Do Music Stars Write Their Own Songs? A Statistical Analysis

Do pop stars write their own hits—and if not, who does?

Intro: The Hit Factory

In the early 1960s, popular music ran through the Brill Building. This innocuous structure in Midtown Manhattan was a hit factory where songwriters like Carole King, Gerry Goffin, and Neil Sedaka penned dozens of Billboard-charting songs, including “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “I’m a Believer,” and “On Broadway.” The Brill Building’s mechanization of songwriting mirrored an assembly-line system, with producers pairing lyricists, composers, arrangers, and vocal groups to produce commercially oriented singles. Artists like The Drifters, The Monkees, and The Shirelles topped the Billboard charts with tracks written and arranged by an assemblage of then-anonymous Brill Building staff. This model of music production emphasized systematization over the talent of any one star.

And then as quickly as the Brill Building overtook Top 40, it receded. This sudden decline can be traced, in part, to a group of mop-topped Liverpudlians—The Beatles.

The Beatles and other mid-century rock bands popularized writing and performing their own material, diminishing the appeal of outsourced song production. By the early 1970s, the Brill Building machine and similar outfits had largely died out as the industry shifted toward artist-written albums.

In the five decades since the Brill Building’s decline, popular music has continued to evolve at breakneck speed. Genres have come and gone (Disco, Ska, Punk), streaming has upended monetization and discovery, and the very notion of pop stardom has shifted dramatically. So how has music authorship adapted to this constantly changing landscape? Do today’s chart-topping artists write their own material, or has a Brill Building–style system quietly replaced the rockist ethos popularized by The Beatles?

So today, we’ll explore 70 years of songwriting trends, examine a burgeoning model of music authorship, and evaluate how song production varies across different forms of music stardom.

Do Music Stars Write Their Own Songs?

In his book Uncharted Territory, Chris Dalla Riva traces the history of popular music through works that have topped the Billboard charts. To do this, Dalla Riva compiled an extensive dataset cataloging every No. 1 hit and key attributes related to the composition, content, and authorship of these tracks. Most relevant to today’s analysis, the dataset includes detailed songwriting credits and each artist’s involvement in producing a track.

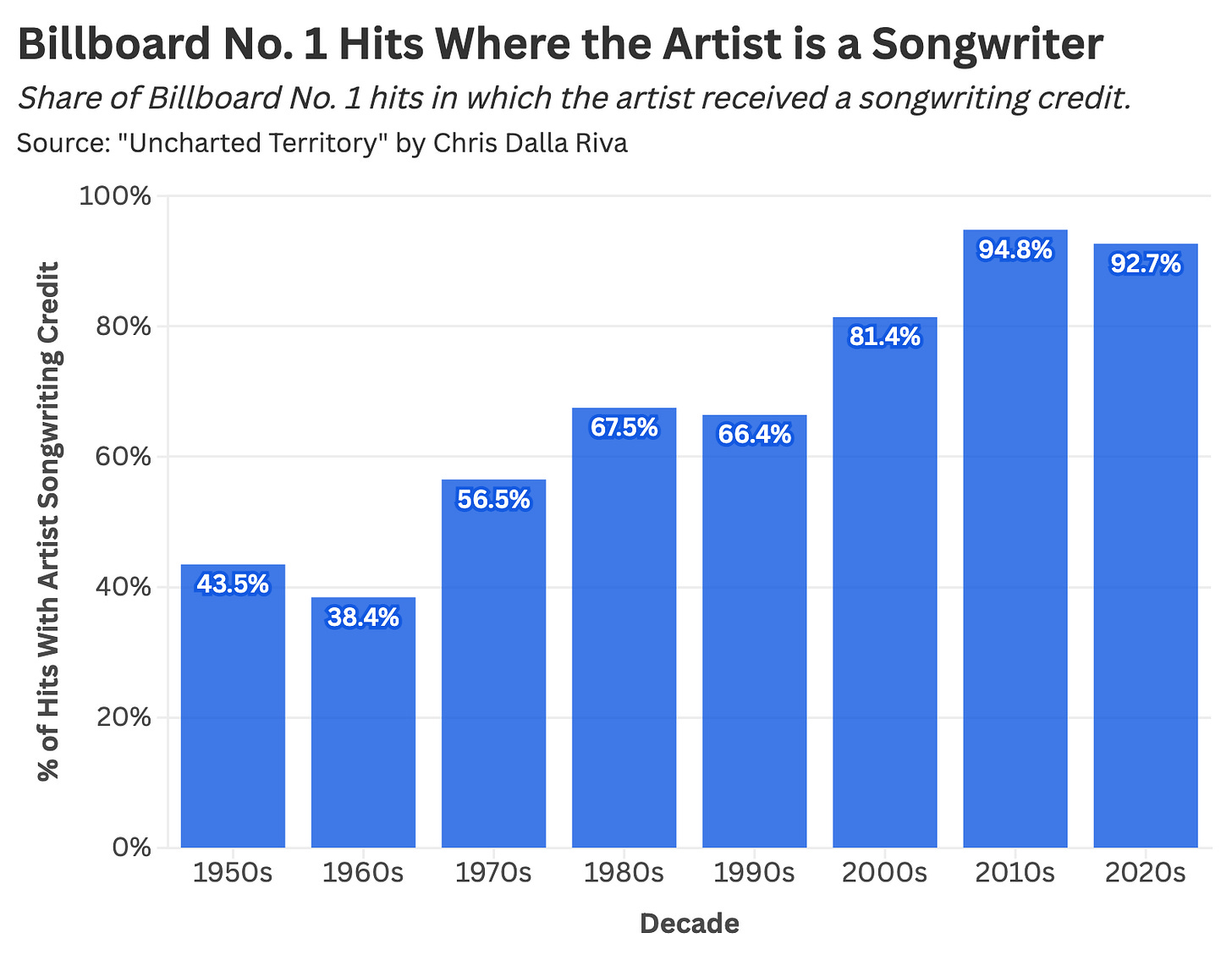

When we examine how often chart-topping artists contribute to their own songs—and thus earn songwriting credits—we see a steady rise in authorship that now approaches 100%.

I expected this figure to increase after The Beatles’ rise and the Brill Building’s obsolescence, and then assumed this trend would peak (and later level off) somewhere in the latter half of the 20th century. So how is artist songwriting involvement higher today than it was during rock’s commercial peak in the 1970s and ‘80s?

The answer hinges on how writing credits are assigned and how one evaluates authentic artistry.

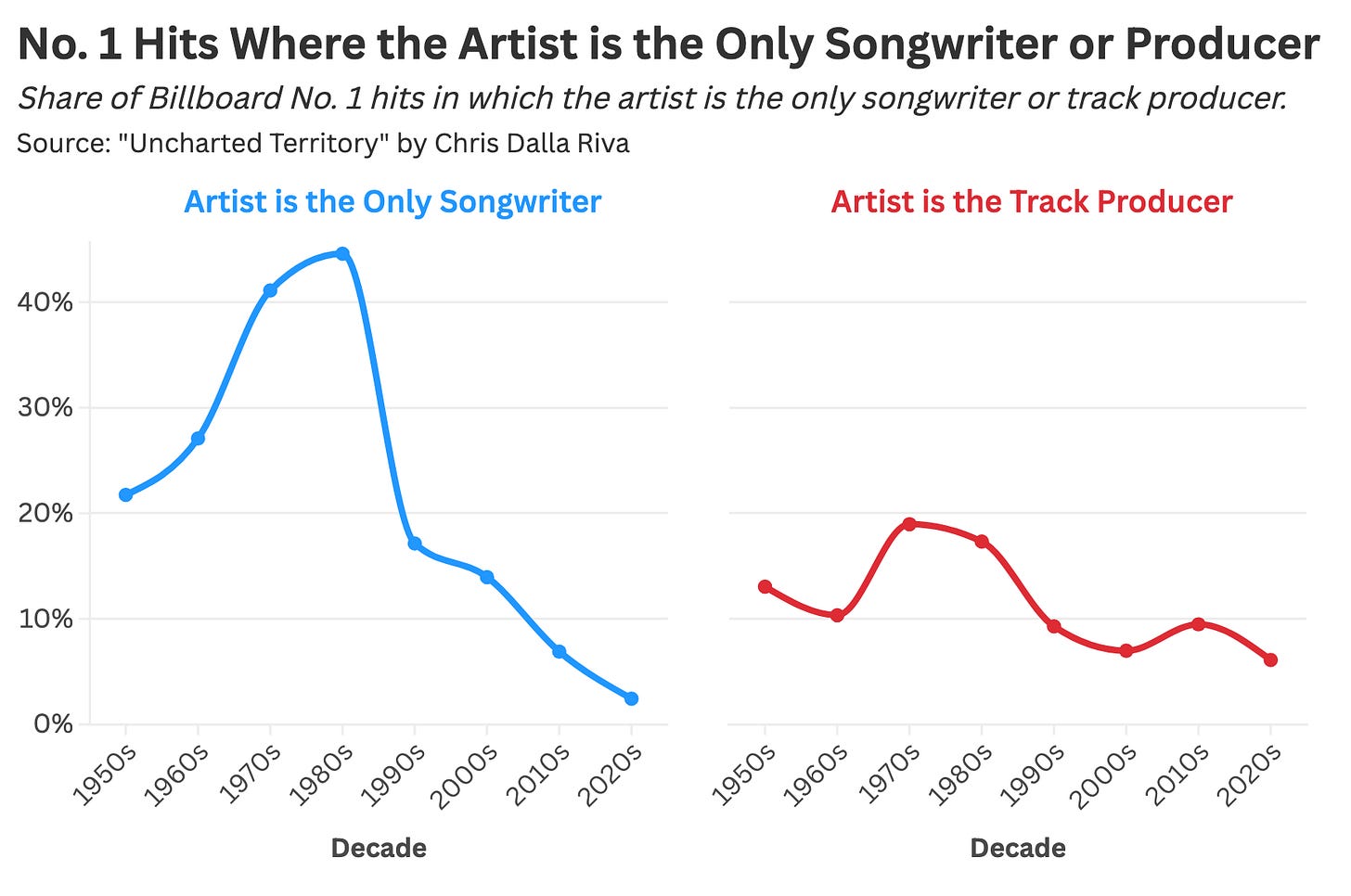

Beyond initial songwriting credits, our dataset also flags when an artist is the sole songwriter or producer on a track—an occurrence that peaked during rock’s commercial apex and declined as the genre receded from the mainstream.

So what explains a rise in songwriting credits for pop stars alongside a simultaneous decline in solo authorship and producing? This curious shift reflects what I’ll call the Max-Martin-ification of Top 40.

Who is Max Martin, you ask? A prolific Swedish songwriter-producer whose invisible handiwork has delivered chart-topping hits for Britney Spears, The Backstreet Boys, Kelly Clarkson, Taylor Swift, The Weeknd, and many others. His quiet dominance reflects the rise of the anonymous-guru-hitmaker with impeccable commercial instincts.

Scan the songwriting credits for recent Taylor Swift or Sabrina Carpenter releases, and you’ll see familiar names appearing alongside the artist—including Max Martin, Jack Antonoff, and Dr. Luke.

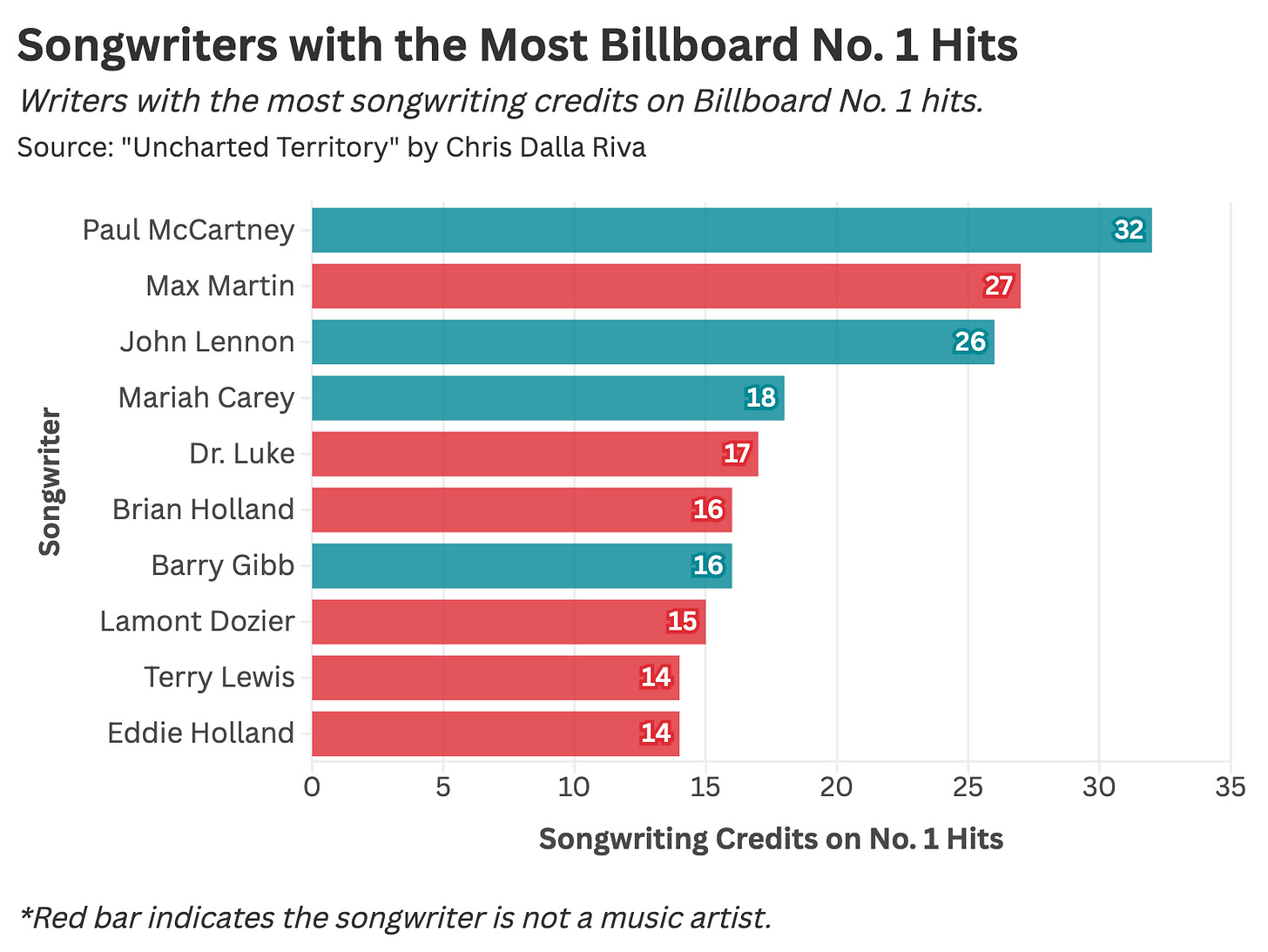

When we look at which songwriters have amassed the most chart-topping credits, the list is dominated not by performers but by professional writers-for-hire, with figures like Max Martin and Dr. Luke only trailing The Beatles and Mariah Carey.

You may notice that all these accomplished non-artist songwriters are men—a detail that pairs awkwardly with pop star gender.

Whenever I have the distinct (dis)pleasure of presenting a dispiriting graphic, I like to invoke a mythic place called Bummer Town. In Bummer Town, every takeaway is a downer, and everyone is upset about it. Twitter loves Bummer Town. So does The New York Times Opinion section.

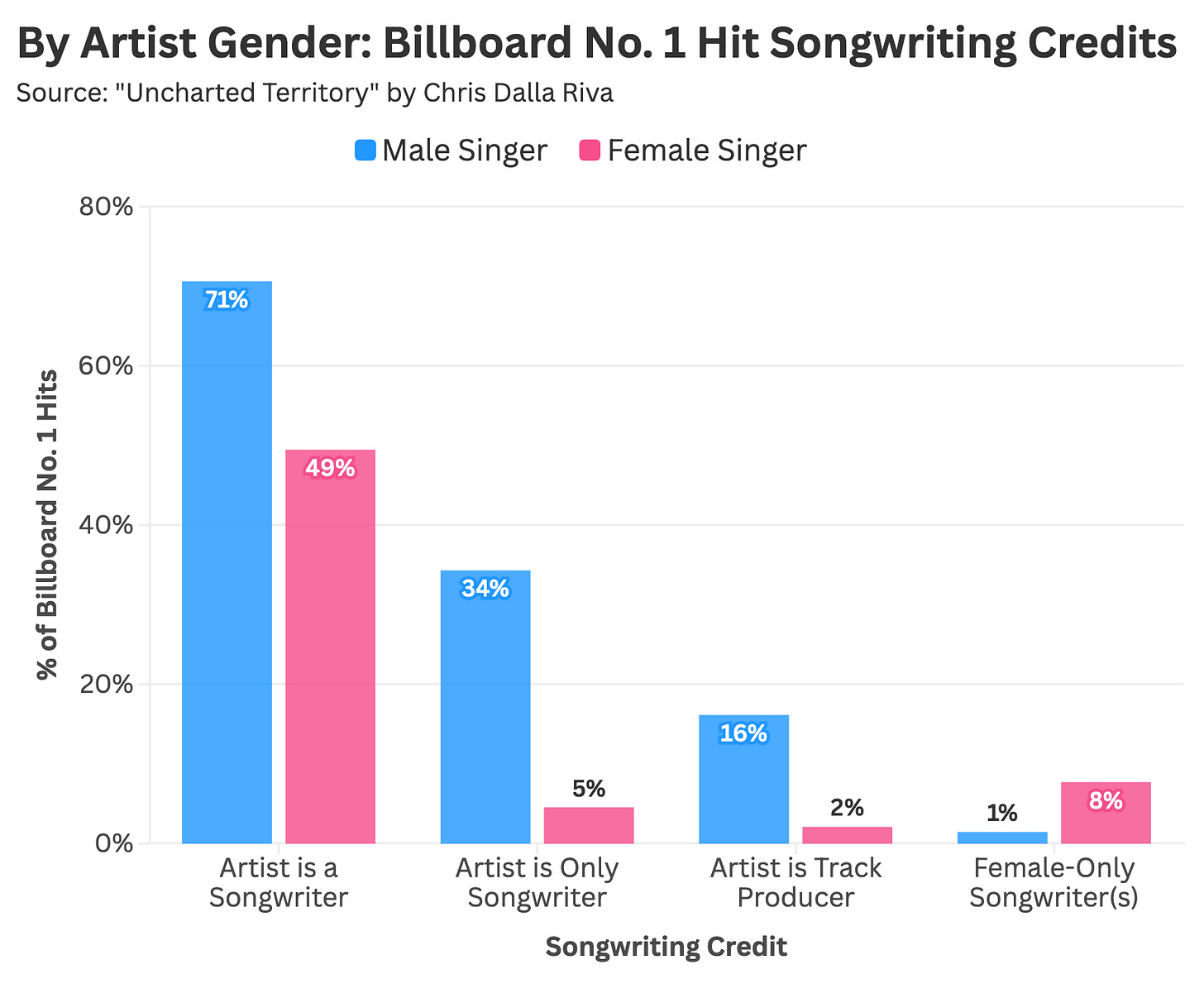

In this week’s visit to Bummer Town, we compare songwriting credits for female and male artists—and find that male artists receive higher rates of songwriting recognition, sole authorship, and producing credits across the board.

You may look at this graphic and think, “perhaps this data is being bogged down by patriarchal social norms from the mid-20th century.” Unfortunately, no—we have yet to exit Bummer Town.

Instances of female-only songwriting credits for chart-topping songs have dipped to zero in recent decades, having peaked in the 1990s—an era that saw the rise of singer-songwriters like The Indigo Girls and Alanis Morissette alongside showcases like Lilith Fair.

This trend is partly rooted in the decline of rock and the classic singer–songwriter tradition—genres that produced Top 40 artists known for distinctive solo songwriting, like Carole King, Joni Mitchell, and Heart.

Yet this shift also goes beyond genre preference, signaling a larger re-systematization of the modern hit factory.

The Brill Building has given way to the Top 40 music guru collaborator: a trusted, deftly skilled (usually male) songwriter-producer who can engineer chart-topping material by pairing an artist’s brand and vocal strengths with a sticky commercial sound. For record labels and artists alike, bringing in Jack Antonoff or Max Martin mitigates risk, ensuring Sabrina Carpenter’s next album performs exactly as expected.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: The End of Rockism

In 2004, Kelefa Sanneh’s New York Times essay “The Rap Against Rockism” challenged the long-standing belief that only “authentic,” self-written, guitar-forward music deserved critical respect. His piece helped usher in poptimism, a counter-framework that celebrates the craft, pleasure, and cultural impact of pop, R&B, and hip-hop with the same seriousness once reserved for The Beatles, Nirvana, and other rock legends. Over the next two decades, as pop stars reshaped mainstream taste and rock’s commercial footprint shrank, poptimism became the dominant critical lens for evaluating music.

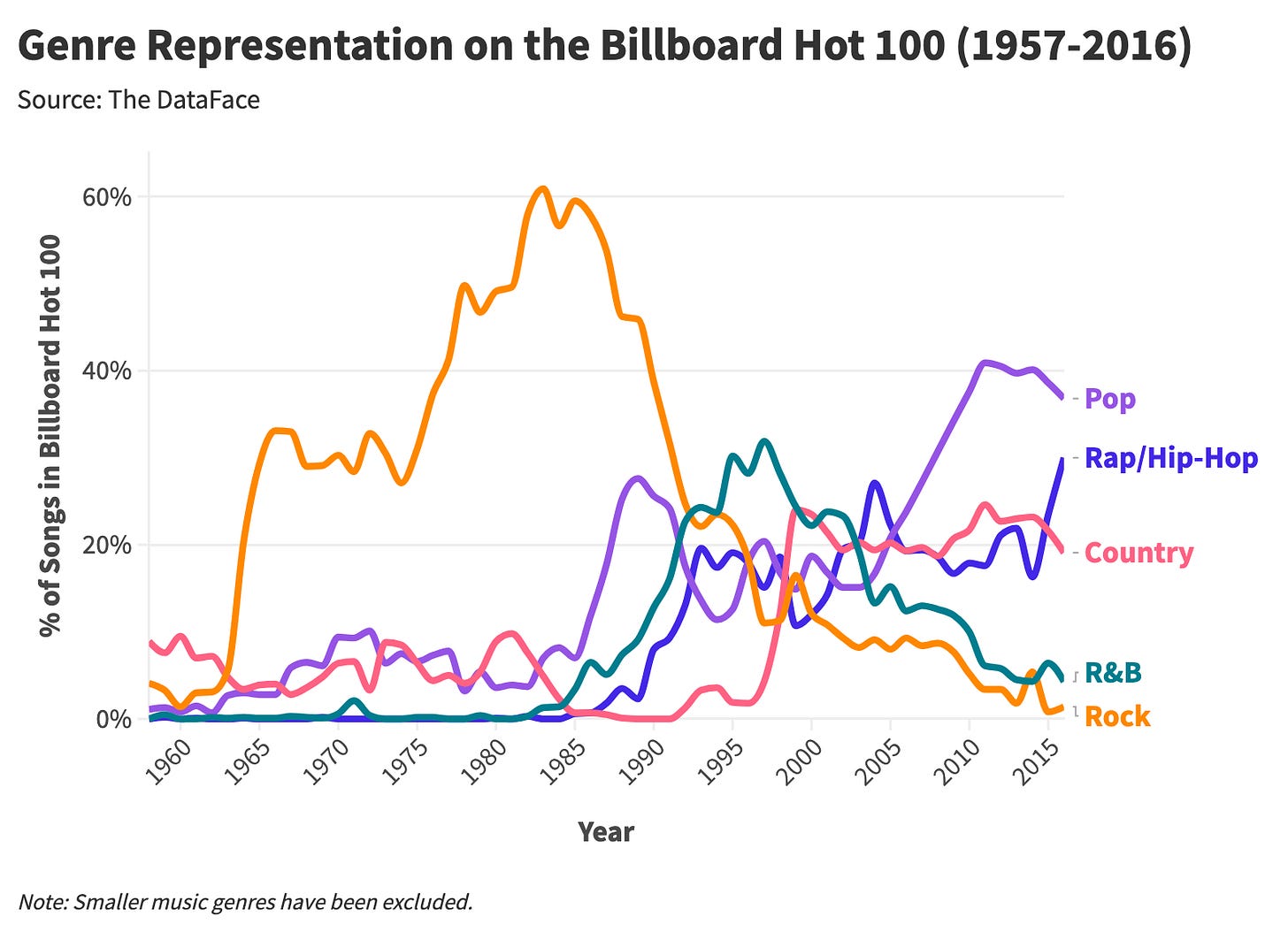

Despite my personal inclination toward rock, I believe this shift was a necessary correction that reflects the cyclical nature of genre popularity. For listeners who came of age in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, rock and the standards it championed were omnipresent. But when you zoom out and examine Billboard Hot 100 genre composition from a bird’s-eye view, rock’s monocultural reign is surprisingly brief—roughly a twenty-year window beginning in the early 1960s and fading by the mid-1980s.

Rock burned bright for two decades, and then it was gone, sequestered out of the mainstream. What’s striking is how neatly this period of dominance overlaps with the rise of mass-distributed music criticism (Rolling Stone, Creem, Spin, etc.) and the cultural coming-of-age of the Baby Boomer generation. Because this era’s chart-topping artists wrote their own songs and played guitar, critics codified solo authorship and instrumental virtuosity as the prevailing criteria for all Top 40.

But step outside this anomalous twenty-year window, and mainstream music history looks entirely different.

Popular music has long flowed through a small cadre of highly skilled songwriters who craft hits behind the scenes—from Cole Porter and Lorenz Hart in the 1920s to the Brill Building staff of the 1960s to modern hitmakers like Max Martin and Jack Antonoff. These writers are preternaturally adept at distilling commercial appetites into songs for others to perform. Against this backdrop, the rockist norms of the 1970s and ‘80s aren’t some long-standing tradition; they were an exception that briefly became the rule.

The music industry’s aesthetics and star personas shift constantly, yet its underlying machinery remains surprisingly consistent—except for a two-decade stretch when rock briefly convinced the world that self-authorship was the only path to success.

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A Recurring Donation:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,700 readers? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd

If you read as many biographies and autobiographies of women artists in the rock era as I do, you come to realize how often women in that era were denied songwriting credits by their labels and producers even when they contributed significantly to a song. This is a longstanding problem in an extremely male-dominated industry where major female artists have always struggled against being told what they are allowed to sing, wear, etc.

So I don't doubt your analysis given the data that exist. The problem is with the dataset itself, which doesn't reflect the reality of who actually wrote the songs.

Excellent summation. As you point out, the rock model (self written, virtuosic) was short lived, and there are other models for commercial success. The American songbook was entirely built on professional writers providing material to expert interpreters. That was also true for Western classical music--other than Chopin, Liszt and a few others, the great classical composers were not the main performers of their work.

You have yourself published articles here pointing out that popular music is getting more uniform, or standardized, and less internally "interesting". My own opinion is that this homogenization is not a good thing. It's not just a matter of taste--brains exposed to less variety of stimuli lose some of their flexibility and even physically lose neural connections. Your thoughts on the intersection of your present article and your earlier work?

Finally, a question: what do you foresee happening with the emergent use of AI to write songs? Given that AI by definition requires training, is originality endangered?

Thanks again for posting this! It is a good complement to my earlier piece on "The songwriters who ate America" https://zapatosjam.substack.com/p/the-songwriters-who-ate-america-part for those who are interested.