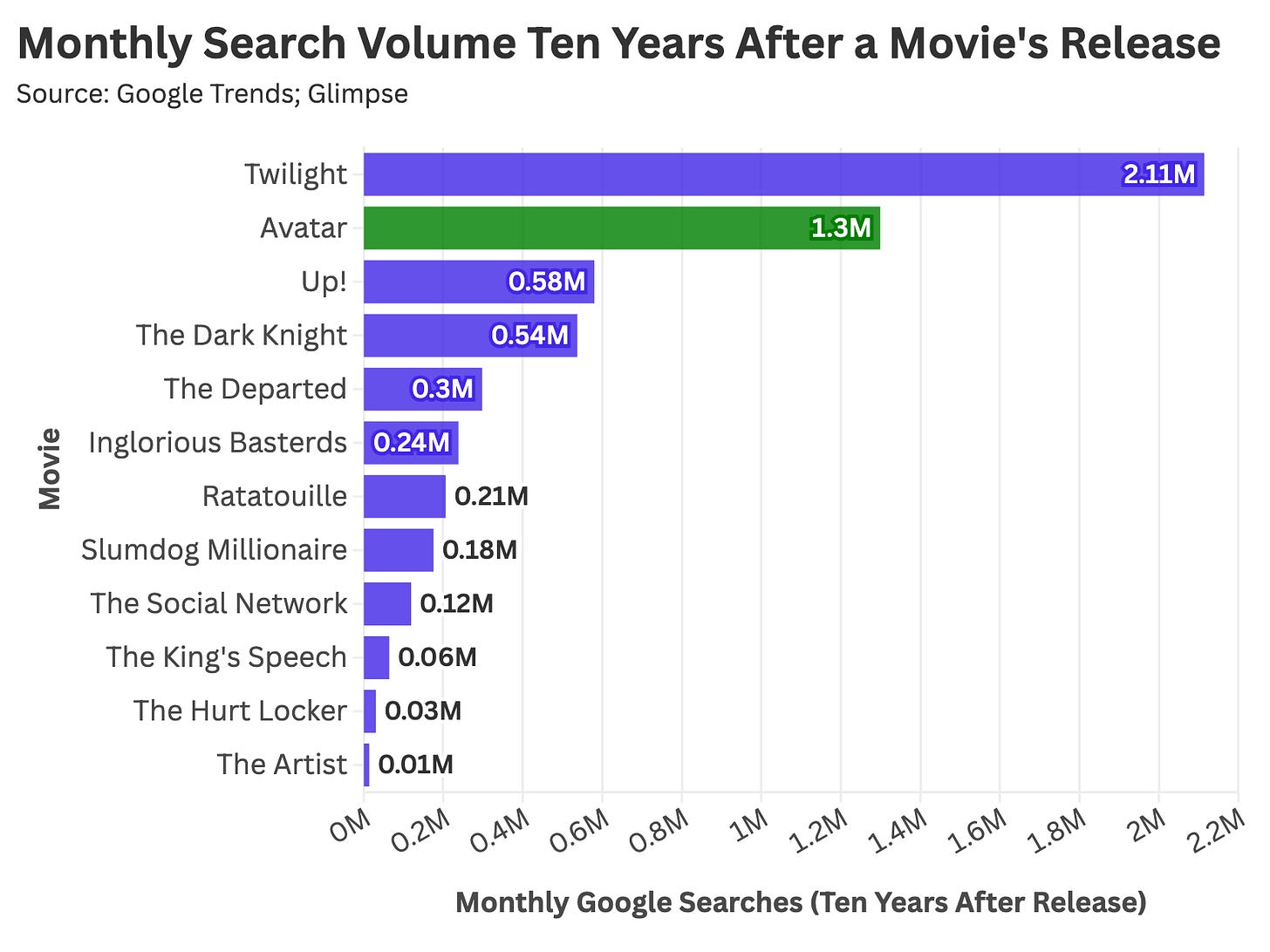

Using a tool called Glimpse, we can compare search volume for Avatar and other films in the ten-year period following their release. The logic here is simple: if people cared about these movies a decade after their debut, they would Google them (for various reasons).

When we compare query volumes for early-2000s blockbusters (Twilight, Up!, The Dark Knight) and Oscar winners (The King’s Speech, The Hurt Locker, The Artist), Avatar emerges as the second most-searched film of the group.

At the same time, absolute query volumes only tell part of the story. Claims of Avatar’s insignificance are conditional—focusing on the movie’s footprint relative to its $2.8B in box office. According to this line of thinking, the movie’s commercial capital has not translated into longstanding cultural capital.

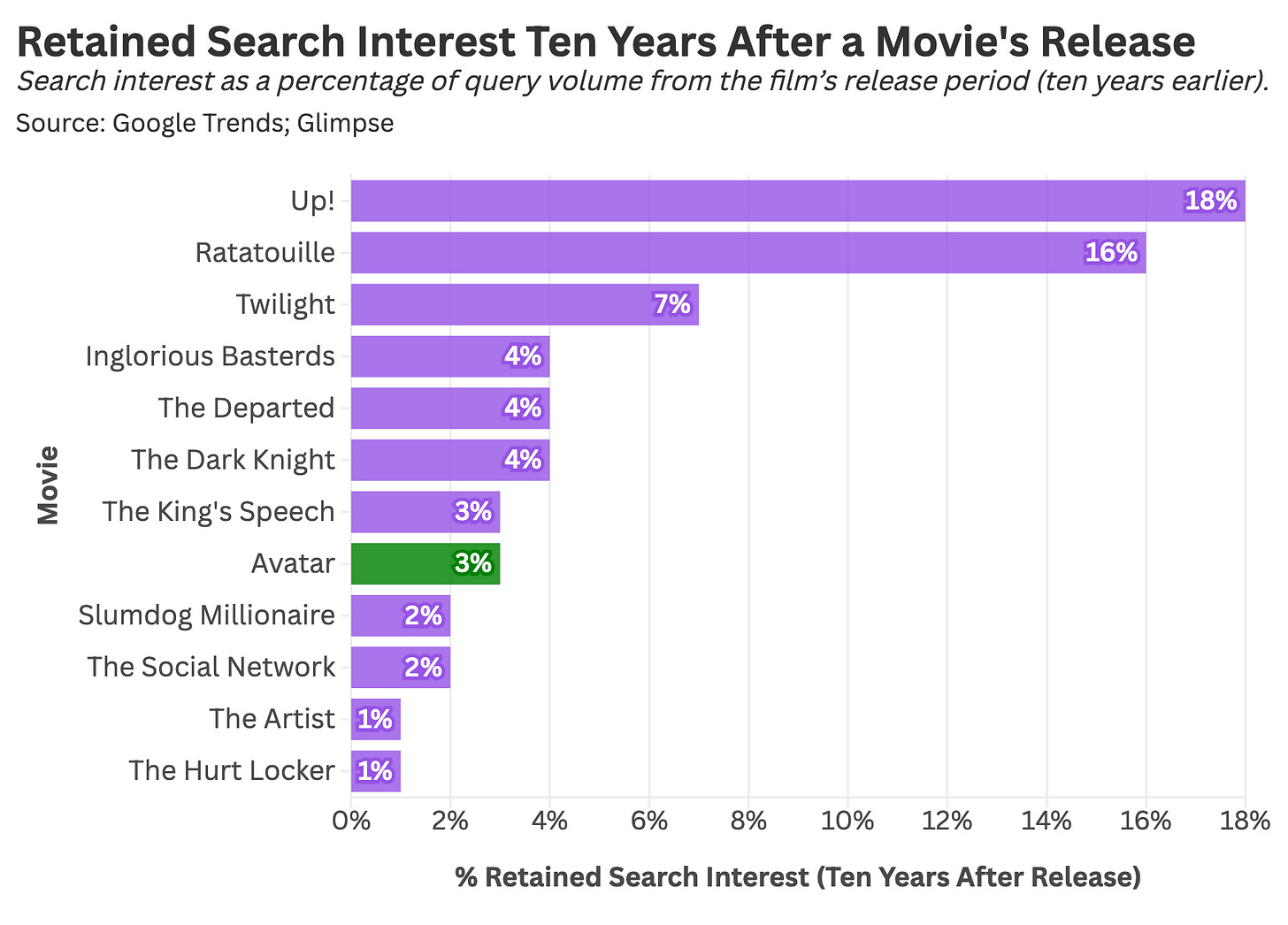

These claims maintain some legitimacy when we examine the relative decline in search interest for Avatar against this same set of movies.

We’ll use retained search interest to track this downturn, a metric calculated as follows:

Search Volume Upon Release: Let’s say a movie had 100 searches the month of its release.

Search Volume a Decade Later: Let’s also say that this same movie had 4 searches a decade later.

Retained Search Interest (A Decade Later): This movie’s retained search volume would be 4%.

According to this figure, Avatar lost a significant share of its search volume relative to the commotion surrounding its debut. By this metric, its long-term hold on popular imagination is inconsistent with its initial hype.

Given this decline in search interest, it’s tempting to conclude that Avatar has faded from cultural memory—a $2B delusion ($5B total if you count its sequel). But this regression prompts a more intriguing question: How does a film watched by over 20% of American adults struggle to leave a lasting mark on collective imagination?

How and Why Did Avatar Fade From the Zeitgeist?

Most big-budget movies are built around fandoms, expressly crafted to cultivate an ever-growing mass of die-hards through successive installments and reinvention of the familiar. With each episodic release, a franchise like Planet of the Apes or Fast & Furious expands its footprint, adding to its lore and feeding its fans cultural comfort food.

Cameron’s never-ending passion project defies several hallmarks of franchise world-building, avoiding brand extensions that cultivate fandom: there are few Avatar toys, no supplemental literature for fans, no Avatar TV shows, few mass-produced Avatar props or costumes, and minimal Comic-Con presence. Avatar does have its own section of Disney World, and that’s about it (even then, how many people are going to Disney World for Avatar?). Unlike other billion-dollar franchises, Avatar eschews fan service, resulting in a smaller fanbase and a reduced digital presence.

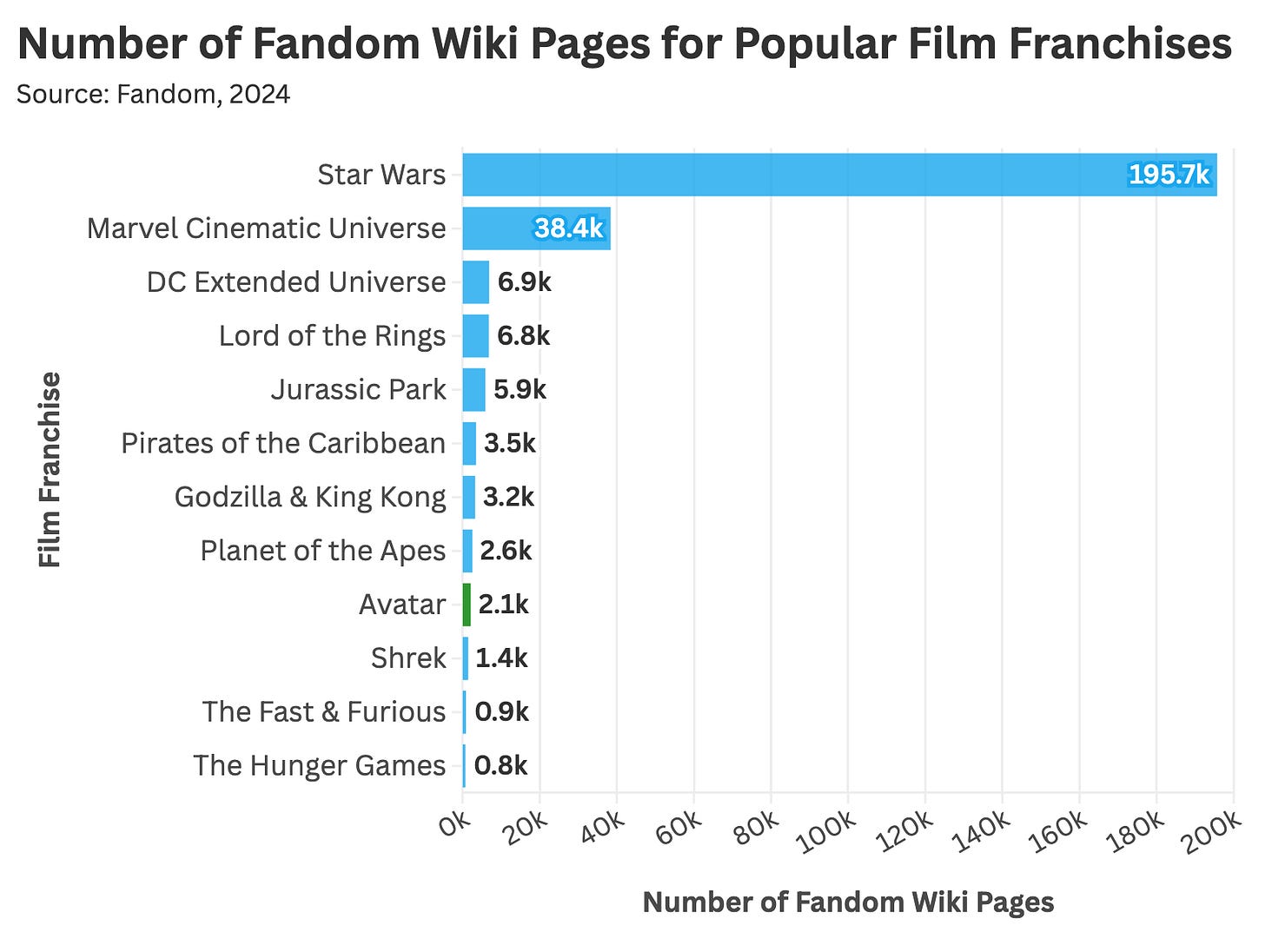

To quantify the film’s digital footprint, we’ll turn to Fandom, a website dedicated to building wikis for television shows, movies, and other beloved fictional universes (essentially, Wikipedia for pop culture). Within a given wiki sits hundreds of pages—character overviews, plot breakdowns, explanations of mythology, and so on—all fan-produced.

Avatar has a relatively small presence on Fandom compared to other multi-billion-dollar films, with fewer pages in its wiki repository.

At first glance, this makes sense—there have been only two Avatar movies released 13 years apart. Rather than rush Avatar 2 to capitalize on its predecessor’s success, Big Jim took his time, a departure from the strict franchise playbook that dominates contemporary Hollywood.

But Avatar’s diminished legacy goes beyond release frequency. Over its 16-year history, Cameron’s franchise has been largely overlooked by most pockets of internet culture. Consider the film’s meme presence, and by this, I mean pictures with text that use Avatar imagery.

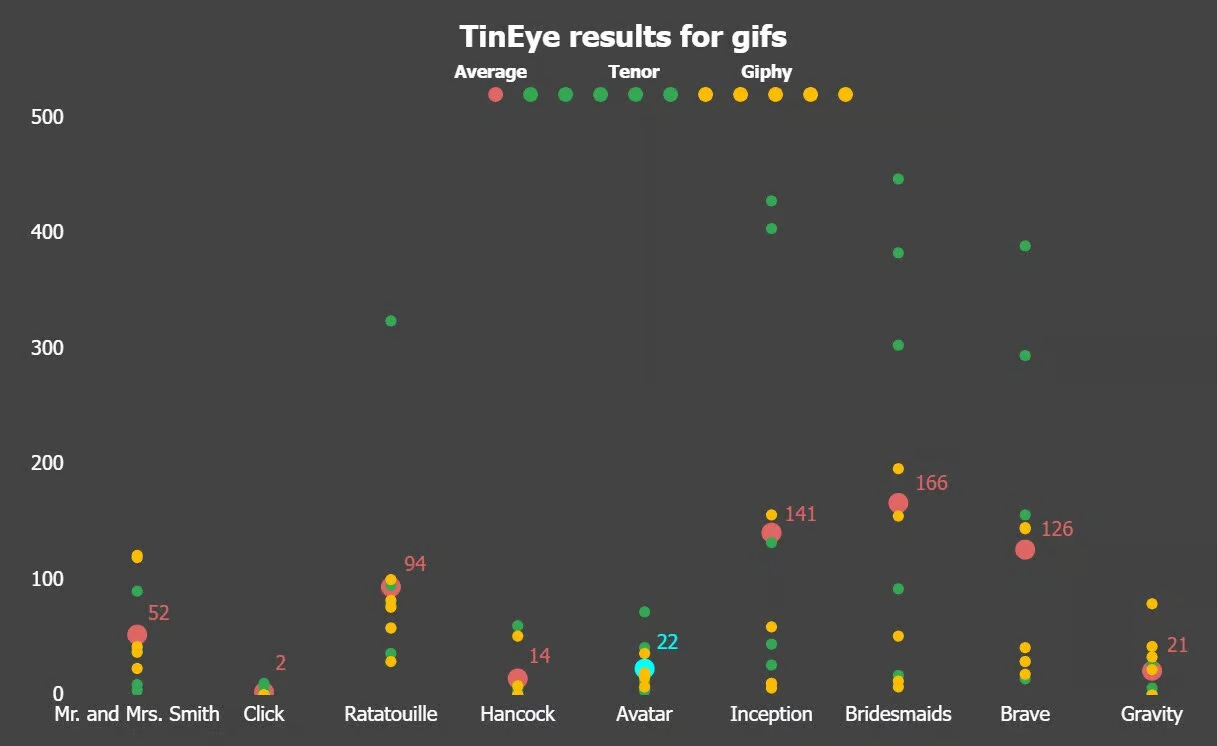

In his analysis of the franchise’s “cultural weirdness,” internet researcher Adam Bumas compiled data on Avatar meme activity, comparing its use as source material to other blockbusters from the 2000s and 2010s. In the chart below, each dot represents a meme, and the associated counts represent the prevalence of these memes according to platforms like Giphy and Tenor. According to these figures, Avatar has a significantly smaller meme footprint than other commercial successes.

Is meme activity a perfect encapsulation of cultural legacy? Of course not. Memes can, however, signify a movie’s hold over popular imagination. Leonardo DiCaprio’s squinting face from Inception is an enduring image from a movie laden with dense, overly complex dialogue. Someone remembered Leo’s squinty-ness and thought to make it a meme, and through internet consensus surrounding this moment’s meme-worthy-ness, the image was embraced.

Personally, I don’t remember any one moment from Avatar other than the characters professing their love for a tree and bonding their hair to one another. I find neither of these sequences to be meme-worthy. In fact, the main thing I remember about Avatar is the experience of watching the movie (rather than what I saw on screen).

And this leads me to perhaps the most crucial facet of Avatar’s ephemeral relevance—the project’s all-consuming emphasis on theatricality. Avatar and its sequel were marketed as can’t-miss theatrical events. You had to see these films on the big screen while wearing 3D glasses to get the full experience. It’s difficult for a movie to generate meme-worthy content when it doesn’t lend itself to rewatchability.

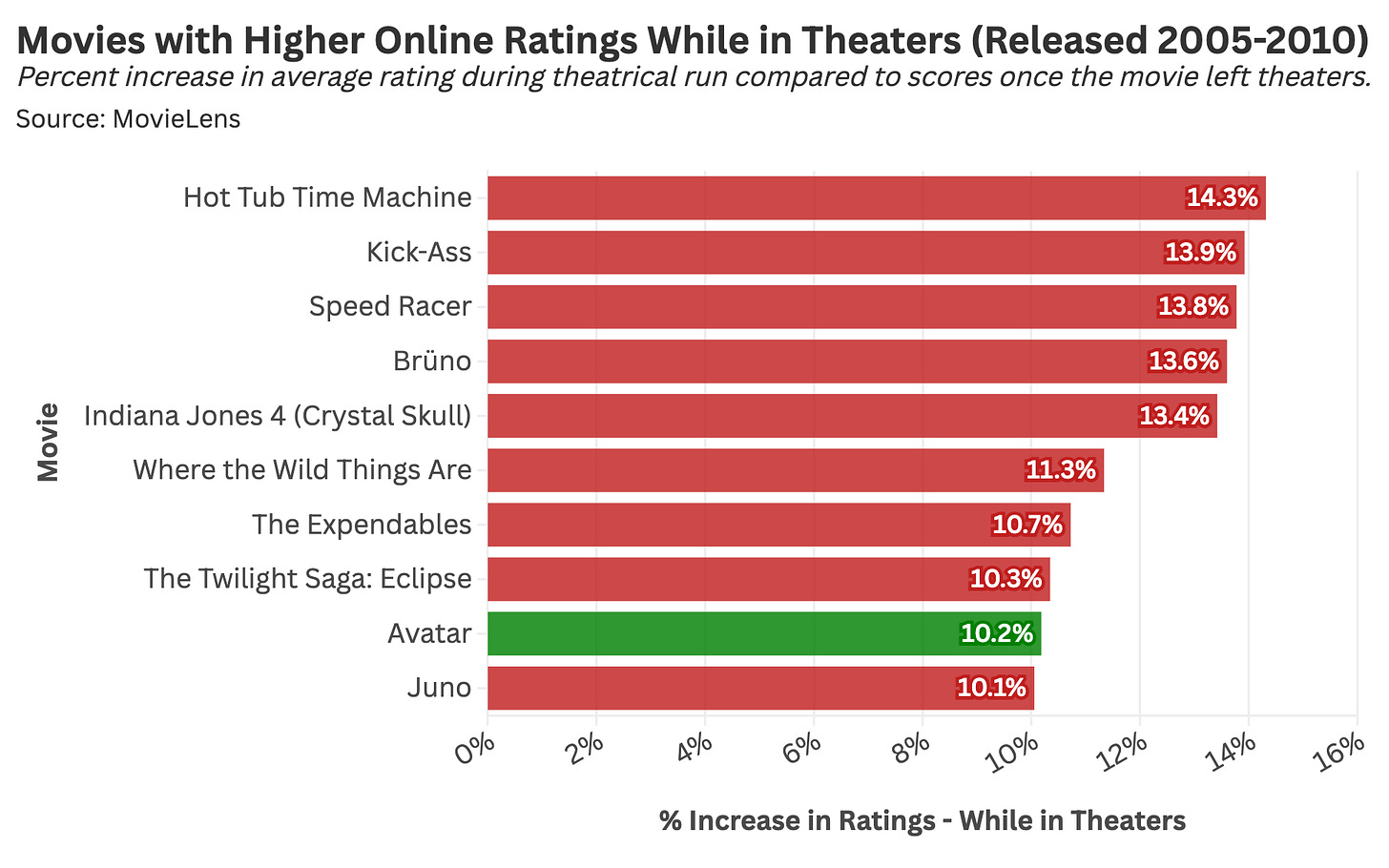

To measure the difference between theatrical and at-home enjoyment, we’ll compare average MovieLens user ratings recorded during a film’s theatrical window with ratings submitted after it went to home video. When we apply this methodology to films released between 2005 and 2010, Avatar emerges as one of the clearest examples of a film that works better in theaters.

In my opinion, this is the crux of Avatar’s asymmetric cultural impact: it was an event explicitly produced for movie theaters. Central to its marketing was the notion that the film’s entertainment value was significantly reduced when experienced at home.

Avatar and its sequel are the antithesis of most modern entertainment products—optimally designed for the big screen, scarcely merchandized, and ill-suited for consumption via Peacock.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: Why Do We Make This So Complicated?

Three years ago, I went to see Avatar: The Way of Water just like everybody else. Like most people, I had forgotten what I liked about the original apart from a vague understanding that it looked really cool on the big screen, which was enough to warrant a $20 ticket purchase.

As I walked into the theater, someone attempted to hand me a pair of 3D glasses—to my great shock. Somehow, I had completely forgotten that Avatar (the most commercially successful film of all time) was a 3D movie meant to be a trailblazer for the entertainment industry’s (then-imminent) shift to 3D exhibition.

It was at this moment that Avatar‘s fleeting relevance came into focus: of course a film that warrants 3D glasses for state-of-the-art viewing is going to be significantly less popular once it exits theaters. Why was this so difficult to understand? The experience of seeing Avatar is entirely self-contained: you go to theaters, you get your 3D glasses, you watch a Nicole Kidman AMC ad, you go back to Pandora, reacquaint yourself with totally real Hollywood actor “Sam Worthington,” see some spectacular visuals, and then you go home excited to see the next installment in three to thirteen years. Why was this movie’s appeal so widely misunderstood?

Perhaps this grievance stems from misplaced expectations. Avatar debuted in 2009, just a year after Iron Man, the first official installment of Marvel’s Cinematic Universe (MCU). James Cameron did not design Avatar to be intellectual property that sucks every last dollar from its fandom, yet we judge the series by standards set by the MCU (which is odd, since the MCU is presently falling out of fashion).

Over the past two decades, we’ve grown accustomed to the excessive fan service that accompanies mainstream entertainment products: a franchise installment every year, a world-expanding TV series, limitless merch, casting rumors, Comic-Con trailers, co-branded Lego sets, and stories that are mostly the same but add a dash of novelty (i.e., a new actor plays Spider-Man but Uncle Ben still dies). We’re given films that serve little purpose beyond sustaining their own existence and generating future monetization opportunities—artifacts of corporate strategy that keep a fandom flywheel moving.

Fortunately, Big Jim does not care about any of these things (and fortunately, Big Jim does not miss).

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

When we talk about “reach,” we usually collapse different things into one word. Henry Jenkins would say that’s the mistake. Reach isn’t just how many people paid or how big the opening weekend was — it’s about circulation and reuse.

Avatar has enormous broadcast reach and experiential impact: millions of people saw it, felt it, and moved on. But it has very little participatory reach. It doesn’t generate language, gestures, memes, or practices people can easily pick up and use. It’s sticky, not spreadable.

Cult films like Paris Is Burning are the opposite. Almost no economic reach, but massive semiotic reach. People quote it, perform it, borrow its language, build identities with it. It survives because audiences keep doing things with it.

So the issue isn’t that Avatar has “no cultural impact.” It’s that we’ve been trained to equate impact with constant participation. Avatar is a mass ritual you experience and leave. Paris Is Burning is a toolkit you carry forward. Different kinds of reach, different afterlives.

I remember being surprised when I first found out that Avatar was the highest grossing movie of all time, given how little anyone ever talked about it, but after the Way of Water came out and I went to watch it in theaters, the reason was pretty obvious, and it's exactly what you say here. Of course a movie whose primary appeal is how amazing the visuals are is going to do well in theaters, where you get the visuals in their full glory, but then have a significantly reduced cultural impact afterwards, since no one can see it in theaters anymore.

I have one criticism of your statistical analysis, though: Google searches for "Avatar" are a bad way to gauge the lingering cultural impact of the movie, since the search can refer to a bunch of other things, including a totally separate popular franchise. Such is the nature of movies with a one-word title.