Do Actors Get Better With Age? A Statistical Analysis

How does an actor's age influence critical acclaim, commercial success, and casting opportunity?

Intro: How Not-Young Is Robert De Niro?

2019's The Irishman was touted as a breakthrough in cinematic de-aging technology. Martin Scorsese's gangster epic promised to make Robert De Niro (then 76) and Al Pacino (then 79) look decades younger, allowing them to portray characters in their 20s, 40s, and later as dying men in their 80s. The end product was notable (they tried their best) but not particularly convincing.

Watching this movie made me feel like a bad person: For the first two hours, I was singularly preoccupied with how not-young Robert De Niro looked while portraying a 30-year-old gangster. His facial features were de-aged a few decades, but his movements and posture were those of a 70-year-old. At one point, De Niro awkwardly shoots a fellow gangster before making a modestly paced getaway, and I winced, and then I felt bad for wincing, and now I feel bad for writing about it.

Watching The Irishman prompted a low-stakes moral conundrum:

Was I being ageist?: Younger actors frequently play older characters, so why not the reverse? Have I internalized some societal bias against aging performers?

Did this casting decision diminish the film's entertainment value?: Movies rely on the suspension of disbelief, and this scenario may have been a bridge too far. If you're paying attention to De Niro and Pacino's physicality, you're not paying attention to the story, which means this filmmaking choice was a miss. Viewers can assess ethics and entertainment value independently.

The Irishman suggests that older actors may, in certain cases, be better suited for much younger roles. While the success of this experiment was debatable, the attempt challenged long-held assumptions about how age dictates casting and career trajectory. Do actors like De Niro and Pacino actually improve with age, only to be sidelined by entrenched industry norms? And is this question even answerable, given how Hollywood operates?

So today, we'll examine how an actor's age influences critical and commercial success, how casting opportunities evolve over time, and how Hollywood's attitude toward aging has shifted over the past two decades.

Do Actors Get Better With Age?

There is one major caveat to this analysis: the core question is highly complex, maybe even unanswerable. Yet this unanswerability is what makes the topic worth exploring. The crux of the problem lies in causality: if Hollywood systematically avoids casting older performers, then our dataset will reflect industry bias rather than moviegoer preference.

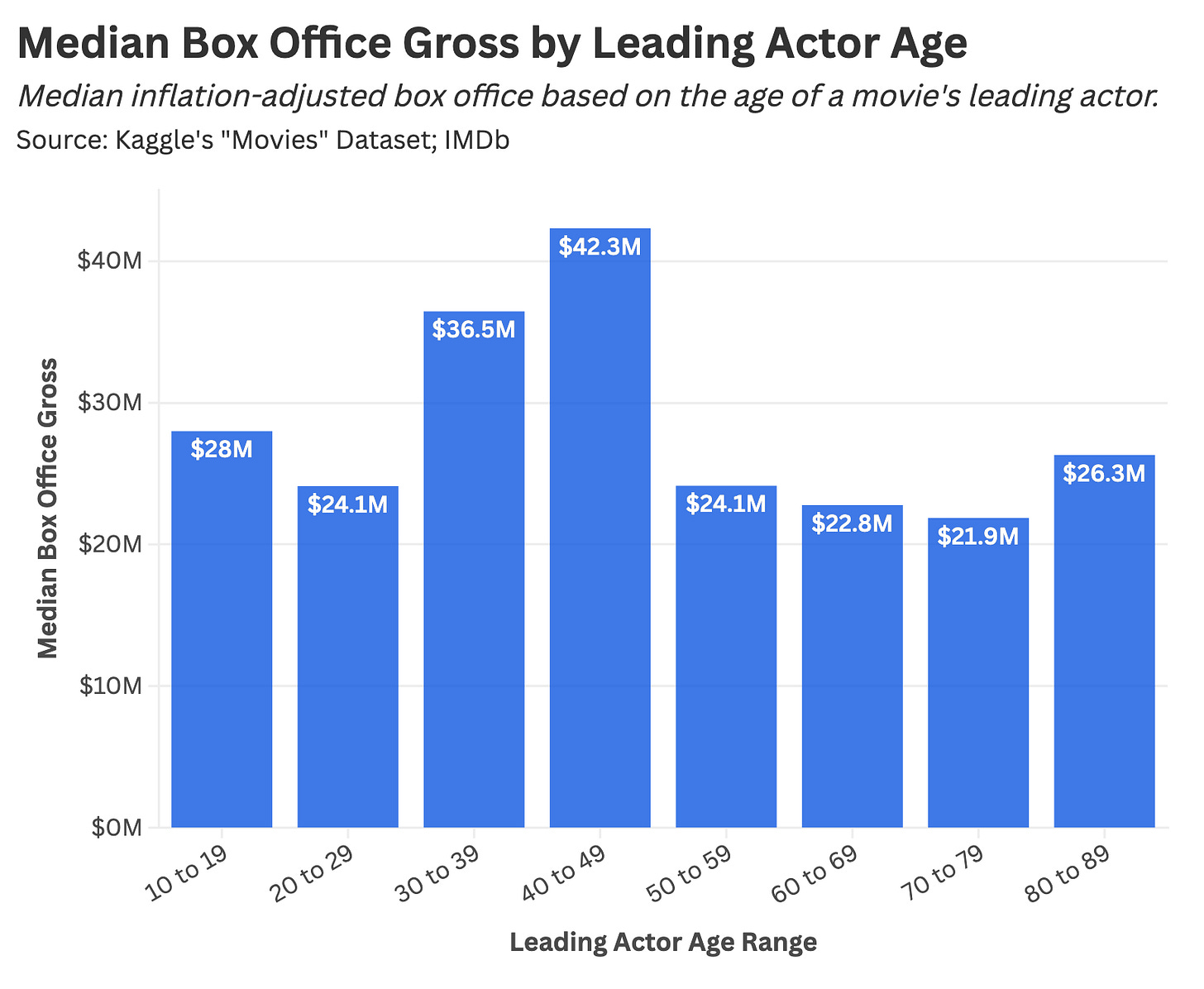

For instance, average box office gross peaks for lead actors in their 30s and 40s before a substantial drop-off following middle age. But is this decline driven by audience demand or by the limited roles offered to aging performers?

To separate these effects, I trained a model to estimate box office returns based on performer age, movie budget, year of release, and online star rating. The raw outputs of this model should not be taken verbatim, since I could spend years working on this stats problem and never ascertain the capital "T" Truth. But if you are curious, the model suggests:

Each additional $1 in film budget yields about $2.70 in box office revenue (inflation-adjusted).

On average, each additional year of lead actor age corresponds to a $600k decline in box office (inflation-adjusted).

I will stress again: these numbers should not be taken at face value (the model is relatively lightweight and its output reflects some degree of industry bias). The main takeaway is an absence of evidence: this dataset cannot prove that actor seniority benefits commercial performance.

Yet commercial bankability is not the sole measure of career success. Vin Diesel is among Hollywood's most reliable box office draws, but few would mistake whatever-he-does-while-onscreen for acting prowess. This brings us to cultural cachet and prestige—currencies Vin Diesel loses with every Fast & Furious installment (with the exception of Fast Five).

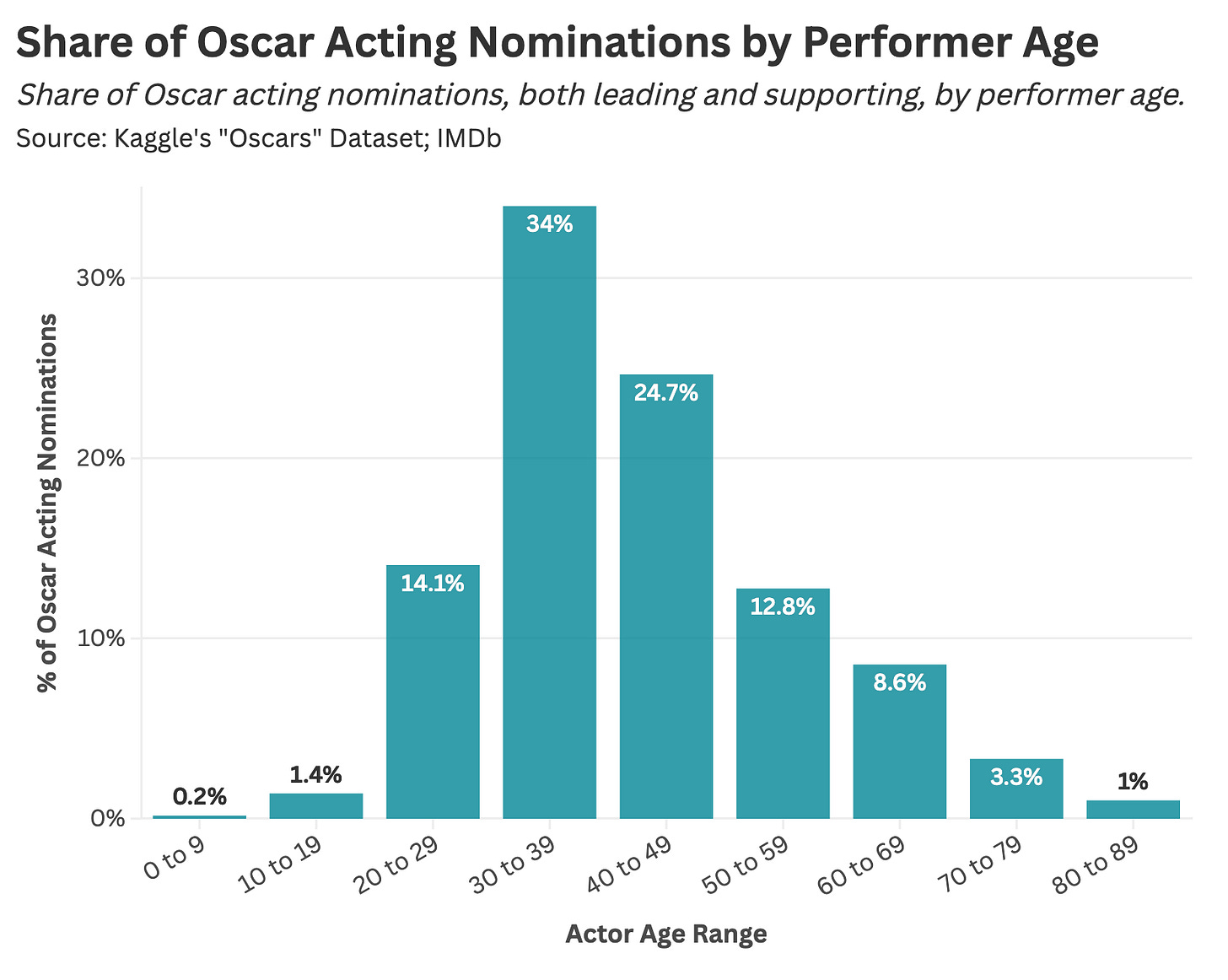

Are older actors, who are often overlooked by big-budget blockbusters, more likely to receive Oscar recognition? In short, no.

I reviewed all Oscar nominations since the award's inception and found two trends:

Oscar nomination odds are similar across age groups: A performance from a 60-year-old has the same likelihood of earning a nomination as that of a 30-year-old.

Raw nomination counts reflect other industry trends: As with box office success, Oscar recognition (by sheer frequency of nomination) is disproportionately concentrated among performers in their 30s and 40s.

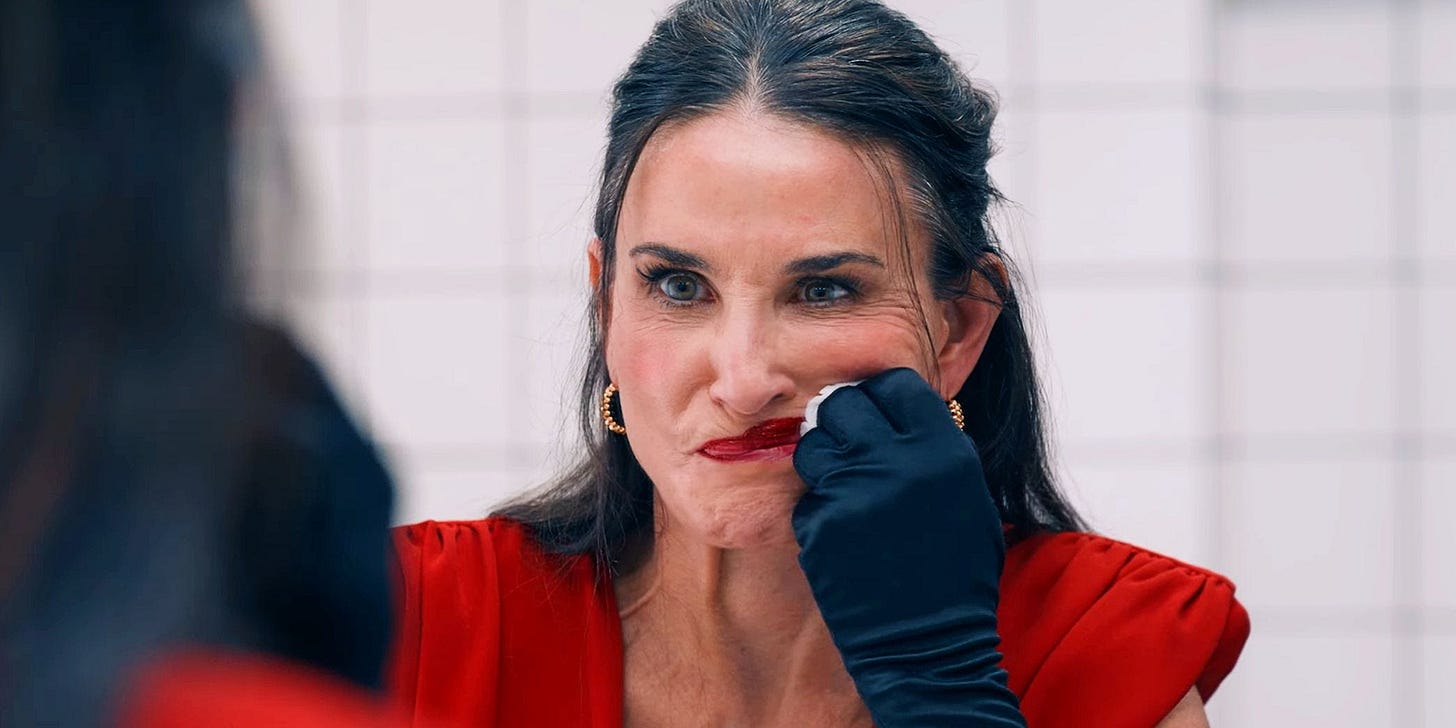

Consider 2024's Best Actress race between Mikey Madison (Anora) and Demi Moore (The Substance). The latter is an aging Hollywood star in a body horror film about the harshness of beauty standards, and the former is an up-and-coming ingénue in a Cinderella tragicomedy.

In The Substance, Demi Moore plays a fading television star who consumes a mysterious liquid that allows her to sprout a younger version of herself (quite disgustingly). This younger Demi-spawn temporarily sustains her relevance in the entertainment industry until the situation spirals out of control (also quite disgustingly).

The Academy saw this movie, applauded Moore for her "bravery," praised the film as a profound takedown of unfair industry norms, and subsequently crowned the 26-year-old Mikey Madison Best Actress. The entire ordeal reads like a metatextual extension of The Substance: Moore's nomination and subsequent loss amplify the film's thesis (and would be considered too on-the-nose had it not actually happened).

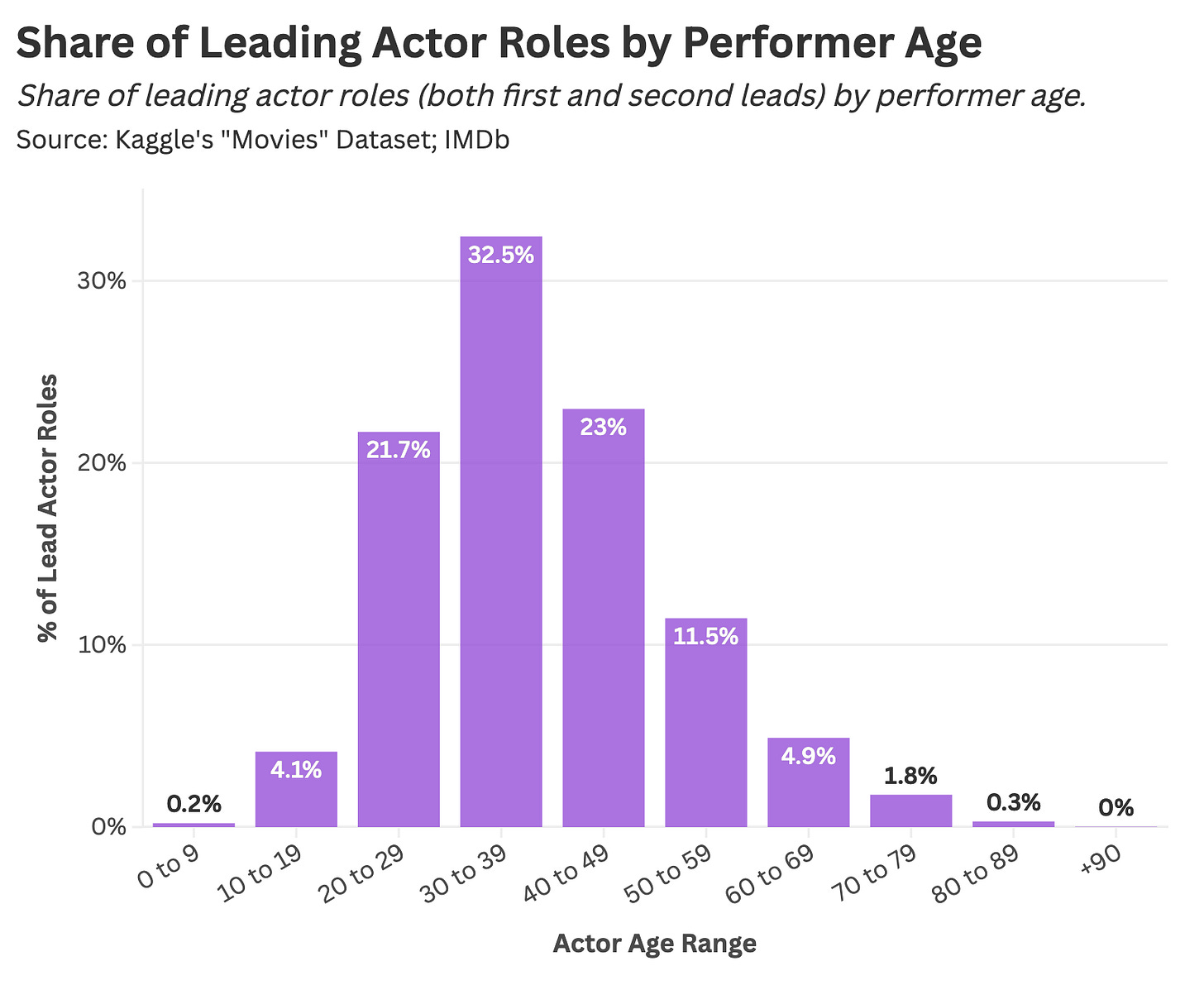

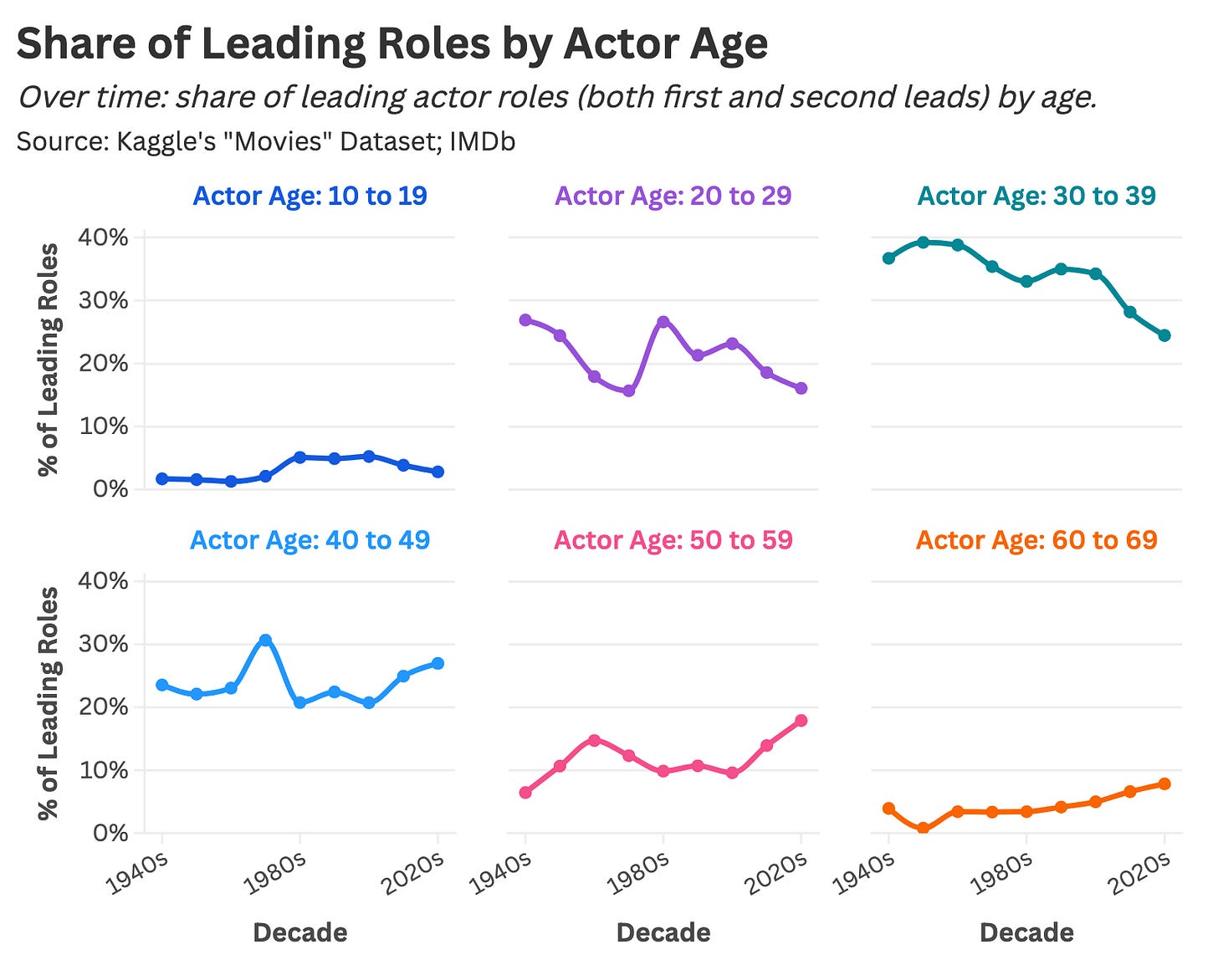

Over the past century, around 75% of lead roles have been given to actors between the ages of 20 and 49, which explains why Oscar nominations tend to cluster in this range.

Yet things are beginning to change. Recent shifts in the entertainment landscape have started to reward older actors, altering the trajectory of the prototypical Hollywood career.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Are Movie Stars Getting Older (On Average)?

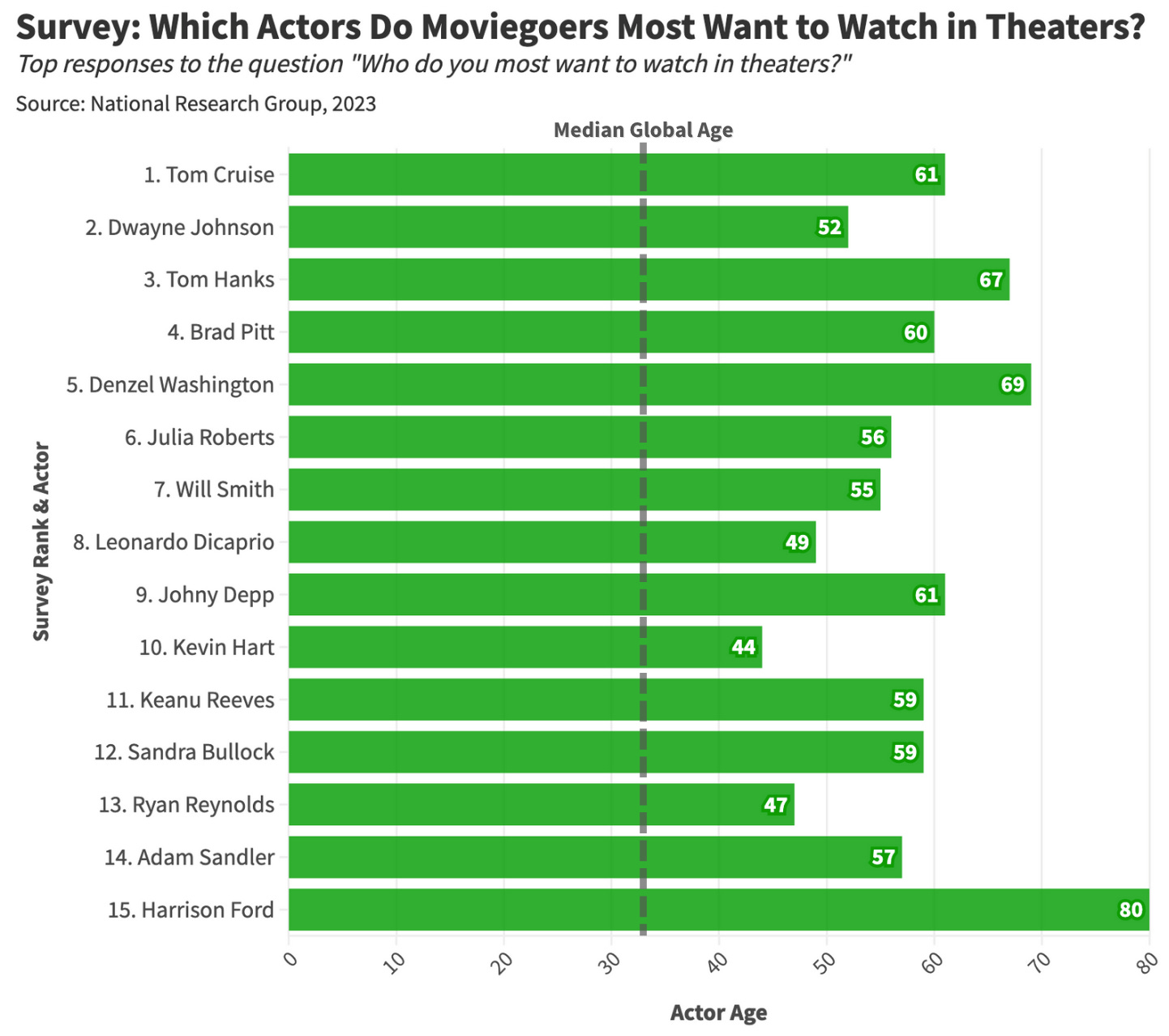

In late 2023, a survey conducted by the National Research Group asked consumers, "Which actor do you most want to see in theaters?" Put simply, the results were weird: not a single actor in the top 15 was under the age of 44. These findings spawned a (minor) existential crisis for industry pundits, fueling two brain-melting months of online discourse.

Arguably, the most surprising aspect of these results was the absence of up-and-coming performers like Zendaya and Timothée Chalamet, actors who have proven box office success (albeit in intellectual property like Wonka and Spider-Man), with Zendaya ranking 49th and Chalamet falling to 94th.

The survey suggests the late 2000s as an inflection point for movie star bankability. Hollywood performers can be divided between the IP-originators and the IP-inheritors, with the originators maintaining a hold on popular imaginations years after they first created iconic characters (like Captain Jack Sparrow or Fighter Pilot Maverick). Johnny Depp's Pirates of the Caribbean and Will Smith's Bad Boys were released before 2010, so their celebrity is assured (regardless of bad behavior), while those attempting to build careers after this point struggle to accumulate cultural capital.

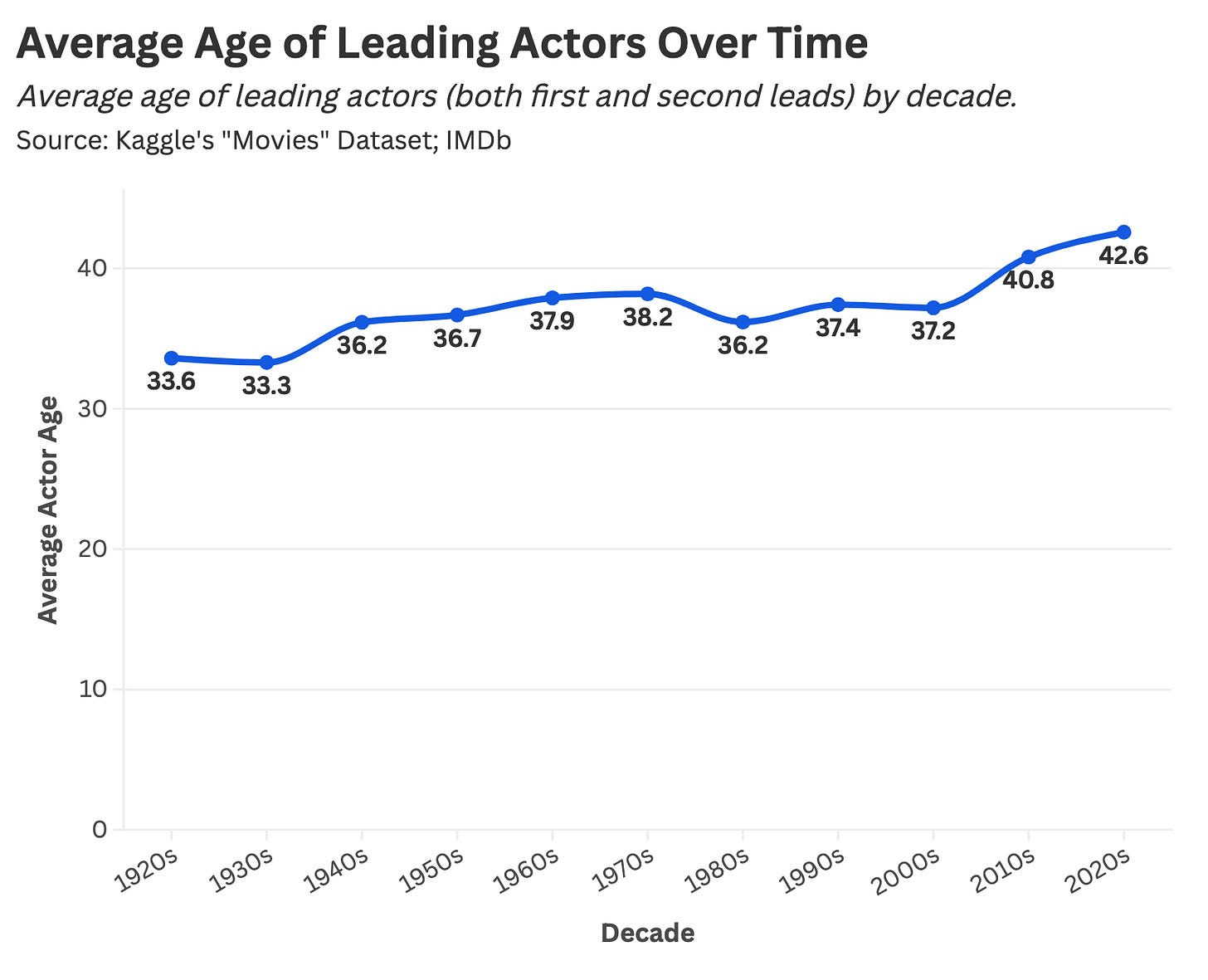

As a result, the average age of leading actors has risen over the last twenty years.

Looking at the breakdown of leading actors by age group reveals a growing share of star performances coming from actors in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, replacing those in their 20s and 30s.

In an industry that struggles to monetize or market anything new, seniority has become a valuable asset.

Final Thoughts: The Immortality of Iron Man

In 2023, Disney did what it does best: monetizing nostalgia with minimal innovation—this time releasing a fifth Indiana Jones movie. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny would have made $400 million worldwide and been promptly memory-holed if not for one fascinating wrinkle: the film brought back an 80-year-old Harrison Ford as its titular hero.

Now, I should be upfront about the fact that I have never seen this movie. I have, however, watched this film over strangers' shoulders on at least thirty different airplane flights. For some reason, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is watched by two to three people in my immediate field of view on every flight (along with The Zone of Interest, quite strangely), and I somehow can't look away, which means I have consumed this film ten times (albeit in Memento-like fragments and without sound).

Watching an 80-year-old Ford play Indiana Jones fosters a sense of cinematic whiplash. This character repeatedly finds himself in peril reminiscent of a Final Destination movie, but he lives every time. Jones' cartoonish invincibility is central to his appeal. You want to see how he'll survive each predicament. In Dial of Destiny, a strange dissonance emerges: while Indiana Jones is entertainingly immortal, Harrison Ford is not.

To clarify, I'm not criticizing Disney's decision to cast Ford in a big-budget film; it's perhaps the most interesting aspect of this movie. What I am criticizing is the logic underpinning the project's conception. Corporate strategy dictates that an Indiana Jones movie be produced every ~11.2 years because money. There is no Indiana Jones without Ford, so this is Disney's last crack at the franchise before they have to mount a soul-crushing reboot with Pedro Pascal (since he is seemingly the lead of every movie produced since 2023). Sadly, Dial of Destiny is not a profound exploration of an unkillable adventurer's mortality; it's a cash grab monetizing Ford's likeness one last time.

The franchise entertainment hype cycle relies on stunt casting to make the old seem new. A reboot is announced, and this news is quickly followed by a series of melodramatic casting decisions, such as "Pedro Pascal is Lara Croft Tomb Raider" or "Pedro Pascal is all the Gremlins." Before such an announcement, I would have derided a Gremlins reboot; now, I want to see if Pascal can pull it off. However, novelty has ceased to be an asset for stunt casting. In August of 2024, Marvel paid Robert Downey Jr. over $100 million to return to the MCU as an entirely different character in two films, a mere five years after killing off Downey's Iron Man. Marvel helped foster a world where pre-2010 IP-creating actors matter most, which means they have no choice but to pay Robert Downey Jr. boatloads of money.

Perhaps Hollywood is now post-age, where the popularity of recognizable superheroes and pirates outweighs industry prejudice against seniority—an odd silver lining to the franchisification of film. Maybe cinematic de-aging technology has struggled to catch on because audiences only want to see Iron Man, regardless of Robert Downey Jr.'s age or the role he plays.

Got a Data Challenge? Stat Significant Can Help!

Struggling to turn your data into actionable insights? Need expert help with a data or research project? Well, Stat Significant can help.

We help businesses with:

🔍 Insights That Improve Performance: Turn raw data into strategic intelligence that guides smarter decisions.

📊 Dashboards That Drive Action: Transform your data into clear, interactive dashboards, giving you real-time insights.

⚙️ Data Architecture That Automates Reporting: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Love this analysis, especially that last paragraph.

In regards to the chart depicting "who do you most want to watch in theatres," most of those actors had their "peak" in the 80s, 90s and 2000s when young Gen X and older Millennials were coming of age. So a lot of it, like you kind of said, has to do with nostalgia-bait. And young Gen X and older Millennials now have the time/money to spend on going to the theatres (which is very expensive, as we all know). And they're now having children and wanting to take them to see the actors they loved growing up. I think most of the age thing has to do with who has the buying power right now and how those people want to see people their age or older in movies. And I think these actors listed feel "safe" to people who are middle aged now and people love to feel safe and watch something with some familiarity, especially in this political and social climate.

I'm also curious if all of the charts are cumulative in regards to gender, because we all know that the older women get, the less likely they are to get cast - again, as evidence in the "who do you most want to watch in theatres," I see Julia Roberts and Sandra Bullock are the only women.

So I'm astonished you didn't break this down by gender. There is so much discussion (and lawsuits) of female actors losing significant screen opportunities (in news media, for example) due to age that it HAS to be relevant. I didn't think you were being ageist, but I was surprised at your lack of curiosity about the potential for sexism to be a meaningful factor.