Are More Celebrities Dying? A Statistical Analysis

Are more famous figures dying, and if so, why?

Intro: 2016 Was a Bad Year for Celebrities

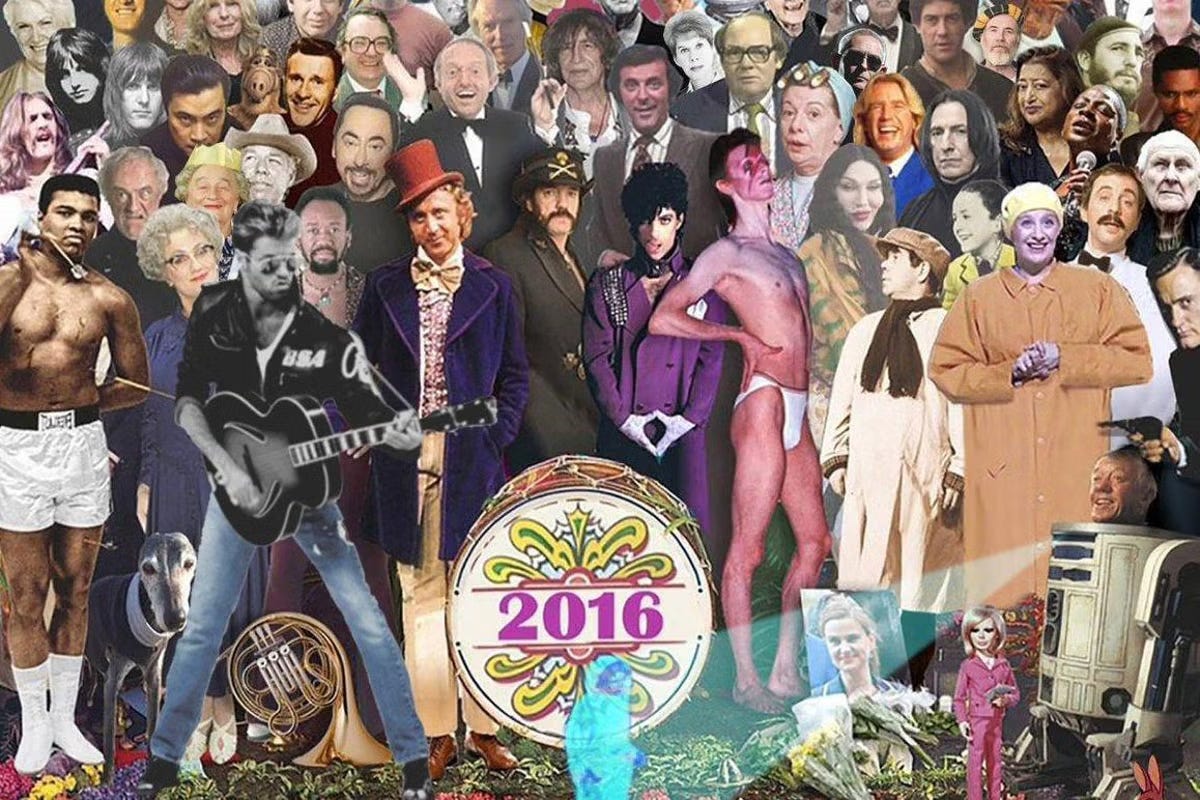

2016 saw the passing of an unusually high number of widely-known cultural figures, including David Bowie, Prince, Muhammad Ali, Carrie Fisher, Gene Wilder, and George Michael. As news spread of each subsequent death (amid the chaotic energy of the presidential election), many social media commentators anointed 2016 "the worst year ever"—though I imagine they would later change their answer to 2020.

News outlets ran stories attempting to explain the occurrence, with some performing (questionable) actuarial analyses to determine if 2016's spike in celebrity deaths was a statistical outlier. Here is a fun little sample of this media coverage:

Have more famous people died in 2016? (BBC)

2016 Was a Bad Year for Celebrity Deaths, by These Measures (NY Times)

No, 2016 wasn't the worst year for celebrity deaths (CNN)

Memes began circulating about which beloved figure would be "next," with internetgoers growing increasingly concerned for the welfare of comedic actress Betty White. One fan even went so far as to start a GoFundMe to "Help protect Betty White from 2016" with the goal of raising $2,000. The fundraiser ultimately collected $9,245—though I have no idea where this money went.

News of recently departed figures has become a staple of our everyday experience as media platforms inundate us with push notifications, obituaries, and long-form profiles of these passings. Anyone consuming this tragedy-forward content may inevitably wonder whether more celebrities are dying or if other factors are driving this perception. So today, we'll explore the media's preoccupation with celebrity passings, the changing nature of celebrity, and the population dynamics that inform this phenomenon.

Are More Famous People Dying?

In the internet age, "New York Times push notification famous" has emerged as a benchmark of notoriety—and a long sought-after goal for narcissists. To be "NYT push notification famous" is to be so noteworthy that your death warrants a breaking news alert from the New York Times. Such an honor means your passing will cause everyone to stop what they're doing, look at their phone, and acknowledge your death. What an achievement.

When someone clicks on this push notification, they'll find a brief obituary that follows a well-worn formula. The title of these articles is something along the lines of "This person, who accomplished an important thing, is dead at 89." The corresponding story usually features a few paragraphs explaining this person's significance and the circumstances surrounding their passing.

Using MediaCloud, an open-source media analysis platform, we can see how often phrases specific to this story archetype occur across all published news. When we search for terms like "dead at," "has died," and "dies at," we see that major news outlets (like NY Times, Fox News, Washington Post, NPR, and so on) are using these phrases more frequently in their content.

Sure, major news publications are dedicating greater digital real estate to obituaries, but does that mean more celebrities are dying? And what does it mean to be a celebrity?

To cross-validate this phenomenon, I referenced the not-so-concisely-named "A cross-verified database of notable people, 3500BC-2018AD," a dataset of every "notable" individual in human history. Curated by a global team of six economists, this database covers millions of historical figures, using factors like Wikipedia page views, number of Wikipedia editions, and Wikipedia word counts to quantify renown.

Using this repository, we see a dramatic rise in deaths from our "notable" population from the 1700s onward, with an acceleration of this trend in the latter half of the 20th century.

Indeed, data from our database of notable figures indicates that famous people are dying at a greater rate. If we accept that more notable figures are passing away, it naturally prompts us to ask, "What makes someone notable?" and "Why are more well-known individuals dying?"

What's Driving The Increase in Celebrity Deaths?

What does it mean to be well-known? What elevates someone to the level of "New York Times push notification famous?" Fortunately, "A cross-verified database of notable people, 3500BC-2018AD" provides ample data to answer these questions, including information regarding each figure's profession.

Looking at this occupation data, we see how the rise of film and television significantly transformed what it meant to be widely known. The latter half of the 20th century saw an explosion of sports stardom and creative celebrity, paired with a decline in well-known painters, lawyers, and journalists. To be on a screen was to be famous.

The professionalization of sports and arts increased opportunities for fame while giving media producers more subjects to document (and later eulogize).

Unsurprisingly, the advent of mass media spurred an abrupt increase in well-known individuals. Our dataset shows an explosion of notable figures in the 19th century, with celebrity births vastly outpacing deaths from this population.

Said differently, with each passing year there are more famous people. But are there more famous people because a greater portion of the population is well-known, or because there are more people (in the world)?

When we look at notable figures as a percentage of global population, we see this proportion grow in the 17th and 18th centuries, followed by a steep decline in the latter half of the 20th century.

If the number of living celebrities is increasing, but their prevalence is decreasing, then the global population must be growing faster than our group of renowned figures. Indeed, when we look at worldwide population over the last 300 years, we see a massive uptick in births following WWII (one could even call this a "baby boom").

So, to recap our findings thus far:

More celebrities are dying than in previous years.

With each year, there are also more living celebrities.

The introduction of mass media fostered an increase in widely-known individuals renowned for their athletic and artistic achievements.

There are also more humans on planet Earth, which likely contributes to the growing count of well-known individuals.

But it's not just the quantity of humans that explains our dismay when a beloved icon dies; it's also the significance we attach to these mortals.

The term "parasocial relationship" was introduced in the 1950s by sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl to describe the one-sided relationships that audiences form with media figures, such as actors, musicians, and athletes. Unlike typical friendships, parasocial relationships are unreciprocated; an individual feels a sense of intimacy with Nicolas Cage or Olivia Rodrigo, even though these figures are unaware of their existence.

There is a sizable market for details on our beloved parasocial friends, as media companies fervently track Taylor Swift's dating life, Lebron's latest feats of athletic brilliance, or Elon Musk's shenanigans. In fact, fans often bond over their one-sided attachment to the same celebrity or toward tracking a broader group of celebrities.

Take Reddit, a site that allows users to form subreddit communities out of shared interest. Millions of Reddit users (real people) have cultivated community out of love for cultural icons, such as r/ElonMusk, r/TaylorSwift, and r/Kanye. To understand the scale of this ardent fandom, we can look at the subscriber counts for a sampling of these communities.

r/Entertainment (industry and celebrity gossip): 4,200,000 subscribers

r/PopCultureChat (celebrity gossip): 1,700,000 subscribers

r/ElonMusk: 1,600,000 subscribers

r/Fauxmoi (celebrity gossip): 1,200,000 subscribers

r/TaylorSwift: 906,000 subscribers

r/Kanye: 761,000 subscribers

r/Beyonce: 338,000 subscribers

r/JordanPeterson: 307,000 subscribers

These communities dwarf subscriber counts for subreddits of greater cosmic importance, like r/Climate (174k subscribers) and r/Racism (45k subscribers)—unless you’re willing to argue that tracking Kanye’s antics will positively impact climate change.

Does documenting the internet's preoccupation with celebrity gossip fully explain our despair over David Bowie or Prince's passing? No. Do these groups serve as tangible examples of our overzealous fascination with well-known actors and musicians (who will one day pass away)? Yes.

Need Help with a Data Project?

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data science and data journalism consulting services. Reach out if you’d like to learn more.

Email daniel@statsignificant.com

Final Thoughts: How Much Should We Mourn the Passing of a Famous Figure?

When a famous figure passes away, and our social media feeds erupt in dismay, it raises a series of moral questions about these online histrionics—should we mourn celebrities to such an extent?

Some take a critical view, arguing that our obsession with celebrity culture is an unhealthy distraction. Parasocial bonds with renowned figures, especially in the extreme, represent shallow means for building community and identity. From this view, society's fixation on famous deaths preoccupies us with spectacle, paradoxically distracting us from thinking about our own mortality. This critique may be harsh (and flat-out mean).

A less critical interpretation of this phenomenon stresses that many renowned figures have genuinely impacted our lives and culture. Far from distracting us, grieving accomplished people allows us to appreciate the contributions of those we've lost.

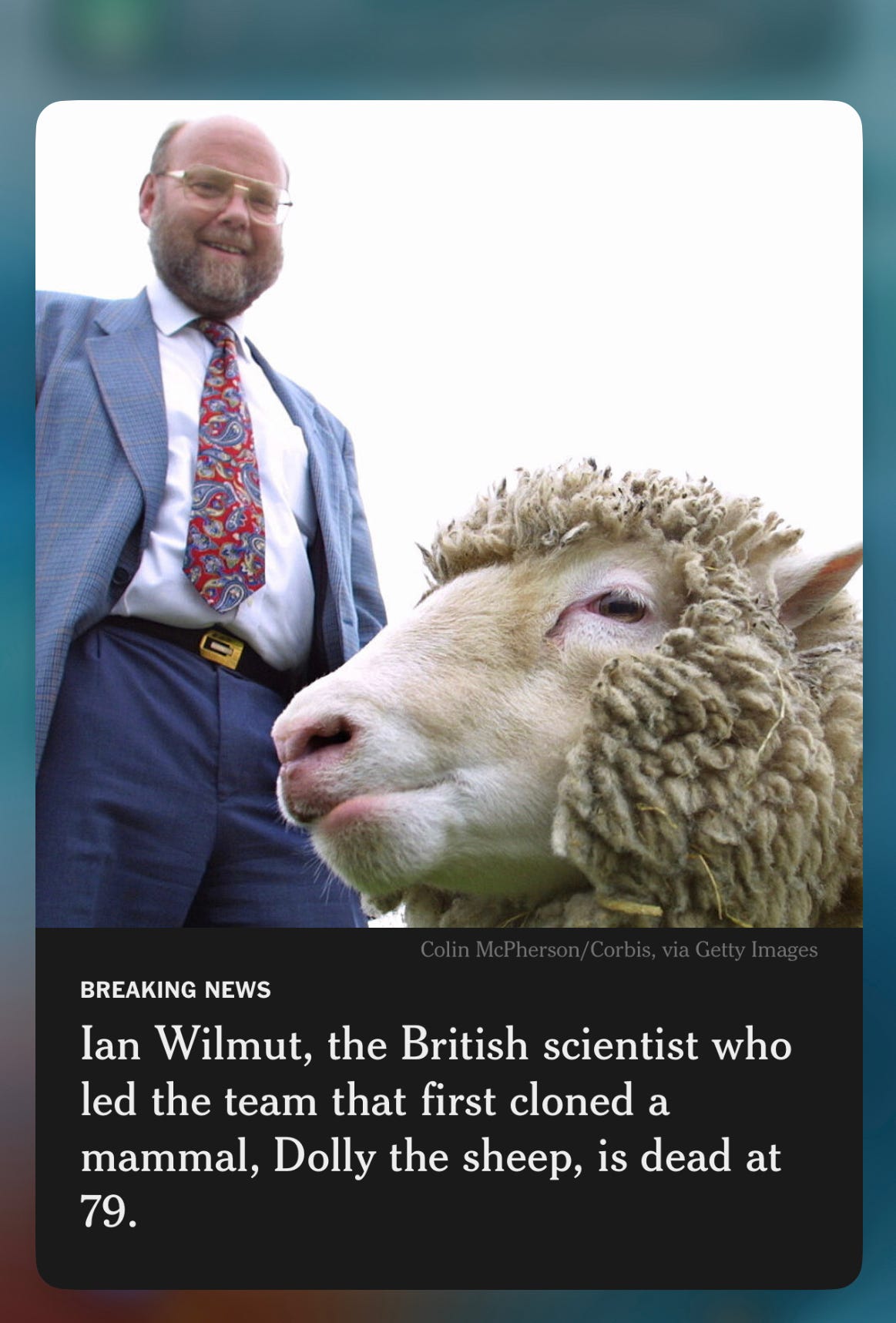

The other day, I received this push notification from the New York Times:

I scanned the notification and thought, "Why the hell am I reading this?" I knew nothing of Ian Wilmut before today; why do I have to stop what I'm doing to learn about this person? But, indeed, I stopped what I was doing, and I read Ian Wilmut's NYT obituary. Well, it turns out Wilmut was an incredible person, conjuring animal life from nothing—pioneering one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century. As usual, my knee-jerk cynicism was misplaced.

When a well-known person passes away, it reminds us to appreciate human achievements while simultaneously recognizing how short life is. Immediate responses in the media and on social platforms can be surface-level and sensational, but they also give us a chance to acknowledge that individual's impact on the world. At the end of the day, there's nothing wrong with celebrating each other's contributions.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

"Curated by a global team of six economists, this database covers millions of historical figures, using factors like Wikipedia page views, number of Wikipedia editions, and Wikipedia word counts to quantify renown."

As an editor, I always find these metrics *really* funny. A good friend of mine is currently going through making articles for all Alexander McQueen's collections -- all in-depth with great care and detail, going through Wikipedia's highest levels of peer review, which itself increases both page views and translations (editors on other projects prioritize quality-reviewed articles). She's writing the bad ones first, because they're easier.

I think you've nailed it, pre 1955 if you weren't a politician or an actor and maybe played football in Europe or South America it is hard to argue that the person was anything like what we would call famous now.

I also think the push alerts are a very interesting area. In the UK the BBC News App is used by around 12m each quarter (around one in four adults in the country) many of those have the push alerts on (Have never seen exact numbers) so the person(s) who choose the text for those alerts are probably the most influential journalists in the UK. How they choose to word a reaction to new inflation figures or the government's financial announcements has huge influence on how millions of people think about these subjects.