Can One Episode Ruin A TV Show? A Statistical Analysis

Can an entire TV series collapse in one episode?

Intro: The Collapse of Game of Thrones

TV shows are an escape from the tribulations of daily life, which makes them all the more painful when they go wrong. Game of Thrones, once America's most popular show, is an unfortunate reminder of how trusting television can induce anguish. After seven seasons, 67 episodes, 4,020 minutes, and countless plot twists, the series' quality began to degrade rapidly.

Game of Thrones' final season sullied the show's sterling legacy, and fans, myself included, were quite pissed. 1.8M Thrones devotees even went so far as to sign a petition demanding HBO "Remake Game of Thrones Season 8 with competent writers." To add insult to injury, the show's final season gave us numerous production gaffes, including rogue coffee cups and water bottles that had no place in the show's fantastical world.

What's most shocking about Game of Thrones' collapse is the speed of the show's decline. Like dominos, one aggressively bad episode cascaded into a season of series-ruining content, eventually rendering the first 4,020 minutes of Thrones to be a gigantic waste of time.

While spectacularly memorable for its downfall, Game of Thrones is just one of many shows to massively disappoint its fans. In fact, there are more disappointing television series than ever—because there are more television series than ever (pretty crazy, right?). From 2012 to 2022, networks overwhelmed their streaming services with a never-ending parade of content in hopes of capturing a monthly payment of $9.99.

We watch more TV than ever and thus run a greater risk of a beloved series betraying our time and trust, sometimes in spectacular fashion. So today, we'll examine the nature of drastic show collapses. How prevalent are these swift declines? And what actions immediately induce viewer frustration?

How Often Does One Bad Episode Ruin an Entire Series?

Can a show collapse in just one episode, or do quality declines manifest slowly? To identify series-ruining installments, we'll utilize IMDB user reviews and the following five criteria:

A series-ruining episode cannot be in season one: there needs to be an established show worthy of viewer frustration.

A series-ruining episode cannot be the last installment of the final season: show quality needs to worsen in the episode's aftermath.

A series-ruining episode's rating should be +15% lower than the average of all previous episodes: this series-ruining installment must represent a stark shift in quality.

The five installments following our series-ruining episode should demonstrate a +15% drop in average rating compared to the five episodes prior: this rapid quality decline should persist immediately following our series-ruining episode.

All installments following the series-ruining episode should demonstrate a +15% drop in average rating compared to all previous episodes: this quality decline should remain for the rest of the show’s run.

Ultimately, about ~2% of television series meet our five criteria. The prevalence of these spontaneously sputtering series is relatively consistent over time, with a notable rise in the 2020s.

This increase could be the product of random chance or, more likely, the result of breakneck television production outpacing content quality. In hopes of capturing market share in the ever-competitive streaming wars, studios are greenlighting works of questionable quality and extending series whose narrative potential has fizzled. TV's golden age comes at a price—and that price is season six of House of Cards and other low-quality content.

When we look at our set of series-ruining installments, we find a high concentration of disaster episodes in the 2010s and 2020s, the latter being particularly remarkable because it's only 2023.

This list showcases some of my greatest heartbreaks: How I Met Your Mother, Game of Thrones, and Scrubs. I vividly remember watching each of these shows and thinking, "Why is this happening? How could adults do this?" Each series' demise felt like a singular devastation, a perplexing enigma, yet there are commonalities in these collapses.

TV shows often face challenges at predictable points, particularly during a season's beginning or end, and (unsurprisingly) during a series' final season. Sometimes, a show's conclusion is decided before production begins, and the resulting execution frustrates its fanbase (Game of Thrones, Roseanne, How I Met Your Mother). In other cases, a series' quality degrades, and the show is promptly canceled without a proper finale (Master of None, Scrubs, Scream).

One genuinely terrible episode can, indeed, destroy a series, whether it's a repudiation of that show's legacy or a catalyst for its termination. But what makes fans lose interest in a show so quickly? What narrative disruptions cause instant viewer frustration, and are there patterns to these artistic choices?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

What Causes A Series-Ruining Episode to Be So Bad?

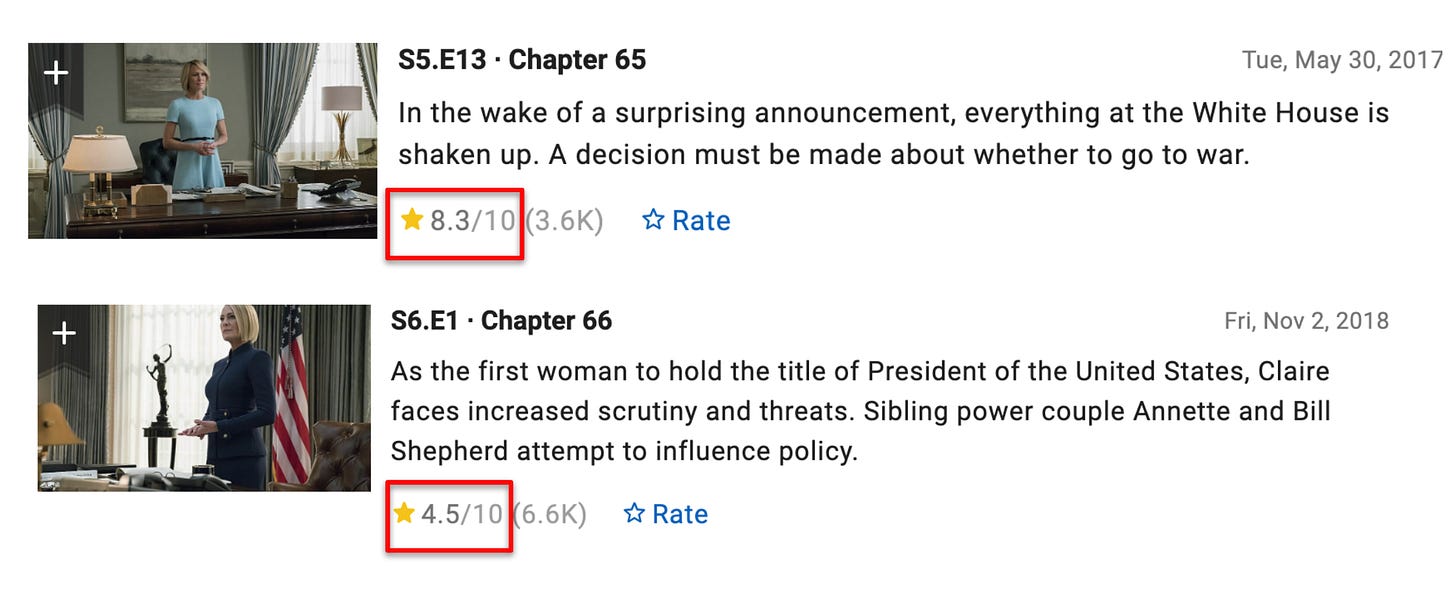

House of Cards' final season was laughably terrible, especially its first ten minutes. As Netflix began shooting the series' last season, several individuals accused Kevin Spacey, the show's lead actor, of sexual assault. In response to the allegations, House of Cards swiftly severed ties with Spacey. And then Netflix did something curious—they went forward with the show's final chapter without Spacey.

With the actor's sudden exit, House of Cards had to address the absence of its central character a few minutes into episode one. In an exposition dump for the ages, one of the characters clumsily announces Spacey's character's death (almost as if reading their lines off a cue card). Then, the plot moves on, giving way to new storylines that were rushed and inadequately developed. By minute eleven, House of Cards had become an entirely new show, absent its greatest asset.

Viewers hated this abrupt shift, and season six's premiere saw a ~46% decline in average viewer rating.

Series-ruining episodes often feature a significant narrative disruption. A central character departs or the show moves toward a highly unsatisfying conclusion, and the magnitude of these misfires subvert the show's appeal. But sometimes, a show's demise is less concrete. These descents don't stem from one failed story element but rather a sweeping decline in writing quality—a collapse less substantial than Spacey's dramatic exit or How I Met Your Mother's killing of the titular mother.

When examining the artistic choices that doom series-ruining episodes, we find that ~40% of installments suffer an indistinct decline in story caliber (the writing just got bad quickly). The other ~60% of our disaster installments stem from unmistakable narrative shifts, such as character exits or poor series resolutions.

At the same time, artistic intent is only one part of the equation. Show implosions, while infrequent, are a statistical inevitability. Much of this has to do with television's episodic nature. The majority of television shows run until they are no longer commercially viable. Indeed, most longer-running shows see a noticeable dip in quality by their sixth season, which intensifies with every subsequent chapter.

Unsurprisingly, over 50% of our series-ruining episodes occur in a sixth season or later, even though long-running shows constitute a mere 6.5% of all content. For showrunners, maintaining content quality for six, eight, or twelve seasons is challenging. But for studios, producing a sixth season of Billions or a third season of Master of None (both absent their former leading characters) is less risky than the first season of a new show. As such, the past twenty years have seen a rise in series running six seasons or more.

There was more TV and, thus, more long-running shows with the potential for legacy-destroying episodes. And yet, production of longer-running series has dropped in recent years, the product of a pandemic slowdown, writer's strike, and an increased focus on profitability for streamers. Perhaps there will be fewer disaster episodes in our immediate future.

Final Thoughts: The Power of Closure

Succession's final season was a rousing success, cementing the series' legacy as one of the greatest television dramas of all time. Critics were effusive in their praise, calling the show's conclusion "a masterclass in television" and "one of the best seasons of television ever made."

What's so remarkable about Succession's finale is the rarity of an ascendent conclusion. TV shows typically run until narrative tension fizzles and viewership declines. Meanwhile, shows ending on their own terms often struggle to conclude years' worth of storylines and satisfy viewer expectations. Succession “landed the plane,” but its triumphant exit is an exceptional case.

The economics of television present a fundamental tension between commercialism and narrative integrity. Unlike movies, TV series craft their stories for longevity, often bypassing plotlines of greater drama and heightened stakes. Game of Thrones' Jon Snow dies at the end of season five, only to be resurrected by magic in the next episode. Homeland's Brody survives an aborted terrorist attack at the end of the show's first season, sacrificing a fulfilling ending to his character arc in favor of his return the following season. How I Met Your Mother teased viewers about the titular mother's identity for over nine years.

Series often sacrifice their stories to preserve their existence. Films, on the other hand, are written with a clear-cut ending. My love of Goodfellas, Good Will Hunting, or Shawshank Redemption will be consistent over time, while my appraisal of an entire television series can change in one episode. 1.8M fans have never petitioned to re-write a new version of Parasite or The Godfather. If viewers dislike a movie, they lament their use of that two hours and then go on with their lives. If viewers dislike House of Cards' final season, they might have regrets about the ~60 hours they spent watching the show.

Television is very good at entertaining us over a long period of time. Yet, trusting a show across multiple years is not without risk.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

How is True Detective, season 1, episode 8 not discussed in this post????

While they aren't as obvious to viewers as actor departures, I'd put forward writer departures as an equally significant factor. Many of the jump-the-shark points you found closely line up with them.

The Boondocks: Creator Aaron McGruder wrote or co-wrote every episode of the first three seasons. The fourth was produced entirely without his involvement.

Doctor Who: Having watched every modern episode, I place the blame for seasons 11 to 13 not on the cast turnover (which is continual on this series) but on the showrunner. Chris Chibnall was a far weaker writer than either of his predecessors, and has writing credits on three-quarters of the episodes he oversaw. All of the other writers in his seasons were new to the series.

Falcon Crest: Season 9 has no writers in common with seasons 1 to 8.

Master of None: Co-creator Alan Yang co-wrote three-quarters of the first two seasons' teleplays, and none of the third season's.

The Promised Neverland: Season 2 episode 4 is the last one by Toshiya Ono, who had written most of the series to that point. Most subsequent episodes are credited to a new writer, the mononymous Nanao. (Although the final two episodes are apparently so shameful that they carry no writing credits whatsoever!)

The Rising of the Shield Hero: Season 1 writing credits are divided between five people. One of those five wrote all 13 episodes of season 2 by himself.

RWBY: Series creator Monty Oum co-wrote almost every episode of the first three seasons, but died before work began on season 4.

Scream: Season 3 has no returning writers from seasons 1 or 2.

Scrubs: Wikipedia says of season 9, "every writer from previous seasons departed from the show with the exception of [Bill] Lawrence and Andy Schwartz. Sean Russell returned to write a freelance episode, just as he had done previously in season 6."

The Terror: Season 2 was created by a completely different set of people than season 1.