Can TikTok Revive Classic Songs? A Statistical Analysis of Social Media Virality

Quantifying TikTok's impact on music popularity.

Intro: "It's Probably a TikTok Thing"

Every so often, the media selects a single cultural phenomenon to decode the actions of an entire generation. Consequently, journalistic explorations of teen culture—whether that be for Gen Z or Millennials—are filtered through the prism of a single musician, movie, or technology. Historical examples include:

Teenage Baby Boomers and Beatlemania

Gen X apathy, Nirvana's album Nevermind, and the every action of Kurt Cobain

Millennial adoption of peer-to-peer social networks and the rise of meme culture

Post-COVID, TikTok has emerged as a cultural cipher for interpreting the habits of Gen Z and Gen Alpha, with every baffling trend attributed (quite lazily) to a short-form video app.

For confusing slang: "It's probably a TikTok thing."

For newfangled health trends: "That sounds like a TikTok thing."

For each and every piece of new music: "They're probably big on TikTok or something."

This last point is relevant to our analysis today: mainly, that TikTok has become synonymous with musical taste-making.

Two recent data points further reinforce the app's perceived music industry dominance:

An estimated 85% of videos on TikTok feature music, utilized in everything from dance challenges to cooking videos to "day in the life" recaps.

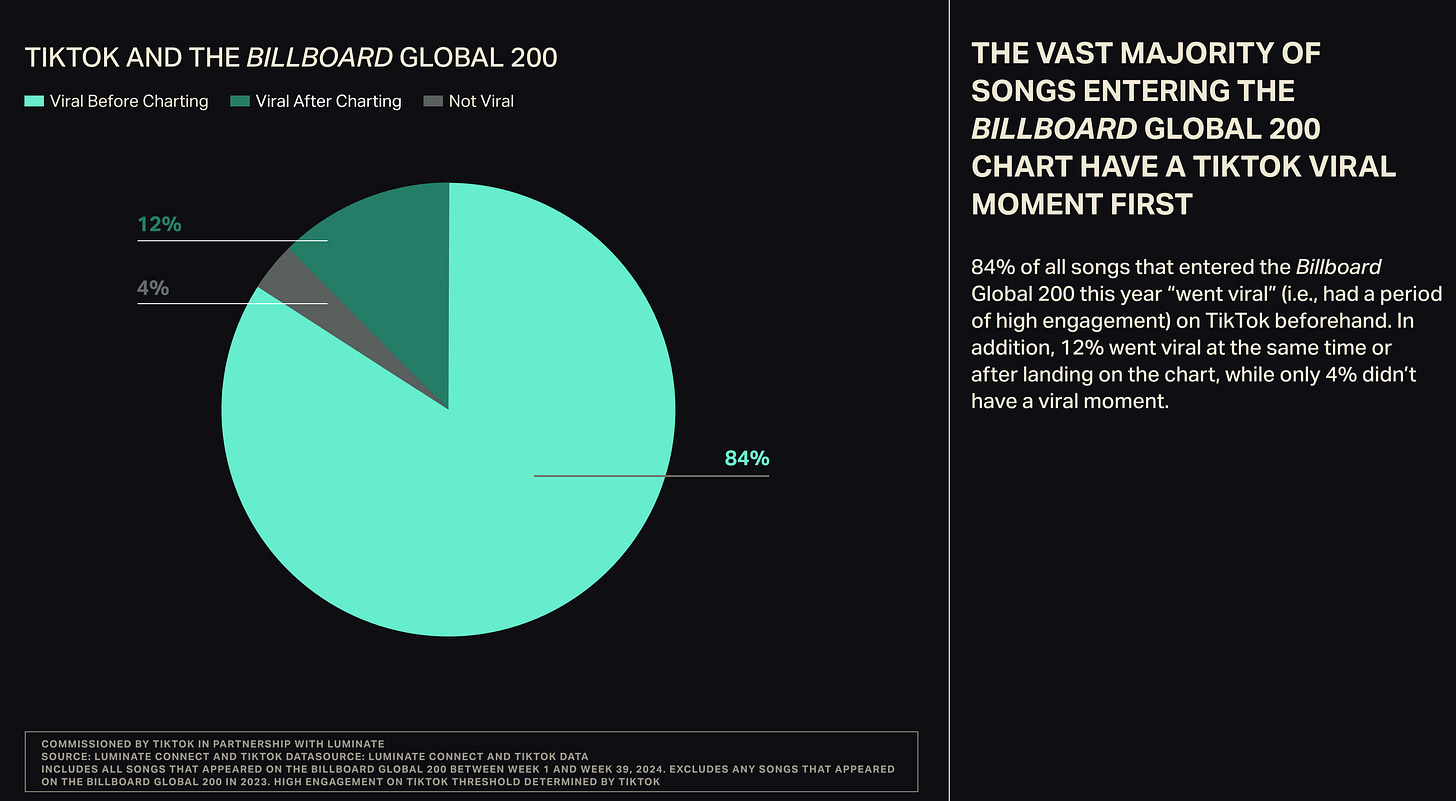

According to TikTok's totally-not-biased research team, 84% of songs on the year-end Billboard Top 200 went viral on the platform before reaching the Top 200 charts, which you can see detailed in this aesthetically unpleasant pie chart:

And yet I remain skeptical: if TikTok were music's ultimate tastemaker, it would have the power to bestow virality upon overlooked classics and emerging artists alike, rather than just amplifying the momentum of up-and-coming songs. This raises an intriguing thought experiment: which long-dormant artists have been embraced by TikTok, and do these musicians benefit from repeat use on social media?

So today, we'll examine the retired musicians heavily featured on TikTok, determine whether their digital resurgence translates into lasting fandom, and evaluate how short-form video has reshaped our relationship with music—for better or worse.

Can TikTok Revive Classic Songs?

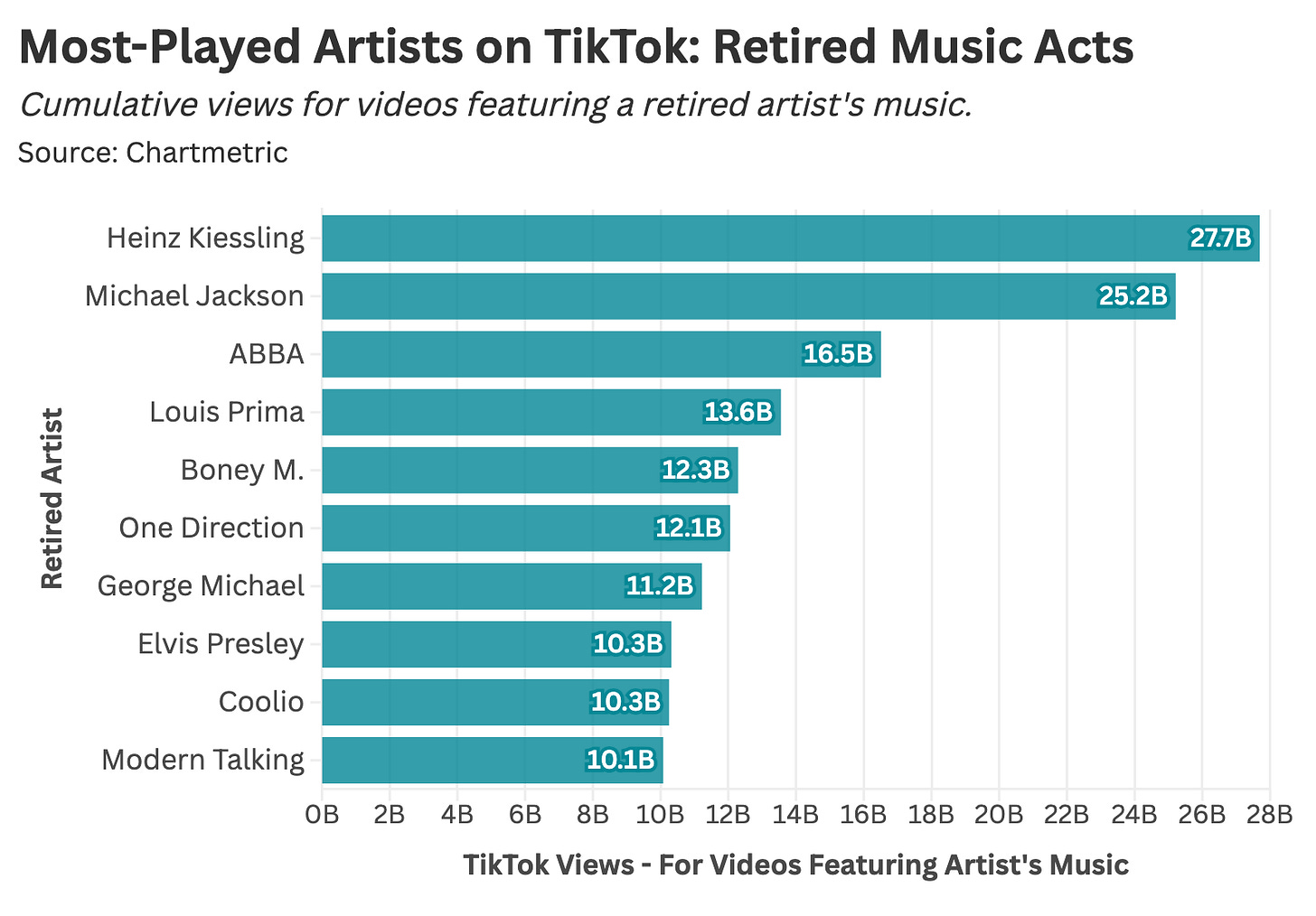

Heinz Kiessling was a German composer best known for crafting whimsical scores for film and television. If you've never heard of Kiessling, you may be astonished to learn that the work of this unknown composer has garnered 27.7 billion views on TikTok, making him one of the platform's most heavily featured artists.

In fact, our list of retired musicians frequently sampled on TikTok is a bizarre hodgepodge of all-time greats—ABBA, Michael Jackson, and Elvis—and acts obscure to contemporary audiences—such as Louis Prima, the aforementioned Heinz Kiessling, and Modern Talking.

To better understand TikTok's fascination with these long-dormant musicians, we'll highlight each artist's most popular track on the platform. Many of these selections are lesser-known entries from celebrated discographies, frequently repurposed for distinct social media trends.

The common thread among these songs is the ease with which they can be distilled into 20 seconds of meme-ery. Consider ABBA's "Happy New Year," which is a relatively obscure title in the band's much-revisited discography. This tune is so irrelevant to ABBA's legacy that it did not make the cut for Mamma Mia or its sequel Mamma Mia: Here We Go Again. Despite appearing in over 2.3 million TikTok videos, this track currently ranks as ABBA's 26th most popular song on Spotify, receiving 4% of the streaming activity generated by "Dancing Queen."

Few TikTok users encountered "Happy New Year," absorbed the track's artistry, and then sought it out on Spotify—its social media prominence has done little for its cultural legacy.

The same holds for artists like Heinz Kiessling and One Direction (which is the first time these musicians have been mentioned in the same sentence). Frequent TikTok usage of Kiessling's It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia theme or One Direction's "Still the One" does not translate into broader streaming success on Spotify.

This phenomenon extends to the platform's most-played tracks of all time. Analyzing the songs with the highest cumulative views on TikTok reveals an unmistakable contradiction: collectively, these tracks have amassed nearly 800 billion views, yet you've likely never heard of them.

My experience sorting through these songs followed a predictable pattern: I was initially puzzled by anonymous titles like "Monkeys Spinning Monkeys" or "Funny Song," only to realize that I'd heard these tracks as nondescript background music in countless social media videos.

These works are widely heard but rarely internalized. Consequently, their ubiquity on TikTok has no meaningful impact on Spotify listenership, which we can see by benchmarking their cumulative streaming volumes against PSY's "Gangnam Style" and Ylvis' "What Does the Fox Say?" (society's great cultural yardsticks).

Ultimately, the relationship between TikTok and music follows one of two models:

TikTok Provides a Moderate "Nudge" to Already-Ascendent Tracks: The app primarily boosts newly released songs that already have industry backing or existing momentum. The platform cannot revive tracks (like "Happy New Year" or "Che La Luna") that have faded from the zeitgeist or were obscure upon release.

TikTok Utilizes Music in Two Distinct Ways: Songs featured on TikTok broadly fall into two different categories. In one, the music itself takes precedence, actively foregrounded for listeners to internalize and later stream. In the second, tracks serve as background music, functioning like "audio memes" that maximize video virality rather than deepen engagement with that song.

Both scenarios reveal a curious paradox surrounding TikTok mainstays like Heinz Kiessling and Louis Prima: can musicians without name recognition be considered obscure when their music has accumulated ~28 billion listens?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

Final Thoughts: A New Generation of Muzak

Analyses of youth culture typically share one critical flaw: they're rarely conducted by young people. As a result, contemporary teenage behaviors are frequently interpreted through the lens of middle-aged culture critics, who seem to forget that they once rebelled against similar criticism. This has produced countless think pieces framing the music, movies, and communication technologies favored by teens as morally hazardous and inherently inferior.

It is with this in mind that I—a morally superior 32-year-old—downloaded TikTok to better understand said youth. During this trial period, I absorbed all the app had to offer: dance challenges, aspiring comedians, cooking videos, political propaganda that affirmed my beliefs, "day in the life" content, silly cats, political propaganda that conflicted with my beliefs, silly dogs, and all other thoughts broadcasted by humanity at that moment in time.

After a week, I deleted TikTok and have yet to re-download the app. Now I know what you're thinking, "how brave of this guy, fighting back against social media!" And to those people, I say, "Not really." I didn't delete TikTok out of some lofty sense of superior taste but because I found the platform to be too entertaining.

Imagine if the awe you felt upon first seeing dinosaurs in Jurassic Park were distilled into an endless stream of 20-second clips, delivered by an algorithm perfectly attuned to your desires. Using this app, hours melted away like nothing, and yet I retained less than 5% of what I watched—the content was subordinate to the sensation of being served such wonderful content.

In this sense, TikTok's use of music—both mainstream and obscure—functions much like muzak (spelled with a "z" and "k"! 😱). The term "Muzak" was coined in 1934 by George Squier, who combined "music" and "Kodak" to brand his company's service of supplying anonymous background songs for businesses, elevators, and other public spaces. The premise behind muzak was simple: sometimes people prefer a middle ground between silence and active listening. TikTok thrives in a similar intermediate space, where music enhances experiences without demanding conscious attention or explicit appreciation of its artistry.

Equal parts affecting and inconspicuous, this emergent category of muzak now soundtracks our digital lives, headlined by works like "Monkeys Spinning Monkeys," "Happy New Year," "Funny Song," "Che La Luna," and the compositions of Heinz Kiessling. And if you've somehow reached this sentence and have no idea what I'm talking about, you can rest easy knowing "it's just a TikTok thing."

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at daniel@statsignificant.com, connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

While there are exceptions (Noah Kahan comes to mind) you're right, and it does hit on my top issue with short form video content -- I don't remember any of it. I avoid short-form video content, not because it provides nothing of value, but because it provides nothing at all.

BUT the proliferation of short-form content has actually introduced me to new music via my Instagram feed. Because everyone I follow has been pressured into making short-form content to stay relevant, I get exposed to music I otherwise wouldn't I certainly have added a fair bit of the indie-folk bands that local farms just love posting baby animals to to the Spotify rotation. But the difference is the curation -- my actual feed are people I actually choose to engage with and actively consume the content, as opposed to the passivity of the "reels" page.

The clear conclusion to draw here is that It's Always Sunny is the cultural tastemaker, not TikTok